Chapter 70 Surgical Management of Cerebellar Stroke—Hemorrhage and Infarction

Relevant Anatomy

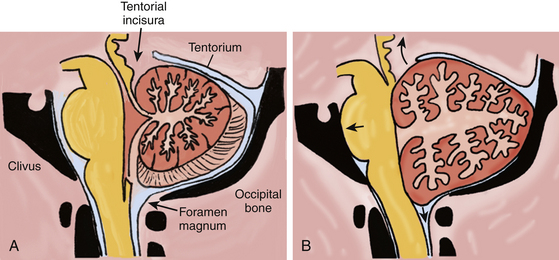

Composed of two hemispheres and a midline vermis, the cerebellum sits in the posterior fossa dorsal to the brain stem, in a space constrained by three surfaces: (1) the tentorium superiorly, (2) the skull base formed by the petrous bone and clivus ventrally, and (3) the suboccipital skull convexity surface dorsally and inferiorly (Fig. 70-1A). The posterior fossa communicates with the supratentorial space via the tentorial incisura, through which passes the upper brain stem (midbrain); and it communicates with the spinal canal via the foramen magnum, through which passes the lower brain stem (medulla) and upper cervical spinal cord.

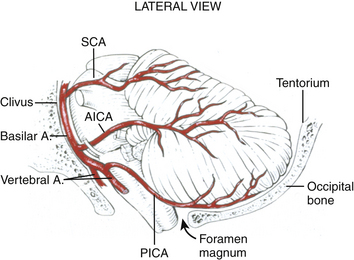

Blood is supplied to the cerebellum via three pairs of arteries from the vertebrobasilar system, each of which originates ventrally in the posterior fossa, and must encircle (and supply) the appropriate brain-stem region to reach the cerebellum (Fig. 70-2). These three trunks include: (1) the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA), which originates from the vertebral artery 1 to 3 cm proximal to the vertebrobasilar junction and supplies the lateral medulla, inferior vermis, and posterior-inferior cerebellar surface, (2) the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA), which usually originates from the inferior third of the basilar artery, and supplies the caudal pons and the petrosal surface of the cerebellum, and (3) the superior cerebellar artery (SCA), which supplies the caudal midbrain/rostral pons, the superior cerebellar peduncle and dentate nucleus, the superior vermis and the tentorial surface of the cerebellum.

Pathogenesis of Cerebellar Hemorrhage and Infarction

The infratentorial compartment, or posterior fossa, is approximately one-eighth of the entire intracranial space.1 Based on MRI volumetric analysis, the volume of the posterior fossa is approximately 200 cc in men and slightly less in women.2,3 The three components of that volume are brain parenchyma (80%), circulating blood (10%), and CSF (10%).4 An expanded cerebellum associated with a clot or edema can directly compress the brain stem against the clivus, obliterating the subarachnoid cisterns. A mass lesion in the cerebellum, such as a hematoma or edematous infarct, can also cause effacement of either the fourth ventricle or the aqueduct, and lead to obstructive hydrocephalus.

If we estimate 18-20 cc of CSF in the posterior fossa, an infarct or hematoma adding 18 cc of mass to the posterior fossa is sufficient to displace the entire volume of CSF in this compartment. After the CSF reserve space is obliterated, any further enlargement of the hematoma or edema of the surrounding brain and/or infarction reduces the volume of circulating blood, and begins to force brain parenchyma out of the posterior fossa through the tentorial incisura or the foramen magnum (Fig. 70-1B). Given that the volume of a sphere is 4/3×πr3 (where r is the radius), an 18-cc spherical hematoma with a diameter of 3.2 cm (radius 1.6 cm) correlates with the popular assertion that a 3-cm cerebellar hematoma usually warrants urgent surgical evacuation. The causes of cerebellar infarction and hemorrhage are outlined in Table 70-1.

Table 70-1 Causes of Cerebellar Hemorrhage and Infarction

| Cerebellar Hemorrhage | Cerebellar Infarction |

|---|---|

| Hypertension | Vertebral artery atherosclerosis |

| Coagulopathy | Cardioembolism |

| Amyloid angiopathy | Artery to artery embolism |

| Hemorrhagic transformation of an infarct | Patent foramen ovale |

| Tumor | Vertebral artery dissection |

| Arteriovenous malformation | Hypercoagulable states |

| Cavernous malformation | Vasculitis |

| Supratentorial surgery with cerebral spinal fluid drainage | Venous sinus thrombosis |

| Spinal surgery with durotomy | Cocaine use |

Hemorrhage

Hypertension is the most common identifiable risk factor for cerebellar hemorrhage, occurring in 36% to 89% of cases in various series.5 Hematomas occur in the cerebellar hemisphere and vermis with roughly equal frequency, and may extend into the ventricular system. The SCA and AICA territories are more often involved, particularly in the region of the dentate nucleus, which is supplied by perforating arteries from the SCA.6 A few cases of microaneurysms have been reported in histopathologic studies of perihemorrhagic tissue.7

Less frequent causes of cerebellar hemorrhage are coagulopathy (typically warfarin use), amyloid angiopathy, hemorrhagic transformation of an infarct, tumors, and vascular malformations.8–10 Remote cerebellar hemorrhage related to the release of large volumes of CSF intra- or peri-operatively has been well described in the literature as an unexpected outcome of supratentorial or spinal surgery.11–14

Infarction

The most common cause of cerebellar infarction in older patients is vertebral artery atherosclerosis, which may be intracranial, extracranial, or both. The PICA distribution is the most likely territory involved clinically. Cardiac and artery-to-artery embolization is also an important cause, and may explain “nonterritorial” infarcts that involve smaller regions of the cerebellum.15 In patients under age 40, patent foramen ovale is an important consideration.16 Vertebral artery dissection is another important cause, with or without a history of trauma, chiropractic manipulation, or prolonged neck hyperextension (“beauty parlor stroke”). Most infarcts caused by vertebral artery dissection also occur in the PICA territory.17

Less common disorders associated with cerebellar infarction include hypercoagulable states, vasculitis, venous sinus thrombosis, and cocaine use.16 Such infarcts may involve the typical PICA, SCA, or AICA territories, watershed regions, or smaller, nonterritorial areas.15

Clinical Manifestations

While cerebellar stroke is the most worrisome cause of dizziness, nausea, and gait instability, the same constellation of symptoms may result from a peripheral disorder, such as vestibular neuritis or labyrinthitis. Furthermore, the clinical presentation of cerebellar hemorrhage is not reliably distinct from that of cerebellar infarction. In Raco’s series comparing 70 patients with cerebellar hemorrhage and 52 patients with cerebellar infarction, both entities commonly presented with the acute onset of nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and unsteady gait. Headache was more common as an initial symptom in cerebellar hemorrhage.6 Dizziness may occur with or without vertigo.16 On physical exam, dysarthria, ataxia, and nystagmus are common. Ataxia may be appendicular, axial or both, depending on the relative involvement of the cerebellar hemispheres and vermis. Nystagmus and/or hearing loss may be a sign of cerebellar stroke or of a peripheral vestibular disorder.16

Posterior circulation strokes, particularly infarction, often involve both the cerebellum and the brain stem. In such situations, various brain-stem stroke syndromes are evident in combination with the manifestations of cerebellar dysfunction. Depending on the level affected, these syndromes may include ipsilateral hemifacial analgesia, contralateral hemibody analgesia, Horner’s syndrome, motor deficits, and cranial neuropathies (Table 70-2). The neurologic deficit often indicates the arterial territory affected by the infarct, but anatomic variations are common between AICA and PICA, and the territory affected can vary considerably.

Table 70-2 Posterior Circulation Stroke Syndromes

| Infarct Territory | Clinical Features |

|---|---|

| Posterior inferior cerebellar artery (lateral medullary syndrome or Wallenberg’s syndrome) | |

| Anterior inferior cerebellar artery (Foville’s syndrome) | |

| Superior cerebellar artery (Mill’s syndrome) | |

| Cerebellar stroke with secondary brain-stem compression |

Distinguishing the signs of primary brain-stem stroke from those of secondary brain-stem compression is extremely important. Direct brain-stem compression can manifest either as gaze restrictions, lower cranial nerve dysfunction, or altered sensorium from suppression of the reticular activating system. After the early symptoms and signs of the infarction are defined, delayed neurologic deterioration 1 to 7 days following symptom onset is often indicative of cerebellar swelling and impending upward (transtentorial) or downward (tonsilar) herniation.18–23 Hydrocephalus may further contribute to the decline. Certainly, any change in sensorium warrants urgent surgical intervention, as the patient can quickly proceed through the later stages of brain-stem compression, which include coma, abnormal respirations, posturing, and death.