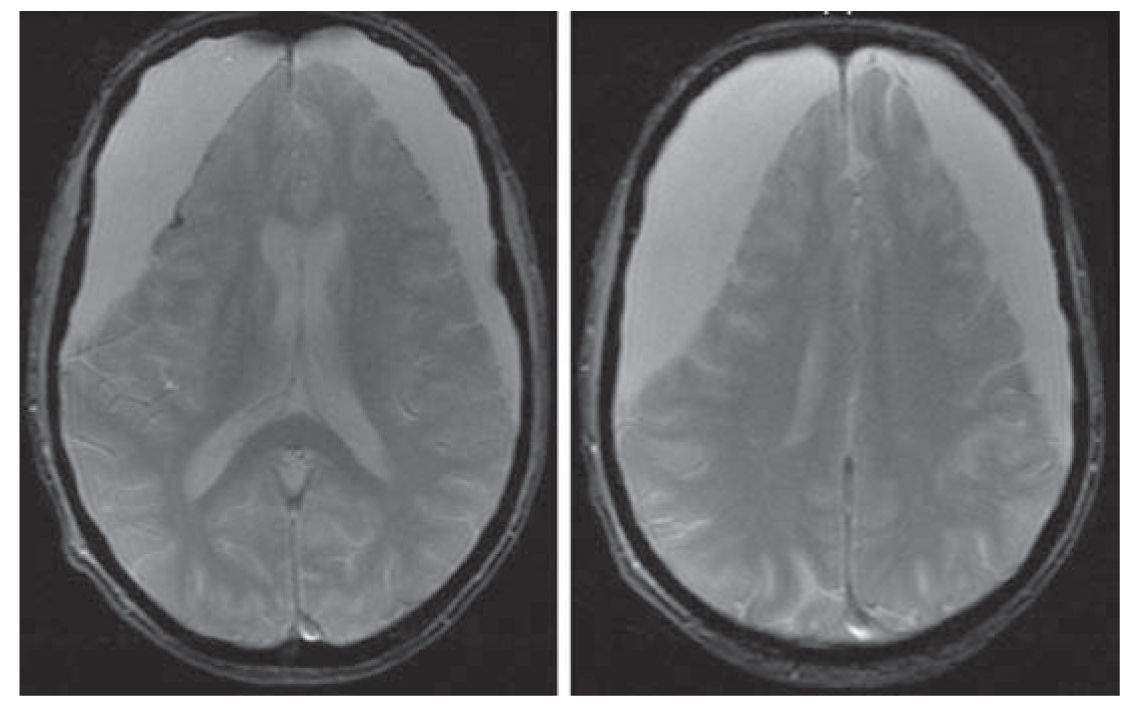

FIGURE 63.1 Axial T1-weighted MR images demonstrate diffuse abnormal enhancement extending along the ependymal surface of the left lateral ventricle and third ventricle consistent with ventriculitis/ependymitis in a 65-year-old man with Streptococcus constellatus meningitis.

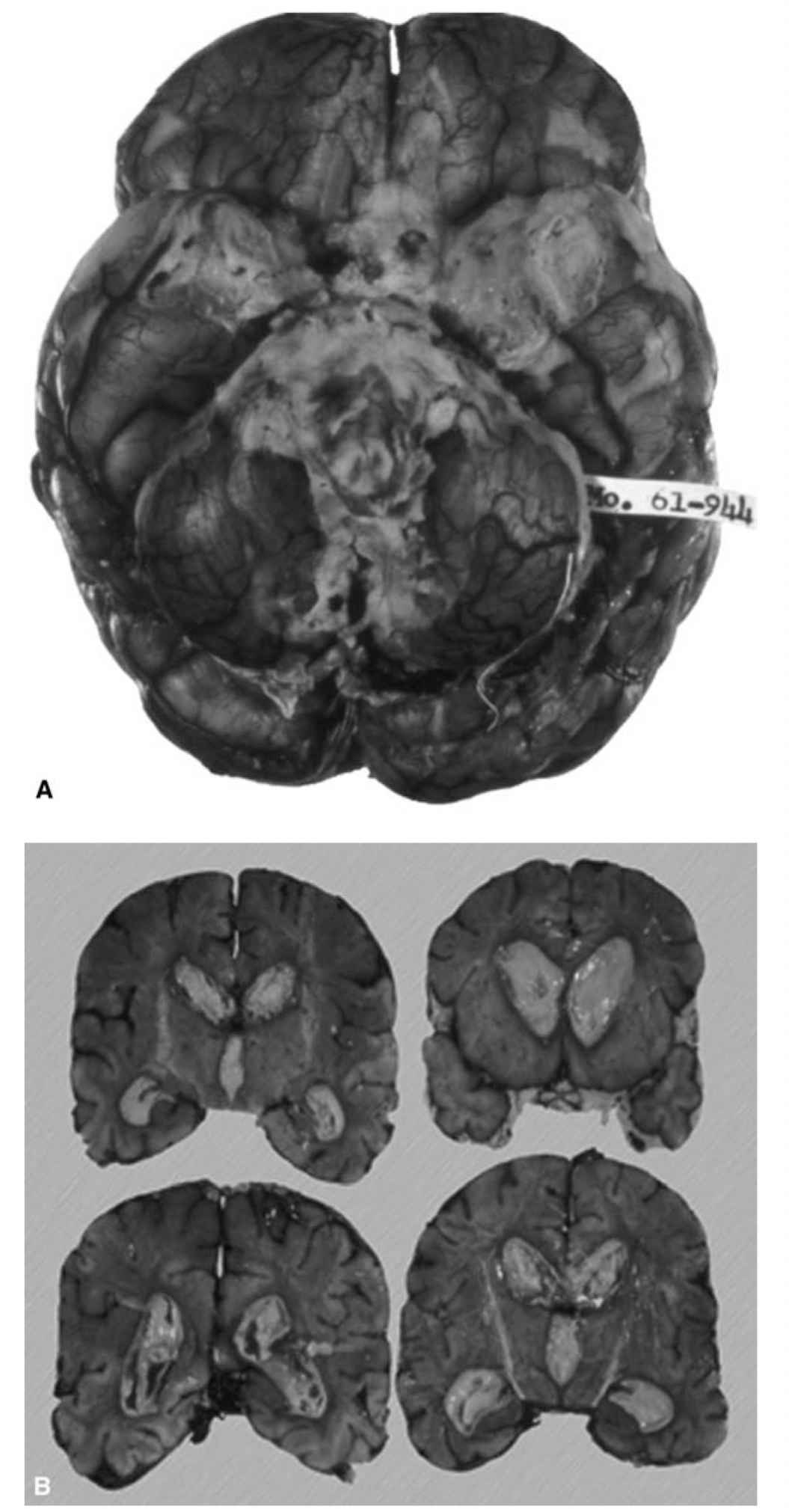

FIGURE 63.2 A: Gross image of pyogenic meningitis. B: Cross section of pyogenic ventriculitis. (See color plates.)

J. Chemoprophylax household contacts and those with direct exposure to droplet secretions of patients with meningococcal and Haemophilus influenzae infection with rifampin 600 mg twice daily for 2 days.

K. Neuroimaging

L. Serum procalcitonin and C-reactive protein (CRP) can help differentiate bacterial from viral meningitis.

HERPES SIMPLEX ENCEPHALITIS

A. Most common cause of fatal sporadic encephalitis

B. Treatment. acyclovir IV 10 mg/kg every 8 hours for 14 to 21 days. Adjust dose for renal function and maintain adequate hydration to prevent crystal nephropathy.

C. Control seizures.

D. Neuroimaging

E. Predictors of poor outcome include age greater than 30 years, GCS less than 6, delayed initiation of acyclovir treatment more than 4 days after symptom onset

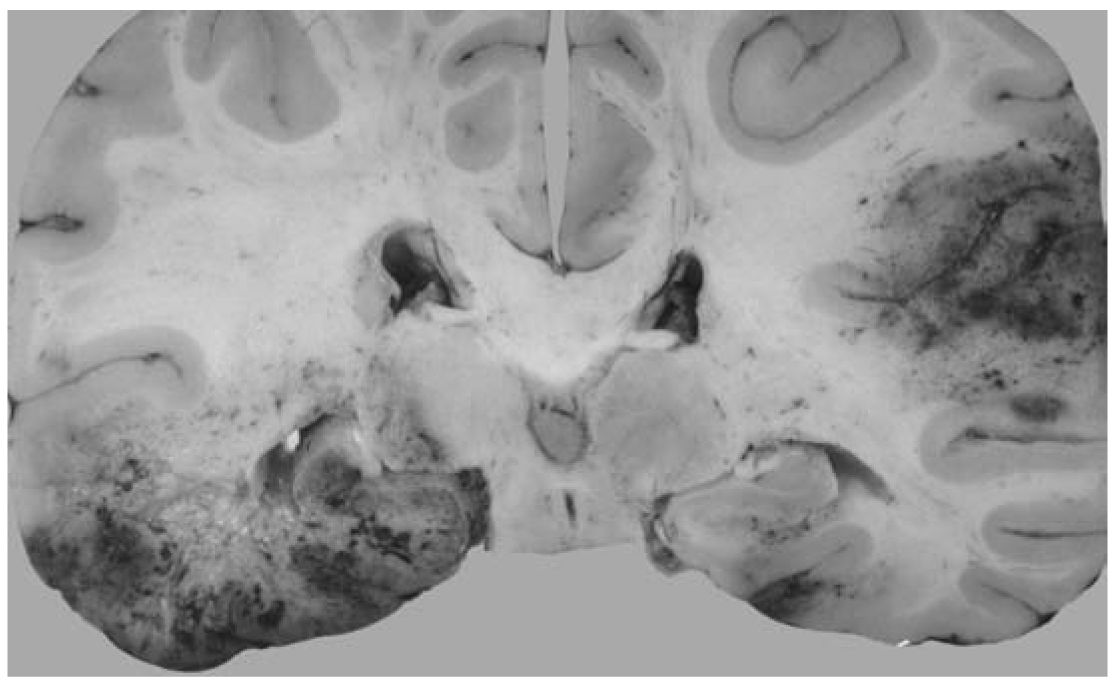

F. Untreated herpes simplex encephalitis has a 70% mortality rate (Fig. 63.3).

BRAIN ABSCESS

A. Classify according to suspected entry point of infection, which predicts microbial flora and guides empiric antimicrobial treatment.

1. Most common source is direct or indirect seeding through emissary veins from paranasal sinus, middle ear, and teeth.

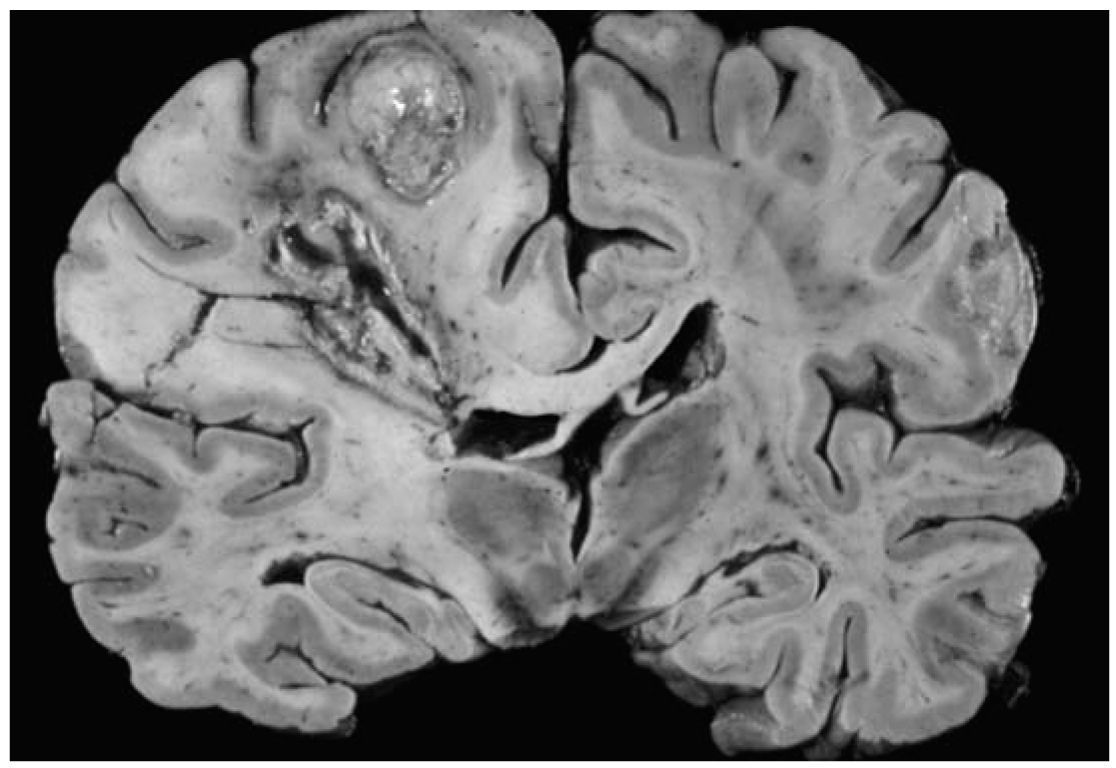

2. Underlying pathology such as stroke or neoplasm can serve as a focus for abscess (Fig. 63.4).

FIGURE 63.3 Cross section of the brain in a patient who had herpes simplex virus encephalitis. (See color plates.)

FIGURE 63.4 Cross section of the brain in a patient who had multiloculated cerebral abscesses. (See color plates.)

B. Gadolinium-enhanced MRI brain.

1. Allows for early recognition of cerebritis or abscess

2. Permits precise localization needed for surgical treatment

3. Serial MRI for treatment monitoring

4. Contrast-enhanced CT brain if MRI contraindicated

C. Antimicrobial treatment.

1. Antibiotics should not be withheld unless surgery is to be performed within several hours and no significant mass effect is present to preserve yield of positive cultures.

2. Community acquired. Third-generation cephalosporin: ceftriaxone (Table 63.1) (can also choose ceftazidime or cefotaxime) plus vancomycin (Table 63.1) plus metronidazole 500 mg every 6 hour in adults and 7.5 mg/kg every 8 hour in children.

3. Postoperative or posttraumatic. Meropenem or cefepime plus vancomycin.

4. Bone marrow transplant, stem cell transplant, solid organ transplant. Consider voriconazole and anti-toxoplasma therapy.

5. Nocardial abscess. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole ± aspiration/excision.

6. Aspergillosis. Voriconazole

7. Mucormycosis. Liposomal amphotericin B

8. Coccidiomycosis. Fluconazole or itraconazole

9. Blastomycosis. Liposomal amphotericin B

10. Histoplasmosis: Liposomal amphotericin B × 3 months, then itraconazole × 12 months

11. Candidiasis. Combination IV liposomal amphotericin B plus oral flucytosine

12. Cryptococcus. Induction: combination liposomal amphotericin B plus flucytosine. Consolidation after 2 weeks: fluconazole 400 mg daily for 8 to 10 weeks for immunocompetent and 6 to 12 months for immunosuppressed patients

13. Actinomycosis. High-dose IV penicillin for 2 to 6 weeks, followed by P.O. amoxicillin, ampicillin, or penicillin for 6 to 12 months. Doxycycline, erythromycin, and clindamycin are also options.

14. Consider steroids for patients with significant mass effect due to vasogenic cerebral edema although there are no data supporting routine use.

D. Consider surgery for any abscess larger than 2.5 cm.

1. Aspiration is valuable for deep-seated abscesses. Excision allows for detection and treatment of extracranial communication.

2. Consider surgical treatment of primary infectious focus.

E. Treat complications including seizures, hyponatremia, obstructive hydrocephalus, ventriculitis, and cerebral edema.

A. High risk in HIV patients with CD4+ T cell counts less than 100 cells/µL or less than 200 cells/µL in the setting of concomitant opportunistic infection or malignancy

B. Treat with pyrimethamine 200 mg once then weight-based dosing.

C. Less than 60 kg. Pyrimethamine 50 mg P.O. daily plus sulfadiazine 1,000 mg P.O. q6h plus leucovorin 10 to 25 mg P.O. daily. Consider increasing to 50 mg daily or twice daily.

D. Greater than 60 kg. Pyrimethamine 75 mg P.O. daily plus sulfadiazine 1,500 mg P.O. q6h plus leucovorin 10 to 25 mg P.O. daily. Consider increasing to 50 mg daily or twice daily.

E. If patient is allergic to sulfa, consider clindamycin 600 mg IV or P.O. q6h.

F. Therapy duration: 6 weeks or longer if no clinical and radiologic improvement.

G. If no improvement after 10 to 14 days of therapy, consider alternative diagnosis.

SEPTIC CAVERNOUS SINUS THROMBOSIS

A. Etiology.

1. Common. Middle third facial infections and paranasal sinusitis

2. Less common. Otogenic, odontogenic, pharyngeal, and distant septic foci

3. Common organisms: Staphylococcus aureus (69%), Streptococcus (17%), Pneumococcus (5%), gram-negative species (5%), Bacteroides (2%), and Fusobacterium (2%)

B. Clinical features. Fever, tachycardia, hypotension, emesis, confusion, coma, chemosis, periorbital edema, ptosis, Horner’s syndrome, ocular motility impairment, visual loss, papilledema, retinal vein dilatation, and pituitary insufficiency

C. Imaging.

1. CT brain provides bony details and air–soft tissue interface.

2. MRI brain has superior soft tissue resolution.

D. Treatment.

1. Antimicrobial therapy. Third-generation cephalosporin (ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, or cefotaxime), metronidazole, and vancomycin for at least 2 weeks.

2. Surgical treatment of nondraining primary infectious focus

3. Consider Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology consults.

4. Consider IV steroids for cranial nerve dysfunction or orbital inflammation after antimicrobial therapy initiated although evidence is limited.

5. Limited evidence regarding use of adjunctive anticoagulation

a. Anticoagulation can be used safely in the absence of intracranial or systemic bleeding for patients deteriorating despite antimicrobial therapy.

b. Target. twice baseline activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT).

c. Duration. 2 weeks to 3 months.

SUBDURAL EMPYEMA

A. Uncommon, suppurative, and loculated infection between the dura mater and the arachnoid; 95% intracranial and 5% spinal

B. Often unilateral and spreads rapidly throughout subdural space. Fatal if untreated

C. Etiology.

1. Paranasal sinusitis, meningitis, otitis media, mastoiditis, trauma, neurosurgical procedures, secondary infection of subdural hematoma (SDH) or hygroma, dental caries, and distant site infection (e.g., lungs) with hematogenous spread

2. Most common organisms.

a. Paranasal sinusitis. Anaerobes, microaerophilic Streptococci.

b. Neurosurgical procedures. Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Staphylococcus epidermidis.

c. Postoperative/posttraumatic. Staphylococcus aureus.

d. Otitis media. Streptococci species, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bacteroides.

e. Neonates. Enterobacteriaceae, Group B streptococci, Listeria monocytogenes.

f. AIDS. Salmonella.

D. Clinical features. Fever, seizures, headaches, vomiting, periorbital edema, sinusitis, meningismus, contralateral sensorimotor loss, mental status changes, stupor and coma.

1. Gadolinium-enhanced MRI.

2. Contrast-enhanced CT if MRI contraindicated (lower sensitivity and specificity for intracranial subdural empyema compared to MRI)

3. LP. contraindicated if elevated ICP or spinal cord effacement present.

4. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and CRP.

F. Complications include seizures, cerebral infarction, cavernous sinus thrombosis, hydrocephalus, cerebral edema, and cranial/spinal osteomyelitis.

G. Treatment.

1. Empiric vancomycin plus third-generation cephalosporin (ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, cefotaxime) plus metronidazole

2. Early surgical drainage

3. Drainage of primary contiguous focus

ISCHEMIC STROKE: WITHIN 3 HOURS OF LAST KNOWN WELL

A. No intracranial hemorrhage on CT ![]() (Fig. 63.5; Video 63.1)

(Fig. 63.5; Video 63.1)

B. Age 18 years or older

C. IV tPA (alteplase) 0.9 mg/kg (maximum dose of 90 mg); 10% of total dose as bolus over 1 minute; and remainder infused over 60 minutes

FIGURE 63.5 CT brain without contrast. Hyperdense left MCA sign in a patient presenting with nonfluent aphasia and right hemiplegia. CT, computed tomography; MCA, middle cerebral artery.

1. Stroke or serious head injury within 3 months

2. Frank hypodensity on CT more than 1/3 the MCA territory

3. Recent intracranial or intraspinal surgery

4. History of intracranial hemorrhage

5. Persistent systolic BP above 185 mm Hg or diastolic BP above 110 mm Hg despite reasonable attempts to reduce it

6. Intracranial neoplasm, arteriovenous malformation, or aneurysm

7. Symptoms suggestive of SAH

8. Active internal bleeding

9. Arterial puncture at a noncompressible site within 7 days

a. Vitamin K antagonist or heparin used within 48 hours AND elevated aPTT, international normalized ratio (INR) above 1.7, or PT more than 15 seconds

b. Other oral anticoagulant used within 48 hours

10. Platelet count below 100,000/µL

11. Blood glucose below 50 mg/dL

12. Relative contraindications.

a. Recent surgery or major trauma within 14 days

b. Pregnancy

c. Gastrointestinal (GI) or urinary tract hemorrhage within 21 days

d. Myocardial infarction within 3 months

e. Rapidly improving or minor neurologic deficits likely to result in minimal or no deficit

E. No antithrombotic agents including VTE prophylaxis for 24 hours after IV tissue plasminogen activator (tPA)

F. Maintain BP below 180/105 mm Hg for 24 hours after IV tPA

G. Avoid IV enalaprilat as it increases risk of angiolingual edema associated with IV tPA.

ISCHEMIC STROKE 3 TO 4.5 HOURS FROM LAST KNOWN WELL

A. Exclusion criteria. In addition to above (Section D under Ischemic Stroke: Within 3 Hours of Last Known Well) exclusion criteria though not absolute, practitioners can consider the following exclusion criteria:

1. Age older than 80 years

2. National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) above 25

3. Combination of previous stroke and diabetes mellitus

4. Oral anticoagulant use regardless of INR values

B. Endovascular intervention for ischemic stroke utilizing modern stent retrievers

1. Inclusion criteria.

a. Prestroke modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score 0 to 1

b. IV tPA administered within 4.5 hours

c. Age 18 years or older

d. Occlusion of internal carotid artery (ICA) terminus or proximal MCA (M1)

e. NIHSS 6 or higher

f. Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECTS) 6 or higher (endovascular treatment for ASPECTS less than 6 is uncertain)

g. Groin puncture can be achieved within 6 hours of symptom onset

2. Effectiveness of endovascular treatment initiated beyond 6 hours is uncertain.

C. Endovascular treatment within 6 hours for anterior circulation occlusion is reasonable for patients with contraindications to IV tPA or those with occlusion of M2 or M3 portions of MCA, anterior cerebral arteries, vertebral arteries, or basilar artery.

D. Endovascular treatment is recommended over intra-arterial tPA within 6 hours.

E. Conscious sedation is preferred over general anesthesia if patient can protect airway.

F. CT brain should be completed prior to treatment and vascular imaging (CTA or MRA) is recommended. Benefits of perfusion imaging (CT/MRI) are uncertain.

G. Monitor patient in a neuroscience intensive care unit (NICU) after treatment.

ANGIOLINGUAL EDEMA ASSOCIATED WITH IV TPA ADMINISTRATION

A. Increased risk in patients on angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs)

B. Maintain airway.

1. Endotracheal intubation may not be necessary if edema is limited to anterior tongue and lips.

2. Edema involving larynx, palate, floor of mouth, or oropharynx with rapid progression (within 30 minutes) poses higher risk of requiring intubation.

3. Awake fiberoptic intubation is optimal. Nasal-tracheal intubation may be required though poses risk of epistaxis post-tPA. Cricothyroidotomy is rarely needed and also problematic post-IV tPA.

C. Discontinue IV tPA infusion and hold ACEI.

D. Give IV methylprednisolone (IVMP) 125 mg, and diphenhydramine 50 mg IV.

E. Supportive care.

MALIGNANT CEREBRAL EDEMA

A. Associated factors include NIHSS above 20 (left hemispheric stroke) compared to above 15 (right hemispheric stroke), ICA terminus occlusion, impaired consciousness, headache, nausea/vomiting, leukocytosis, imaging 50% or greater MCA territory involvement on imaging, and additional involvement of ACA and PCA territories.

B. Decompressive hemicraniectomy within 48 hours after symptoms onset combined with best medical management in patients 18 to 60 years old with NIHSS 15 or higher, decreased level of consciousness, intact pupil reactivity, and at least 50% involvement of MCA territory on CT improves outcomes compared to best medical management alone.

1. Fronto-temporo-parietal decompressive hemicraniectomy and durotomy at least 12 cm in diameter with extension to the floor of the middle cranial fossa with preservation of the superficial temporal artery and facial nerve branches.

2. Mortality. 28% surgical versus 78% conservative.

3. Functional outcome.

a. mRS 1 to 4 at 12 months: 75% surgical versus 24% conservative.

b. mRS 1 to 3 at 12 months: 43% surgical versus 21% conservative.

4. Number needed to treat (NNT).

a. mRS 0 to 4: 2

b. mRS 0 to 3: 3

c. Survival: 2

C. Decompressive hemicraniectomy within 48 hours in patients 61 to 82 years old increases survival and decreases severe disability.

1. Mortality: 43% surgical versus 76% conservative

2. Functional outcome.

a. mRS 0 to 2: 0% surgical versus 0% conservative

b. mRS 3 to 4: 38% surgical versus 16% conservative

3. NNT.

a. mRS 3 to 4: 4.5

b. Survival: 3

MANAGEMENT OF INTRACRANIAL BLEEDING AFTER THROMBOLYTIC THERAPY

A. No evidence-based guidelines

B. Stop thrombolytic infusion.

C. CBC, PT/INR, aPTT, fibrinogen, and type and cross-match

D. STAT head CT

E. Cryoprecipitate (includes factor VIII): two adult doses infused over 10 to 30 minutes.

F. Platelets. One adult dose infused over 10 to 30 minutes.

G. Consider tranexamic acid. 1,000 mg IV infused over 10 minutes OR epsilon-aminocaproic acid 4-5 grams over 1 hour, followed by 1 gram IV until bleeding is controlled.

H. Consider hematology and neurosurgery consultations.

I. Supportive therapy including ICP, CPP, MAP, temperature, and glucose control.

FIGURE 63.6 Axial gradient echo MRI shows large bilateral chronic SDHs. The right-sided SDH is slightly larger than the left. There is approximately 2 mm of right-to-left subfalcine shift. There is also evidence of previous hemorrhage along the lateral cortical surface of the right frontal lobe. The patient was an 83-year-old man with atrial fibrillation, on warfarin, who reported a subacute history of memory loss. INR on admission was 2.4. INR, international normalized ratio; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SDH, subdural hematoma.

MANAGEMENT OF INTRACRANIAL BLEEDING ASSOCIATED WITH WARFARIN

A. Discontinue warfarin (Figs. 63.6 and 63.7).

B. Vitamin K 10 mg slow IV injection

C. Four-factor (II, VII, IX, and X) prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC): 25 to 50 units per kg body weight based on INR plus fresh frozen plasma 10 to 15 mL/kg

D. Rapid reversal is crucial.

E. Consider neurosurgery consultation.

F. Recombinant FVIIa not routinely recommended.

MANAGEMENT OF INTRACRANIAL BLEEDING ASSOCIATED WITH HEPARIN

A. Discontinue heparin.

B. Protamine sulfate. 1 mg/100 U of heparin administered in the preceding 4 hours infusion not to exceed 50 mg every 10 minutes. Adjust dose according to elapsed time from last heparin dose:

1. 20 to 60 minutes. 0.5 to 0.75 mg/100 U of heparin.

2. 60 to 120 minutes. 0.375 to 0.5 mg/100 U of heparin.

3. More than 120 minutes. 0.25 to 0.375 mg/100 U of heparin.

MANAGEMENT OF INTRACRANIAL BLEEDING ASSOCIATED WITH NOVEL ORAL ANTICOAGULANTS

A. Stop novel oral anticoagulants (NOAC).

B. Check PT, INR, PTT, fibrinogen, and platelet count.

C. Treatment.

1. Direct thrombin inhibitor (e.g., dabigatran). Four-factor PCC. Consider hemodialysis and activated charcoal if ingested within 2 hours. A fast acting antidote Idaruzizumab (Praxbind) has been recently approved by the US FDA.

2. Anti-Xa agent (e.g., rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban). Four-factor PCC. Consider activated charcoal within 3 hours for apixaban and edoxaban and up to 8 hours for rivaroxaban.

D. Other specific antidotes are currently in development.

FIGURE 63.7 CT brain without contrast. Right temporo-parietal warfarin-related ICH with evidence of subfalcine and transtentorial herniation. CT, computed tomography; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage.

A. CT brain.

1. Consider LP and MRI, if head CT is normal, depending on interval from onset.

2. CT is more than 95% sensitive for SAH within 24 hours but rapidly decreases thereafter. CSF xanthochromia can take 12 hours to develop and distinguishing traumatic LP from SAH within 12 hours can be difficult.

3. MRI is highly sensitive for subacute SAH and can reveal alternate diagnosis for thunderclap headache.

B. Neurosurgery and neuroendovascular consultation (clipping versus coiling)

C. Emergent CSF diversion with ventriculostomy if obstructive hydrocephalus present

1. Vascular imaging with CTA or four-vessel catheter angiography followed by aneurysm treatment within 24 hours

a. If renal insufficiency.

(1) Normal saline 1 mL/kg/hour before and after angiography.

(2) Consider acetylcysteine 600 mg enteral twice daily for 2 days.

D. Maintain normotension for unsecured aneurysm. Nicardipine and labetalol are preferred. Induced hypertension after aneurysm treatment may be necessary if delayed ischemic neurologic deficit develops.

E. Avoid hypotension and hypovolemia.

F. Enteral nimodipine 60 mg every 4 hours or 30 mg every 2 hours for 21 days if tolerated

G. Frequent neurologic assessments, analgesics, and stool softeners

H. AED if seizures occur.

I. Manage elevated ICP if present.

J. VTE prophylaxis.

1. Pneumatic compression devices

2. Consider SQ unfractionated heparin (UFH) 5,000 units every 8 or 12 hours, 24 hours after aneurysm secured.

K. Manage complications such as rebleeding, vasospasm, delayed cerebral ischemia, respiratory failure, cardiomyopathy, dysrhythmias, fevers, and hyponatremia.

1. Antifibrinolytic therapy (epsilon aminocaproic acid or tranexamic acid) reduces risk of rebleeding but increases risk of cerebral ischemia and is reasonable if immediate aneurysm treatment not feasible.

CEREBELLAR HEMORRHAGE

A. ABCs. Airway, breathing, and circulation

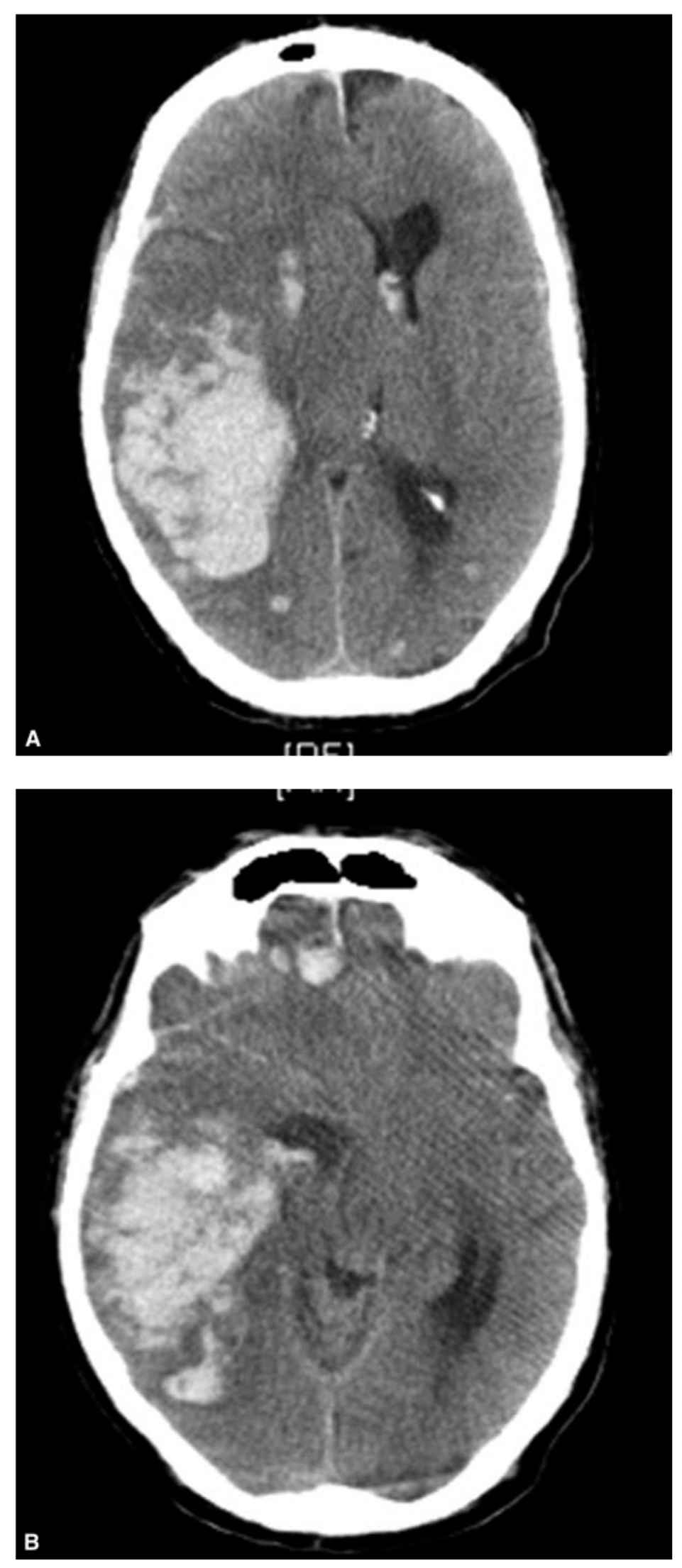

B. Consider neurosurgery consultation (Figs. 63.8 and 63.9).

C. Emergent craniotomy with hematoma removal in patients with neurologic deterioration, brainstem compression, or obstructive hydrocephalus

D. Ventriculostomy placement for obstructive hydrocephalus may precipitate upward herniation. Recommend as an adjunct to surgical decompression.

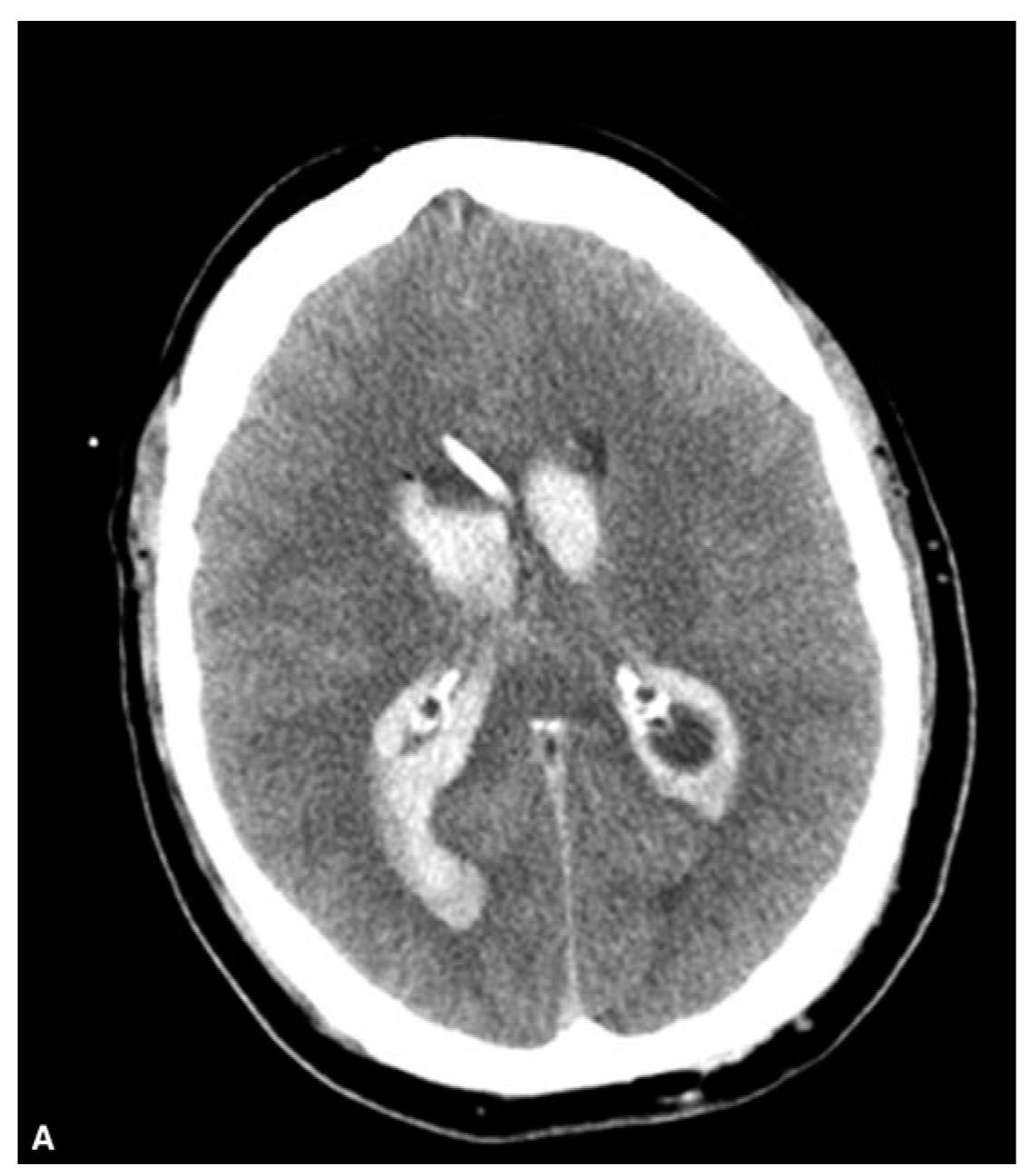

INTRACEREBRAL HEMORRHAGE AND INTRAVENTRICULAR HEMORRHAGE

A. Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) represents 10% to 12% of all strokes.

B. Deep ICH (basal ganglia, thalamus, pons, and cerebellum) is commonly due to chronic hypertension.

C. Lobar ICH in elderly patients is commonly due to cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

D. ICH growth can occur within the first 6 hours.

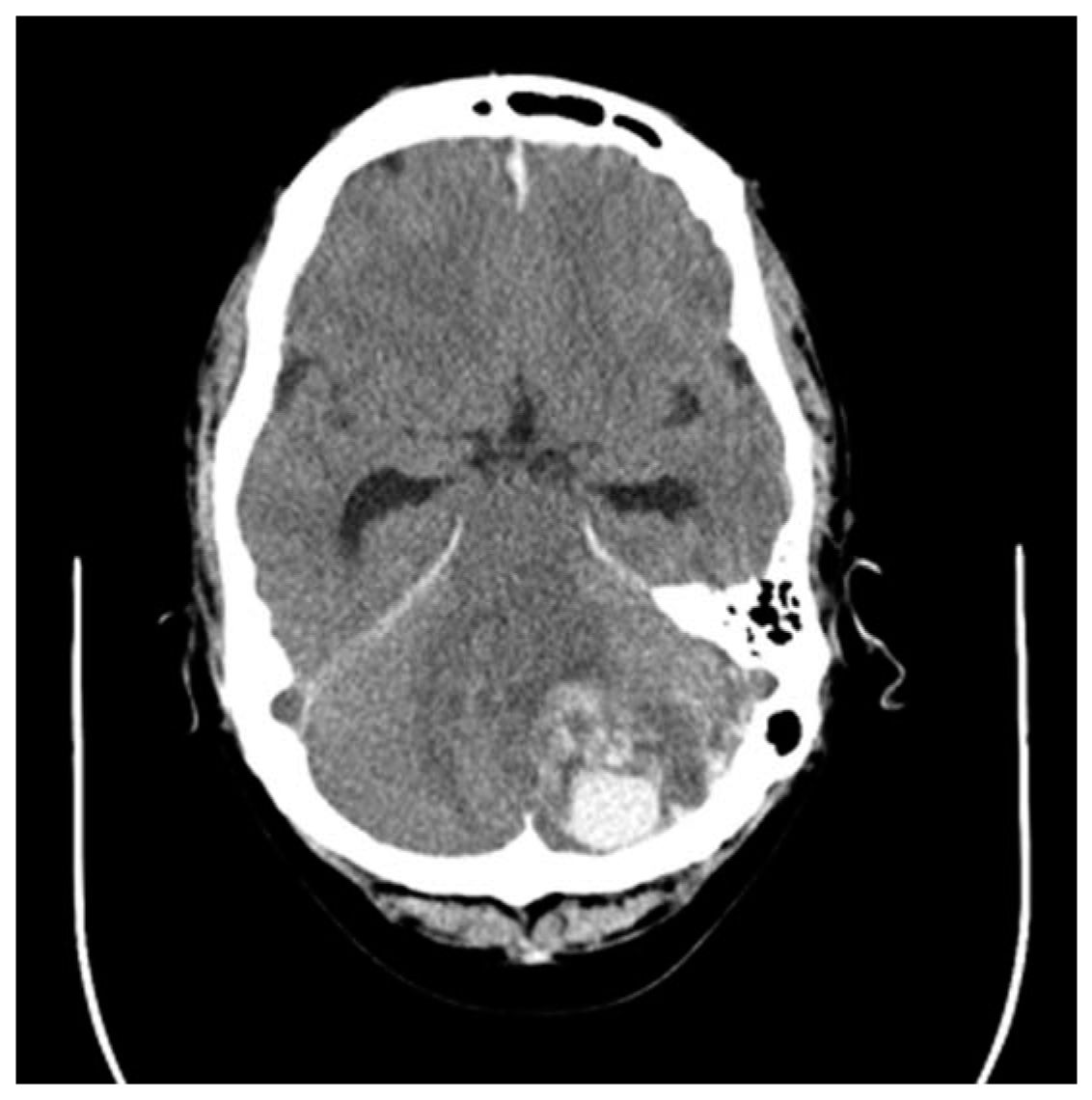

E. Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) occurs in 40% of primary ICH and 15% of aneurysmal SAH (Fig. 63.10).

F. IVH with or without hydrocephalus is a predictor of poor outcome. Estimated 30-day mortality is 40% to 80%.

G. IVH can result in elevated ICP, decreased CPP, and if severe, herniation and death.

H. Intubate for depressed level of consciousness.

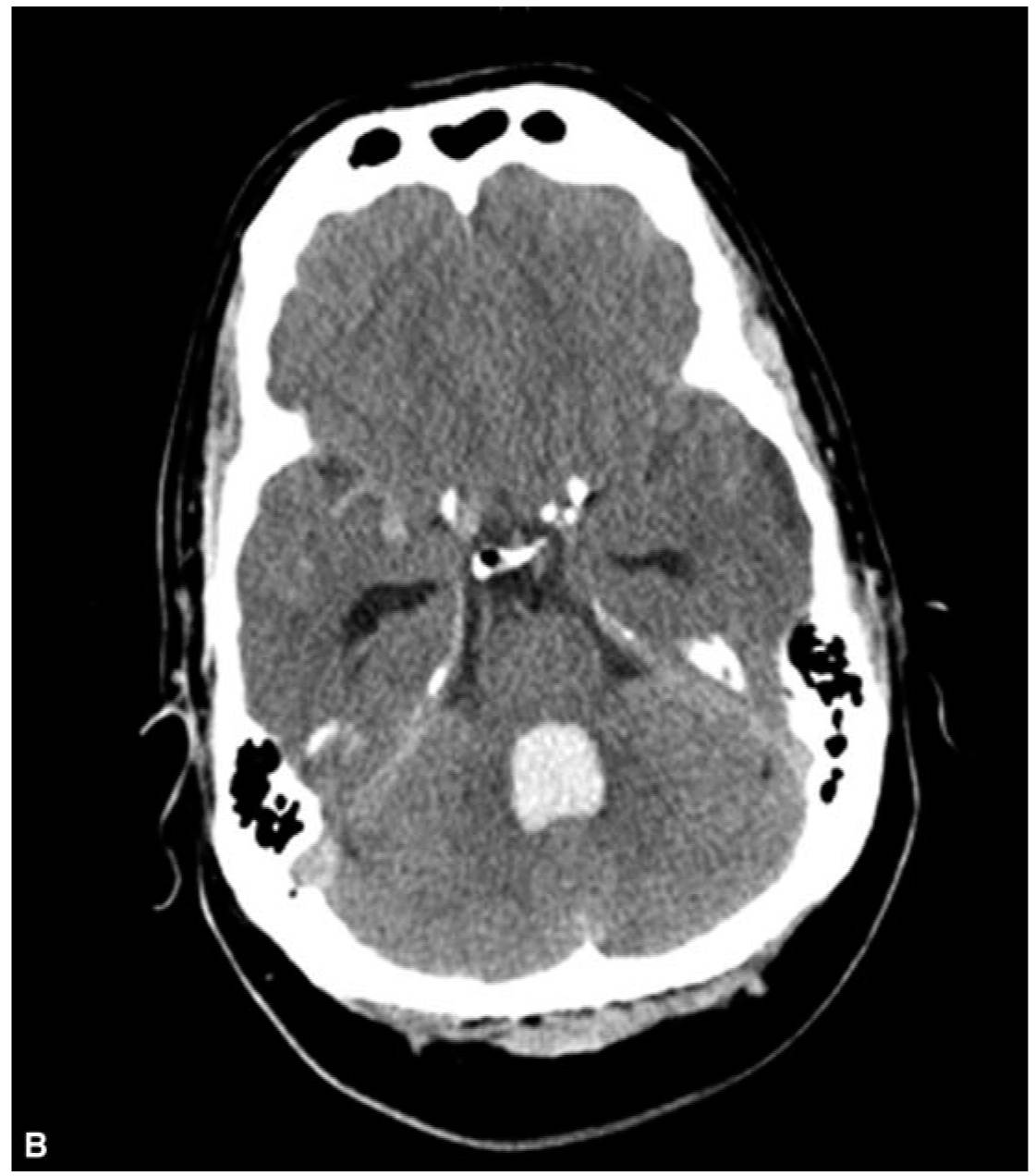

FIGURE 63.8 CT head without contrast demonstrates acute intraparenchymal hemorrhage of the left cerebellar hemisphere with effacement of the fourth ventricle and subsequent hydrocephalus of the third and lateral ventricles. The patient underwent placement of a right frontal ventriculostomy and a suboccipital craniectomy with bilateral decompression and removal of intracerebellar clot. CT, computed tomography.

FIGURE 63.9 CT brain without contrast. Left cerebellar hemorrhage with mass effect and effacement of the fourth ventricle and resulting obstructive hydrocephalus. CT, computed tomography.

FIGURE 63.10 CT brain without contrast. Primary IVH with obstructive hydrocephalus. CT, computed tomography; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage.

I. Ventriculostomy placement for patients with obstructive hydrocephalus. Check PT/INR, aPTT, and platelet count. Correct coagulopathy prior to ventriculostomy placement (see sections Malignant Cerebral Edema, Management of Intracranial Bleeding After Thrombolytic Therapy, and Management of Intracranial Bleeding with Warfin).

J. ICP control (see section Elevated Intracranial Pressure) if elevated despite CSF diversion

K. Consider additional brain (e.g., MRI) and vascular imaging to assess for bleeding source.

L. The efficacy of intraventricular tPA for clot lysis is uncertain but appears safe and may be reasonable in selected circumstances. Clinical trials are ongoing.

1. Avoid in setting of unsecured aneurysms, vascular malformations, clotting disorders, hemorrhage instability, and within 48 hours of craniotomy.

2. Consider if IVH involves greater than 30% of one of the lateral ventricles and/or the third or fourth ventricle and impaired consciousness.

3. Dosing. 1 mg every 8 hours up to 12 doses or clearance of IVH from third and fourth ventricle.

4. Administration. Withdraw CSF volume equivalent to volume of alteplase to be administered followed by 1 to 1.5 mL preservative-free saline flush.

5. Clamp ventricular catheter for 2 hours. Unclamp if ICP rises above 25 mm Hg and drain 2 cc of CSF. Reclamp if ICP normalizes.

M. BP control. SBP below 140 mm Hg is safe and reasonable for ICH although no data support a target BP for isolated IVH.

N. Avoid hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia; treat fever; and initiate VTE prophylaxis within 48 hours of ICH/IVH stability.

O. AED for seizures. Prophylactic AED not recommended. Consider continuous EEG monitoring for patients with impaired consciousness out of proportion to anatomic injury.

P. Surgical evacuation for non-life-threatening ICH is not routinely recommended.

METASTATIC EPIDURAL SPINAL CORD COMPRESSION

A. Emergent gadolinium-enhanced MRI of the spine

B. If MRI not feasible—CT myelography

C. Dexamethasone. Optimal dose uncertain. Boluses 16 to 100 mg IV have been used followed by 4 mg IV every 6 hours. Higher doses are not proven to be more effective and can lead to GI bleeding or perforation, psychosis, or sepsis.

D. Consider urgent radiation therapy within 24 hours.

E. Consider chemotherapy for chemosensitive tumors.

F. Consider surgical intervention.

1. If worsening deficits during or following radiotherapy

2. If radiation-resistant tumor

3. If spinal instability, laminectomy is not recommended as it may destabilize spine.

G. Pain control with opioids

H. VTE prophylaxis

I. Bowel regimen.

SPINAL CORD INJURY

A. Central cord syndrome is the most common form of incomplete spinal cord injury (SCI).

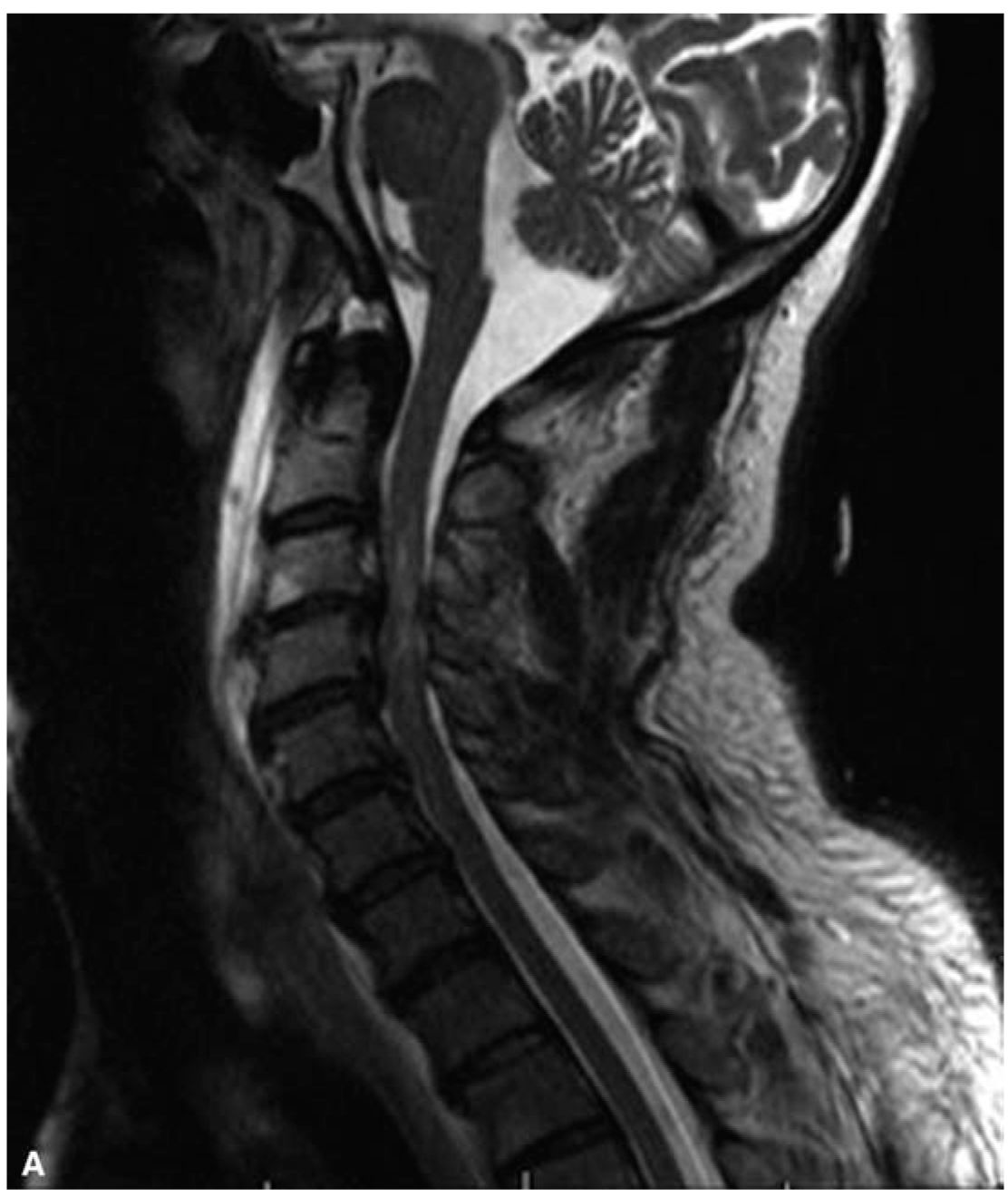

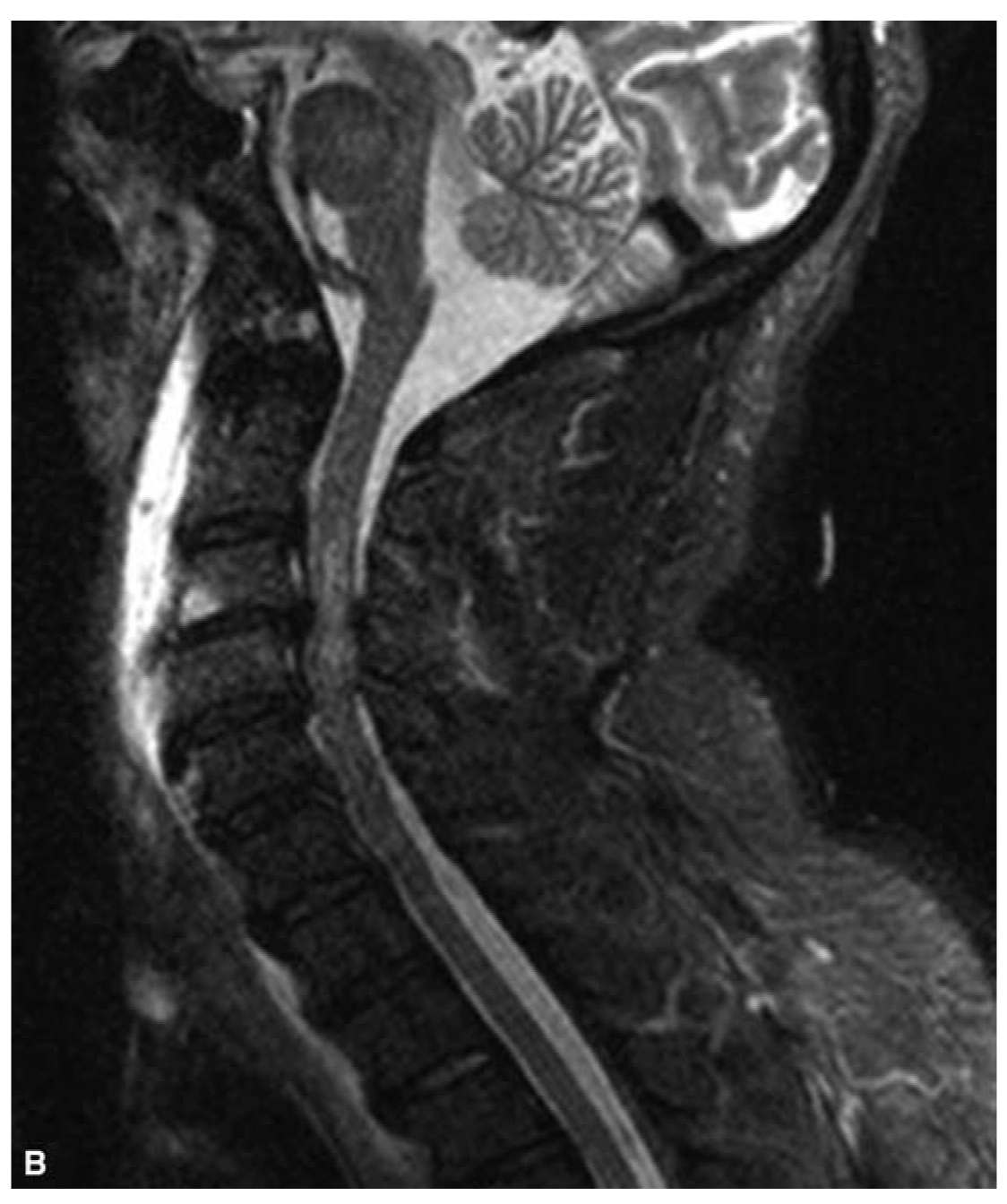

1. Traumatic hyperextension in patients with long-standing cervical spondylosis is the most frequent etiology (Fig. 63.11).

FIGURE 63.11 MRI cervical spine: T2-weighted sagittal image. C3–C4, C4–C5 disc herniations associated with underlying mild cervical canal stenosis causing spinal cord compression in a patient with central cord syndrome. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

2. Other associations.

a. Cervical spine fracture dislocations

b. Congenital or acquired cervical canal stenosis

c. Central spinal cord bleeding

3. Disproportionate upper motor neuron pattern of weakness. Upper limbs are more affected than lower limbs.

4. Muscle stretch reflexes are initially absent.

5. Bladder dysfunction is common.

6. Variable sensory loss below injury level

7. Surgery is rarely indicated.

8. Favorable prognosis in patients younger than 70 years without comorbidities

B. Other SCI. Transverse myelitis, Brown-Séquard (hemicord) syndrome, anterior spinal artery syndrome, posterior cord syndrome

C. Airway management for high cervical injury

D. Fluid resuscitation and vasopressor support with dopamine for neurogenic shock

E. Consider maintaining MAP above 85 mm Hg for the first 7 days.

F. Corticosteroids are not recommended by SCI guidelines.

1. No class I or II evidence supporting clinical benefit of high-dose IVMP.

2. High-dose IVMP associated with harmful side effects including wound infections, hyperglycemia, GI bleeding, myopathy, and increased mortality independent of injury severity

G. Utility of hypothermia is uncertain.

H. Initiate VTE prophylaxis within 72 hours and continue for at least 3 months.

1. Low-molecular-weight heparin

2. Low-dose SQ UFH plus electrical stimulation or pneumatic compression boots

3. Low-dose heparin or oral anticoagulation alone is not recommended (level II).

4. Inferior vena cava filters are not recommended unless a patient has a contraindication to or fails pharmacologic prophylaxis.

5. GI prophylaxis with proton-pump inhibitor or H2 blocker.

ACUTE CAUDA EQUINA SYNDROME

A. Emergent gadolinium-enhanced MRI lumbosacral spine

B. Bladder catheterization for urinary retention. Check serial post–void urinary residual if catheter has not been placed.

C. Analgesics, muscle relaxants (e.g., diazepam, baclofen)

D. Early surgical decompression within 24 hours

E. Radiation/chemotherapy for neoplastic etiologies

F. Intravenous steroids can be used for metastatic etiologies but otherwise have not been shown to improve outcome.

G. Physical and occupational therapy

H. Bowel regimen

A. Occurs in up to 70% after SCI typically within 4 months and in those with injury above the sixth thoracic level. Commonly follows acute spinal shock.

B. Clinical features include SBP change by 20% or greater associated with change in pulse, sweating and piloerection above the injury level, facial flushing, headache, visual changes, anxiety, nausea, and nasal congestion. It can lead to posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, ICH, SAH, seizures, arrhythmia, pulmonary edema, retinal bleeding, coma, and death if untreated.

C. Nonpharmacologic management.

1. Place patient in an upright position with legs lowered.

2. Avoid constrictive garments or devices.

3. Minimize precipitating stimuli including noxious stimuli below the injury level, bladder distention, bowel impaction, pressure ulcers, infection, urologic and endoscopic procedures, sympathomimetic agents, and sildenafil citrate.

D. Pharmacologic management if nonpharmacologic measures fail and SBP above 150 mm Hg. Utilize antihypertensive with rapid onset and short duration. Calcium-channel blockers, ACEIs, and nitrates are commonly used.

GUILLAIN–BARRÉ SYNDROME

A. Clinical features. Ascending areflexic weakness is common. Respiratory and bulbar muscles are frequently involved. Objective sensory loss is typically absent but lower extremity radicular distribution paresthesias/dysesthesias are commonly reported.

B. Workup.

1. Nerve conduction studies including F waves

2. CSF for albuminocytologic dissociation

C. Management.

1. Endotracheal intubation if forced vital capacity (FVC) less than 15 mL/kg and/or negative inspiratory force (NIF) weaker than -25 cm H2O

2. Monitor for autonomic disturbances.

3. Plasma exchange (PLEX) 200 to 250 mL/kg for 5 exchanges over 1 to 2 weeks or intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) 0.4 g/kg IV per day for 5 days.

MYASTHENIC CRISIS

A. Clinical features. Fatigable weakness. Ocular, bulbar, and respiratory muscles are frequently involved.

B. Workup.

1. Neurophysiologic studies. Repetitive stimulation, single-fiber electromyography

2. Serum acetylcholine receptor antibodies

3. Edrophonium testing is not commonly performed for safety concerns.

C. Management.

1. Closely monitor motor weakness, bulbar weakness, and respiration.

2. Initiate noninvasive ventilation early. Intubate and mechanically ventilate when FVC is less than 15 mL/kg and/or NIF is < 25 cm H2O or there is difficulty controlling secretions. Interpret VC and NIF with caution as poor oral seal on spirometer can adversely affect readings. Continuous end-tidal capnography may be useful.

3. Assess for cholinergic signs and symptoms. Discontinue anticholinesterase if there is any concern for cholinergic toxicity.

4. Avoid all drugs with anticholinergic properties.

5. Manage concurrent infections.

6. Administer PLEX every other day for 5 or more sessions depending on response or IVIG 0.4 g/kg IV daily for 5 days.

7. Consider adjunctive immunosuppression.

8. Monitor closely when initiating corticosteroids as early deterioration can occur. It is less of a concern if initiating concomitantly with PLEX or IVIG.

A. Stop causative agent.

B. Diphenhydramine 50 mg IV.

C. Benztropine 2 mg IV.

D. Typically follow with oral anticholinergic agents such as benztropine 1 to 2 mg twice daily for 1 to 2 weeks, especially if due to long-acting dopamine receptor blocking agent.

NEUROLEPTIC MALIGNANT SYNDROME

A. Clinical features. Hyperthermia, rigidity, altered mental status, dysautonomia, elevated creatine kinase and transaminases and leukocytosis.

B. Management.

1. Immediately withdraw neuroleptics or dopamine-depleting agents or reinstitute previously withdrawn dopaminergic therapy.

2. Hydrate and maintain adequate urine flow.

3. Alkalinize urine if myoglobinuria is present.

4. Lower elevated body temperature.

5. Administer bromocriptine 2.5 to 5 mg four times daily. Increase dose until response occurs (maximum 50 mg daily).

6. Administer dantrolene 1 to 10 mg/kg daily in divided doses.

7. Other possible treatments include amantadine, levodopa, and carbamazepine.

8. If severe psychosis occurs during treatment, consider electroconvulsive therapy.

ACUTE SEROTONIN SYNDROME

A. Clinical features: Similar to neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Adventitial movements such as tremor, chorea, and myoclonus are common.

B. Management.

1. Discontinue serotonergic drugs.

2. Administer benzodiazepines—especially for agitation.

3. Administer cyproheptadine 12 to 32 mg daily. Consider initial dose in adults of 12 mg and maintenance dose of 8 mg every 6 hours.

4. Other possible treatments include propranolol, chlorpromazine, and methysergide (not available in the United States).

5. Monitor for seizures, arrhythmias, rhabdomyolysis, renal injury, hyperthermia, and coagulopathy.

GIANT CELL ARTERITIS (TEMPORAL ARTERITIS)

A. Clinical features. Unilateral or bilateral vision loss, jaw or tongue claudication, scalp tenderness, fever, and malaise.

B. Workup.

1. STAT ESR and CRP

2. Long-segment superficial temporal artery biopsy

C. Management. Initiate empiric oral prednisone 1 to 2 mg/kg daily or methylprednisolone 1 g IV daily for 3 days followed by oral prednisone 1 mg/kg daily, especially if there are visual symptoms or visual loss. Do not wait for biopsy confirmation to start treatment.

CENTRAL RETINAL ARTERY OCCLUSION

A. Four classifications.

1. Non-arteritic permanent central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO), which accounts for 2/3 of all CRAO

2. Non-arteritic transient CRAO, which accounts for 15% of all CRAO and has the best prognosis

3. Non-arteritic CRAO with cilioretinal sparing

4. Arteritic CRAO (e.g., giant cell arteritis), which accounts for <5% of all CRAO.

B. Management.

1. No consensus.

2. Treat hypertension, hyperglycemia, and hyperlipidemia. Avoid tobacco use.

3. Pharmacologic treatment:

a. Vasodilators. Pentoxyphylline, sublingual isosorbide dinitrite, hyperbaric oxygen, inhalation of carbogen, calcium-channel blockers, retrobulbar injection of papaverine or tolazoline, prostaglandin E1, CO2 rebreathing, atropine, acetylcholine, lidocaine hydrochloride.

b. Mannitol 1.5 to 2 g/ kg IV over 30 to 60 minutes

c. Acetazolamide 250 to 500 mg IV four times daily for 24 hours

d. IVMP

e. Antiplatelet or anticoagulant agents

f. Topical timolol 0.5% one eye drop in affected eye if elevated intraocular pressure

4. Surgical treatment.

a. Anterior chamber paracentesis

b. Neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser embolectomy

c. Pars plana vitrectomy

5. Ocular massage to dislodge embolus from central retinal artery

6. Hemodilution

7. Thrombolysis is not supported by randomized clinical trials.

WERNICKE’S ENCEPHALOPATHY

A. Thiamine deficiency state associated with chronic alcoholism, hyperemesis gravidarum, starvation, GI malignancies, pyloric stenosis, anorexia nervosa, inappropriate parenteral nutrition, digitalis intoxication, chronic hemodialysis, bariatric surgery, and thyrotoxicosis

B. Clinical features. acute confusion, ataxia, and ocular findings including nystagmus and gaze paresis.

C. Management.

1. Administer thiamine 500 mg IV three times daily for 2 to 3 days. If there is partial response, continue 250 mg parenteral for 5 days.

2. Avoid glucose without thiamine.

PITUITARY TUMOR APOPLEXY

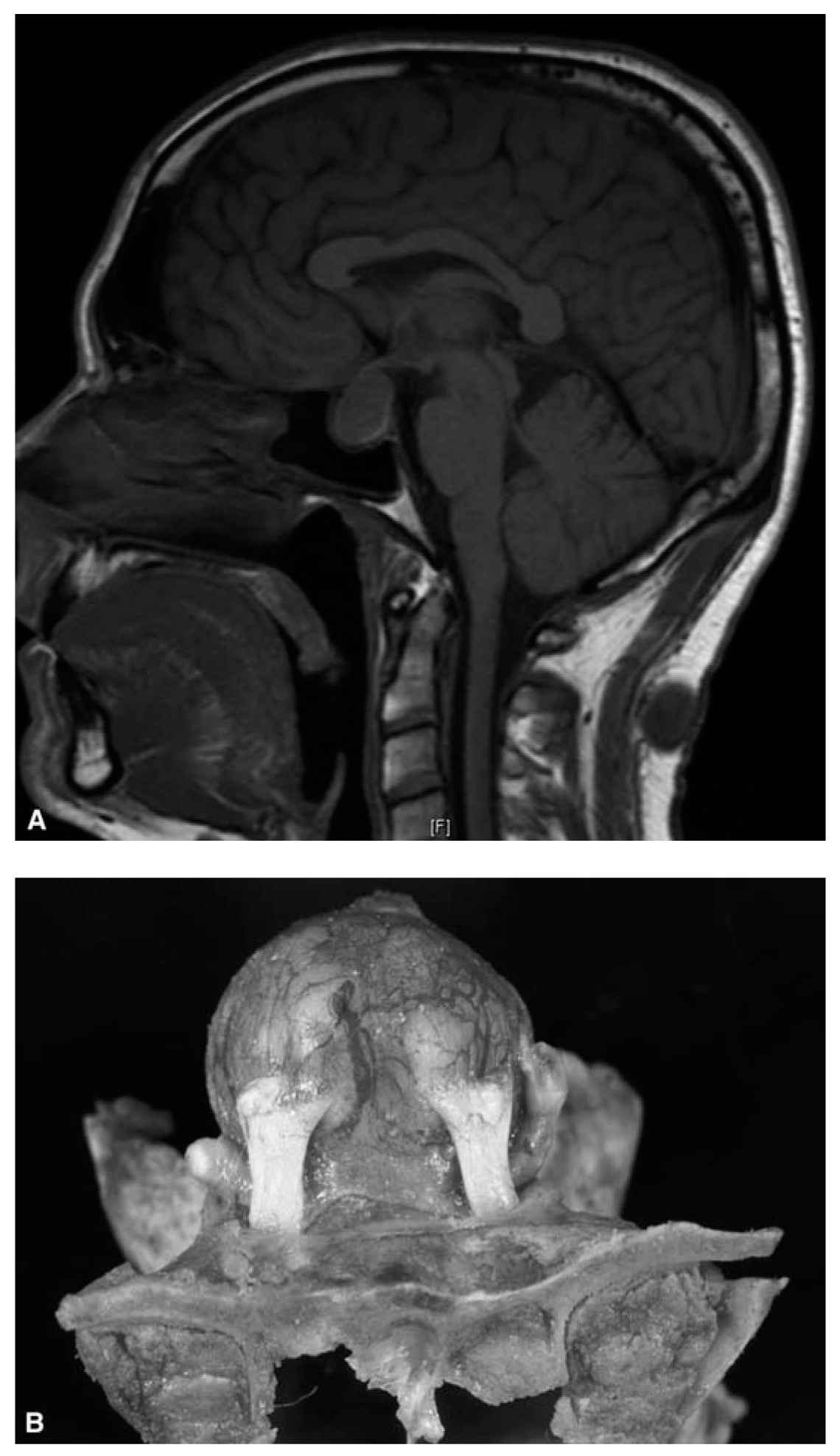

A. Clinical features: Thunderclap headache, diplopia (cranial nerve III, IV, and VI palsies), decreased visual acuity, visual field defects (temporal or bitemporal hemianopsia), impaired consciousness, nausea/vomiting (Fig. 63.12A and B).

B. Precipitating and associated factors. Acute pituitary hemorrhage or infarct, head trauma, hypotension, anticoagulation, dopamine agonist use, pituitary dynamic testing thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GNRH), insulin-induced hypoglycemia), history of hypertension or pituitary irradiation.

C. Workup. STAT MRI brain or pituitary CT scan if MRI cannot be performed.

D. Management.

1. Hemodynamic resuscitation with fluids, vasopressors, and hydrocortisone 200 mg IV once followed by 50 mg IV four times daily or 100 mg IV thrice daily

2. Endocrinology, neurosurgery, ophthalmology consultation

3. Vascular imaging if concern for aneurysm

4. Endocrine assessment. Serum electrolytes, renal function tests, PT (INR), aPTT, CBC, random cortisol, prolactin, free T4, TSH, Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), IGF-1, growth hormone, luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, testosterone in men, estradiol in women

5. Thyroid hormone replacement if deficient

FIGURE 63.12 A: MRI brain demonstrating pituitary apoplexy. B: Pituitary apoplexy. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging. (See color plates.)

6. Indications for empiric steroids:

a. Hemodynamic instability (see Pituitary Tumor Apoplexy)

b. Altered consciousness

c. Reduced visual acuity or severe visual defects

7. Urgent surgical trans-sphenoidal decompression for patients with severe neuro-opthalmologic symptoms if no contraindications. Surgery is optimal when performed within 7 days of onset.

8. Conservative management for patients with absent or mild neuro-opthalmologic symptoms including ocular palsies in the absence of visual field defects or visual acuity deficits, or early improvement of visual symptoms

9. Postoperative management.

a. Check electrolytes, renal function, and plasma and urine osmolality if diabetes insipidus is suspected.

b. Monitor for CSF leak, cortisol deficiency, visual loss, and meningitis.

10. Formal visual field testing when clinically stable.

POSTERIOR REVERSIBLE ENCEPHALOPATHY SYNDROME

A. Clinical features. Headache, visual changes, seizures, nausea/vomiting, and occasional sensorimotor deficits

B. Workup. MRI brain demonstrates posterior hemispheric white matter edema. Typically spares cortex. Can involve cerebellum and brainstem and occasionally frontal lobes. CT if MRI not feasible.

C. Management.

1. Eliminate or treat precipitating causes such as hypertension, immunosuppressant medications, eclampsia, uremia, sepsis, and autoimmune disorders.

2. Administer AED for seizures

3. Treat hypertension. Do not decrease by more than 25% of presenting MAP within the first few hours.

Key Points

• This chapter is intended to serve as a uptodate quick reference guide to an audience composed of healthcare practitioners, including neurologists, neurosurgeons, critical care physicians, emergency medicine physicians, and nurses, involved in the care of neurologic and neurosurgical critically ill patients.

• Algorithms in accord with accepted evidence-based standards, highlighting concise and practical diagnostic testing and management strategies for a comprehensive index of neurologic and neurosurgical emergencies, are provided within this chapter.

• Radiologic images, histologic slides, and video highlighting different disease states discussed within this chapter are also provided, further contributing to a practitioner’s rapid diagnosis and treatment of this patient population.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree