11 The dissociative (conversion) and hypochondriasis and other somatoform disorders

Introduction

The old hysterical neurosis is now described in ICD-10 under the term Dissociative (Conversion) Disorders (see Table 11.1)and includes the concepts of:

Table 11.1 Dissociative (conversion) disorders as described in ICD-10

| Common themes |

| Partial or complete loss of normal integration between memories of the past, awareness of identity and immediate sensations and control of bodily movements |

| The term conversion is applied to some of these disorders and implies that unresolved problems and conflicts are transformed into symptoms, e.g. paralysis and anaesthesias |

| Denial of problems and difficulties that are obvious to others |

| No evidence of physical disorder that might explain symptoms |

| Evidence of psychological causation in the form of association in time with stressful events and problems or disturbed relationships |

| Specific disorders |

| Dissociative amnesia – loss of memory (partial or complete) for recent events of a traumatic or stressful nature |

| Dissociative fugue |

| Dissociative stupor – profound diminution or absence of voluntary movement and normal responsiveness to external stimuli |

| Trance and possession states |

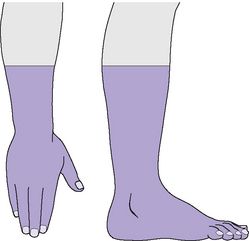

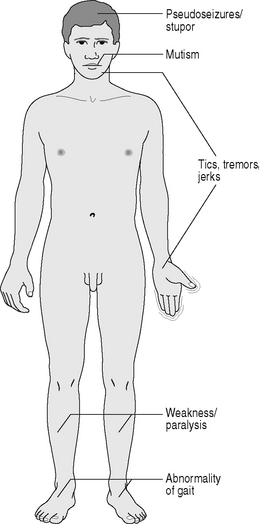

| Dissociative disorders of movement and sensation – e.g. loss of ability to move all or part of limb(s); sometimes accompanied by calm acceptance (la belle indifférence) |

| Dissociative convulsions (pseudoseizures) |

| Other dissociative and conversion disorders – e.g.Ganser’ syndrome, multiple personality |

Table 11.2 shows the varied meanings of hysteria used in the present and the past.

Table 11.2 Varied meanings of hysteria

| Hysterical neurosis |

| This is now described in ICD:10 under the term Dissociative (Conversion) Disorders. |

| Hysterical symptoms |

| These may occur in other mental illnesses, such as depression and anxiety, and may also complicate organic disease. |

| Epidemic (communicable) hysteria or mass hysteria |

| In this condition there may be a widespread outbreak of particular hysterical or other symptoms, such as fainting, hyperventilation, emotional distress and abdominal pain. This often occurs among young females and/or in institutions such as schools. There is often a background of tension or apprehension, and the initial symptoms may appear in an influential or powerful figure and then spread, by suggestion, to younger or less influential individuals, while excluding outsiders or those more intellectually able. Food or chemical poisoning or infection may initially be suspected, which only increases the emotional tension. In the Middle Ages dancing mania swept through Europe, although alternative explanations have been given for this in terms of an infective neurological disorder causing limb restlessness. |

| Hysterical or histrionic personality disorder |

| Such individuals have overemotional and overdramatic personality traits. They may crave attention and be manipulative. Under stress they have an increased vulnerability to developing dissociative (conversion) disorders and are also prone to parasuicidal acts. |

| Hysterical (histrionic) behaviour |

| This term is frequently used, not only by the general public, to refer to behaviour where there is ‘acting out’ of problems, and also loss of or poor control of impulses. Such behaviour occurs particularly in histrionic or psychopathic personalities. It is useful to distinguish the conscious motivation for such behaviour from the unconscious motivation underlying hysterical symptoms in dissociative (conversion) disorders. |

| Hysterical patients |

| This is a term of abuse often applied by doctors to patients, usually female, when the doctor is irritated because of a belief that the patient may be exaggerating her symptoms or the doctor has a feeling of being manipulated. Similar male patients tend to be labelled psychopaths. The use of the term hysterical in this way usually reflects an unsatisfactory doctor–patientrelationship. |

| St Louis hysteria Briquet’ syndrome) |

| Also known as somatization disorder, this refers to individuals with recurrent and multiple unexplained physical symptoms commencing before the age of 30 years and of chronic duration. |

| Hysterical psychosis or hysterical pseudopsychosis |

| This is a group of pseudopsychotic disorders, with pseudodelusions and pseudohallucinations, which occur suddenly after severe emotional stress and usually end abruptly within a few days. Such pseudohallucinations are experienced as arising within the mind, rather than being perceived by actual sense organs. They are a form of vivid imagery, located in subjective rather than external objective space, but not subject to conscious control. Included in such disorders are a number of culture-bound disorders, such as ‘running amok’ in south-east Asia and, from history, the Vikings ‘going berserk’. It has been suggested that Joan of Arc suffered from a hysterical psychosis. |

| Anxiety hysteria |

| This is a psychoanalytic term for phobic anxiety. |

In ICD-10, the category of dissociative (conversion) disorders includes conversion disorder (previously hysterical neurosis, conversion type). In DSM-IV-TR, the category of dissociative disorders does not include conversion disorder, which is subsumed under the category of somatoform disorders. Table 11.3compares the nomenclature for these disorders in ICD-10 and DSM-IV-TR.

Table 11.3 Comparison of ICD-10 and DSM-IV-TR somatoform and dissociative disorders

| ICD-10 | DSM-IV-TR |

|---|---|

| F44 Dissociative (conversion) disorders | 300 Dissociative disorders |

| F45 Somatoform disorders | 300 Somatoform disorders |

| F45.0 Somatization disorder | 300.81 Somatization disorder |

| F45.2 Hypochondriacal disorder | 300.7 Hypochondriasis |

| F45.4 Persistent somatoform pain disorder | 307.80 Pain disorder |

Varied meanings of the term hysteria

Dissociative disorders

These are characterized by a psychogenic (psychologically caused)alteration in an individual’ state of consciousness or personal identity. Table 11.1 summarizes the description of dissociative disorders given in ICD-10.

Conversion disorders

Clinical features

Aetiology

Predisposing factors

There is little evidence in favour of a genetic predisposition to conversion disorders.

Learning theory explains conversion disorders in terms of classical conditioning.

Precipitating and perpetuating factors

The condition is perpetuated by secondary gain and the advantages of the sick role (see above).

The possibility of financial gain, such as in compensation neurosis, may also perpetuate the disorder.Table 11.4 summarizes the aetiology of conversion disorders.

Table 11.4 Aetiology of conversion disorders

| Predisposing factors | Childhood experience of illness |

| Precipitating factors | Physical illness, e.g. epilepsy, Guillain–Barré syndrome |

| Negative life events | |

| Relationship conflict | |

| Modelling of others’ illness | |

| Perpetuating factors | Behavioural responses, e.g. avoidance, disuse, reassurance seeking |

| Cognitive responses, e.g. fear of worsening, fear of serious disease |

Prognosis

Dissociative and conversion disorders

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree