2 The life net

Introduction

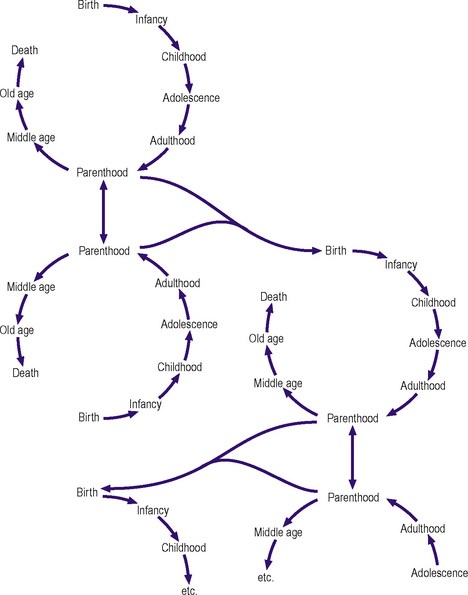

In another sense the perpetuation of the species is a ‘cycle’ of birth and death. In the following this notion is extended to consider a series of interlocking and interrelated life scripts or lines, which trace human development (Figure 2.1). These are punctuated by life events, some significant, some less significant depending on context, but at many of which doctors are present or involved. At each consultation the doctor sees only a snapshot of a person, family or community and their predicament. However, each predicament has its history and influences, which must be taken into account in determining, first, a formulation of the most prominent problem at that time, second, the most appropriate intervention, and, third, the likelihood of change in a wanted direction.

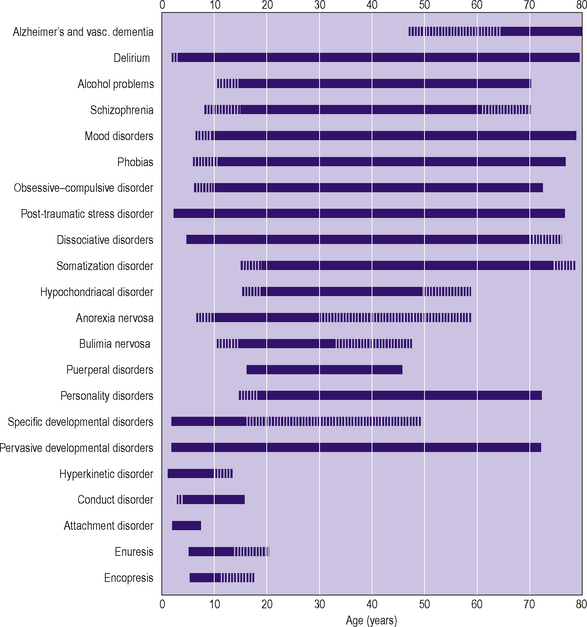

All psychiatric disorder occurs in a developmental context. There are characteristic life events, interactions with the lives of others and psychiatric disorders at each developmental stage. Some behaviours may be considered within the normal range at one age but as evidence of disorder at another (e.g. belief in Santa Claus would, in some Western cultures, be normal at age 4, but thought very strange at age 24). This example also illustrates the importance of context: if the 24-year-old was professing the belief in an infant school classroom, it would be less worrying than if it was reported in all seriousness in a consulting room (Figure 2.2).

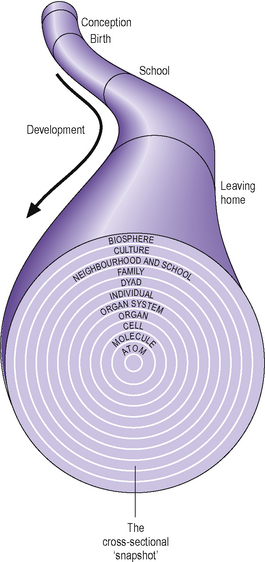

Since Descartes, Westerners have got used to considering the mind and body as separate entities. Macroscopically and microscopically this is spurious. All disorders – indeed all of life – have both psychological and physical components: even a fracture is determined by the psychological ‘set’ that led to the activity in which the fracture occurred, and the care that was taken over the activity. Similarly, the speed and circumstances of recovery and any subsequent disability may be determined as much by psychological as physical factors. Conversely, one cannot have a ‘thought’ without a corresponding parallel electrical and biochemical configuration in the brain. A multilevel developmental approach is illustrated schematically in Figure 2.3.

Where to start?

Postnatal or puerperal depression occurs in 10–20% of women, depending on the criteria used. In some this will develop into a psychosis (see Chapter 12). The rapidity or otherwise with which this resolves will have an effect on the whole family, but in particular on the developing infant. It has been shown that there is poor coordination in the interactions between a depressed mother and her child, as though the ‘give and take’ is ‘out of step’. The infant becomes distressed and avoids interaction, which, in turn, affects the mother’s approaches, and their frequency and type. It has even been observed that maternal depression is associated with subsequent delays in the cognitive development of the infant. Also of later concern may be problems of attachment, although these may be mitigated by the availability of other carers.

‘Attachment’ is the quality of interaction between a child and its principal carer. It can be disrupted or altered by life events or disorders affecting the child, its carer or both. Clinical evidence suggests that quality of initial attachment is a template for future relationships. Also, the type of attachment experienced in early life will influence the speed and manner with which the various levels of independence are achieved. Both of these can influence the risk of developing a psychiatric disorder at a later stage in the life cycle (see Chapter 16).

In childhood the sorts of problems presenting to psychiatry are largely dictated by the stage of development and the expectations of the child’s carers. For example, most parents expect to be woken at night by a newborn infant, but they also expect the infant gradually to develop a sleep–wake cycle that resembles that of the rest of the family. If this does not occur and there are problems settling or night-time waking, then a sleep disorder may be presented (see Chapter 16). Similarly, when there are delays, abnormalities or excesses in behaviours at different stages of childhood, which cause suffering and/or handicap, then other child psychiatric disorders may be present.