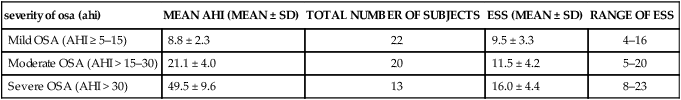

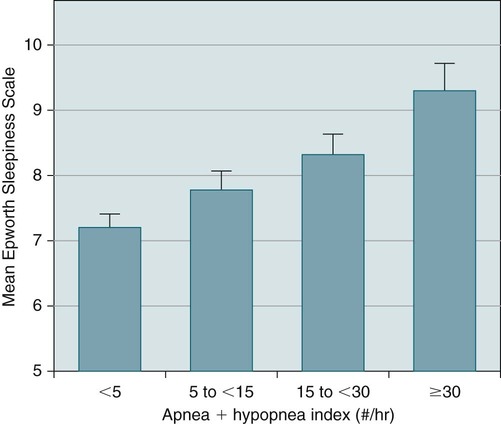

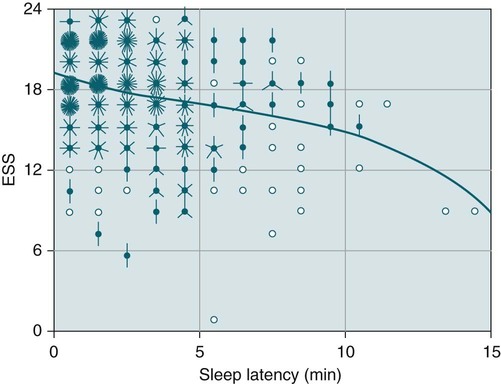

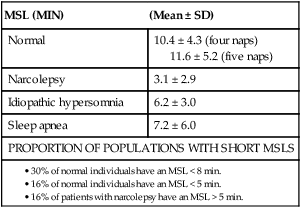

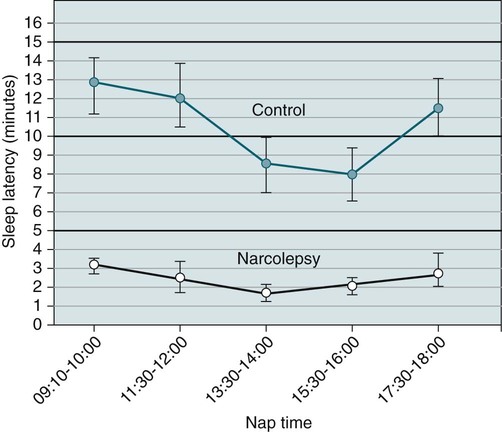

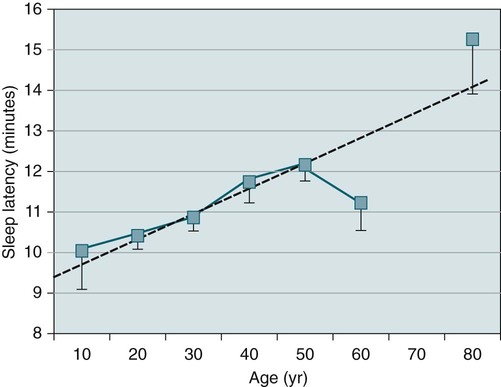

Chapter Points (see also Box 14–6) • The ESS measures self-rated average sleep propensity (chance of dozing) over eight common situations. The scale ranges from 0 to 24 with 10 or less being considered normal. • The MSLT objectively measures the tendency to fall asleep (MSL) and the propensity to have SOREMPs. • The MSLT consists of five naps spaced every 2 hours beginning about 1.5 to 3 hours after the wake-up time. • The MSLT should be preceded by a PSG to detect causes of sleepiness such as sleep apnea and to verify adequate sleep before the MSLT. MSLT findings are not considered reliable if less than 360 minutes of sleep is recorded. • The MSLT diagnostic criteria for narcolepsy include an MSL of 8 minutes or less and 2 or more SOREMPs. However, a negative MSLT does NOT rule out narcolepsy because the sensitivity of the MSLT for diagnosing narcolepsy is only approximately 70% to 80%. • The MSLT diagnostic criteria for idiopathic hypersomnia include an MSL of less than 8 minutes and 0 to 1 SOREMPs in five naps. • Up to 6% of untreated patients with OSA will have an MSLT meeting criteria for narcolepsy. • If narcolepsy in addition to OSA is suspected, patients should have a PSG on CPAP to document good treatment and adequate sleep and a subsequent MSLT on CPAP. This assumes that OSA has been well treated with CPAP for a period of time (e.g., documented CPAP adherence). • Medications that may affect MSLT sleep latency (stimulants, sedatives) or the number of SOREMPs (REM-suppressant medications) should be withdrawn for 10 days to 2 weeks preceding testing if possible. • The MWT objectively quantifies a patient’s ability to remain awake in a situation predisposing to sleep (dimly lighted room, sitting on a bed). The 40 minute MWT is recommended. Each MWT nap is terminated after 40 minutes if no sleep has been recorded; after 3 consecutive epochs of stage N1, or after a single epoch of any other sleep stage (N2, N3, or R). The sleep latency is defined as the time from lights out until the first epoch of any stage of sleep. Questionnaires such as the Stanford Sleepiness Scale or the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS)1,2 are measures of self-rated symptoms of sleepiness. The Stanford Sleepiness Scale (Table 14–1) measures subjective feelings of sleepiness (“fogginess, beginning to lose interest in staying awake”). A score above 3 is considered sleepy. In contrast, the ESS measures self-rated average sleep propensity (chance of dozing) over eight common situations that almost everyone encounters. The propensity to fall asleep is rated as 0, 1, 2, or 3 where 0 corresponds to never and 3 to a high chance of dozing (Table 14–2). The maximum score is 24 and normal is assumed to be 10 or less. ESS scores of 16 or greater are associated with severe sleepiness. TABLE 14–1 TABLE 14–2 The ESS correlates roughly with the severity of OSA (apnea-hypopnea index [AHI]) (Table 14–3)2,3 and improves (lower score) after continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment.4 However, as noted in Table 14–3, there is a wide range of ESS scores at any level of OSA severity. A large study by Gottlieb and coworkers3 found a modest correlation between the ESS and OSA severity in a large population-based study of 1824 subjects. The degree of daytime sleepiness in the population was relatively mild (Fig. 14–1). Johns2 reported a significant negative correlation between the ESS and the mean sleep latency (MSL) on the multiple sleep latency test (MSLT; an objective measure of sleepiness discussed in the next section) in a group of sleepy patients. However, Benbadis and colleagues5 found no correlation between the MSLT findings and the ESS. Sangal and associates6 found a statistically significant but low negative correlation between the ESS and the sleep latency (higher ESS associated with lower sleep latency) on the maintenance of wakefulness test (MWT) and MSLT in a large group of narcolepsy patients. A scatter plot of ESS versus sleep latency on the MSLT is shown in Figure 14–2. There was also a modest correlation between the sleep latencies as determined by the MSLT and MWT. Of interest, the correlation between the MSLT and the MWT latencies (r = 0.52, P < .001) was stronger than correlations between the ESS and the MWT or the MSLT latencies (r = –0.29, P < .001 and r = –0.27, P < .001, respectively).6 TABLE 14–3 Epworth Sleepiness Scale Scores in Mild, Moderate, and Severe Obstructive Sleep Apnea Adapted from Johns MW: A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: The Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep 1991;14:540–545. The MSLT7–12 is used to support a diagnosis of narcolepsy and/or quantify the degree of daytime sleepiness. The MSL (lights out to sleep onset) is a measure of the degree of daytime sleepiness. The sleep latency is the time from lights out to the beginning of the first epoch of any stage of sleep. The test is terminated if no sleep occurs within 20 minutes of lights out (maximum sleep latency is 20 min). After sleep onset, the MSLT continues for 15 minutes of clock time. If rapid eye movement (REM) sleep occurs within this time period, a sleep-onset rapid eye movement period (SOREMP) is said to have occurred. The MSLT criteria used to support a diagnosis of narcolepsy are an MSL of 8 minutes or less and 2 or more SOREMPs.13 Many factors can alter the findings of the MSLT and considerable clinical judgment is needed to avoid an error in interpretation. The MSLT may be used in the research setting as an objective measure of daytime sleepiness of a given population of interest or to assess a response to treatment. The clinical indications for the use of the MSLT (Box 14–1) are outlined by the current American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) practice parameters concerning the use of the MSLT10 and prior guidelines published by this organization.8,9 A standard-level recommendation states “the MSLT is a validated objective measure of the ability or tendency to fall asleep.” As mentioned previously, the sleep latency is the parameter that reflects the degree of daytime sleepiness. The MSLT is indicated for evaluation of patients with suspected narcolepsy or idiopathic hypersomnia, but NOT for evaluation of OSA patients before or after treatment, or to quantify sleepiness in patients with insomnia, medical, or neurologic disorders (other than narcolepsy). The practice parameters also outlined conditions under which a repeat MSLT is indicated. These include a prior MSLT with unusual conditions or if the initial MSLT was negative in a patient with a strong clinical suspicion of narcolepsy (see Box 14–1). A standardized MSLT protocol performed by an experienced sleep technologist (Boxes 14–2 and 14–3) is required to obtain accurate testing results. A four-nap MSLT is not reliable for the diagnosis of narcolepsy unless 2 SOREMPs have occurred after four naps. Even then, a five-nap MSLT is suggested because the physician reading the study may disagree with the technologist’s assessment of SOREMPs. A technologist experienced in performing the MSLT is essential.8–11 The technologist is required to accurately score sleep in real time. Of note, polysomnography (PSG) must precede the MSLT. This is required to rule out causes of sleepiness such as sleep apnea and to document an adequate amount of sleep preceding the MSLT. An adequate total sleep time during the PSG is needed for valid MSLT results. At least 360 minutes of sleep must be recorded for the MSLT findings to be reliable. A very high percentage of REM sleep (% of total sleep time) on the PSG should alert the physician to the possibility of REM rebound. This might be a clue to the recent withdrawal of a REM-suppressing medication or prior sleep deprivation. A sleep diary for 1 to 2 weeks before the MSLT may be helpful in documenting the adequacy of preceding sleep. Preceding sleep deprivation can result in shortened sleep latency.11,12 Some patients may need a total sleep time longer than 360 minutes during the PSG and during the weeks before the MSLT to normalize the MSL.12,14 A urine drug screen may help identify surreptitious medication use that can affect the MSLT results. Cigarette smoking should stop at least 30 minutes before each nap (Table 14–4). Vigorous physical activity should be avoided and any stimulating activity stopped at least 15 minutes before each nap. The patient should be asked whether she or he needs to use the bathroom before the nap is scheduled to begin. Between naps, the subject should be out of bed and observed in order to prevent sleep between the naps. A light breakfast was recommended at least one hour before the first nap and a light lunch immediately after the second nap. A typical MSLT schedule might include wake-up 6:00–7:00 am, breakfast, nap 1 at 9:00 am, nap 2 at 11:00 am, light lunch, nap 3 at 1:00 pm, nap 4 at 3:00 pm, nap 5 at 5:00 pm. TABLE 14–4 Multiple Sleep Latency Test Timetable: Before Testing MSLT = multiple sleep latency test; PSG = polysomnography; REM = rapid eye movement. Although not specifically addressed in the recent AASM practice parameters, it is usual practice to have patients change out of night clothes before nap testing begins. This was the recommendation in earlier published guidelines for the MSLT.8,9 As untreated OSA can be associated with MSLT findings consistent with narcolepsy,15 adequate treatment of sleep apnea (for a sufficient time period to allow for symptom improvement) should precede MSLT evaluation for narcolepsy. If narcolepsy is suspected in a patient being treated for sleep apnea (e.g., with CPAP or an oral appliance), PSG is usually performed on CPAP/oral appliance treatment. The PSG documents adequate treatment of sleep apnea and at least one night of adequate sleep before the MSLT. Although not addressed in the recent MSLT practice parameters, the 1992 AASM MSLT guidelines stated “To determine the concurrent presence of narcolepsy after treatment of the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome by CPAP, the MSLT should be performed with the patient using the CPAP device.” In this case, recording of machine flow is often performed in addition to electroencephalogram (EEG), electro-oculogram (EOG), chin electromyogram (EMG), and electrocardiogram (ECG). It is also worth mentioning that if unequivocal cataplexy is present in a patient with OSA, a diagnosis of concurrent narcolepsy can be made in the absence of confirmatory MSLT findings (see Chapter 24). Traditional gradations of the MSL considered a value less than 5 minutes to denote severe sleepiness and a value less than 10 minutes to denote pathologic sleepiness.8,9 A normal MSL was often stated to be greater than 15 minutes (10–15 was termed a gray zone). However, a recent large systematic review and meta-analysis of MSLT studies found the average MSL in normal individuals to be just above 10 minutes11 (Table 14–5), with many normal individuals having an MSL less than 10 minutes. TABLE 14–5 MSL = mean sleep latency; MSLT = multiple sleep latency test; SD = standard deviation. *MSLT MSL in normal and patient groups. Data from Littner MR, Kushida C, Wise M, et al: Practice parameters for clinical use of the multiple sleep latency test and the maintenance of wakefulness test. Sleep 2005;28:113–121; Arand D, Bonnet M, Hurwitz T, et al: A review by the MSLT and MWT Task Force of the Standards of Practice Committee of the AASM. The clinical use of the MSLT and MWT. Sleep 2005;28:123–144; and Aldrich MS, Chervin RD, Malow BA: Value of the multiple sleep latency test (MSLT) for the diagnosis of narcolepsy. Sleep 1997;20:620–629. The MSL values for studies of groups of patients with the major sleep disorders associated with daytime sleepiness published from a large analysis11 are listed in Table 14–5. Patients with narcolepsy had the shortest MSL. The sleep latency of patients with idiopathic hypersomnia and OSA is usually between 5 and 10 minutes. Of interest, up to 30% of normal populations have an MSL of 8 minutes or less. An MSL value of 8 minutes or less is part of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 2nd edition (ICSD-2) criteria for diagnosis of narcolepsy and less than 8 minutes for the diagnosis of idiopathic hypersomnia.13 Previously, a sleep latency of less than 5 minutes was the criterion.8,9,12 The ICSD-213 chose an MSL of 8 minutes rather than 5 minutes as a diagnostic criteria to improve the sensitivity of the MSLT for the diagnosis of narcolepsy.12 About 16% of narcoleptics have an MSL greater than 5 minutes and 16% of normal controls have an MSL below 5 minutes.11,13 A number of factors can affect the sleep latency during the MSLT (Box 14–4). The time of day of the nap affects the sleep latency. Of note, the shortest sleep latency tends to be in the third or fourth nap (early afternoon)7 (Fig. 14–3). The MSL for a five-nap MSLT is slightly higher than that for a four-nap MSLT. The sleep latency on the last nap is often the highest and may reflect anticipation of the end of the test (“anticipation of leaving the sleep center”). Interpretation of the MSLT can be problematic in shift workers or late sleepers. The MSL increases with increasing age (Fig. 14–4). The normative MSLT results for children are discussed in a later section. Medications (stimulants or sedatives) that could affect the MSL should be withdrawn 2 weeks before the MSLT if this is medically practical. Abrupt withdrawal before the study should also be avoided. The occurrence of REM sleep within 15 minutes of sleep onset (SOREMP) is more specific for the diagnosis of narcolepsy than an MSL of 8 minutes or less. Studies of normal populations have found 0 to 1 SOREMPs in five naps.7,11 However, SOREMPs can occur in normal individuals with prior sleep or REM sleep deprivation, in untreated OSA, and when there is a circadian phase delay (Box 14–5). Patients with depression or other psychiatric disorders can also have a short REM latency. In general, the number of MSLT SOREMPs increases as the sleep latency decreases.11 Those disorders associated with SOREMPs during the MSLT may also be associated with a short nocturnal REM latency.12 A recent review of the MSLT11 that analyzed available study data found that 2 or more SOREMPs were associated with a sensitivity of 0.78 and specificity of 0.93 for the diagnosis of narcolepsy. Aldrich and coworkers12 published their MSLT findings on a large number of patients with suspected narcolepsy (Table 14–6). If an initial MSLT was not diagnostic but narcolepsy was suspected clinically, repeat MSLT testing was performed. The study showed that patients with OSA can have a very short sleep latency and 2 or more SOREMPs (although the proportion of OSA patients is much lower compared with narcolepsy).12 In this study, about 63% of patients with sleep-related breathing disorders have an MSL less than 8 minutes whereas only 7% had 2 or more SOREMPs. The study also showed that a significant proportion of patients with a narcolepsy + cataplexy can have a negative MSLT. TABLE 14–6 Multiple Sleep Latency Test Findings in Patients Evaluated for Daytime Sleepiness

Subjective and Objective Measures of Daytime Sleepiness

Subjective Measures

DEGREE OF SLEEPINESS

SCALE RATING

Feeling active, vital, alert, or wide awake

1

Functioning at high levels, but not at peak; able to concentrate

2

Awake, but relaxed; responsive but not fully alert

3

Somewhat foggy, let down

4

Foggy; losing interest in remaining awake; slowed down

5

Sleepy, woozy, fighting sleep; prefer to lie down

6

No longer fighting sleep, sleep onset soon; having dreamlike thoughts

7

Asleep

X

SITUATION: “USUAL WAY OF LIFE IN RECENT TIMES”

CHANCE OF DOZING SCORE 0, 1, 2, 3*

Sitting and reading

0–3

Watching TV

0–3

Sitting, inactive in a public place (e.g., a theater or a meeting)

0–3

As a passenger in a car for an hour without a break

0–3

Lying down to rest in the afternoon when circumstances permit

0–3

Sitting talking to someone

0–3

Sitting quietly after a lunch without alcohol

0–3

In a car, while stopped for a few minutes in traffic

0–3

Total

0–24

*0 = would NEVER doze

1 = SLIGHT chance of dozing

2 = MODERATE chance of dozing

3 = HIGH chance of dozing

0–10 normal

severity of osa (ahi)

MEAN AHI (MEAN ± SD)

TOTAL NUMBER OF SUBJECTS

ESS (MEAN ± SD)

RANGE OF ESS

Mild OSA (AHI ≥ 5–15)

8.8 ± 2.3

22

9.5 ± 3.3

4–16

Moderate OSA (AHI > 15–30)

21.1 ± 4.0

20

11.5 ± 4.2

5–20

Severe OSA (AHI > 30)

49.5 ± 9.6

13

16.0 ± 4.4

8–23

Objective Measures

Multiple Sleep Latency Test

MSLT Protocol

–2 weeks

Stop REM suppressing medications, stimulants, and stimulant-like medications.

–(1–2 wk)

Keep sleep diary and obtain adequate sleep and regular routine.

–1 day

PSG during regular sleep period precedes MSLT.

–30 min

Stop tobacco smoking.

–15 min

Stop stimulating activity.

–10 min

Comfortable clothing, visit restroom if needed.

–5 min

Calibration series.

–30 sec

Assume comfortable position for sleep.

–5 sec

“Please lie quietly, assume a comfortable position, keep your eyes closed and try to fall asleep.”

0 sec

Lights out

Other MSLT Considerations

MSL Values in Normal Populations and Patients

MSL (MIN)

(Mean ± SD)

Normal

10.4 ± 4.3 (four naps)

11.6 ± 5.2 (five naps)

Narcolepsy

3.1 ± 2.9

Idiopathic hypersomnia

6.2 ± 3.0

Sleep apnea

7.2 ± 6.0

PROPORTION OF POPULATIONS WITH SHORT MSLS

Factors Affecting the MSLT MSL

Number of SOREMPs

Utility of the MSLT for Diagnosis of Narcolepsy

NARCOLEPSY WITH CATAPLEXY

NARCOLEPSY WITHOUT

CATAPLEXY*

SLEEP-RELATED BREATHING DISORDER

N

106

64

1251

MSL < 5 min

87%

81%

39%

MSL < 8 min

93%

97%

63%

≥2 SOREMPs

74%

91%

7%

≥2 SOREMPs +

MSL < 5 min

67%

75%

4%

≥ 2 SOREMPs +

MSL < 8 min

71%

91%

6%

SOREMP on PSG

33%

24%

1% ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Subjective and Objective Measures of Daytime Sleepiness