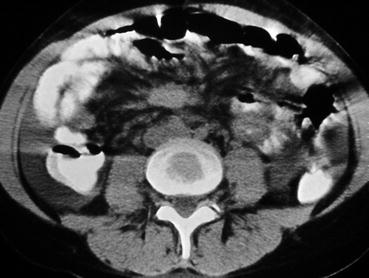

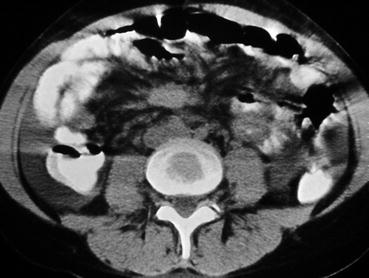

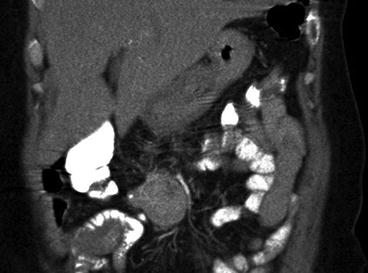

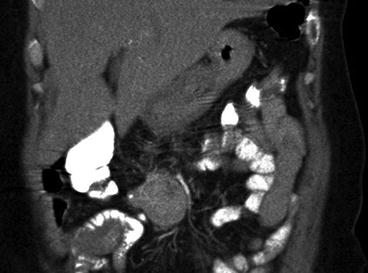

Fig. 25.1

Sporadic, solitary gastric NET with lymph node metastasis removed by gastric resection (From Åkerstrom et al. [12])

Two thirds of type 3 tumours have infiltrated the muscularis layer and 50 % have invaded all layers of the gastric wall. Regional lymph node metastases may be present in 20–50 %, also with small tumours, and liver metastases eventually develop in two thirds of the patients [12, 24]. The sporadic gastric NETs can have atypical histology, with pleomorphism, high mitosis rate and high Ki-67 index. The atypical tumours are larger, with mean size around 5 cm, more frequently invasive and have unfavourable survival [12].

25.5.2.4 Atypical Carcinoid Syndrome

The ECL cells have the ability to secrete histamine and disseminated lesions of type 3 gastric NETs may in 5–10 % be associated with an “atypical carcinoid syndrome”. The syndrome can occur also in exceptional patients with disseminated type 1 and 2 tumours [12]. The syndrome has a patchy “geographic” flush, urticarial rash, cutaneous oedema, mucous membrane swelling, bronchospasm, salivary gland swelling and lacrimation. Since the syndrome is caused by histamine release from tumour cells, urinary estimates of the histamine metabolite methylmidazole-acetic acid (MelmAA) serve as tumour marker. Most gastric NETs lack the enzyme L-amino acid decarboxylase and few patients have elevated serotonin levels. Due to this decarboxylation defect, the patients will have only minimal elevation of urinary 5-HIAA values [12].

25.5.2.5 Diagnosis

Diagnosis of CAG-related type 1 NETs is based on demonstration of high serum gastrin levels, lack of gastric acid secretion with high pH in gastric aspirate (pH >3 in the gastric aspirate excludes ZES) and confirmation of mucosal atrophy together with ECL cell hyperplasia in endoscopic biopsies from the antrum (two biopsies) and fundus (four biopsies) [12]. Basal and pentagastrin-stimulated gastric acid secretion studies are recommended. Endoscopy is used to evaluate multiplicity and size of the gastric NETs. Tumour biopsies should be stained with endocrine tumour markers (CgA, synaptophysin and VMAT2) and proliferation markers (Ki-67 index) [12]. Multiple NETs in the gastric fundus in an elderly are most likely to represent CAG-associated NETs.

Diagnosis of MEN1-associated type 2 gastric NETs and ZES is based on demonstration of low gastric pH and raised basal acid output in gastric acid secretion studies, generally together with markedly raised gastrin levels [12]. Serum gastrin >1,000 pg/m is diagnostic of ZES if gastric pH is <2. In other patients a secretin test may be required and is diagnostic with paradoxical rise in gastrin, 200 pg/mL over baseline, but 15 % of patients have negative secretin test. The important differential diagnosis is CAG, where patients have high gastrin, without gastric acid (with high gastric pH, pH >3 excludes ZES). Biochemical screening for other MEN1 endocrinopathies includes measurements of serum calcium and parathyroid hormone, pituitary hormones (prolactin and insulin-like growth factor 1, IGF-1), pancreatic hormones and CgA [12]. MEN1 genetic testing is done if the familial disease is not previously recognised.

Diagnosis of the type 3 gastric NETs is essentially settled by the features and by verifying absence of hypergastrinaemia.

Radiology is generally not needed in type 1 gastric NETs without signs of spread. CT with contrast enhancement (3-phase), SRS and PET studies (increasingly 68Ga-DOTATOC/PET/CT) are used to determine metastatic spread in type 2 and 3 NETs [12]. For type 3 lesions with higher proliferation, FDG PET may be of value. EUS should be added to the endoscopic examination in type 1 and 2 lesions larger than 1 cm and all type 3 lesions to provide information about invasion and the depth and may reveal regional lymph node metastases (and possibly pancreaticoduodenal lesions in MEN1 patients) [12, 22].

25.5.2.6 Surgical Treatment

Type 1 gastric NETs <1 cm are generally indolent and can be followed with yearly endoscopic surveillance [10, 12, 22–24]. Tumours >1 cm or multiple lesions without invasion can be treated with endoscopic mucosal resection or multiple band mucosectomy [10, 25]. Few large invasive tumours require local surgical excision, and only rare larger, multifocal lesions need gastric resection [11, 23, 24]. Antrectomy combined with tumour excision may be considered in type 1 cases with invasion and repeated recurrence, but the effect on remaining clinically significant lesions may be limited [23]. Treatment with somatostatin analogues has been associated with time-limited regression of type 1 lesions, but disease progression has been noted at follow-up 5 years after termination of therapy [10, 26–29].

Surgical treatment in type 2 gastric NETs is focused on removing the source of hypergastrinaemia, generally by excision of duodenal gastrinomas via duodenotomy, together with clearance of lymph node metastases (see below) [22, 24, 26]. The type 2 gastric NETs per se require endoscopic or surgical excision that should be radical. Gastric resection or gastrectomy combined with regional lymph node clearance is recommended for larger and multifocal tumours or those with deep gastric wall invasion or angioinvasion [22, 24]. If hypergastrinaemia has not been reversed by surgery for gastrinoma, somatostatin analogue treatment may be used to reduce tumour growth, especially in cases with multiple gastric NETs, though proton-pump inhibitors are the most often suggested therapy [26, 30–32].

Type 3 sporadic gastric carcinoids should be radically treated with gastric resection and regional lymph node clearance. Tumours larger than 2 cm and those with atypical histology or gastric wall invasion are most appropriately treated with gastrectomy [12, 23, 24]. Endoscopic resection is only occasionally performed for small non-metastasised tumours [10, 12]. The overall 5-year survival for patients with type 3 lesions has been ~50 %, but only 10 % in cases with distant metastases [10, 12].

25.5.2.7 Gastrinoma

Tumours with sparse staining for gastrin may occur in association with CAG. Tumours with intense staining for gastrin are rare in the stomach and have been located in the pre-pyloric mucosa close to the duodenum. Few gastric NETs have caused hypergastrinaemia and peptic ulcer disease, but they still represent an exceptional but possible origin of gastrin excess and ZES [12]. Rare tumours may present with ectopic Cushing’s syndrome due to ACTH secretion [12].

25.5.3 Duodenal NETs

NETs of the duodenum are rare and comprise less than 2 % of all GEP-NETs [12, 22]. Duodenal adenomas or adenocarcinomas are more frequent. Duodenal NETs comprise gastrinomas (48 %) (not described here; see Chap. 6), somatostatinomas (44 %), non-functioning tumours, staining for serotonin (28 %) or calcitonin (9 %) and rare gangliocytic paragangliomas or carcinomas [22, 33, 34]. The duodenal NETs generally present in the sixth decade of life. The majority (>90 %) occurs in the first and second part of the duodenum and 20 % in the periampullary region. The tumours are characteristically small (<1.5 cm); most are T1, but lymph node metastases has been reported to occur in around 50 % and liver metastases in <10 %.

25.5.3.1 Somatostatin-Rich NETs

NETs with somatostatin reactivity occur in the ampullary or periampullary region, almost exclusively in the ampulla of Vater, causing obstructive jaundice, pancreatitis or bleeding [22, 34, 35]. A clinical somatostatinoma syndrome is very rare. The tumours appear as 1–2 cm homogeneous ampulla nodules, which only occasionally are polypoid, larger or ulcerated. Regional lymph node or liver metastases are present in nearly 50 % of patients. Unlike conventional NETs, the tumours have a glandular growth pattern and may characteristically contain special laminated psammoma bodies. The lesions are often associated with von Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis (neurofibromatosis type 1, NF1) and occasionally with pheochromocytoma [22, 34, 35]. The ampullary somatostatin-rich NETs may be locally excised, together with clearance of regional lymph glands, but since there is no established correlation between tumour size and metastases, pancreaticoduodenectomy has been recommended in younger patients [32].

25.5.3.2 Gangliocytic Paragangliomas

Gangliocytic paragangliomas are rare tumours, occurring almost exclusively in the second portion of the duodenum, and are sometimes associated with NF1 [33]. The tumours consist of a mixture of paraganglioma, ganglioneuroma and NET tissue, with reactivity for somatostatin and pancreatic polypeptide (PP). The tumours may be recognised incidentally or because of bleeding. They may be large but are generally benign and often have an excellent prognosis following surgical excision [33].

25.5.3.3 Other Duodenal NETs

More unusual WDNETs have reactivity for other hormones, such as calcitonin, PP and serotonin [12, 22, 33, 36, 37]. Most of these tumours occur as small polyps (<2 cm) in the proximal duodenum. Multiple tumours should raise suspicion of an associated MEN 1 syndrome. The majority are low-grade malignant and often suitable for endoscopic mucosal resection or local surgical excision, only rare large tumours require pancreaticoduodenectomy [33, 36, 37].

A distinct group of duodenal NETs without release or staining for hormones is also recognised. These tumours have a somewhat different biology and have less often metastasised than the gastrinomas and somatostatinomas [22, 33, 36, 37]. Some are asymptomatic and incidentally found at endoscopy, others present with non-specific abdominal symptoms, gastrointestinal bleeding and sometimes vomiting or weight loss. Most tumours are located in the first portion of the duodenum, occasionally in the second part and rarely in the third portion (horizontal duodenum). The majority stains for CgA and some for synaptophysin and/or NSE [36, 37]. Up to one-third of the patients have had other primary malignancies as well, including adenocarcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract, prostate or other organs [36, 37]. More than half of the tumours are smaller than 2 cm and generally have a good prognosis after resection. Lesions smaller than 1 cm can be endoscopically excised, but re-examination with follow-up endoscopy is required to ensure complete removal. Size >2 cm, invasion beyond the submucosa and presence of mitotic figures are independent risk factors for metastases (grade 2 tumours). Tumours with these risk factors are likely to recur also after apparently curative surgery, even if no lymph node metastases have been detected, whereas lesions smaller than 2 cm rarely metastasise [36, 37]. Rare duodenal tumours may cause an ectopic Cushing’s syndrome due to ACTH secretion [33].

The treatment suggested for larger tumours is segmental duodenal resection or pancreaticoduodenectomy in order to decrease the risk of recurrence [36, 37]. Periampullary tumours behave in malignant fashion and need more radical surgery. Patients with metastasising duodenal NETs may survive for decades, substantiating that NETs are less aggressive than adenocarcinomas.

25.5.3.4 Poorly Differentiated Duodenal Neuroendocrine Carcinomas (PDNECs)

PDNECs (large or small cell) in the duodenum are exceptionally rare, occurring most often in the ampulla of Vater, and the patients present with obstructive jaundice and invariably with a rapidly fatal course [36, 37].

(For excellent review including endoscopic management of gastroduodenal NETs, see [22]).

25.5.4 Pancreatic NETs

(Pancreatic islet cell tumours are reported in Chap. X). Exceptional PNET stain intensely for serotonin (and may also contain other biogenic amines) [12, 38]. They appear histologically as classical GEP-NETs, but few have been associated with the carcinoid syndrome. The tumours are managed surgically according to guidelines similar to those for non-functioning malignant pancreatic NETs. Hepatic metastases and a carcinoid syndrome may be treated with somatostatin analogues and interferon or with chemotherapy in the presence of higher proliferation rate [38].

25.5.5 Jejunoileal Small Intestinal (Si-NETs)

The jejunoileal small intestinal NETs (Si-NETs), also named “classical” midgut carcinoids, originate from intestinal enterochromaffin (EC) cells in intestinal crypts and can be recognised by typical tumour cell serotonin immunoreactivity. Carcinoids may be detected in up to 1/150 of routine autopsies, indicating that the tumours may remain silent throughout life [39, 40]. The Si-NETs account for 25 % of small bowel neoplasms and have been diagnosed with slight male predominance at a mean age of 65 years.

The primary Si-NETs occur most often in the distal ileum, within 60–80 cm of the ileocaecal valve, less often in the proximal ileum or the jejunum. Occasional tumours in the caecum with serotonin immunoreactivity are classified as Si-NETs [21, 41, 42]. The primary tumour is typically a small, flat and fibrotic submucosal lesion; occasional tumours may be polypoid and fungating [43]. The tumours may be difficult to detect at surgery, often appearing only as a localised fibrosis or thickening of the intestinal wall (Fig. 25.2a), but may even with minimal fibrosis cause intestinal obstruction (Fig. 25.2b) [43]. In an own series more than 30 % of patients subjected to surgery were found to have multiple, submucosal tumour nodules in the small intestinal wall close to the primary tumour, likely to represent local lymphatic spread [43, 44]. Rare cases have had additional larger polyps in the proximal intestine, possibly representing additional primary tumours [43, 44]. Mesenteric metastases occur in high frequency, irrespective of tumour size, and microscopic spread has been almost invariably present [43]. When growing close to the intestinal wall, the metastases may be easily mistaken to represent primary tumours, and some primaries have extended directly into node metastases [43, 45]. The mesenteric metastases have often grown larger than the primary tumour and evoked a desmoplastic reaction with a typical pronounced mesenteric fibrosis (Fig. 25.3). The fibrosis may be due to local effects of serotonin, growth factors and other substances released from the Si-NET metastases [12, 45–47].

Fig. 25.2

(a) Si-NET primary tumour visible as a localised fibrotic thickening of the intestinal wall; (b) Si-NET primary tumour with minimal fibrosis causing partial intestinal obstruction

Fig. 25.3

CT image of a mesenteric metastasis from a Si-NET surrounded by fibrosis (appearing like a “hurricane centre”) (From Åkerström et al. [45])

Larger metastases and more extensive fibrosis have sometimes caused mesentery contraction and tethered the mesenteric root to the retroperitoneum, with fibrous binding to the horizontal duodenum [43, 45]. The mesenteric tumours may extend high in the mesenteric root and may sometimes grow into the duodenal wall or into the pancreas or spread to the hepatoduodenal ligament or to the retroperitoneum/and para-aortal spaces [42, 43, 45, 48]. The fibrotic adhesions may kink and entrap the intestines and cause partial or complete small bowel obstruction and at advanced stage occasionally duodenal obstruction [43, 45, 48]. With extended mesenteric tumour growth and fibrosis, mesenteric vessels may be encased, and intestinal segments of variable length will appear blue-reddish due to incipient venous ischaemia (Fig. 25.4). The patient may experience diarrhoea or functional obstruction and occasionally abdominal angina [12, 43, 45, 48, 49]. A specific angiopathy, named vascular elastosis, with elastic tissue proliferation in the adventitia and marked thickening of mesenteric vessel walls has been reported with advanced Si-NETs [50], though in our experience tumour compression and fibrosis has been the obvious cause of intestinal ischaemia [43, 45].

Fig. 25.4

Limited intestinal segment with venous ischaemia due to Si-NET mesenteric tumour (From Åkerström et al. [45])

Cases with higher mesenteric root tumours and central mesenteric vein or artery occlusion may have longer involved intestinal segments with blue pale cyanosis or occasionally absent arterial circulation (Fig. 25.5). Rare patients with occlusion of a larger mesenteric vein branch may experience a WDHA syndrome-like condition, severe watery diarrhoea, malnutrition and emaciation [51, 52]. If the tumour and fibrosis have remained for longer time, bowel adhesions and kinking have often created a conglomerate of intestinal loops fixed to the abdominal walls, which sometimes need to be removed en bloc [12, 43, 45]. The incidence of mesenteric metastases at time of diagnosis has been 36–39 % in reports based on imaging studies [53].

Fig. 25.5

Longer ischaemic intestinal segment with compromised mesenteric vein and artery circulation, due to a high Si-NET mesenteric tumour

In the recent own large series of Si-NET patients, 93 % of operated patients had mesenteric metastases at operation [42]. Distant metastases in retroperitoneal/para-aortal location or more occasionally in the hepatoduodenal ligament were identified in 18 % of patients. Liver metastases were present at diagnosis or discovered at operation in 61 % of patients and occurred during follow-up in an additional 16 % [42]. The majority of patients had bilateral and multiple liver metastases; around 14 % had fewer than five metastases in one liver lobe; occasional metastases were dominant with conspicuous growth [42]. Around 10 % of patients presented with liver metastases without identified mesenteric lesions. Peritoneal carcinomatosis was revealed in 20 % of operated patients, ovarian metastases in 4 % and pancreatic or splenic metastases each occurred in 0.5 % [42]. Extra-abdominal spread to lymph nodes occurred at diagnosis in 4.0 % and to other sites in 6.1 % including bone, breast and skin [42]. Many patients had multiple sites of extra-abdominal spread, most often to mediastinal and peripheral lymph nodes (including neck lymph glands, which occasionally was the first presentation) and bone [42]. During follow-up of our patient series, another 12 % developed extra-abdominal spread [42]. Especially bone metastases have been previously associated with poor prognosis [41, 54].

25.5.5.1 Clinical Symptoms

Many patients with Si-NETs have experienced long periods of unspecific episodic abdominal pain and diarrhoea, often misinterpreted as irritable bowel syndrome or food allergy before the disease has been clinically diagnosed [10, 43, 45, 55]. Others have had unrecognised features of the carcinoid syndrome with discrete flush misinterpreted as menopausal complaints or palpitations and intolerance for specific food or alcohol [10, 43, 45, 56]. Intestinal bleeding has generally been rare with Si-NETs due to the submucosal location of the primary tumour and has been more likely to occur with more rare, larger, polypoid, fungating primary tumours [43, 45]. Bleeding may also occur when mesenteric metastases have grown into the horizontal duodenum or in the presence of intestinal venous stasis and incipient ischaemia [12, 43, 45]. Intermittent pain attacks have been common and often increased in frequency until the patient has developed subacute or acute intestinal obstruction requiring surgery. In around 50 % of patients, the Si-NET diagnosis has become evident after needle biopsy of liver metastases [12, 43, 45].

25.5.5.2 Carcinoid Syndrome

The carcinoid syndrome, described in 1954 by Thorson, has been reported to occur in approximately 20 % of patients with jejunoileal NETs, though the frequency may be higher at referral centres [12, 40–43, 53]. The syndrome includes flushing, diarrhoea, right-sided heart valve disease and bronchoconstriction. Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine), derived from the amino acid tryptophan, has been identified as the major cause of the syndrome [10, 41, 45]. Serotonin is inactivated by monoamine oxidase in the liver and in the kidney converted to 5-HIAA, which is excreted in the urine. Presence of the carcinoid syndrome generally implies that the patient has liver metastases, with secretion directly into the systemic circulation [12, 41, 45]. Occasionally the syndrome may occur in patients with large retroperitoneal or ovarian lesions, where the secretion exceeds the capacity of the monoamine detoxification or can bypass the liver and drain directly into the systemic circulation [12, 41, 45]. The syndrome is related to release also of other vasoactive factors tachykinins (substance P, neuropeptide K), prostaglandins and occasionally norepinephrine [12, 45, 57].

Secretory diarrhoea is the most common feature of the syndrome (reported in around 70 %), but may initially be mild and unspecific. Diarrhoea tends to be most prevalent in the morning and is often meal related. The diarrhoea may have other causes in NET patients, especially when previously operated upon or having advanced disease [12, 40, 45]. The commonly performed distal small intestinal resection leads to reduced bile salt absorption; treatment with bile acid-binding agents (cholestyramine) may provide relief. Somatostatin analogues in high doses may cause malabsorption diarrhoea, with foamy, floating diarrhoea after meals, which can be treated with pancreatic enzymes (Creon). Patients with long-standing poorly controlled carcinoid syndrome may develop niacin deficiency and pellagra (a syndrome with diarrhoea, dementia and dermatitis), which can be prevented by niacin supplementation. Other causes are a short bowel after surgery and partial intestinal obstruction. In patients with the large mesenteric tumours, intestinal venous stasis or ischaemia may contribute significantly to stool frequency. Occlusion of main mesenteric vein branches may cause severe watery diarrhoea and malnutrition, due to severely oedematous, fluid-leaking intestinal segments [12, 41, 45, 51, 52].

Cutaneous flushing (reported in around 65 %) affects the face, neck and upper chest and is the most characteristic feature of the carcinoid syndrome [12, 41, 45, 56]. Flushing may nevertheless easily be overlooked, especially in females at menopause. The flush may be provoked by stress, alcohol, certain food, aged cheese or coffee. It is often of short duration, lasting for 1–5 min, but may occasionally be prolonged for hours or even days. Flushing may occasionally be severe and long-standing, and with chronic flush, the patients may develop telangiectasies and persistent blue-cyanotic discolouration of the skin on the nose and chins.

Heart valve fibrosis, with plaque-like fibrotic endocardial thickening, affects the tricuspid and pulmonary valves, as a late consequence of a severe and long-standing carcinoid syndrome and high serotonin levels [12, 41, 45, 58–60]. This will cause retraction and fixation of the heart valves and subsequently regurgitation and stenosis, leading to tricuspid regurgitation and pulmonary valve stenosis. Tricuspid valve abnormalities was in one series reported in 65 % of patients with the carcinoid syndrome, and 19 % had pulmonary valve stenosis [60]. In less than 10 % the fibrosis may involve also the left-sided heart valves, in case of a patent oval foramen or when the pulmonary monoamine oxidase activity is exceeded, and then possibly contribute to bronchoconstriction.

The carcinoid heart disease may lead to progressive right-sided heart failure and severe lethargy and used to be the cause of death in 50 % of patients with the carcinoid syndrome [12, 40, 48, 58–60]. Nowadays, after introduction of somatostatin analogues, patients more often die from progressive tumour disease. Affected patients may require heart surgery and prostheses replacement of fibrotic heart valves [59, 60]. The operation may lead to substantial improvement, but can especially in older persons be associated with complications [60]. The heart disease is efficiently diagnosed by echocardiography, which should invariably be performed prior to major abdominal surgery.

Bronchial constriction as part of the carcinoid syndrome caused by small intestinal NETs is relatively rare, but may occur during anaesthesia.

25.5.5.3 Imaging

The primary Si- NETs generally escape detection by conventional bowel contrast studies because of limited size [10, 12, 21, 61]. Typical arcading of entrapped intestines, with segments of partial obstruction, may be revealed with advanced disease and occasionally the signs of chronic obstruction, with dilatation, and oedematous thickened bowel wall. In the presence of large bowel symptoms, entrapment of the sigmoid or transverse colon may be important to identify prior to surgery. Concomitant colorectal adenocarcinoma has been reported, and it may be necessary to exclude coexisting recto-sigmoidal adenocarcinoma by endoscopy, prior to surgery or during follow-up of Si-NETs.

CT can rarely visualise a primary Si-NET, but will often reveal mesenteric lymph node metastases, retroperitoneal extension of such masses and liver metastases. The presence of a circumscribed mesenteric mass with radiating densities is highly suspicious for an Si-NET mesenteric metastasis. Dynamic CT with contrast enhancement is important prior to operation, by possibility to reveal relation between the mesenteric metastases and the main mesenteric vessels [12, 45]. In cases with intestinal ischaemia, CT may show a characteristic image of dilated peripheral veins (Fig. 25.6) and oedematous loops of intestine. CT with contrast enhancement is often the primary method for visualisation of liver metastases, but fails to identify the smallest lesions. MRI can sometimes be more efficient than CT for demonstration of liver metastases. Percutaneous US with power Doppler enhancement, and use of US contrast, may increase sensitivity for the detection of liver metastases and is mainly used to visualise liver metastases and to guide fine or semi-fine-needle biopsy of the liver or mesenteric metastases for histological diagnosis and grading.

Fig. 25.6

CT image of Si-NET case with intestinal ischaemia showing mesenteric tumour surrounded by dilated peripheral mesenteric veins

OctreoScan®

In nearly 90 % of cases, Si-NETs express somatostatin receptor types 2 and 5, for which the somatostatin analogue octreotide has high affinity [12, 21, 45]. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy, SRS (OctreoScan®), has detected Si-NETs with a sensitivity of 90 % and has been commonly utilised to determine metastatic spread. OctreoScan® is especially efficient for detection of extra-abdominal spread and can visualise bone metastases better than isotope bone scan, which may miss osteolytic metastases.

Positron Emission Tomography (PET)

PET with the serotonin precursor 5-hydroxytryptophan, labelled with 11C (5HTP-PET), or gallium-68 (68Ga) PET can identify the Si-NETs with the highest sensitivity and has been increasingly used to diagnose stage and monitor effects of therapy [12, 17–19, 45, 62]. 68Ga-DOTATOC/PET/CT has revealed additional hepatic or extrahepatic metastases in more than 60 % of patient planned for liver resection or liver transplantation, which strongly impacted treatment decisions based on CT and/or MRI investigations that had failed to reveal these additional metastases [19]. FDG-PET imaging may be used to detect intermediate and high-grade poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (PDNECs) (sensitivity of 92 % with Ki-67 >15 %), but will not visualise low-grade well-differentiated lesions [20].

25.5.5.4 Diagnosis

Needle biopsy specimens from metastases are often used for diagnosis. The NET cells stain immunocytochemically with neuroendocrine tumour markers, mainly CgA and synaptophysin, and reactivity with serotonin-specific antisera implies that a primary tumour should be searched for in the midgut [12, 21, 45]. Most jejunoileal NETs show a mixed insular and glandular growth pattern; occasional tumours have a pure insular and trabecular pattern and have been reported to have slightly less favourable prognosis [12, 21]. Proliferation rate determined with the Ki-67/MIB antibody has often been very low <2 % in classical Si-NETs. Occasional tumours have higher proliferation rate (grade 2) or may change to higher grade during the disease course [12, 21]. Very rare lesions present as PDNEC with poorly differentiated pattern and high proliferation rate with poor prognosis and sparse effects of surgery.

25.5.5.5 Surgery

Since Si-NETs patients may be subjected to acute laparotomy due to abdominal pain or intestinal obstruction with unknown diagnosis, it is important that surgeons in general learn that the Si-NETs are common small bowel neoplasms and also come to recognise the typical features of a small ileal tumour and conspicuously larger mesenteric metastases with surrounding fibrosis [12, 43, 45, 48, 49, 63, 64]. Since an intestinal bypass may complicate more radical surgery, the locoregional tumour should if possible be removed by mesenteric wedge resection and intestinal resection, with clearance of lymph node metastases around the mesenteric artery and vein branches [12, 49]. The procedure is generally justified also in patients with moderately spread liver metastases. If the surgery has been inadequately performed, reoperation for removal of a remaining mesenteric tumour may be considered, as the patient may otherwise risk future abdominal complications [12, 43, 45, 48, 49, 63]. If grossly radical locoregional tumour removal has been accomplished, the Si-NETs patients often remain symptom-free for long periods from treatment with somatostatin analogues and interferon (IFN-α). However, the Si-NETs are markedly tenacious and recurrence with liver metastases should be expected in the vast majority of patients (60–80 %) if follow-up is long enough [43, 45, 48, 49, 63]. Since the Si-NETs are slow-growing tumours, clinically overt recurrence may occur after long duration of up to 10–25 years [45, 49, 63]. Earlier recurrence may be diagnosed by serum CgA estimates, rather than the urinary 5-HIAA measurements.

Many Si-NETs patients present with liver metastases and sometimes also features of the carcinoid syndrome. Life expectancy used to be poor in patients with liver metastases and the carcinoid syndrome; now symptoms may be efficiently controlled with somatostatin analogues and IFN-α, which together with other new treatment modalities have markedly increased life expectancy and life quality [21, 45, 49, 63]. The carcinoid heart disease used to be a principal death cause in Si-NETs patients, together with abdominal complications, which played a significant role in 40 % of patients [12, 63]. Possibly due to treatment with efficient biotherapy, the heart disease has become less common, and a majority of patients now die with spread malignancy or liver failure after an extended disease course [41, 61, 63]. Improved survival by somatostatin analogue treatment documented by the PROMID study has widened indications for locoregional tumour removal in patients with advanced Si-NETs [41, 63–65]. Because partial intestinal obstruction or incipient intestinal ischemia may cause similar symptoms of feeding-related abdominal pain, laparotomy can be needed to distinguish these causes.

Abdominal pain is unlikely to be caused merely by the carcinoid syndrome, and complications of the mesenteric tumour are important to recognise since considerable long-term palliation may be achieved by appropriate surgery [63, 64]. Not all mesenteric metastases will cause extensive fibrosis, and the course of the mesenterico-intestinal disease can be variable, but elective surgery at an early stage may allow removal of the mesenteric tumours with more limited intestinal resection before involvement of major mesenteric vessels becomes too extensive [12, 63, 64]. The authors advocate removal of the mesenterico-intestinal tumour also in asymptomatic patients and suggest liberal surgical consultations when abdominal symptoms occur during periods of medical treatment [63]. Too late surgical consultation may allow the disease to be increasingly difficult or impossible to manage surgically.

25.5.5.6 Surgical Technique for Removal of Mesenteric Metastases

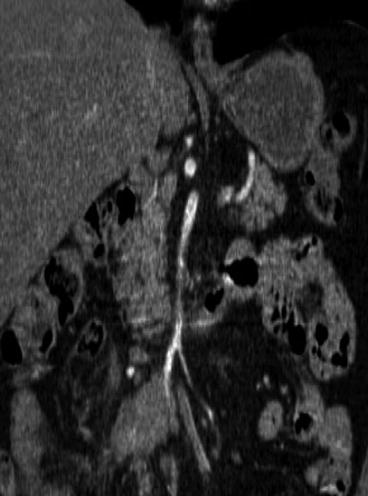

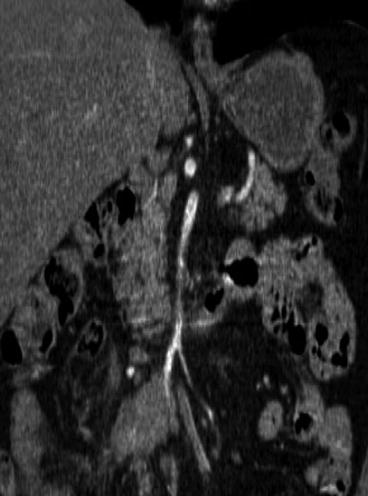

The extension below or above the horizontal duodenum (as can be depicted with coronal CT) is crucial for preoperative evaluation, as this can determine if metastases are regional or located high in the mesenteric root (Fig. 25.7). At operation the advanced Si-NETs may appear inoperable, if high mesenteric metastases with surrounding fibrosis appear to encase the mesenteric root and the major intestinal vascular supply [12, 43, 45, 49, 63]. Incautious wedge resection in the fibrotic and contracted mesentery may risk to seriously compromise the intestinal circulation. It is recommended to begin the operation with palpation of the small bowel from the Treitz ligament to the caecum, to identify the primary tumour, exclude the presence of multiple intestinal tumours and allow judgement of the length of the small intestine that needs to be removed. Ischaemic changes and venous stasis can be found to comprise limited intestinal segments, and the locoregional tumour can then be safely removed by a distal intestinal resection. This is preferably combined with caecal resection or right hemicolectomy, with proximal vascular ligature, and extended wedge resection for improved clearance of regional metastases [49]. For tumours originating in the proximal intestine, segmental small intestinal resection is performed.

Fig. 25.7

The extension below or above the horizontal duodenum (depicted with coronal CT) is crucial for evaluation of operability of an Si-NET mesenteric metastasis, as this can determine if metastases are regional or located high in the mesenteric root

With advanced growth of bulky mesenteric tumours with higher location in the mesenteric root, above the horizontal duodenum, the management can be more complex (Fig. 25.8) [12, 45, 49]. The majority of these metastases originate from distal intestinal tumours and tend to be deposited onto the right side of the main mesenteric vessels. A method has been proposed (Fig. 25.9), where the right colon and the mesenteric root are mobilised from adhesions to the retroperitoneum to the level of the horizontal duodenum and the pancreas [12, 45, 49]. Staple transection of the right colon then allows visualisation of the mesenteric artery and vein from the right side and possibility for vascular control above the mesenteric tumour during excision. With posterior view in the lifted mesenteric root, fibrotic bands can be transected and the tumour dissected from the serosa of the horizontal duodenum, occasionally, with duodenal wall excision or short duodenal resection in case of tumour invasion. It may then be possible to free-dissect the mesenteric tumour from the major vessels and carefully preserve the arcades of collateral circulation along the intestine and limit the required intestinal resection [12, 45, 49] (Fig. 25.10).

Fig. 25.8

CT image with contrast enhancement in a patient with Si-NET, where a large and high mesenteric tumour has caused intestinal ischaemia, with oedema in the terminal ileum

Fig. 25.9

Method for resection of the Si-NET primary tumour and mesenteric metastases. (a) The mesenteric tumour may extensively involve the mesenteric root and appear impossible to remove; (b) mobilisation of caecum, terminal ileum and the mesenteric root by separation of retroperitoneal attachments allows the tumour to be lifted, approached from a posterior angle and separated from the duodenum and main mesenteric vessels; and (c) tumour removed with preservation of collateral circulation along the intestine can maintain the intestinal length; the bowel can then be anastomosed and the mesenteric defect repaired (Redrawn from Åkerström et al. [45])

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree