The misuse of alcohol and drugs

Classification of substance use disorders

Introduction

The presentation of alcohol and drug misuse is not limited to any particular psychiatric or indeed medical specialty. Alcohol and drug use may play an important part in all aspects of psychiatric practice, and is relevant, for example, to the assessment of a patient with acute confusion on a medical ward, a suicidal patient in the Accident and Emergency department, an elderly patient whose self-care has deteriorated, a troubled adolescent, or a disturbed child who may be inhaling volatile substances.

The phrases substance use disorder (DSM-IV) or disorders due to psychoactive drug use (ICD-10) are used to refer to conditions arising from the misuse of alcohol, psychoactive drugs, or other chemicals such as volatile substances. In this chapter, problems related to alcohol will be discussed first under the general heading of alcohol use disorders. Problems related to drugs and other chemicals will then be discussed under the general heading of other substance use disorders.

Classification of substance use disorders

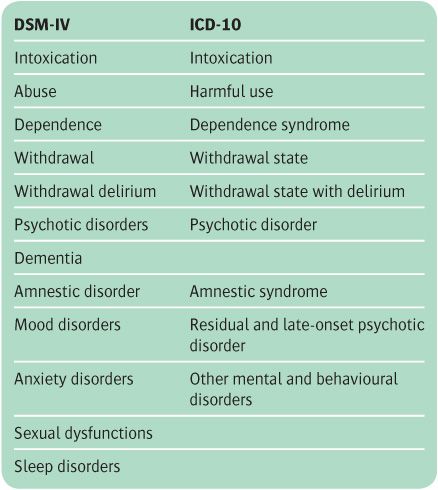

The two classification systems, DSM-IV and ICD-10, use similar categories for substance use disorders but group them in different ways. Both schemes recognize the following disorders: intoxication, abuse (or harmful use), dependence, withdrawal states, psychotic disorders, and amnestic syndromes. These and some additional categories are shown in Table 17.1.

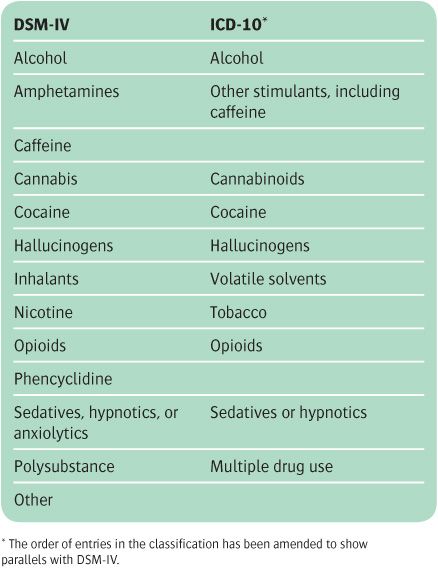

In both diagnostic systems the first step in classification is to specify the substance or class of substance that is involved (see Table 17.2); this provides the primary diagnostic category. Although many drug users take more than one kind of drug, the diagnosis of the disorder is made on the basis of the most important substance used. Where this judgement is difficult or where use is chaotic and indiscriminate, the categories polysubstance-related disorder (DSM-IV) or disorder due to multiple drug use (ICD-10) may be employed. Then the relevant disorder listed in Table 17.1 is added to the substance misused. In this system any kind of disorder can, in principle, be attached to any drug, although in practice certain disorders do not develop with individual drugs. ICD-10 also has a specific category, residual and late-onset psychotic disorder, which describes physiological or psychological changes that occur when a drug is taken but then persist beyond the period during which a direct effect of the substance would reasonably be expected to be operating. Such categories might include hallucinogen-induced flashbacks and alcohol-related dementia.

Definitions in DSM-IV and ICD-10

Intoxication

Both DSM-IV and ICD-10 provide definitions of intoxication. In both systems, intoxication is considered to be a transient syndrome due to recent substance ingestion that produces clinically significant psychological and physical impairment. These changes disappear when the substance is eliminated from the body. The nature of the psychological changes varies with the individual as well as with the drug—for example, some people when intoxicated with alcohol become aggressive, while others become maudlin.

Table 17.1 Substance-related disorders

Table 17.2 Classes of substances

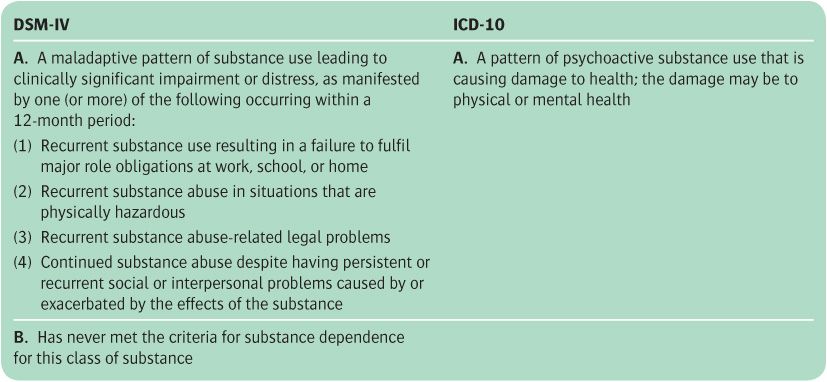

Table 17.3 Criteria for substance abuse (DSM-IV) and harmful use (ICD-10)

Abuse

The terms abuse in DSM-IV and harmful use in ICD-10 refer to maladaptive patterns of substance use that impair health in a broad sense (see Table 17.3). (The widely used term misuse carries a similar meaning.) The DSM and ICD criteria differ somewhat, with the emphasis being on negative social consequences of substance use in DSM-IV, and on adverse physical and psychological consequences in ICD-10. Some individuals show definite evidence of substance abuse but do not meet the criteria for substance dependence (see Table 17.4). However, if they do meet those criteria, the diagnosis of dependence should be made, not that of abuse or harmful use.

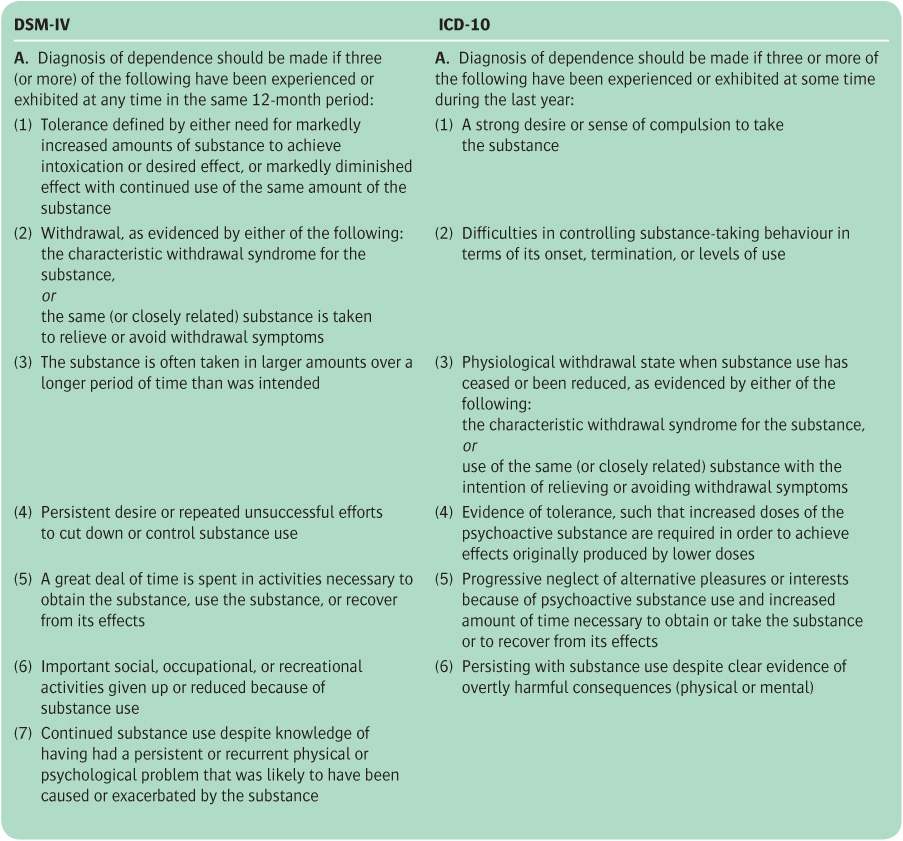

Dependence

The term dependence refers to certain physiological and psychological phenomena that are induced by the repeated taking of a substance. The criteria for diagnosing dependence are similar in DSM-IV and ICD-10, and include the following:

• a strong desire to take the substance

• progressive neglect of alternative sources of satisfaction

• the development of tolerance

• a physical withdrawal state (see Table 17.4).

Tolerance

This is a state in which, after repeated administration, a drug produces a decreased effect, or increasing doses are required to produce the same effect.

Table 17.4 Criteria for dependence in DSM-IV and ICD-10

Withdrawal state

This refers to a group of symptoms and signs that occur when a drug is reduced in amount or withdrawn, which last for a limited time. The nature of the withdrawal state is related to the class of substance used.

Alcohol-related disorders

Terminology

Alcoholism. In the past, the term alcoholism was generally used in medical writing. Although the word is still widely used in everyday language, it is unsatisfactory as a technical term because it has more than one meaning. It can be applied to habitual alcohol consumption that is deemed excessive in amount according to some arbitrary criterion, and it may also refer to damage, whether mental, physical, or social, resulting from such excessive consumption. In a more specialized sense, alcoholism may imply a specific disease entity that is supposed to require medical treatment. However, to speak of an alcoholic often has a pejorative meaning, suggesting behaviour that is morally bad. For most purposes it is better to use four terms that relate to the classifications outlined above.

1. Excessive consumption of alcohol. This refers to a daily or weekly intake of alcohol that exceeds a specified amount (see below). Excessive consumption of alcohol is also known as hazardous drinking. Harmful drinking is a term used to describe levels of hazardous drinking at which damage to health is very likely.

2. Alcohol misuse. This refers to drinking that causes mental, physical, or social harm to an individual. However, it does not include those with formal alcohol dependence.

3. Alcohol dependence. This term can be used when the criteria for a dependence syndrome listed in Table 17.4 are met.

4. Problem drinking. This term is applied to those in whom drinking has caused an alcohol-related disorder or disability. Its meaning is essentially similar to alcohol misuse, but it can also include drinkers who are dependent on alcohol.

The term alcoholism, if it is used at all, should be regarded as a shorthand way of referring to some combination of these four conditions. However, since these specific terms have been introduced fairly recently, the term alcoholism has been used in this chapter when referring to the older literature.

At this point it is appropriate to examine the moral and medical models of alcohol misuse.

The moral and medical models

According to the moral model, if someone drinks too much, they do so of their own free will, and if their drinking causes harm to them or their family, their actions are morally bad. The corollary of this attitude is that public drunkenness should be punished. In many countries this is the official practice; public drunks are fined, and if they cannot pay the fine they go to prison. Many people now believe that this approach is too harsh and unsympathetic. Whatever the humanitarian arguments, there is little practical justification for punishment, since there is little evidence that it influences the behaviour of dependent drinkers. However, it is possible that social disapproval could play a role in dissuading non-dependent drinkers from excessive consumption.

According to the medical model, a person who misuses alcohol is ill rather than wicked. Although it had been proposed earlier, this idea was not strongly advocated until 1960, when Jellinek published an influential book, The Disease Concept of Alcoholism. The disease concept embodies three basic ideas.

1. Some people have a specific vulnerability to alcohol misuse.

2. Excessive drinking progresses through well-defined stages, at one of which the person can no longer control their drinking.

3. Excessive drinking may lead to physical and mental disease of several kinds.

One of the main consequences of the disease model is that attitudes towards excessive drinking become more humane. Instead of blame and punishment, medical treatment is provided. The disease model also has certain disadvantages. By implying that only certain people are at risk, it diverts attention from some important facts. First, anyone who drinks a great deal for a long time may become dependent on alcohol. Secondly, the best way to curtail the misuse of alcohol may be to limit consumption in the whole population, and not just among a predisposed minority. Thirdly, it may suggest that excessive drinking, at least initially, is not a product of a personal choice.

Perhaps a useful way to resolve these two approaches is to apply the moral model to excessive drinking in the population in the hope of decreasing the number of people who put themselves at risk of alcohol-related disability. However, once dependence has occurred, with its attendant loss of control over drinking, a medical approach may be more appropriate.

Excessive alcohol consumption

In many societies the use of alcohol is sanctioned and even encouraged by sophisticated marketing techniques. Therefore the level of drinking at which an individual is considered to demonstrate excessive alcohol consumption is a somewhat arbitrary concept, which is usually defined in terms of the level of use associated with significant risk of alcohol-related health and social problems. It is usually expressed in units of alcohol consumed per week. For example, in the UK, current government advice is that men should not drink more than 3–4 units of alcohol a day, while for women the limit is 2–3 units a day. Above these limits the risk of health and social problems increases generally in proportion to the amount of alcohol consumed. Men who regularly drink more than 50 units a week and women who regularly drink more than 35 units a week are seen as harmful drinkers (Department of Health, 2007a).

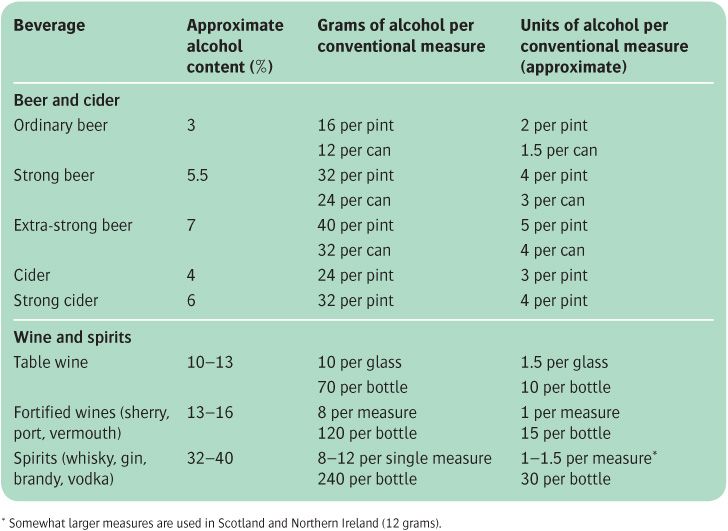

If the concept of excessive alcohol consumption is to be understood and accepted, it is necessary to explain the units in which it is assessed. In everyday life, this is done by referring to conventional measures such as pints of beer or glasses of wine. These measures have the advantage of being widely understood, but they are imprecise because both beers and wines vary in strength (see Table 17.5). Alternatively, consumption can be measured as the amount of alcohol (expressed in grams). This measure is precise and useful for scientific work, but is difficult for many people to relate to everyday measures.

For this reason, the concept of a unit of alcohol has been introduced for use in health education. A unit can be related to everyday measures because it corresponds to half a pint of beer, one glass of table wine, one conventional glass of sherry or port, and one single bar measure of spirits. It can also be related to average amounts of alcohol (see Table 17.5). Thus on this measure a can of beer (450 ml) contains nearly 1.5 units, a bottle of table wine contains about 10 units, a bottle of spirits contains about 30 units, and 1 unit is about 8 g of alcohol. The increase in strength of wine and beer over the last two decades has made many of these calculations difficult. Wine sold in the UK now contains an average of 12–13% alcohol, and sometimes more. To compound matters, the size of wine glass used in most restaurants has increased from 125 ml to 175 ml, so that an average serving in a restaurant or public house is equivalent to a minimum of 2 units.

Epidemiological aspects of excessive drinking and alcohol misuse

Epidemiological methods can be applied to the following questions concerning excessive drinking and alcohol misuse.

1. What is the annual per capita consumption of alcohol for a nation as a whole, and how does this vary over the years and between nations?

2. What is the pattern of alcohol use of different groups of people within a defined population?

3. How many people in a defined population misuse alcohol?

4. How does alcohol misuse vary with such characteristics as gender, age, occupation, social class, and marital status?

Unfortunately, we lack reliable answers to these questions, partly because different investigators have used different methods of defining and identifying alcohol misuse and ‘alcoholism’, and partly because excessive drinkers tend to be evasive about the amount that they drink and the symptoms that they experience.

Consumption of alcohol in different countries

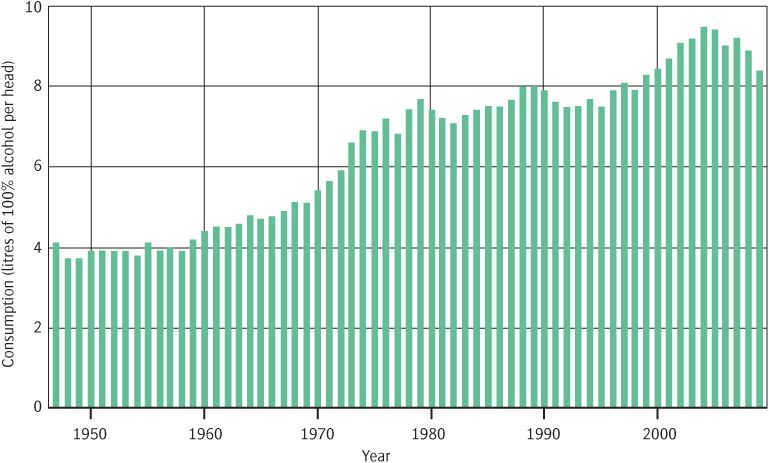

In the UK, the annual consumption of alcohol per adult (calculated as absolute ethanol consumption) doubled between 1960 and 2000, rising from about 4 litres to over 8 litres. Consumption in Western Europe has generally been higher than this, particularly in France. High levels of consumption are also seen in the former Soviet Union, while in the Eastern Mediterrean and in Muslim countries consumption is much less.

Recent changes in the UK can be usefully considered in a historical perspective. For example, in Great Britain between 1860 and 1900 the annual consumption of alcohol was about 10 litres of absolute alcohol per head of population over 15 years of age. It then fell until the early 1930s, reaching about 4 litres per person over 15 years of age per annum. Consumption then increased slowly until the 1950s, when it began to rise more rapidly. Over the last few years there has been a small drop in annual consumption, but the average annual amount is still about twice what it was in the 1950s (see Figure 17.1).

Table 17.5 Alcohol content of some beverages

Figure 17.1 Average annual consumption of alcohol in the UK between 1947 and 2009. Source: British Beer and Pub Association (2010). BBPA Statistical Handbook, 2010. British Beer and Pub Association, London.

These changes have been accompanied by changes in the kinds of alcoholic beverages consumed. In Britain in 1900, beer and spirits accounted for most of the alcohol that was drunk. By 1980 the consumption of wine had risen about fourfold, and accounted for almost as much of the consumption of alcohol as did spirits, although most alcohol was still consumed as beer (see Figure 17.1).

Drinking habits in different groups. Surveys of drinking behaviour generally depend on self-reports, a method which is open to obvious errors. Enquiries of this kind have been conducted in several countries, including the UK and the USA. Such studies show that the highest reported consumption of alcohol is generally among young men who are unmarried, separated, or divorced. However, over the last 15 years drinking by women has increased. Based on population estimates in 2008, men in England drank on average 16.8 units of alcohol a week, whereas women drank on average 8.6 units per week. Around 18% of school pupils aged 11 to 15 years reported drinking alcohol in the week prior to interview; this figure is lower than that for 2001, when 26% of pupils reported drinking in the preceding week (Office for National Statistics, 2010).

The prevalence of alcohol misuse

This can be estimated in three ways—from hospital admission rates, from deaths from alcoholic cirrhosis, and by surveys of the general population.

Hospital admission rates. These give an inadequate measure of prevalence, because a large proportion of excessive drinkers are not admitted to hospital.

• In England during the period 2007–2008 there were about 62 000 NHS hospital admissions with a primary diagnosis of mental and behavioural disorders due to alcohol (Office for National Statistics, 2009).

• Alcohol is estimated to be a causal factor in about one-third of attendances at Accident and Emergency services (Academy of Medical Sciences, 2004).

Deaths from alcoholic cirrhosis. About 10–20% of people who drink alcohol excessively develop cirrhosis of the liver, and there are correlations in a population between rates of liver cirrhosis and mean alcohol consumption. Therefore deaths from cirrhosis can be used as a means of estimating rates of alcohol misuse. Rates of mortality from liver cirrhosis are showing a decline in a number of developed countries. For example, in southern Europe there has been a sustained decrease in deaths from cirrhosis, probably as a result of fiscal law enforcement and health promotion policies. On the other hand, alcoholic liver cirrhosis appear to be increasing in England, with deaths attributable to this cause rising from 3236 in 2001 to 4400 in 2008, an increase of 36% (Office for National Statistics, 2010).

General population surveys. One method of ascertaining the rate of alcohol misuse in a population is by seeking information from general practitioners, social workers, probation officers, health visitors, and other agencies who are likely to come into contact with heavy drinkers. Another approach is the community survey, in which samples of people are asked about the amount they drink and whether they experience symptoms. For example, the National Survey Comorbidity Replication in the USA found a 1-year prevalence rate for DSM-IV alcohol abuse of 3.1%, while the prevalence of alcohol dependence was 1.3% (Kessler et al., 2005b). The Psychiatric Morbidity Survey in England, reporting 6-month prevalences, classified 24% of adults living in households as hazardous drinkers, and 6% as alcohol dependent (although 5% of these individuals were classified as having ‘mild’ dependence) (McManus et al., 2007). Over time there are significant individual fluctuations in alcohol consumption, with a substantial proportion of people moving from hazardous drinking towards safer drinking, while others move into the hazardous drinking category.

Surveys based on households are likely to miss certain groups at high risk of alcohol misuse and dependence. The British Psychiatric Morbidity Survey sampled separately from homeless populations and from those in institutions such as prisons. Among people living in night shelters or sleeping rough, 40% were found to drink more than 50 units of alcohol a week, and about 35% of those sleeping rough were estimated to have severe alcohol dependence (Gill et al., 1996).

Alcohol misuse and population characteristics

Gender. Rates of alcohol misuse and dependence are consistently higher in men than in women, but the ratio of affected men to women varies markedly across cultures. In Western countries, about three times as many men as women suffer from alcohol misuse and dependence, but in Asian and Hispanic cultures a higher ratio of men to women are affected. In the Psychiatric Morbidity Survey in England the rate of hazardous drinking among white men (36%) was more than twice as high as that among white women (16%), while the rate among South Asian men (12%) was four times higher than that among South Asian women (3%) (McManus et al., 2007). However, perhaps because of changing social attitudes, the gap between men and women with regard to excessive drinking seems to be narrowing in many Western countries. This is of concern because studies indicate that women are more susceptible than men to many of the damaging effects of alcohol (see below).

Age. We have seen that the heaviest drinkers are men in their late teens or early twenties. In most cultures the prevalence of alcohol misuse and dependence is lower in those aged over 45 years.

Ethnicity and culture. The followers of certain religions which proscribe alcohol (e.g. Islam, Hinduism, and the Baptist Church) are less likely than the general population to misuse alcohol. It is also worth noting that the non-white population in the UK and the USA are less likely to drink excessively than the white population, and therefore have a lower rate of alcohol-related disorders. In some instances, the low consumption of alcohol in a particular ethnic group may be due to a biologically determined lack of tolerance to alcohol. For example, Asians with a particular variant of the isoenzyme of aldehyde dehydrogenase experience flushing, nausea, and tachycardia due to accumulation of acetaldehyde when they drink alcohol. Such individuals are likely to be at reduced risk of excess drinking and the consequent development of alcohol-related disorders. Thus, although the aldehyde dehydrogenase variant that causes the flushing reaction was present in 35% of the general Japanese population, it was found in only 7% of Japanese patients with alcoholic liver disease (Shibuya and Yoshida, 1988).

Occupation. The risk of alcohol misuse is much increased among several occupational groups. These include chefs, kitchen porters, barmen, and brewery workers, who have easy access to alcohol, executives and salesmen who entertain on expense accounts, actors and entertainers, seamen, and journalists. Doctors have been said to have an increased risk of harmful drinking, but whether this is in fact the case has been questioned. However, doctors do have higher rates of prescription drug misuse, and treatment programmes for both this problem and alcohol-related disorders may be difficult to institute (Marshall, 2008).

Syndromes of alcohol dependence and alcohol withdrawal

Patients are described as alcohol dependent when they meet the criteria for substance dependence described in Table 17.4. The presence of withdrawal phenomena is not necessary for the diagnosis of dependence, and a substantial minority of individuals who meet the dependence criteria do not experience any withdrawal phenomena when their intake of alcohol decreases or stops. However, about 5% of dependent individuals experience severe withdrawal symptomatology, including delirium tremens and grand mal seizures.

Course of alcohol misuse and dependence

Schuckit et al. (1993) reviewed the course of over 600 men with alcohol dependence who received inpatient treatment at a single facility in the USA between 1985 and 1991. These individuals showed a general pattern of escalation of heavy drinking in their late twenties followed by evidence of serious difficulties in work and social life by their early thirties. In their middle to late thirties, following the perception that they could not control their drinking, they experienced increasing social and work-related problems, together with a significant deterioration in physical health.

Vaillant (2003) described a 60-year follow-up of 194 men who had exhibited misuse of alcohol at some point in their adult life. By the age of 70 years over 50% of the cohort had died and about 20% were abstinent. Around 10% were drinking in a controlled way, while a further 10% continued to misuse alcohol. In a number of individuals alcohol misuse had apparently persisted for decades without remission, death, or progression to formal dependence. However, for alcohol-dependent men, periods of controlled drinking were invariably followed by a return to a pattern of alcohol dependence. Attendance at Alcoholics Anonymous was the best predictor of good outcome. This study suggests that the prognosis of alcohol misuse is very variable. However, once an individual has become alcohol dependent the prognosis is poor unless abstinence can be maintained.

The alcohol withdrawal syndrome

Withdrawal symptoms occur across a spectrum of severity, ranging from mild anxiety and sleep disturbance to the life-threatening state known as delirium tremens. The symptoms generally occur in people who have been drinking heavily for years and who maintain a high intake of alcohol for weeks at a time. The symptoms follow a drop in blood alcohol concentration. They characteristically appear on waking, after the fall in concentration has occurred during sleep. Dependent drinkers often take a drink on waking to stave off withdrawal symptoms. In most cultures, early-morning drinking is diagnostic of dependency. With the increasing need to stave off withdrawal symptoms during the day, the drinker typically becomes secretive about the amount consumed, hides bottles, or carries them in a pocket. Rough cider and cheap strong beers may be drunk regularly in order to obtain the most alcohol for the minimum cost.

The earliest and commonest feature of alcohol withdrawal is acute tremulousness affecting the hands, legs, and trunk (‘the shakes’). The sufferer may be unable to sit still, hold a cup steady, or fasten up buttons. They are also agitated and easily startled, and often dread facing people or crossing the road. Nausea, retching, and sweating are frequent. Insomnia is also common. If alcohol is taken, these symptoms may be relieved quickly; otherwise they may last for several days (see Table 17.6).

Table 17.6 Symptoms and signs of acute alcohol withdrawal

Anxiety, agitation, and insomnia |

Tachycardia and sweating |

Tremor of limbs, tongue and eyelids |

Nausea and vomiting |

Seizures |

Confusion and hallucinations |

From Ritson (2005).

As withdrawal progresses, misperceptions and hallucinations may occur, usually only briefly. Objects appear distorted in shape, or shadows seem to move; disorganized voices, shouting, or snatches of music may be heard. Later there may be epileptic seizures, and finally after about 48 hours delirium tremens may develop.

Other alcohol-related disorders

The different types of damage—physical, psychological, and social—that can result from alcohol misuse are described in this section. A person who suffers from these disabilities may or may not be suffering from alcohol dependence.

Physical damage

Excessive consumption of alcohol may lead to physical damage in several ways. First, it can have a direct toxic effect on certain tissues, notably the brain and liver. Secondly, it is often accompanied by poor diet, which may lead to deficiency of protein and B vitamins. Thirdly, it increases the risk of accidents, particularly head injury. Fourthly, it is accompanied by general neglect which can lead to increased susceptibility to infection.

Gastrointestinal disorders

Gastrointestinal disorders are common, notably liver damage, gastritis, peptic ulcer, oesophageal varices, and acute and chronic pancreatitis. Damage to the liver, including fatty infiltration, hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatoma, is particularly important. For a person who is dependent on alcohol, the risk of dying from liver cirrhosis is almost ten times greater than the average. However, only about 10–20% of alcohol-dependent people develop cirrhosis.

Nervous system

Alcohol also damages the nervous system. Neuropsychiatric complications are described later; other neurological conditions include peripheral neuropathy, epilepsy, and cerebellar degeneration. The last of these is characterized by unsteadiness of stance and gait, with less effect on arm movements or speech. Rare complications are optic atrophy, central pontine myelinolysis, and Marchiafava–Bignami syndrome. The latter condition results from widespread demyelination of the corpus callosum, optic tracts, and cerebellar peduncles. Its main features are dysarthria, ataxia, epilepsy, and marked impairment of consciousness; in the more prolonged forms, dementia and limb paralysis occur. Head injury is also common in alcohol-dependent people.

Cardiovascular system

Alcohol misuse is associated with hypertension and increased risk of stroke. Paradoxically, men who drink moderate amounts of alcohol (up to about 10 units a week) appear to be less likely than non-drinkers to die from coronary artery disease (Beulens et al., 2010). Alcohol misuse has also been linked to the development of certain cancers, notably of the mouth, pharynx, oesophagus, liver, and breast.

Other physical complications of excessive consumption of alcohol are too numerous to detail here. Examples include anaemia, myopathy, episodic hypoglycaemia, haemochromatosis, cardiomyopathy, vitamin deficiencies, and tuberculosis. They are described in textbooks of medicine, such as the Oxford Textbook of Medicine (Warrell et al., 2010).

Alcohol misuse in women

Studies suggest that women progress more rapidly than men to problem drinking, and tend to suffer the medical consequences of alcohol use after a shorter period of exposure to a smaller amount of alcohol. As well as the expected medical complications noted above, female drinkers also show elevated rates of breast cancer and reproductive pathology, including amenorrhoea, anovulation, and possibly early menopause.

Damage to the fetus

There is evidence that a fetal alcohol syndrome occurs in children born to mothers who drink excessively. In France, Lemoine et al. (1968) described a syndrome of facial abnormality, small stature, low birth weight, low intelligence, and overactivity. Fetal alcohol syndrome is associated with clearly excessive alcohol use during pregnancy. However, subsequent research has suggested that even moderate or low levels of alcohol consumption at this time can have adverse effects on childhood development, and the ‘safe limit’ for alcohol consumption during pregnancy (if such a level exists) is not known. Current advice is that women should avoid alcohol during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy, and thereafter consume no more than one to two drinks a week (Khalil and O’Brien, 2010).

Mortality

People with a low level of alcohol consumption (about 1 unit daily) have decreased mortality rates compared with non-drinkers (Doll et al., 2005). This is mainly attributable to lowered cardiovascular mortality (see above). Not surprisingly, however, the mortality rate is increased in those who misuse alcohol. Follow-up investigations have studied mainly middle-aged men drinking excessively, in whom overall mortality is at least twice the expected rate, and mortality in women who drink excessively appears to be substantially higher than this (Harris and Barraclough, 1998). In England it has been estimated that about 15 000 deaths a year are directly attributable to the medical consequences of alcohol misuse (Office for National Statistics, 2010). Of course, alcohol must contribute indirectly to many more deaths from causes such as accidents. At a global level, the World Health Organization has estimated that alcohol causes 1.8 million deaths annually (about 3.2% of all deaths).

Psychiatric disorders

Alcohol-related psychiatric disorders fall into four groups:

• intoxication phenomena

• withdrawal phenomena

• toxic or nutritional disorders

• associated psychiatric disorders.

Intoxication phenomena

The severity of the symptoms of alcohol intoxication correlates approximately with the blood alcohol concentration. As noted above, there is much individual variation in the psychological effects of alcohol, but certain reactions, such as lability of mood and belligerence, are more likely to cause social difficulties. At high doses, alcohol intoxication can result in serious adverse effects, such as falls, respiratory depression, inhalation of vomit, and hypothermia.

The molecular mechanisms that underlie the acute effects of alcohol are unclear. An influential view has been that alcohol interacts with neuronal membranes to increase their fluidity—an action also ascribed to certain anaesthetic agents. This action gives rise to more specific changes in the release of a range of neurotransmitters, leading to the characteristic pharmacological actions of alcohol. For example, the pleasurable effects of alcohol use could be mediated by release of dopamine and opioids in the mesolimbic forebrain, while the anxiolytic effects could reflect facilitation of brain gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) activity (Lingford-Hughes et al., 2010).

The term idiosyncratic alcohol intoxication has been applied to marked maladaptive changes in behaviour, such as aggression, occurring within minutes of taking an amount of alcohol insufficient to induce intoxication in most people (with the behaviour being uncharacteristic of the affected individual). In the past, these sudden changes in behaviour were called pathological drunkenness, or manie à potu, and the descriptions emphasized the explosive nature of the outbursts of aggression. However, there is doubt as to whether behaviour of this kind really is induced by small amounts of alcohol. The term ‘idiosyncratic alcohol intoxication’ does not appear in DSM-IV or ICD-10.

Memory blackouts or short-term amnesia are frequently reported after heavy drinking. At first the events of the night before are forgotten, even though consciousness was maintained at the time. Such memory losses can occur after a single episode of heavy drinking in people who are not dependent on alcohol. If they recur regularly, they indicate habitual excessive consumption. With sustained excessive drinking, memory losses may become more severe, affecting parts of the daytime or even whole days.

Withdrawal phenomena

The general withdrawal syndrome has been described earlier under the heading of alcohol dependence. Here we are concerned with the more serious psychiatric syndrome of delirium tremens. Delirious states are described generally in Chapter 13, but delirium tremens is discussed here because of its prevalence and mortality, and its somewhat different treatment.

Delirium tremens occurs in people whose history of alcohol misuse extends over several years. Following alcohol withdrawal there is a dramatic and rapidly changing picture of disordered mental activity, with clouding of consciousness, disorientation in time and place, and impairment of recent memory. Perceptual disturbances include misinterpretations of sensory stimuli and vivid hallucinations, which are usually visual but sometimes occur in other modalities. There is severe agitation, with restlessness, shouting, and evident fear. Insomnia is prolonged. The hands are grossly tremulous and sometimes pick up imaginary objects; truncal ataxia may occur. Autonomic disturbances include sweating, fever, tachycardia, raised blood pressure, and dilatation of pupils. Dehydration and electrolyte disturbance are characteristic. Blood testing shows leucocytosis and impaired liver function.

The condition lasts for 3 or 4 days, with the symptoms characteristically being worse at night. It often ends with deep prolonged sleep from which the patient awakens with no symptoms and little or no memory of the period of delirium. Delirium tremens carries a significant risk of mortality and should be regarded as a medical emergency.

Toxic or nutritional conditions

These include Korsakov’s psychosis and Wernicke’s encephalopathy (see also Chapter 13), and alcoholic dementia, which is described next.

Alcoholic dementia. In the past there has been disagreement as to whether alcohol misuse can cause dementia. This doubt may have arisen because patients with general intellectual defects have been wrongly diagnosed as having Korsakov’s psychosis. However, it is now generally agreed that chronic alcohol misuse can cause cognitive impairment, particularly in tests of memory and executive function (Sullivan et al., 2010).

Attention has also been directed to the related question of whether chronic alcohol misuse can cause structural brain atrophy. Both computerized tomography (CT) scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have shown that excess alcohol consumption is associated with enlarged lateral ventricles. Furthermore, MRI scans have shown focal deficits, with loss of grey matter in both cortical and subcortical areas. Subcortical changes are more likely to be found in patients with Korsakov’s syndrome. Thinning of the corpus callosum has also been reported in patients with alcohol dependence. White matter changes are common in heavy drinkers, and studies using diffusion tensor imaging (see p. 112) indicate that there is demyelination.

Many of the changes noted above occur in patients without obvious neurological disturbance, although, as noted above, psychological testing usually reveals deficits in cognitive function. The changes in brain structure and cognitive impairment that are seen in excessive drinkers remit to some extent with cessation of alcohol use. However, some abnormalities can still be detected after long periods of abstinence.

For a review of brain imaging studies of the effects of alcohol, see Sullivan et al. (2010).

Associated psychiatric disorder

Personality deterioration. As the patient becomes increasingly concerned with the need to obtain alcohol, interpersonal skills and attention to their usual interests and responsibilities may deteriorate. These changes in social and interpersonal functioning should not be confused with personality disorder, which should be diagnosed only when the appropriate features have been clearly present prior to the development of alcohol dependence.

Mood and anxiety disorders. The relationship between alcohol consumption and mood is complex. On the one hand, some depressed and anxious patients drink excessively in an attempt to improve their mood. On the other hand, excess drinking may induce persistent depression or anxiety. People with a history of alcohol dependence have a fourfold increased risk of experiencing subsequent major depression, and the risk remains elevated even in those who are no longer drinking. The risk of experiencing an anxiety disorder is also significantly increased, but to a somewhat lesser extent (Anthenelli, 2010).

Suicidal behaviour. Suicide rates among people with alcohol use disorders are much higher than those among individuals who do not misuse alcohol. Conner and Duberstein (2004) identified a number of risk factors for suicidal behaviour among people with alcohol dependence, including impulsivity, negative affect, and hopelessness. Suicide among alcohol misusers is discussed further on p. 424. Here it is worth noting that suicide in young men is associated with a high rate of substance misuse, including alcohol misuse.

Pathological jealousy. Excessive drinkers may develop an overvalued idea or delusion that their partner is being unfaithful. This syndrome of pathological jealousy is described on p. 305.

Alcoholic hallucinosis. This is characterized by auditory hallucinations, usually involving voices uttering insults or threats, which occur in clear consciousness. The patient is usually distressed by these experiences, and appears anxious and restless. The hallucinations are not due to acute alcohol withdrawal, and can indeed persist after several months of abstinence. There has been considerable controversy about the aetiology of the condition. Some follow Kraepelin and Bonhoffer in regarding it as a rare organic complication of alcoholism; others follow Bleuler in supposing that it is related to schizophrenia. More recent reviewers have concluded that alcoholic hallucinosis is an alcohol-induced organic psychosis, which is distinct from schizophrenia and has a good prognosis if abstinence can be maintained (Mann and Kiefer, 2009).

In both DSM-IV and ICD-10, alcoholic hallucinosis is subsumed under the heading of substance-induced psychotic disorder.

Social damage (see Box 17.1)

Family problems

Excessive drinking is liable to cause profound social disruption, particularly in the family. Marital (or other relationship) and family tension is virtually inevitable. The divorce rate among heavy drinkers is high, and the partners of men who drink excessively are likely to become anxious, depressed, and socially isolated. The husbands of ‘battered wives’ frequently drink excessively, and some women who are admitted to hospital because of self-poisoning blame their partner’s drinking. The home atmosphere is often detrimental to any children present, because of quarrelling and violence, and a drunken parent provides a poor role model. Children of heavy drinkers are at risk of developing emotional or behavioural disorders, and of performing poorly at school.

Work difficulties and road accidents

At work, the heavy drinker often progresses through declining efficiency, lower-grade jobs, and repeated dismissals to lasting unemployment. There is also a strong association between road accidents and alcohol misuse. The strength of the association varies between countries. For example, in 2006, the proportion of fatal traffic accidents involving alcohol was about 17% in the UK, whereas the corresponding figures for France and Germany were about 27% and 11%, respectively. Whether these figures are attributable to real cross-national differences in the role of alcohol in traffic fatalities, or whether they are due to variations in methods of data collection and definition, is not certain (Assum and Sørensen, 2010).

Crime

Excessive drinking is also associated with crime, mainly petty offences such as larceny, but also with fraud, sexual offences, and crimes of violence, including murder. Studies of recidivist prisoners in England and Wales have shown that many of them had serious drinking problems before imprisonment. It is not easy to determine to what extent alcohol causes the criminal behaviour and to what extent it is part of the lifestyle of the criminal. In addition, there is a link between certain forms of alcohol misuse and antisocial personality disorder (see below).

The causes of excessive drinking and alcohol misuse

Despite much research, surprisingly little is known about the causes of excessive drinking and alcohol dependence. At one time it was believed that certain people were particularly predisposed, either through personality or due to an innate biochemical anomaly. Nowadays this simple notion of specific predisposition is no longer held. Instead, alcohol misuse is thought to result from a variety of interacting factors which can be divided into individual factors and those in society.

Individual factors

Genetic factors

Most genetic studies of alcoholism have investigated individuals with evidence of alcohol dependence. If less severe diagnostic criteria are involved—for example, fairly broadly defined alcohol misuse—the relative genetic contribution is somewhat less. However, it is well established that alcohol dependence aggregates in families, and twin studies show a higher concordance in MZ than DZ twins, with an estimated heritability of about 50% (Bienvenu et al., 2011).

Support for a genetic explanation also comes from investigations of adoptees. A number of studies have indicated a higher risk of alcohol misuse and dependence in the adopted-away sons of alcohol-dependent biological parents than in the adopted-away sons of non-alcohol-dependent biological parents. Such studies suggest a genetic mechanism, but they do not indicate its nature.

Adoption studies in Sweden led to the suggestion that there are two separate kinds of alcohol dependence, which have been called type 1 and type 2 (Cloninger et al., 1988). Type 2 alcoholism is strongly genetic, predominantly occurs in males, has an early age of onset, and is associated with criminality and sociopathic disorder in both adoptee and biological father. By contrast, type 1 alcoholism has a later age of onset, is only mildly genetic, and occurs in both men and women. Subsequent typologies of alcohol dependence have become more complex, but continue to include a group of alcohol-dependent people with early age of onset and sociopathic disorder. In others, however, an early age of onset of alcohol dependence is associated not with sociopathic traits but with high levels of anxiety-related symptoms (Leggio et al., 2009).

If a genetic component to aetiology were to be confirmed, it would still be necessary to discover the mechanism. The latter might be biochemical, involving the metabolism of alcohol or its central effects, or psychological, involving personality. In addition, it is important to note that a predisposition to misuse alcohol and develop dependence will only be expressed if a person consumes excessive amounts of alcohol. Here non-genetic familial factors are likely to play a major role.

Genes for alcohol dependence risk. Allelic association studies have focused in particular on the alleles of genes that affect alcohol metabolism because, as we have already seen, people with impaired activity of the alcohol-metabolizing enzyme, aldehyde dehydrogenase, have unpleasant reactions when they consume alcohol, and are therefore at significantly lower risk of alcohol dependence. At a molecular level, a point mutation in the gene for a form of aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2) renders the enzyme inactive; this mutation is less common in people with alcohol dependence. Subsequent linkage analyses have confirmed that mutations in the genes that code for aldehyde dehydrogenase protect against harmful drinking (Foroud et al., 2010). However, such mutations are rare in people of European ancestry. Other candidate genes have included the dopamine D4 receptor and the GABA receptor, and some associations with alcohol dependence have been reported. However, attempts at replication have yielded inconsistent findings. Similarly, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have not provided reliable indications of relevant genes, although again the GABA receptor has been implicated by some (Foroud et al., 2010).

Other biological factors

The sons of men with alcohol dependence are at increased risk of developing alcohol dependence themselves, and a number of studies have attempted to find biological abnormalities that may antedate and predict the development of alcohol dependence in these individuals. A variety of impairments have been described, including impaired performance on cognitive tasks, particularly executive function, and an abnormal P300 visual evoked response, which is a measure of visual information processing. There is also reasonably consistent evidence that sons of alcohol-dependent men are less sensitive to the acute intoxicating effects of alcohol. Presumably, if people experience less subjective response to alcohol, they may tend to drink more, thus putting themselves at risk of developing alcohol dependence. However, the evidence for this interesting hypothesis is inconsistent (Sher et al., 2005).

Learning factors

Alcohol use. Children tend to follow their parents’ drinking patterns, and from an early age boys tend to be encouraged to drink more than girls. Non-genetic familial factors appear to be important in determining levels of alcohol use. Nevertheless, it is not uncommon to meet people who are abstainers although their parents drank heavily. In addition, the risk of children of alcohol-dependent parents developing alcohol use disorders is apparently little influenced by whether their parents are currently drinking or not. This suggests that modelling of drinking behaviour does not contribute substantially to the increased risk in the children (Sher et al., 2005)

Reward dependence. It has also been suggested that learning processes may contribute in a more specific way to the development of alcohol dependence. Thus the ability of alcohol to increase pleasurable feelings and decrease anxiety could lead to behavioural reinforcement, particularly in people who for physiological or social reasons overemphasize the positive effects of alcohol while ignoring its negative consequences. Recent formulations that combine biochemical and cognitive approaches emphasize the role of dopamine release in mesolimbic pathways in mediating incentive learning. In this way drugs such as alcohol which increase dopamine levels in this brain region stimulate motivational behaviours that are focused on the need to secure further drug supplies. These behaviours may be outside conscious control, and are difficult to extinguish (Lingford-Hughes et al., 2010).

Personality factors

Little progress has been made in identifying personality factors that contribute to alcohol misuse and dependence. In clinical practice it is common to find that excessive alcohol consumption is associated with chronic anxiety, a pervading sense of inferiority, or self-indulgent tendencies. However, many people with personality problems of this kind do not resort to excessive drinking or become alcohol dependent. Other surveys have emphasized the role of personality traits that lead to risk taking and novelty seeking (Kampov-Polevoy et al., 2004). It seems likely that these characteristics apply to those with antisocial personality disorder, who are known to be at increased risk of misusing alcohol and developing alcohol dependence. However, the majority of alcohol-dependent people do not have an antisocial personality disorder.

Psychiatric disorder

Alcohol misuse is commonly found in conjunction with other psychiatric disorders, and sometimes appears to be secondary to them. For example, some patients with depressive disorders use alcohol in the mistaken hope that it will alleviate low mood. Those with anxiety disorders, particularly panic disorder and social phobia, are also at risk. Alcohol misuse is also seen in patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. The mechanisms underlying this comorbidity are not established, but overlapping genetic predispositions are a possibility, perhaps associated with shared abnormalities in the functioning of reward pathways (Negrete and Gill, 2009). (The treatment of patients with severe mental illness and comorbid substance misuse is discussed on p. 471).

Alcohol consumption in society

There is now general agreement that rates of alcohol dependence and alcohol-related disorders are correlated with the general level of alcohol consumption in a society. Previously it had been supposed that levels of intake among excessive drinkers were independent of the amounts taken by moderate drinkers. The French demographer Ledermann (1956) challenged this idea, proposing instead that the distribution of consumption within a homogeneous population follows a logarithmic normal curve. If this is the case, an increase in the average consumption must inevitably be accompanied by an increase in the number of people who drink an amount that is harmful.

Although the mathematical details of Ledermann’s work have been criticized, there are striking correlations between average annual alcohol consumption in a society and several indices of alcohol-related damage among its members. For this reason, it is now widely accepted that the proportion of a population that drinks excessively is largely determined by the average alcohol consumption of that population.

What then determines the average level of drinking within a nation? Economic, formal, and informal controls must be considered. The economic control is the price of alcohol. There is now ample evidence from the UK and other countries that the real price of alcohol (i.e. the price relative to average income) profoundly influences a nation’s drinking habits. Furthermore, heavy drinkers as well as moderate drinkers reduce their consumption when the tax on alcohol is increased.

The main formal controls are the licensing laws, but these do not seem to influence drinking behaviours in a consistent way when comparisons are made between different countries. Informal controls are the customs and moral beliefs in a society that determine who should drink, in what circumstances, at what time of day, and to what extent. Some communities appear to protect their members from alcohol misuse despite the general availability of alcohol. For example, alcohol-related problems are uncommon among Jews even in countries where there are high rates in the rest of the community. For a discussion of the economic and social aspects of alcohol consumption, see the Academy of Medical Sciences (2004).

Recognition of alcohol misuse

Detection

Only a small proportion of alcohol misusers in the community are known to specialized agencies. When special efforts are made to screen patients in medical and surgical wards, around 10–30% are found to misuse alcohol, with the rates being highest in Accident and Emergency wards. It has been estimated that of the one million people in England who are dependent on alcohol, only about 6% a year receive treatment. There are probably several reasons for this, including lack of help seeking by users, limited availability of specialist alcohol services, and under-identification of alcohol misuse by health professionals (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2011a).

Screening questionnaires. Alcohol misuse often goes undetected because patients conceal the extent of their drinking. However, doctors and other professionals often do not ask the right questions. It should be a standard practice to ask all patients (medical, surgical, and psychiatric) about their alcohol consumption. Brief screening questionnaires can be helpful—for example, the CAGE questionnaire which consists of the following four questions.

• Have you ever felt you ought to Cut down on your drinking?

• Have people Annoyed you by criticizing your drinking?

• Have you ever felt Guilty about your drinking?

• Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning (an ‘Eye-opener’) to steady your nerves or get rid of a hangover?

Two or more positive replies are said to identify alcohol misuse (see p. 125). Some patients will give false answers, but others find that these questions provide an opportunity to reveal their problems. Overall the CAGE has a good sensitivity but only modest specificity (Warner, 2004).

An alternative is the AUDIT, a 10-item structured interview designed at the request of the World Health Organization for screening for both currently harmful and potentially hazardous drinking. It shows good sensitivity and specificity, can identify mild dependence, and is probably the most useful screening questionnaire for clinicians and researchers in primary care (see Box 17.2).

Scores for each question range from 0 to 4, with the first response for each question scoring 0, and the last response scoring 4. For questions 9 and 10, which only have three responses, the scoring is 0, 2, and 4.

People who score in the range 8–15 should receive a brief intervention based on their risk for developing alcohol-related harm. Those who score 16–19 need a brief intervention and regular monitoring, including referral to specialist alcohol services if heavy drinking continues. Those who score in the range 20–40 should receive an early specialist referral and, depending on the severity of physical dependence, detoxification and other treatments (Room et al., 2005).

General ‘at-risk’associations. The next requirement is for the doctor to be suspicious about ‘at-risk’ associations. In general practice, alcohol misuse may come to light as a result of problems in the patient’s primary relationship and family, at work, with finances, or with the law. The alcohol misuser is likely to have many more days off work than the moderate drinker, and repeated absences on a Monday should arouse strong suspicion. The high-risk occupations (see p. 448) should also be borne in mind.

Medical ‘at-risk’ associations. In hospital practice, the alcohol-dependent patient may be noticed if they develop withdrawal symptoms after admission. Florid delirium tremens is obvious, but milder forms may be mistaken for an acute organic syndrome—for example, in pneumonia or post-operatively. In both general and hospital practice, at-risk factors include physical disorders that may be alcohol related. Common examples are gastritis, peptic ulcer, and liver disease, but others such as neuropathy and seizures should be borne in mind. Repeated accidents should also arouse suspicion.

Psychiatric at-risk associations include anxiety, depression, erratic moods, impaired concentration, memory lapses, and sexual dysfunction. Alcohol misuse should be considered in all cases of deliberate self-harm.

Drinking history

If any of the above factors raise suspicion of alcohol misuse, the next stage is to take a comprehensive drinking history (see Box 17.3). This should be done sensitively, with understanding that the patient may have difficulty in giving a clear history. The clinician should aim to build up a picture of what and how much the patient drinks throughout a typical day—for example, when and where they have the first drink of the day. The patient should be asked how they feel if they go without a drink for a day or two, and how they feel on waking. This can lead on to enquiries about the typical features of dependence and the range of physical, psychological, and social problems associated with it.

To gain an idea of the duration of alcohol problems, key points in the history may include establishing when the patient first began drinking every day, when they began drinking in the mornings, and when, if ever, they first experienced withdrawal symptoms. It is useful to ask about periods of abstinence from alcohol, what factors helped to maintain this state of affairs, and what led to a resumption of drinking. This can lead on to enquiries about past attempts at treatment.

It is necessary to obtain a clear understanding of the patient’s own view of their drinking behaviour, because there are a number of possible treatment goals. In this situation the patient’s attitude to their problems plays a key role in deciding which approaches are likely to be most beneficial (see the section on motivational interviewing).

Laboratory tests

Several laboratory tests can be used to detect alcohol misuse, although none gives an unequivocal answer. This is because the more sensitive tests can give ‘false-positive’ results when there is disease of the liver, heart, kidneys, or blood, or if enzyme-inducing drugs such as anticonvulsants, steroids, or barbiturates have been taken. However, abnormal values point to the possibility of alcohol misuse. The most useful tests are listed in Box 17.4.

The treatment of alcohol misuse

Early detection and treatment

Early detection of excessive consumption of alcohol and alcohol misuse is important because treatment of established cases is difficult, particularly when dependence is present. Many cases can be detected early by general practitioners, physicians, and surgeons when patients are seeking treatment for another problem (see Box 17.5).

Brief intervention

General practitioners are well placed to provide early treatment of alcohol problems, and they are likely to know the patient and their family well. It is often effective if the general practitioner gives simple advice in a frank, matter-of-fact way, but with tact and understanding.

Brief intervention approaches generally involve simple education and advice about safe levels of alcohol consumption. The aim is to promote safer drinking, rather than abstinence. Generally, brief interventions lead to a significant reduction in alcohol consumption over the next few years, and are the best initial approach for a person whose alcohol consumption exceeds safe limits. It is generally agreed that brief interventions are not effective for people with severe drinking problems, particularly those who are alcohol dependent (Boland et al., 2008).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree