Chapter 58 Surgical Decision-Making and Treatment Options for Chiari Malformations in Children

Significant herniation of the cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum is termed the Chiari malformation, type I (CMI). Individuals with CMI may present with symptoms, or this entity may be found incidentally. Headache is the most common presenting symptom, but hydrocephalus is found less than 10% of patients. One common presentation is scoliosis, which is found in 10% to 20% of these patients. Syringomyelia, which may or may not be the underlying etiology of the scoliosis, is present in 12% to 85% of patients.1–3 Currently, surgical treatment of the CMI is the only available treatment for symptomatic patients.

This chapter discusses the current literature regarding two aspects of surgical decision-making for children with CMI. The first is the current opinion regarding when surgery is indicated. The second is the decision regarding what operation to perform. In the absence of hydrocephalus, the first-line surgical management for CMI is a posterior fossa decompression (PFD) through a midline suboccipital craniectomy and removal of the posterior arch of the atlas with or without dural opening. If hydrocephalus is present, appropriate cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) diversion should be undertaken prior to any other surgical intervention. This may be accomplished through the insertion of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt or performance of an endoscopic third ventriculostomy.4 These points are widely accepted; however, there is controversy regarding the role of opening the dura as a component of PFD. This chapter discusses the merits and shortcomings of PFD with and without dural opening. When a dural opening is chosen, the surgeon may elect to perform further maneuvers, such as cerebellar tonsillar reduction or resection. Few studies directly compare dural opening with and without additional intradural maneuvers. This chapter therefore does not specifically address decision-making with regard to the completion of further intradural maneuvers after dural opening.

Decision-Making Regarding When to Operate

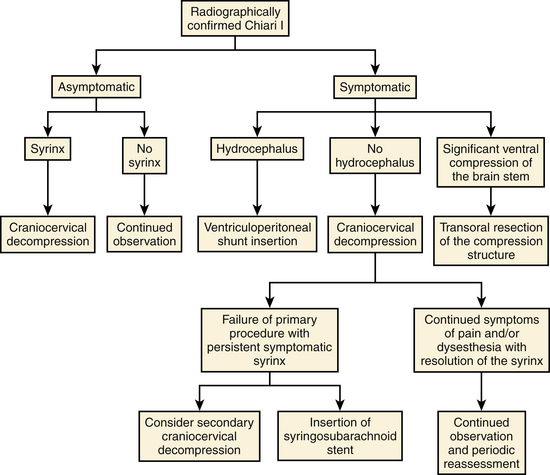

Recent publications regarding operative intervention for CMI demonstrate the varying opinions regarding both when and how to intervene.5–7,9–21 The availability of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has resulted in an increased number of asymptomatic patients being diagnosed with CMI.1 In addition to tonsillar herniation, these patients may present with asymptomatic syringomyelia and/or scoliosis. Similarly, patients may present with symptoms referable to any of these three structural lesions. Alden et al. used their experience to design a straightforward algorithm to help guide surgical decision-making.6 Our surgical decision-making tree is shown in Fig. 58-1.

Surgical Intervention for CMI

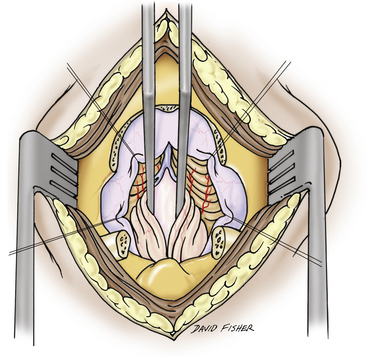

First-line surgical therapy for patients with CMI in the absence of hydrocephalus is PFD via midline suboccipital craniectomy, with appropriate removal of the posterior arch of the atlas with or without dural opening (Figs. 58-2 through 58-4). PFD attempts to reestablish bidirectional CSF flow across the craniocervical junction. This is accomplished through the expansion of the posterior fossa subarachnoid space, thus decompressing the cerebellar tonsils and brain stem. PFD may also eliminate the craniospinal CSF pressure differential that is postulated to contribute to syrinx formation.5 For the remainder of this discussion, the acronym PFD, when used alone, refers to bony suboccipital decompression with dural scoring or splitting but without frank opening of both layers of the dura mater. Most commonly, PFD is undertaken with duraplasty (PFDD) with or without cerebellar tonsil coagulation or resection. Other intradural interventions, such as fourth ventricular stenting and syrinx shunting, have been largely abandoned or are reserved for second- or third-line therapies.6–9

FIGURE 58-3 Skin incisions for PFD. The upper incision is used to harvest a periosteal graft for duraplasty.

Asymptomatic Patients

With regard to asymptomatic patients, survey data collected from the American Association of Neurological Surgeons/Congress of Neurological Surgeons section on pediatric neurosurgery in 19987 demonstrated that 83% of pediatric neurosurgeons would not operate on an asymptomatic child with CMI with or without syringomyelia. However, if the patient subsequently demonstrated asymptomatic syrinx progression, 61% of respondents would intervene. More recent international survey data9 similarly demonstrated that only a small minority (8%) of pediatric neurosurgeons would intervene for a patient with an asymptomatic CMI without syringomyelia. Rates of surgical treatment increased to 28% and 75% when the same patient presented with a thoracic syrinx of 2 and 8 mm in diameter, respectively. Novegno et al.20 conservatively managed 22 asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic children with CMI, 1 of whom had syringomyelia. Over a 5.9-year follow-up period, 17 children (77.3%) remained asymptomatic or had symptom improvement (including the patient with syringomyelia), 2 children (9%) had mild worsening of symptoms, and 3 children (13.6%) required surgical intervention. In our institution, children with asymptomatic CMI without syringomyelia do not undergo operative intervention, while those with a syrinx generally receive treatment. Asymptomatic CMI patients with scoliosis in the absence of syringomyelia are rare and should be evaluated individually.

Symptomatic Patients

There is a consensus that patients with symptomatic CMI merit surgical decompression under most circumstances. The most common presenting symptom of a child with CMI is headache. The subjective and nonspecific nature of this symptom requires neurosurgeons to apply strict criteria for a headache to be attributed to CMI. In most cases, the headache must be posteriorly located, must be of short duration, and should be exacerbated or reproduced with a Valsalva maneuver. Surgical treatment of CMI in children with other headache patterns and no additional symptoms referable to the condition may not achieve satisfactory results. Other common symptoms include neck, shoulder, and back pain; motor and sensory changes in the extremities; and sleep apnea and/or feeding difficulty in younger patients.22

In cases of progressive syringomyelia, Schijman and Steinbok9 reported that 97% of respondents would intervene and that 58% would do so in cases of CMI with progressive scoliosis in the absence of syringomyelia, although such cases are not common. McGirt et al.23 attempted to identify which patients would be most likely to have improvement in symptoms following PFD or PFDD. The authors retrospectively reviewed the clinical response of symptomatic patients who underwent preoperative cine phase-contrast MRI. They concluded that patients with preoperative CSF flow abnormalities, both ventral and dorsal to the caudal brain stem, were less likely to suffer from recurrent symptoms than were patients who lacked such evidence of preoperative CSF flow obstruction.

Decision-Making Regarding Surgical Technique

As previously discussed, once the decision to operate has been made, the surgeon must determine the extent of decompression that will be performed. The goals of surgery in the CMI population include improvement/resolution of symptoms, stabilization/improvement of scoliosis (when present), and radiologic decrease in the extent of syringomyelia (when present). With the postoperative assessment of syringomyelia, there is some debate regarding the extent of diminution that is necessary to demonstrate effective treatment.11,24 This section describes the current evidence regarding PFD with and without dural opening.

Studies Directly Comparing Surgical Techniques

Despite significant literature describing the treatment of CMI, no randomized trials comparing PFD against PFDD have been completed. Among the studies that directly compare the two techniques, only one meta-analysis and two surveys have been completed.7,9,13

Durham and Fjeld-Olenec13 published a meta-analysis of studies that directly compare cohorts of pediatric patients who underwent PFD with cohorts who were treated with PFDD. A total of seven studies met their inclusion criteria.18,19,25–29 The authors concluded that patients who undergo duraplasty are less likely to require reoperation (2.1% vs. 12.6%) for persistent or recurrent symptoms but are more likely to suffer CSF-related complications (18.5% vs. 1.8%). There was no statistical difference in clinical outcomes between the two groups, specifically with regard to symptom improvement and syringomyelia. In summary, rates of clinical improvement were 65% in the PFD patients and 79% in the PFDD patients. Rates of radiologic syrinx improvement were influenced by small numbers in some studies but were 56% in the PFD patients and 87% in those undergoing PFDD. The authors appropriately acknowledged that their conclusions were limited by the patient selection methods of the studies they examined. Among the seven papers, five studies used intraoperative ultrasound to help determine whether or not to perform a dural opening.18,19,26,28,29 The inherent subjectivity of this technique limits the degree to which the findings of each work may be generalized. Additionally, no study included a randomization or blinding process.

Using expert opinion as an indicator of current practice, Haroun et al.7 reported that 25% of survey respondents would perform PFD for children with symptomatic CMI, 32% recommended PFDD, and 55% recommended further intradural manipulations (some respondents chose more than one intervention). International survey data published by Schijman and Steinbok9 demonstrated that 76% of pediatric neurosurgeons always open the dura mater for treating CMI.

Studies of PFD without Dural Opening

Electrophysiologic evidence suggests that neurologic improvement can be achieved without a dural opening. Groups from Columbia University and Ohio State University found that improved conduction of nerve impulses through the brain stem occurs after bony decompression rather than after dural opening.30–32 As mentioned previously, multiple groups have used intraoperative ultrasound findings to aid their decision-making with regard to dural opening in children with CM-I.10,19,29,33 Yeh et al.29 found that factors that were associated with adequate decompression without duraplasty included age of less than 1 year. Factors that were more likely to be associated with the need for duraplasty included spinal symptoms (motor, sensory, or scoliosis) and a greater magnitude of tonsillar descent.

Clinical Outcome

The majority of studies that report rates of clinical and radiologic improvement following PFD also include patients who were treated with PFDD and have therefore been referenced in the preceding section. Two Italian reports demonstrated excellent results in series of patients who underwent PFD alone.11,34 Genitori et al.34 reported the results of their experience using PFD in 26 patients. Among 16 patients (61.5%) without syringomyelia, 13 (81.3%) had complete symptom resolution and the remaining 3 (18.8%) had partial resolution. Among 10 patients with syringomyelia, symptoms improved or resolved in all cases with the exception of one of three cases of scoliosis (33.3%) and one of five cases of sensory loss (20%). Rates of complete symptom resolution, however, ranged from 25% (sensory loss) to 100% (vertigo). Two patients (7.7%) required reoperation. The authors acknowledged that it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions from their study due to the small numbers in each group.

Caldarelli et al.11 reviewed their experience with PFD in 30 children. After a mean follow-up period of 4.7 years, 28 patients (93.3%) demonstrated a “significant improvement in their clinical condition.”

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree