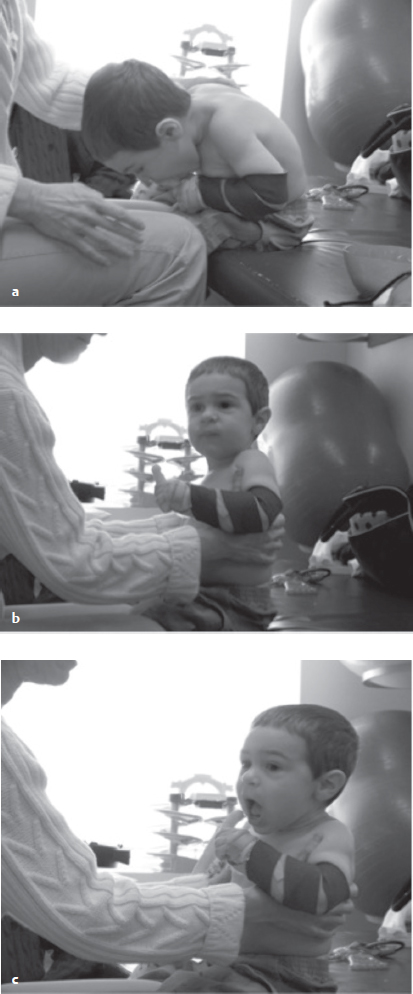

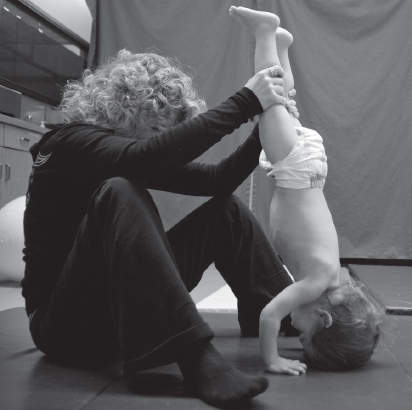

16 The Practice of Occupational Therapy from a Neuro-Developmental Treatment Perspective This chapter examines the role of occupational therapy, providing the reader with an understanding of sensory processing, arousal and attention, play, and activities of daily living within the Neuro-Developmental Treatment (NDT) Practice Model. Alternately, NDT as a frame of reference within occupational therapy emphasizes the analysis and understanding of impaired posture, movement, body structures, and functions in the neurologically challenged individual. Clinical examples throughout the chapter demonstrate how merging the knowledge bases of occupational therapy and NDT can enhance outcomes for the activities and participation domains of neurologically challenged individuals. Learning Objectives Upon completing this chapter the reader will be able to do the following: • Define who an occupational therapist (OT) is in terms of professional responsibilities and functional outcomes addressed in client management. • List at least three skills NDT education enhances in the professional skills of OTs. • Analyze an occupational therapy outcome with a specific participation or activity of a client in his or her own practice using the NDT Practice Model. The partnership of Neuro-Developmental Treatment (NDT) and occupational therapy is a marriage of perfection. At the heart of this merger between NDT and occupational therapy are a set of complementary principles and a shared philosophy, both intending to optimize human occupation and function. Specialized knowledge fundamental to NDT expands the OT’s professional skills, thereby enhancing intervention for this target population. The World Health Organization (WHO)1 definition of occupational therapy identifies the OT as using careful analysis of physical, environmental, psychosocial, mental, spiritual, political, and cultural factors to identify barriers to occupation. Whether the individual is an adult or a child, the therapist enhances occupational performance by addressing individual needs through direct intervention, modifying the environment, or changing the requirements of the task. As a profession, occupational therapy began in the early 1900s. OTs initially worked to help wounded soldiers of World War I. Over time, the occupational therapy profession evolved, and in the years between the 1940s and 1960s, OTs thrived during the period referred to as the rehabilitation movement. OTs were called on not only to organize and run programs for the wounded military personnel but also to provide care for those who previously would not have lived without advanced medical sciences to help treat spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and cerebral palsy. OTs were first introduced to the work of Dr. and Mrs. Bobath in the 1960s. Even in the early stages of their theory, the Bobaths recognized the importance of the interdisciplinary approach. The concepts taught by the Bobaths have long been embraced by OTs worldwide. Schleichkorn indicated, “It is felt that, apart from their treatment, one of the major contributions of Dr. and Mrs. Bobath has been in helping to break down the artificial barriers which have existed for too long between the disciplines of physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy.”2 The foreword of Eggers’s book, Occupational Therapy in the Treatment of Adult Hemiplegia, written by Karel and Berta Bobath states, “It requires team-work and the close collaboration of physiotherapists, speech therapists and occupational therapists. We have long awaited this book, which meets a need in the area of total management by relating physiotherapy and occupational therapy. It will be of special value to occupational therapists who are working in hospitals where each member of the team follows the same concept and principles.”3 Eggers goes on to say, “This concept, which was developed for physiotherapists, can, and in my opinion, be well incorporated into occupational therapy because it has the facilitation of normal movement sequences, which are necessary for all activities of daily living, as the goal.”3 An American OT, Judy Murray, who resided in London and had conversations with the Bobaths, merged the concepts of activities of daily living (ADLs), play, vision, sensory, perceptual, and adaptive equipment into the NDT treatment approach. Mechthild Rast, an NDTA-certified OT instructor, also helped shape the original theory by incorporating the importance of upper extremity performance and play as the work of the child. These early roots of occupational therapy have influenced, and continue to influence, the NDT curriculum, accentuating the holistic team approach within NDT intervention. Therapists treating children will most likely examine the occupations of play, education, rest and sleep, ADLs, instrumental ADLs (IADLs), and social participation. Occupations for adults include employment, child and family care, leisure, ADLs, IADLs, social participation, and an array of other activities performed throughout the day. Each of these human occupations can be evaluated and treated through an NDT lens, emphasizing the posture and movement components of each function. NDT, being a dynamic hands-on intervention practice model, guides the OT globally in the evaluation of and intervention for children and adults with neurological impairment. Being a client-centered approach, NDT promotes an individualized problem-solving framework of clinical reasoning and analysis for managing identified impairments. Guided by the WHO’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), an OT using the NDT Practice Model will examine body functions and structure and the domains of activity and participation, identifying what tasks the individual has not yet learned to do or is no longer able to accomplish. Layers of depth are then added to the examination by identifying specific impairments within the motor and body structure domains that may include neuromotor, cognitive, perceptual, and sensory systems influencing social and individual functions. Observation, analysis, and intervention for function are fundamental principles of occupational therapy, requiring the therapist to develop hypotheses about behaviors, which guides clinical reasoning and intervention planning. Distinctly, NDT highlights the analysis of typical movement and its progression across the life span, helping the OT develop theories about why individuals with neuropathology move the way they do within an occupation or an activity. The emphasis on analysis of typical movement is embedded in the NDT Practice Model because typical movements are the most efficient movements leading to the possibility of more complex movement patterns. As discussed in Chapters 2 and 14, NDT does not expect clients to gain or regain all typical movements; rather, therapists seek to develop more efficient motor skills within the individual’s capabilities that also minimize impairments in body systems. For example, in typical adult reach, the action is initiated with a visual gaze to the target with the eyes focused, the hand opening, and the arm following the direction of the hand motion. Reach may also involve the trunk and legs, even in sitting, when reach demands movement of the center of mass over the base of support. Following a stroke, the individual may initiate this action with scapular elevation, humeral abduction, and internal rotation, and lack control of the hand position, with the pelvis dropped into a posterior pelvic tilt position as seen in Fig. 16.1. Children with neurological pathology may also exhibit atypical patterns of reach. The child may attempt to bring his arm forward by laterally flexing his trunk, elevating his shoulder girdle, internally rotating the shoulder, hyperextending the elbow, pronating the forearm while extending the wrist, and fisting his hand when reaching toward the object of desire as seen in Fig. 16.2. In both examples atypical body structure and function patterns such as these significantly alter the effectiveness of reach in forward space to interact with an object or the environment. The NDT frame of reference also deepens the OT’s knowledge of compensatory and atypical movement patterns that arise from primary and secondary impairments. Whether providing intervention to children or adults with neurological impairments, OTs need to understand how and why atypical movement patterns develop following neuropathology. Fig. 16.1 To raise her left arm poststroke this individual weight shifts to the left, lengthens and posteriorly rotates her trunk on the left, and rotates and extends her neck. The humerus moves into horizontal abduction and internal rotation. Evident threads of repeating movement impairments will be illuminated as the therapist analyzes and observes the effects of varying gravitational and biomechanical forces involved in movement sequences, motor planning demands, environmental requirements, and quality of movement sequences themselves. For example, when a child or adult with hemiplegia moves from sit to stand to answer a telephone, she may shift her weight to her less involved body side and push up to stand with the less involved arm, paying little, if any, attention to the more neurologically involved side of her body. The OT using the NDT framework of practice would have an appreciation of both the most efficient and possibly atypical movement sequences involved in the sit to stand movement, providing the therapist with knowledge to develop therapeutic intervention strategies. The therapist may use select handling strategies to alter the alignment of the individual’s body over her base of support in relationship to the forces of gravity prior to and during the sit to stand movement sequence to facilitate a more efficient and functional movement pattern. Handling strategies are used to decrease the use of excessive muscle force employed to stabilize body segments, compensations used to hold the person up against the forces of gravity. Gradual withdrawal of facilitation occurs as the individual assumes increased internal control of her movements, activating and modulating her own muscle forces. The NDT-educated OT may also alter the environmental or task demands to influence the posture and movement choices. For example, having the individual stand from a higher surface initially may place less demands on motor control, thus increasing the likelihood of successful movement patterns. In addition, having individuals reach forward and up with the less involved hand for a desired object may offer insights to the impairments interfering with the earlier attempts. When evaluating occupations, the OT using the NDT Practice Model emphasizes the analysis of the client’s posture and movement strategies by combining observation of motion and palpation of muscle and postural tone while the individual is both at rest and in action. While observing task performance, the OT using the NDT Practice Model evaluates both the individual’s movement competencies and the single and multisystem impairments. Special attention is directed to the postural alignment and the interaction of the body systems. Joint range of motion, postural control over a base of support, and synergies of motor action are examples of posture and movement components evaluated within the context of an occupational task.4 Intervention within the NDT frame of reference provides individuals experiencing neurological impairment with the opportunity to experience or reexperience efficient movement within the context of function. The artful skill of handling is a powerful and unique tool central to the NDT process. Through graded external manual guidance provided by the NDT-educated therapist’s contacts and body movements, the individual with neuropathology receives input that emulates the feeling and embodiment of more efficient posture and movement components. With their hands on the individual, NDT therapists feel and perceive the individual’s anticipatory movements and bodily responses to changes in posture and movement, facilitate and expand an individual’s postural control and movement strategies, inhibit movements that interfere with task performance, and constrain movements that may lead to secondary impairments over time. Moment by moment sensory feedback between the individual and the therapist informs the clinical reasoning process and guides the therapist in grading the handling, changing the hand placement, giving the directional cues, and gauging the intensity of sensory input provided. The examination and intervention are woven seamlessly together as part of the holistic perspective of NDT intervention. When, why, and how handling is employed within an NDT session is a fluid progression based on this interchange between the therapist and the individual with neuropathology. As the individual acquires increasing movement competence, handling is faded and eventually removed from the intervention process, decreasing reliance on the therapist as seen in Fig. 16.3a–c. This unique handling and clinical reasoning skill set rooted in NDT is a powerful adjunct to the practice of occupational therapy for individuals experiencing neurological impairment. Within the context of NDT, individuals with neuropathology are not expected to improve function by simply practicing a skilled activity over and over again using their existing impaired posture and movement strategies. Individuals experiencing neurological impairment do not consistently have the capacity to autonomously select or activate appropriate motor patterns necessary for independent task performance. Fig. 16.3 (a) This child eats Cheetos by bringing his mouth to his hand when attempting to feed himself. (b) Hand to hand compression through the rib cage and down to the base of support to activate hip extensors. (c) Compression directed through the rib cage down toward the base of support to activate the postural system musculature to support the child in bringing his hand to his mouth while feeding himself a Cheeto. Historically, occupational therapy has been identified within the health care community as the discipline dedicated to promoting independence in functional tasks or occupations. The OT is educated in the ability to break down a skill set into subskills and to analyze the components of the task (occupation) and the environment. Subsequently, the NDT-educated OT carefully selects therapeutic activities and specific subtasks of the activities to address the individual’s impairments through task analysis, avoiding the possibility of excessive effort, which may result in overrecruitment of atypical and less efficient posture and movement strategies. For example, when working with a child with neurological impairments, the therapist may identify core musculature weakness as a primary impairment. Selection of a therapeutic activity, such as drawing in shaving cream on a mirror while sitting on a moving surface, may activate and strengthen the deep postural muscles while the child works to control the movements of her upper extremities in space. OTs are professional experts in task analysis. The movement analysis skills embedded in the NDT frame of reference enhance the OT’s existing ability to scrutinize motor components of the task. With this additional knowledge afforded by the NDT Practice Model, the OT is better able to select the appropriate subtask, work surface, base of support, and tool use to capitalize on the movement-learning opportunity for the individual and to address the individual’s specific impairments. For example, by having a child draw on a vertical mirror as opposed to a horizontal work surface, such as a table, the orientation of the activity in space discourages the child from collapsing into a less efficient postural strategy of trunk flexion. The nature of reaching for and drawing in the transverse plane of movement demands a postural control strategy that asks for activation of postural muscles to work against the forces of gravity. OTs using the NDT Practice Model also employ their task analysis skills when treating the adult with neurological challenge. For example, in the task of baking, the subtask of kneading dough may be the intervention activity chosen, with the intention to promote typical posture and movement strategies and to address the individual’s underlying impairment of weakness of the abdominal oblique muscles. With thorough analysis of the adult client’s required posture and movement patterns, the OT could alter the environment and task components, such as the use of stiff dough placed on a slightly inclined or high counter with the client in a standing position. While an individual participates in a task, the therapist provides handling to the postural system while continuously modifying the environment and the task, facilitating or inhibiting muscle synergy patterns to develop autonomous control of the movements necessary for function. Although handling is a significant component of NDT, continual evaluation and alteration of the environment and task ensure that the individual is appropriately challenged within the activity selected. Repetition with variety, along with practice at home, school, work, or play, supports carryover of newly acquired movements. The OT brings to the NDT Practice Model a specialization in understanding the sensory processing contributions to posture and movement. Neurologically challenged individuals are often unable to appropriately detect and identify sensory information, which can result in significant deficits in motor control. Sensory data are coded and stored within the nervous system, providing a reference point or map of the body, space, and how the body moves within the spatial array.5 Previously learned movements and whole functional skills are stored in motor memory, relying on precise sensory processing for future analysis, comparison, and movement production. Any interruption in the detection, coding, or interpretation of single-sensory or multisensory information can give rise to maladaptive postural orientation or movement. When the body map is impoverished or unpredictable, individuals with neurological impairment will have difficulty knowing where their body is in space, which muscles to recruit, how much force to enlist, how to coordinate synergies of muscles together, and how to move the body within the environment.6 Previously experienced sensation from body movements provides individuals with feed-forward capacity, a backdrop pulse of neuromuscular activity preparing postural set, getting an individual ready to move.7 Interference within the sensory processing systems may result in challenges with anticipatory posture and movements as well as sensory feedback from movements necessary for functional performance. The tactile, proprioceptive, and vestibular sensations are processed at multiple levels throughout the nervous system, contributing to motion, perception, emotion, and cognition. Individuals may experience oversensitivity or underresponsiveness to these body senses, resulting in either an overmagnification of sensory perception or a minimization of sensory experiencing.5 For example, a child with tactile sensitivity may find textures, clothing, light touch, or unexpected touch to be painful or uncomfortable, often evoking an emotional response. Adults with TBI, neuropathology, or central nervous system impairments may also experience tactile sensitivity interfering with their function and the learning of new movements. During an experience of tactile sensitivity, the fight–flight–fright pathway in the autonomic nervous system may be triggered into a heightened state of threat, preventing the individual from feeling safe to explore or experience touch in a relaxed and comfortable way.6 When discomfort to touch is evident, an individual may limit exploration of movement and the environment. Handling components of NDT intervention may be rejected or resisted by the tactilely sensitive individual, altering full participation in the intervention process. Therapists must pay close attention to the depth of touch during handling, minimizing the speed and frequency with which they change key points of control while monitoring the individual’s stress response to handling. Handling with deep-pressure touch can help to mitigate sensitivity to touch, organizing an individual’s overall state of arousal and making touch experiences less frightening.6,8 OTs working within an NDT framework integrate intervention strategies based on their sensory processing knowledge to help modulate tactile processing issues. Deliberate and mindful provision of deep-pressure touch to an individual’s body is typically perceived as a calming and organizing stimulus. The appreciation of deep-pressure touch as a sensory tool merges elegantly with NDT principles of handling. Inhibition of tactile sensitivity and facilitation of tactile responsiveness are underpinnings of and parallel processes to the NDT practice model.6 Alternately, individuals with neurological impairment may also experience an underresponsiveness to touch. Individuals who do not perceive or feel tactile stimuli may crave touch, with excessive exploration of the tactile environment. Many individuals who are underresponsive to touch mouth objects, seek out messy play, and typically enjoy intense sensations like vibration. Underresponsivity can be observed in both children and adults with neurological challenge. Following a stroke, for instance, many individuals experience absent or decreased sensory awareness of their hemiplegic body side. Limited awareness of the body parts affects muscle recruitment, initiation, activation, and movement of that body part as it moves in space. Tactilely enriched and sensory demanding activities, such as playing with shaving cream (Fig. 16.4), finger painting, sand play, and walking in bare feet, accentuate the tactile sense, alerting the brain to this component of the sensory array. Intervention for adults experiencing neurological challenge may similarly load the tactile system with emphasis to increase body awareness and feedback to the movement system. Many tasks introduced during intervention with adults should demand bimanual or bilateral (Fig. 16.5) use to highlight attention to the affected arm and the task or have a consequence, such as water spilling from the cup if the hand/arm does not hold it upright. Proprioceptive processing and vestibular processing are also frequently altered by neuropathology, affecting the substrates of motor control.9 The vestibular system provides information about gravity, direction, and speed of movement in space and sends information to the muscles of postural control, responding to perturbations in balance and equilibrium. Overresponsiveness to vestibular information can leave individuals feeling dizzy, ungrounded, and lost in space, challenging their relationship to the forces of gravity. This type of overresponsiveness, if not addressed in intervention, can be tremendously disruptive to learning and experiencing movement within the NDT intervention process. OTs typically label this type of sensory processing challenge gravitational insecurity.5 When experiencing gravitational insecurity, the individual will experience movement off the support surface as terrifying, especially movements in backward space. Individuals may become tense and hold their body stiffly in a guarding fashion to counteract the sense of falling or feeling out of control. By facilitating movements that are grounded on the support surface, which can be slow moving, in a linear direction, and combined with deep-pressure touch, the therapist provides the individual with gravitational insecurity so that he can learn over time to feel safe with movement in space (Fig. 16.6). Fig. 16.5 Bilateral tasks, such as carrying heavy items, are used to increase attention and place demands on the more involved side. This helps with increasing perceptual, tactile, and proprioceptive awareness. For adults with neuropathology who may also experience vestibular impairments, movement can be challenging. Atypical movement patterns can develop from the individual’s fear of falling or altered sense of midline. Some strokes insult the vestibular system directly, creating central nervous system vestibular disturbances. The vestibular system can also be damaged peripherally by head trauma, infection, or damage to the labyrinth itself. Symptoms of vestibular dysfunction can include benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), dizziness, motion sickness, and nystagmus, which result in significant functional impairment. Many individuals are so profoundly disturbed by vestibular challenges that they are unable to roll over in bed without experiencing incapacitating symptom-atology. Fatigue and stress responses with anxiety frequently accompany vestibular limitations, requiring immediate intervention with emphasis on the correction of vestibular processing prior to the initiation of handling and movement. When evaluating motion sensitivity, the therapist must identify the specific movements in space that induce dizziness. Specific maneuvers of the vestibular rehabilitation protocol may be introduced to potentially alleviate the limiting symptomatology, helping the individual habituate to the vestibular disturbance. It is important not to wait until vestibular symptoms resolve before initiating NDT intervention. For the adult client, a fear of falling forward, especially during the acute stages of recovery, often results in an atypical pattern of movement of leaning to one side or pushing backward to find a sense of centeredness. This compensatory attempt at centeredness may produce a postural bias away from or toward the weaker side of the body, dependent upon the location of the stroke lesion. Alternately, many children and adults with neurological impairment are underresponsive to vestibular and proprioceptive sensation. Individuals who present with a high threshold to vestibular and/or proprioceptive sensations present as either hypotonic, low arousal, under-responsive individuals, or individuals who actively seek movement, or who enliven in arousal, alertness, and postural activation when they are engaged in a movement activity. The vestibular nuclei may not receive sufficient input, resulting in an impoverished message down the spinal cord to the muscles that extend the neck, arms, back, and legs. Individuals may have trouble holding their head up while sitting, or they may become easily fatigued when working against gravity.5 The postural systems of underresponsive individuals need enhanced vestibular/proprioceptive data to perceive and respond to alterations in space. Careful examination of this system allows the NDT-educated OT to accentuate movement opportunities with differing speeds, direction, and demands, combined with proprioceptive input to open the nervous system’s capacity to sense and produce posture and movement. Movement on the therapy ball, swings, rolls, and other moving surfaces can offer a multitude of sensory opportunities that emphasize vestibular/proprioceptive input for the child (Fig. 16.7). For the adult, vertical postures of high sitting and supportive standing can stimulate the reticular activating system through the vestibular sense, increasing overall arousal and alertness. The incorporation of moving surfaces that are functionally relevant to the adult client, such as a rolling office chair, an escalator, a treadmill, a moving walkway, can also be used to enhance the nervous system’s ability to sense and produce posture and movement. Sensory input from the somatosensory systems converges with visual and auditory information at varying levels throughout the brain, increasing integration and perception in preparation for action. Together, visual and auditory sensations help to drive the movement system, help to map environmental space, and orient the body within the spatial array. Visual and vestibular system information merges in the brainstem, collaborating to stabilize visual gaze, maintain a stable visual horizon, and orient the eyes in relationship to a target. Accurate reception of vestibular input is necessary for optimum eye muscle recruitment, observed when visually tracking and employing saccadic eye movements. Limitations in either the vestibular or the visual system alter the function of their partnership due to the integrated nature of their interaction.

16.1 The Occupational Therapy Profession

16.2 Occupational Therapy and Neuro-Developmental Treatment

16.2.1 Task Analysis

16.2.2 Examining, Evaluating, and Intervention of Sensory Processing for Function

Tactile, Vestibular, and Proprioceptive Processing

Visual and Auditory Processing

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree