65 Surgical Resection of Spinal Vascular Lesions

I. Key Points

– The natural history of spinal vascular lesions is usually malignant. Given the eloquence of local tissue, early definitive treatment is favored whenever feasible.

– All arteriovenous (AV) lesions require preoperative spinal angiography.

– Preservation of the anterior spinal artery (ASA) is paramount during attempts at surgical treatment or embolization.

– The optimal trajectory for the resection of spinal cavernous malformations is determined by the two-point method. A line connecting the center of the lesion with its most accessible margin determines the approach. Some lesions without pial contact may still be resected.

– Timing of surgical intervention after hemorrhage is controversial, although the presence of acute hemorrhage may aid in early resection of some cavernomas.

II. Indications

– Cavernous malformations: Surgery is recommended for all accessible lesions that reach a pial surface. Small, deep-seated asymptomatic lesions can be followed. Deep lesions with evidence of repeated hemorrhage or expansion should be considered for surgery.1

– Extradural-intradural AV malformations (AVMs): Palliative attempts at flow reduction and/or selective targeting of high-risk features are appropriate in the setting of progressive symptoms related to steal, repeated hemorrhage, mass effect, or congestion.

– Intramedullary and conus AVMs: Surgical resection, typically with preoperative embolization, is recommended if gross total excision can be achieved. Embolization alone for cure has been demonstrated but remains more controversial.

– Intradural-dorsal and intradural-ventral AV fistula (AVF): all require definitive treatment with either surgery or nonparticulate embolization. If clinical history and imaging findings suggest an intradural-dorsal AVF despite a negative angiogram, surgical exploration is warranted.

– Extradural AVF: all require definitive treatment; endovascular intervention is favored.

III. Technique

– Posterior or posterolateral approach via laminectomy or laminoplasty

• Added costotransversectomy or facetectomy may allow further lateral exposure.

• The dura is opened in a linear fashion and the arachnoid is tacked to the dura.

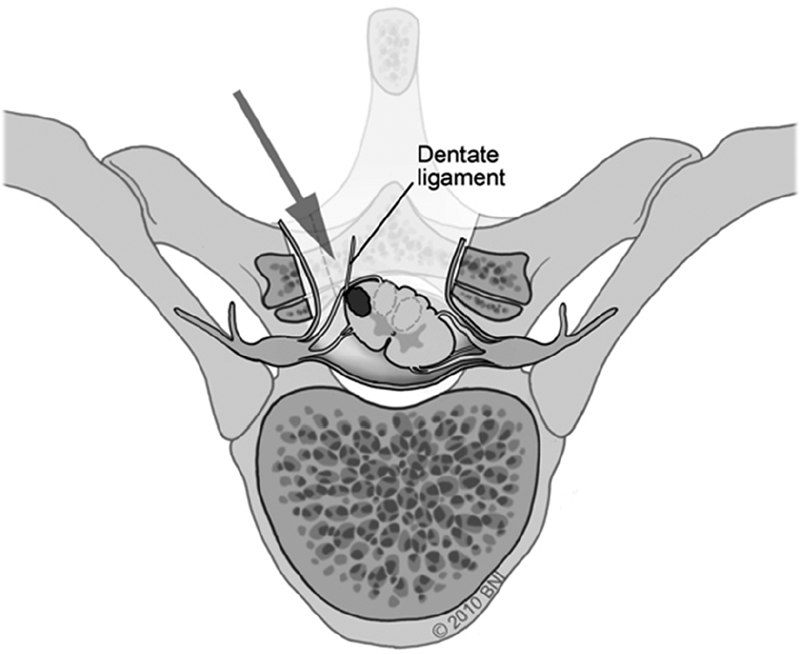

• If additional anterolateral visualization is necessary, the dentate ligaments may be transected and tacked contralaterally with 6-0 Prolene suture to facilitate gentle rotation of the spinal cord. This may be done across several levels for maximum effect (Fig. 65.1).

– Cavernous malformations

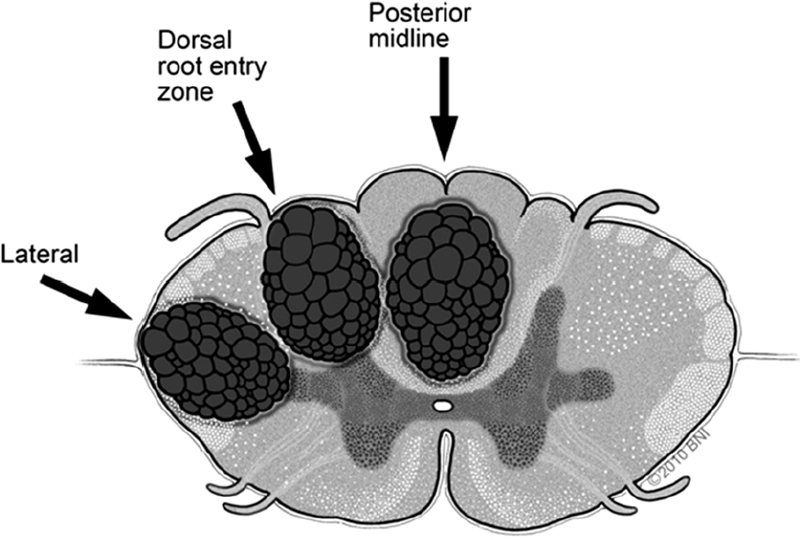

• When necessary, myelotomy is made sharply with a linear pial opening. Appropriate zones for entry into the cord include the dorsal midline and the lateral dorsal sulcus at the dorsal root entry zone. This trajectory enters the substantia gelatinosa. A third entry option is the lateral trajectory behind the dentate ligaments and between the dorsal and ventral spinocerebellar tracts (Fig. 65.2).

• The lesion is dissected circumferentially. Coagulation of the cavernoma may be necessary to shrink and debulk the lesion’s interior. The associated venous anomaly should be preserved. Surrounding hemosiderin-stained spinal cord is not taken.1

– Intradural-dorsal AVFs: Following dural opening, the arterialized vein is followed to its intradural interface along the root sleeve, where the radicular artery pierces the dura. The intra-dural fistulous connection is clipped, bipolared, and transected.

– Extradural AVF: transarterial endovascular coil embolization is typically the preferred modality of treatment, although transvenous routes have been described.

– Intradural-ventral AVFs: Anterior and posterolateral trajectories have been described. The fistula is bipolared and transected such that arterial supply to the ASA and normal venous drainage is preserved. Venous varices can be further excised. Nonparticulate embolization may be useful in selected cases, although surgery remains the gold standard.

– Intramedullary spinal AVMs: Arterial rather than venous feeders should be sharply dissected circumferentially, cauterized, and transected first. The largest draining vein is typically cauterized and transected last for removal of the specimen.

– Extradural-intradural AVMs: Embolization may be the primary palliative modality for the setting of symptomatic steal, repeated hemorrhage, or vascular congestion. Surgery is typically reserved for relief of persistent, symptomatic mass effect.

Fig. 65.1 Gentle spinal cord rotation is facilitated by retraction of dentate ligament(s) (used with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute).

Fig. 65.2 Alternative posterior and posterolateral zones of entry for myelotomy (used with permission from Barrow Neurological Institute).

IV. Complications

– Cerebrospinal fluid leak, wound complications.

– Delayed or acute neurologic decline: May be attributable to progressive venous thrombosis, especially in the setting of embolization for intradural-dorsal AVFs. Routine postprocedural heparinization is considered in these patients. Blood pressure control is strict, and judicious use of steroids is advised before intervention.

V. Postoperative Care

– Postprocedural angiography and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is essential to verify treatment effect, especially in the setting of new neurologic deficits.

VI. Outcomes

– Cavernous malformations: Subtotal resection offers nominal benefit. Initial postoperative deterioration has been reported in 24 to 50%, but long-term follow-up data suggest improved neurologic function in as many 46 to 58%.

– Intradural-dorsal AVFs: The primary benefit of surgery over endovascular treatment remains risk of recurrence (as high as 98% initial success for surgery vs. 46 to 85% for embolization).2 Endovascular abilities are improving. Motor improvements have been reported in approximately 60% of patients compared with 40% showing improvements in sphincter dysfunction (Aminoff-Logue [AL] Scale, Table 65.1), irrespective of treatment modality. Numerically, improvements in AL scores are typically modest (about one point).

– Intradural-ventral AVFs: Available series are mostly small, but neurologic improvement or stabilization following surgery has been reported to range from 87.5 to 95%. Preoperative embolization may be useful in limiting flow rate (and in some cases for cure), but incomplete occlusion has resulted in more modest improvements compared with surgery.3

– Extradural AVFs: Outcomes reported in numerous case reports have been favorable in terms of fistula obliteration and clinical improvement. In the setting of acute hematoma, surgical evacuation within 12 hours is an important prognostic.

– Extradural-intradural AVMs: Most multimodality attempts are purely palliative. Rare cases may be amenable to embolization followed by operative resection.

– Intramedullary AVMs: Clinical improvement rates of 33 to 67% have been reported for surgery, compared with rates of 8 to 20% for clinical decline. Rates of postsurgical angiographic cure have ranged from 59 to 100%. Further endovascular data using Onyx is anticipated. The most appropriate and definitive strategy remains preoperative embolization (when technically appropriate) followed by microsurgical excision.

– Conus AVMs: Little published experience. Aggressive multimodality treatment can result in clinical improvement or stabilization in addition to angiographic cure.

Table 65.1 Aminoff-Logue Scale

| Gait dysfunction |

| 1. Leg weakness or gait change without significant activity impairment |

| 2. Restricted walking but no DME assist required |

| 3. Cane for ambulation |

| 4. Crutches or walker for ambulation |

| 5. Bed-bound, does not stand, confined to wheelchair |

| Urinary dysfunction |

| 1. Hesitancy, urgency, and/or frequency |

| 2. Intermittent incontinence or retention |

| 3. Full incontinence or retention |

Abbreviation: DME, durable medical equipment.

Source: Modified from Aminoff MJ and Logue V. The Prognosis of Patients with Spinal Vascular Malformations. Brain 1974;(97):211–218.

VII. Surgical Pearls

– Intraoperative electrophysiologic monitoring of somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEPs) and motor evoked potentials (MEPs) is essential for all cases. In the setting of AV lesions, serial indocyanine green angiography (ICG) and/or intraoperative spinal angiographic runs before and during resection are often useful.

– Anterior or anterolateral approaches to the resection of spinal vascular lesions are seldom advised due to the risk of ASA compromise and poor dural closure.4

– Sharp rather than blunt dissection is favored when possible.

– If required, myelotomy should expose the entire cranial-caudal extent of the lesion to minimize parenchymal retraction and aid in visualizing feeding pedicles.

– Pressure measurements in the arterialized veins of intradural dorsal AVFs can be transduced using a small-gauge needle. Pressure should more closely approximate central venous pressure following fistula obliteration.

Common Clinical Questions

1. Name the primary advantage of surgery (in terms of outcome) over embolization for intradural-dorsal AVFs.

2. Name three zones of entry for myelotomy from a posterior approach.

3. Name three intraoperative tools or strategies useful in guiding and confirming treatment for AVMs and AVFs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree