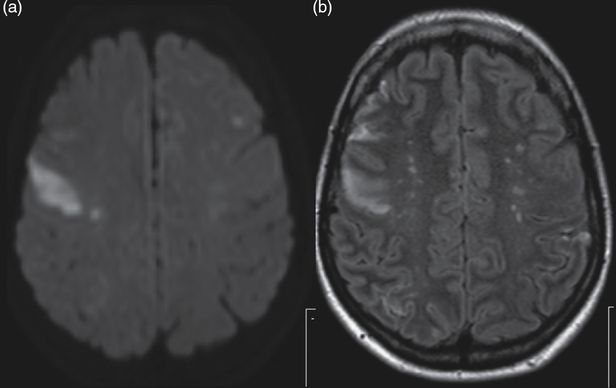

Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. (a) First brain MRI FLAIR axial section showing subcortical parieto-occipital hyperintensities. (b) Angio-MRI showing segmental narrowing of both middle, left anterior and posterior cerebral arteries, and vertebral arteries. (c) Second brain MRI FLAIR axial section, after clinical neurological worsening showing extension of the occipital hyperintensities. (d) Three-month follow-up angio-MRI showing complete resolution of vasoconstriction.

Discussion

This is an illustrative case of a patient with a thunderclap headache where subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) had to be excluded. At the community hospital there were doubts regarding neck stiffness and a traumatic LP was not helpful in excluding bacterial meningitis, so antibiotics were started. Since locally it was not possible to investigate other causes of thunderclap headache (e.g., cerebral venous thrombosis, cervical arterial dissection) the patient was referred to a tertiary hospital.

Headache is one of the most common clinical manifestations of cerebral vasculitis, occurring in up to 63% of patients with PCNSV [6,7]. Altered cognition, hemiparesis, and visual symptoms are also frequently reported. Typically headaches in PCNSV are progressive [5,8,9]. A significant number of patients with suspected PCNSV will have headache and other focal neurological signs caused by vasospasm instead of vasculitis of the cerebral vessels [8]. In fact, some of the earliest series of PCNSV included a subgroup named benign angiopathy of the CNS, which is currently considered to be a vasoconstriction syndrome [10,11]. Distinguishing RCVS from PCNSV is crucial, since treatment options are completely different. However, misdiagnosis is not infrequent and leads to unnecessary invasive diagnostic procedures or exposure of patients to immunosuppressive treatments [12]. Patients with RCVS usually present with sudden (peaking in <1 minute) onset of severe headache (thunderclap headache) that, as in the present case, warrants exclusion of SAH. When there are several typical episodes of thunderclap headache, as in this patient, RCVS is a most probable diagnosis [13].

CSF is usually unremarkable in RCVS whereas it is abnormal in 80–90% of patients with cerebral vasculitis [14]. In the present case a traumatic LP initially confused the diagnosis. In patients with PCNSV, CSF pleocytosis rarely exceeds 250 cells/μL and the presence of CSF leukocytosis greater than 250 cells/μL, along with a white blood cell differential showing increased polymorphonuclear rather than lymphocytic cell count, should be a red flag leading to an aggressive search for infection [8].

Several conditions and substances have been associated to RCVS. Therefore it is very important to review all the medications that the patient is using, including over-the-counter substances [13,15]. Typically the patient has been exposed to vasoactive substances, such as etilefrine, the sympathomimetic recently prescribed to this patient, immunosuppressant or blood products, etc. RCVS may be associated with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) [16]. Acute headache, confusion, seizures, and cortical blindness associated with a characteristic MR imaging pattern with FLAIR bilateral symmetrical hemispheric junctional/boundary high signal in the cortex, subcortical and deep white matter, particularly in the parietal and occipital regions but that may also involve the frontal areas as in our patient [17]. Segmental vasoconstriction of cerebral arteries demonstrated by angiography (magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), computed tomography angiography (CTA), or catheter angiography) is the key feature of RCVS and is at times difficult to distinguish from PCNSV. However, irregular and asymmetrical arterial stenosis and multiple occlusions suggest PCNSV rather than RCVS [11,13,18]. Finally, to make a definite diagnosis it is crucial to demonstrate the reversibility of the angiographic changes in a follow-up angiogram [14]. TCD is also very useful for monitoring temporal evolution of cerebral vasoconstriction [19].

RCVS treatment with fluids and nimodipine is still empirical. Avoiding exposure to predisposing substances is very important. Cerebral ischemia can occur in 6–9% of the patients, usually in the second week. Long-term recurrences are rare [14].

Pitfall and tips

Both RCVS and PCNSV are associated with headache, focal neurological signs, and segmental cerebral vessel constriction. Headache pattern, predisposing causes, and typical imaging features help to distinguish RCVS from PCNSV. Headache is usually acute (not progressive) and intense (“the worst headache ever”) in RCVS. Thorough review of exposure to medications or drugs that may cause vasoconstriction is very important. RCVS may be associated with typical features of PRES on brain MRI.

Case 2. Does this young woman with multifocal ischemic strokes have cerebral vasculitis? A case of non-infectious endocarditis

Case description

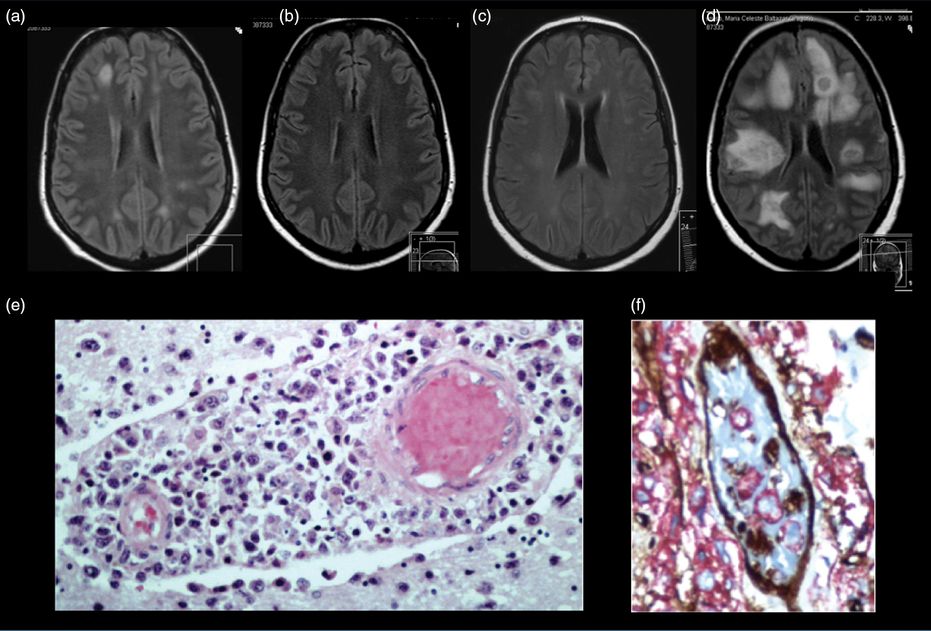

A 41-year-old woman, with smoking habits and a previous history, 4 months before admission, of right lower limb deep vein thrombosis (DVT), was admitted due to sudden onset of left facial and left arm weakness. She had recent weight loss (8 kg in 3 months) and typical features of Raynaud syndrome. One month prior to admission she complained of fever, thoracic pain, and myalgia and after common infections were excluded, she was referred to the Rheumatology outpatient clinic. Examination disclosed a subungual purpuric lesion of the second digit of the left hand, a central left facial paresis, and a slight drift of the left upper limb. Brain MRI showed acute ischemic lesions in the right MCA, left MCA, the left posterior cerebral artery (PCA) territory, and the left anterior-inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) territory, as well as multiple subacute bihemispheric ischemic lesions (Figure 11.2). On angio-MRI there was no flow in the distal cortical right MCA branches and in the P3 and P4 segments of the left PCA, and a distal small left internal carotid artery aneurysmatic dilatation.

Non-infective endocarditis. Brain MRI, axial sections. (a) Diffusion-weighted image and (b) FLAIR showing right prefrontal (with correspondent hypointensity in the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map) and left frontal hyperintensities (isointense in the ADC map) suggesting, respectively, acute and non-recent ischemic lesions in the territory of both middle cerebral arteries.

Cerebral infarcts in different territories and signs and symptoms of systemic disease indicate the following diagnostic hypotheses: (1) autoimmune connective tissue disorder (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE); primary systemic vasculitis) with cerebral involvement (associated with vasculitis or prothrombotic autoantibodies); or (2) cardioembolism from infective endocarditis/non-infective endocarditis/atrial myxoma.

Laboratory work-up revealed leukocytosis (13 800 leukocytes and 78% neutrophils with normal CRP and procalcitonin). Antinuclear (ANA) antibodies, anti-double-stranded (ds-DNA) antibodies, anti-Sjögren’s syndrome-related antigen A (anti-Ro/SSA) and anti-Sjögren’s-syndrome-related antigen B (anti-La/SSB) antibodies, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) antibodies, lupus anticoagulant (LA), and antiphospholipid (AP) antibodies and cryoglobulins were negative. Blood cultures and comprehensive infection screening were negative. CSF examination was unremarkable. Dermatological evaluation of the finger lesion pointed to a nailfold small infarct and biopsy only showed nonspecific changes (no signs of vasculitis). Retinal angiography was unremarkable. She had a normal ECG. Transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) disclosed mitral valve vegetations with moderate mitral valve regurgitation and an aortic valve vegetation. A thoraco-abdominal-pelvic CT disclosed distal bilateral pulmonary embolism. Initial empirical treatment for infective endocarditis with intravenous ceftriaxone 2 g/day was started, until infectious work-up was completed. At this point the diagnosis of non-infective endocarditis was made and full dose anticoagulation started.

Discussion

One important differential diagnosis of cerebral vasculitis is endocarditis, particularly infective endocarditis, because both conditions may present with similar clinical (multiple strokes, encephalopathy) and ancillary findings (multivessel narrowing and aneurysmatic dilations) [20]. Differentiating these two entities is extremely important because treatment is completely different and exposing a patient with infective endocarditis to immunosuppressive agents, such as cyclophosphamide, may have catastrophic consequences.

Cerebral ischemia in several arterial territories, which was documented in this patient, is a frequent finding in patients with cerebral vasculitis [6,21]. Our patient had a small carotid artery aneurysmatic dilation and multiple vessel occlusions. This pattern, though not typical, could occur in a patient with cerebral vasculitis. However, multifocal cerebral ischemia is also a key feature of cardioembolic stroke and of prothrombotic disorders such as the antiphospholipid syndrome and others.

In this patient there were clear symptoms and signs (fever, myalgias, skin lesions, weight loss) pointing to a systemic disease with CNS involvement. The main question was whether the cerebral ischemia was related to secondary cerebral vasculitis (related to a systemic disease) or to cardioembolism.

Infective endocarditis and cerebral vasculitis (primary or secondary) are associated with elevated inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), CRP). CSF is usually abnormal in cerebral vasculitis (elevated CSF protein content, positive oligoclonal bands, elevated leukocyte count) [8]. In contrast, CSF examination is less frequently abnormal in infective endocarditis, but some cases with CSF pleocytosis have been reported [20]. Thus, these markers are not really helpful in distinguishing these two conditions. TEE is essential for the diagnosis of endocarditis. TEE disclosed valvular vegetations in our patient. The occurrence of a previous DVT and negative inflammatory markers, such and CRP and procalcitonin, as well as complete negative infectious work-up, pointed to a non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE), associated with either an autoimmune disorder (e.g., Libman–Sacks endocarditis in SLE) or, as in our patient, a tumor.

Pitfalls and tip

Cerebral vasculitis (primary or secondary) and endocarditis (infective or non-infective) may present with multifocal cerebral ischemia. Also, bacterial endocarditis can be associated with cerebral vessel changes with multifocal stenosis and aneurysmatic dilations. TEE should be included in the diagnostic work-up of patients with suspected cerebral vasculitis, whenever a cardioembolic source of embolism has to be excluded.

Case 3. Does this young woman with seizures, raised inflammatory serological markers, and multifocal CNS white matter changes have cerebral vasculitis? A case of cerebral lymphoma

Case description

A 47-year-old previously healthy woman was admitted to the internal medicine ward because of unremitting fever, anemia, and raised inflammatory markers (ESR 110 mm/s, CRP 23 mg/dL). An extensive work-up had excluded infection. Thoraco-abdomino-pelvic CT, PET-CT, and myelogram were unremarkable. Neurological consultation was requested due to complex partial seizures. After recovering from the seizures, her physical examination was unremarkable. Brain MRI showed multiple subcortical fuzzy hyperintense lesions on FLAIR sequences, the largest one with slight contrast enhancement in the right temporal lobe suggesting demyelinating areas. No changes in cerebral angio-MRI were found (Figure 11.3a). CSF examination showed a protein content of 117 mg/mL and six normal lymphocytic cells. Infectious work-up was unremarkable. At this point, the hypothesis of cerebral vasculitis was raised. Brain biopsy was proposed but the patient refused this procedure. Seizures resolved with antiepileptic medication and there was an improvement of white matter changes with high dose corticosteroids. However, one week later, she had persistent fevers, new spleen enlargement, and serum ferritin elevation (>10 000 ng/mL). Spleen biopsy was performed and pathological examination demonstrated hemophagocytosis. The diagnosis of acquired adult hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with CNS involvement was made and the HLH-94 chemotherapy protocol was started together with steroids. Her symptoms improved as did the white matter lesions after one week (Figure 11.3b) and at 3-month follow-up with brain MRI studies (Figure 11.3c). Two months after completion of the HLH-94 protocol induction phase she was readmitted with somnolence, disorientation, and visual hallucinations. Brain MRI showed a severe recrudescence of supratentorial white matter lesions (Figure 11.3d). Her clinical status rapidly deteriorated with coma and death related to diffuse brain edema. Postmortem pathology was consistent with an intravascular lymphoma identified in the kidney and lungs and CNS diffuse large B-cell monoclonal lymphoma (Figure 11.3e and f).

Brain lymphoma. (a) The first brain MRI showed multiple subcortical fuzzy lesions hyperintense in FLAIR sequence, suggesting demyelinating areas. (b) Brain MRI 1 week and (c) 3 months after steroid treatment showing disappearance of some previously observed lesions and fading of others. (d) Brain MRI after clinical worsening showing multiple hyperintense white matter lesions. (e) Brain pathological examination (hematoxylin and eosin 200×) showing a monoclonal large and immature B-lymphocytic infiltrate. (f) Lung pathological examination (immunohistochemistry anti CD-20) – showing a perivascular and intravascular monoclonal B-lymphocyte infiltrate.

Discussion

Cerebral lymphomas should be included in the differential diagnosis of PCNSV. Intravascular lymphoma can mimic both clinical and radiological features of PCNSV. Constitutional symptoms such as fever, malaise, weight loss, and arthralgias are common in intravascular lymphoma and other lymphomas but are less common in PCNSV. Acute-phase reactants are typically markedly elevated in intravascular lymphoma, but these tend to be normal in PCNSV; and the CSF is usually abnormal in PCNSV but cannot really differentiate it from intravascular lymphoma. Cerebral angiography can be normal in PCNSV, particularly if only small vessels are affected [22]. Hodgkin lymphoma has been associated with granulomatous angiitis of the CNS. Rarely cerebral vasculitis can be the first manifestation of Hodgkin lymphoma [23–25].

CNS biopsy is very important in the diagnosis of PCNSV, since alternative diagnoses can be made in 39% of cases of suspected PCNSV [26]. The sensitivity of brain biopsy for diagnosing PCNSV varies between 50% and 80%, and in most reports brain biopsy has had a morbidity of about 2%, with a negligible mortality when done by an experienced neurosurgeon [27,28]. Cerebral biopsy is particularly important in the differential diagnosis of cerebral vasculitis involving the small cerebral vessels, usually presenting with brain MRI abnormalities and normal cerebral angiograms. Intravascular lymphoma is an extremely rare B-cell lymphoma with a dismal prognosis, involving the CNS in around 34% of the cases and with a known association with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis [29]. Demonstrating a monoclonal B-cell cerebral/vessel infiltration by a cerebral biopsy is the only way to make a definitive diagnosis, in patients presenting initially only with CNS symptoms and no evidence of systemic involvement.

Case 4. Does this 63-year-old man with headaches, memory loss, and photopsias have cerebral vasculitis? A case of cerebral inflammatory amyloid angiopathy

Case description

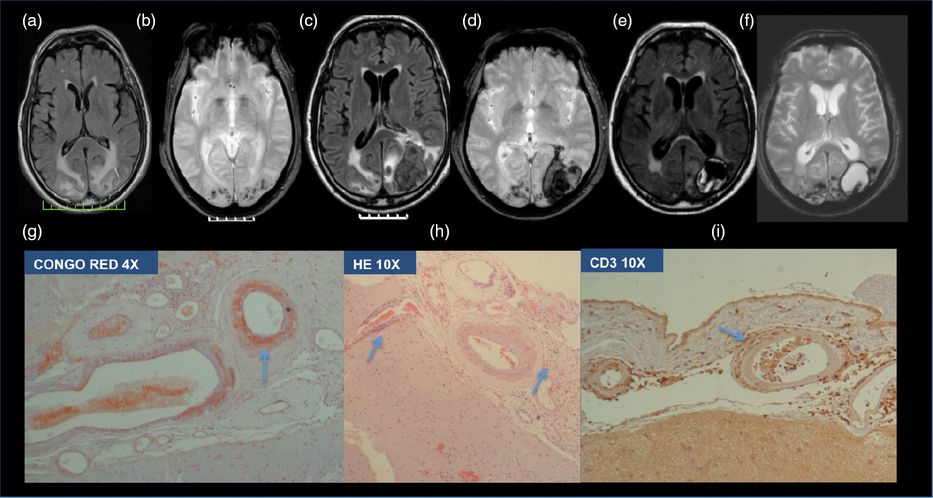

A 63-year-old hypertensive and diabetic man, with a past medical history of myocardial infarction on antiplatelet treatment, had a 2-month history of left parietal headaches and mild memory deficits, and complained of photopsias in the previous week. On examination blood pressure was 200/100 mmHg. There was a slight dysmetria in the right upper limb. Brain MRI disclosed cortico-subcortical bilateral temporo-occipital FLAIR hyperintensities (Figure 11.4a), suggestive of vasogenic edema, multiple microbleeds on T2* sequence (Figure 11.4b), and discrete left cortical occipital enhancement after gadolinium injection. Laboratory work-up, including CSF analysis, transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE), cervical vessel ultrasonography, and TCD were unremarkable. No epileptiform discharges were detected on EEG. Blood pressure was controlled, valproic acid was started, and the patient was discharged home with no further symptoms. However, 3 days later the patient was readmitted due to headache recurrence, psychomotor slowing, and disorientation. On neurologic examination there was a right homonymous hemianopsia and optic ataxia in the right visual field. Brain CT disclosed a left temporo-occipital hematoma. On a repeat brain MRI, in addition to the lobar hematoma and vasogenic edema, no new lesions were identified (Figure 11.4c and d). Conventional cerebral angiography was unremarkable. At this point the diagnosis of a possible inflammatory type of cerebral amyloid angiopathy (ICAA) was raised and a brain biopsy was performed. On pathological examination there was leptomeningeal thickening with amyloid deposition in meningeal vessels and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, with CD3 predominance, supporting ICAA diagnosis (Figure 11.4g, h, and i). In this context intravenous methylprednisolone 1 g/day for 5 days, followed by prednisone 1 mg/kg per day was prescribed with clear clinical improvement. Two months later, after an attempt at lowering the steroid dose, there was a clinical worsening with cognitive impairment and aggressive behavior and agitation. Intravenous cyclophosphamide (0.6 g/m2, monthly for 6 months) was prescribed and the patient stabilized with residual memory deficits. On 6-month follow-up brain MRI no new lesions were found (Figure 11.4e and f).

Inflammatory cerebral amyloid angiopathy. (a) The first brain MRI showing parieto-occipital FLAIR hyperintensities suggestive of vasogenic edema and (b) T2* microbleeds. (c) Second brain MRI, after clinical worsening, showing a left occipital lobar hematoma in FLAIR, and (d) T * sequences. (e) Follow-up FLAIR and (f) T2* brain MRI showing the sequelae of the left occipital hematoma but no new lesions. On pathological examination there was (g) leptomeningeal thickening with amyloid deposition in meningeal vessels in Congo Red, (h) hematoxylin–eosin colorations, and (i) perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, with CD3 predominance in immunohistochemistry studies.

Discussion

Lobar intracerebral hemorrhage is the most frequently recognized clinical manifestation of CAA. In a subset of patients with amyloid beta (Ab) vascular deposition, vascular inflammation is also present. Such patients often present with findings of subacute cognitive decline, seizures, headaches, and T2-hyperintense lesions, and respond to immunosuppressive treatment [30,31]. Two pathologic subtypes have been described: one with a perivascular non-destructive inflammatory infiltration, so-called CAA-related inflammation (CAA-RI), and the second with a vasculitic transmural, often granulomatous, inflammatory infiltrate (Ab-related angiitis or ABRA) [30,32–34]. It has been proposed that ABRA is more closely related to PCNSV than to CAA without inflammatory infiltrates. Thus ABRA would be a definable subset of PCNSV characterized by older age, high frequency of cognitive dysfunction and seizures/spells, increased spinal fluid protein levels, high frequency of enhancing leptomeningeal lesions, and favorable response to glucocorticoids alone or in combination with cyclophosphamide [30,34]. In our patient focal seizures have preceded the lobar hematoma, as already described in patients with CAA [35]. Also in this age group CAA would be the most probable diagnosis, rather than PCNSV. Notwithstanding, intracranial hemorrhage was reported in 12.2% of patients with PCNSV [36], intracerebral hemorrhage being more frequent than SAH. In our patient the diagnosis of CAA-RI was made. It is possible that CAA-RI and ABRA are part of the same pathologic spectrum and imaging abnormalities suggestive of vasogenic edema/mass effect have been reported in a significant number of patients with ABRA or CAA-RI [37]. Our patient had a clear response to steroids, clinical worsening as steroids were tapered, and stabilization with cyclophosphamide, which suggested that inflammation was responsible for the clinical symptoms.

Documenting cerebral vessel inflammation

Case 5. Does this middle-aged woman with recurrent strokes, dementia, elevated ESR, and several cerebral artery stenoses have cerebral vasculitis? A case of angiography positive PCNSV

Case description

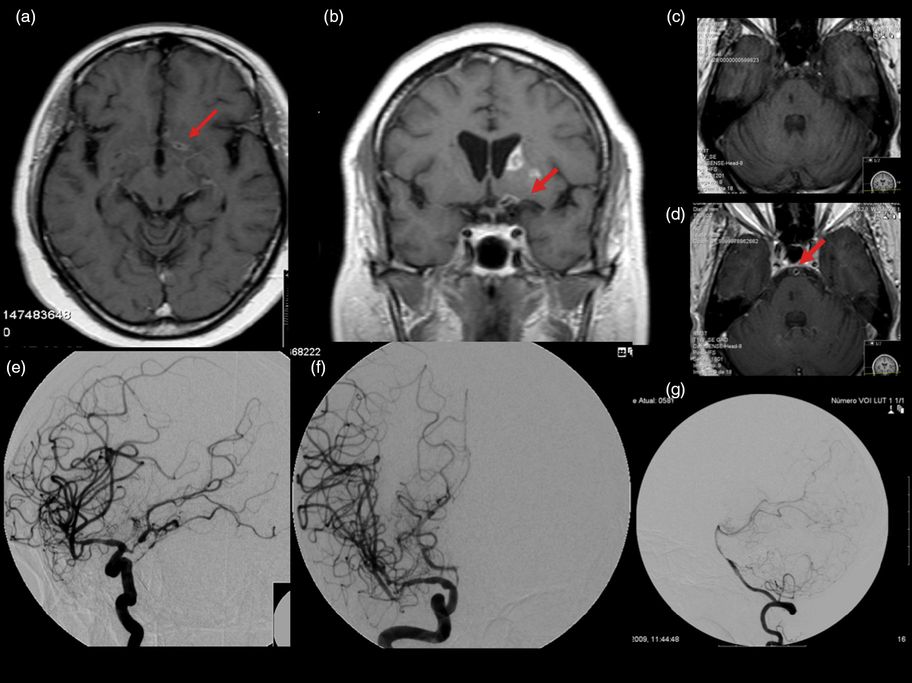

A 58-year-old hypertensive black woman had (3 months before admission) a posterior circulation ischemic stroke, with mild left hemiparesis and gait ataxia. She was readmitted due to sudden onset of right hemichorea. The patient had worked as an accountant and was independent until 6 months before admission. Since then, her family had noticed progressive behavioral changes with lack of initiative, memory loss, and lack of insight that clearly interfered with her daily life activities. She also complained of constant headaches. General examination was unremarkable. On neurological examination she was disoriented in time and space, had verbal memory impairment, low verbal output, and a grade 4 right hemiparesis and right hemibody choreic movements. Brain MRI disclosed a recent ischemic lesion in the left caudate nucleus and anterior limb of the internal capsule and several non-recent ischemic lesions, extensive leukoaraiosis and gadolinium enhancement of both ACAs, left MCA (Figure 11.5a and b), and basilar artery (Figure 11.5c and d), without leptomeningeal enhancement. Conventional cerebral angiography showed multiple stenoses of the proximal segments of intracranial arteries (particularly segmental stenosis with poststenotic dilation of the distal M1 segment and M2 right MCA), right posterior communicating artery aneurysm, left intracranial internal carotid artery stenosis with marked poststenotic dilatation, irregularities of the A1 segment of the left ACA, and irregularities of the basilar artery (especially middle third) (Figure 11.5e, f, and g).

Angiography positive primary central nervous system vasculitis. (a and b) Brain MRI (T1 after gadolinium injection) disclosed a recent ischemic lesion in the left caudate nucleus and anterior capsule and gadolinium enhancement of left middle cerebral artery and (c) basilar artery (c before and d after gadolinium injection) (arrows), without leptomeningeal enhancement. Conventional cerebral angiography revealed (e) left intracranial internal carotid stenosis with marked poststenotic dilatation, (f) irregularities of the A1 segment of left anterior cerebral artery, and (g) irregularity of the basilar artery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree