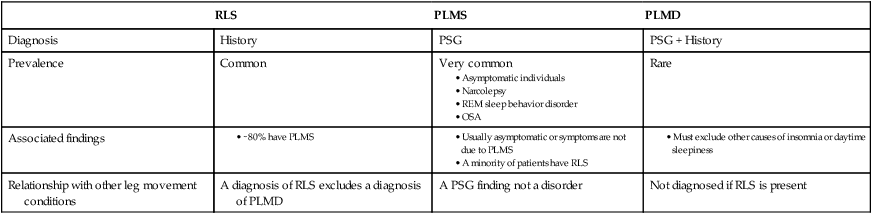

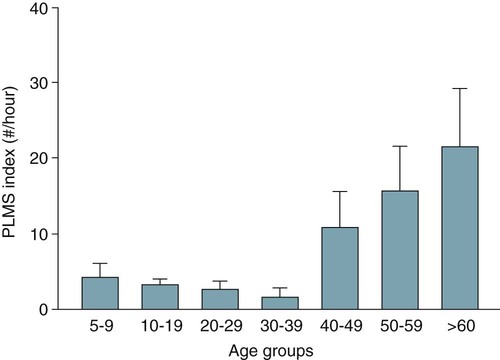

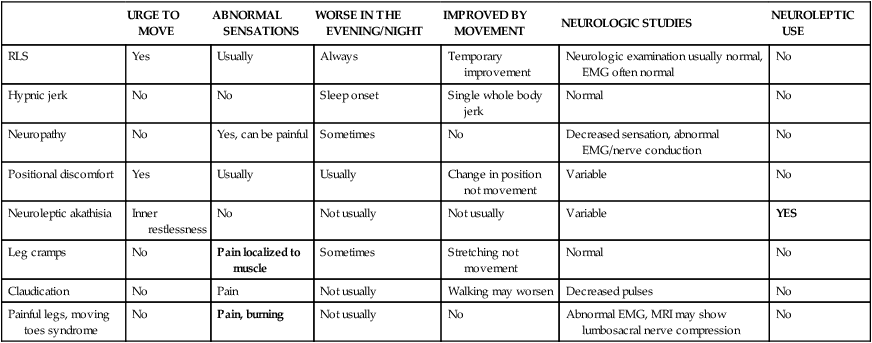

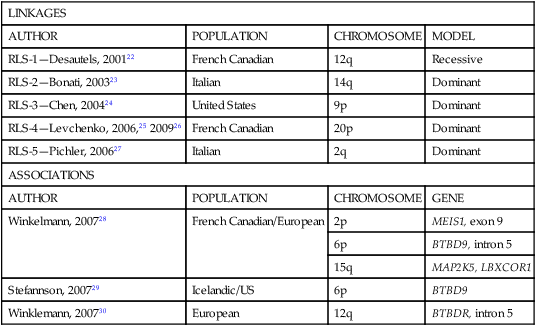

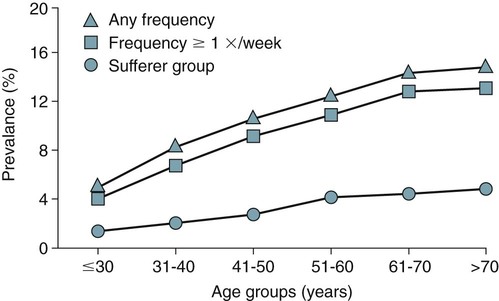

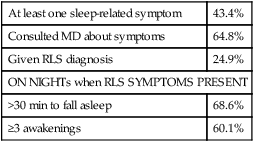

• A diagnosis of the RLS is based on clinical history. The essential elements include URGE (Urge to move, Rest makes symptoms worse, Gets better with movement—temporary improvement in symptoms with movement, and Evening is worse [symptoms worse in the evening, at least at the onset of the syndrome]). • Supportive clinical features for the diagnosis of RLS include a family history, improvement with dopaminergic treatment, and the presence of PLMS on PSG. • Secondary causes of RLS included renal failure, pregnancy, iron deficiency, and medications. Medications frequently worsening RLS include first-generation antihistamines, antidepressants (except bupropion), and dopamine blockers (phenothiazines, metochlopramide). • A diagnosis of PLMD is based on both history and PSG findings: (1) A complaint of sleep disturbance or daytime fatigue, (2) PSG findings PLMSI > 5/hr (children) and > 15/hr in adults, (3) Symptoms are not better explained by another sleep, medical, or neurologic disorder, or medication use (e.g., OSA). A diagnosis of RLS excludes a diagnosis of PLMD. A complaint of sleep disturbance must be made by the patient (in contrast to the bedmate). • PLMS is a PSG finding. PLMS is very common in older adults and is most often asymptomatic. PLMS can be associated with OSA, narcolepsy, and RBD. • About 80% of patients with RLS will have a PLMS index ≥ 5/hr on PSG. • The PLMD may precede a diagnosis of RLS in children. A diagnosis of RLS is difficult in children because they may not report traditional symptoms. They may present with “growing pains.” • Treatment options for RLS include conservative measures, dopaminergic medications (LD/CD and DAs), anticonvulsants, opiates and opioid agonists, and sedative hypnotics. • LD/CD is a rapidly absorbed dopaminergic medication (LD is a precursor of dopamine) that is effective treatment of RLS. It is a good option for intermittent RLS. However, the medication has a short duration of action and continued use results in augmentation in up to 80% of cases (especially with doses of LD > 200 mg daily). • The DAs ropinirole and pramipexole are FDA approved for treatment of RLS in adults and are considered the treatment of choice for daily RLS. They must be given 2 hours before symptoms to be most effective. • Anticonvulsants are also effective for RLS/PLMD. Due to a good safety profile, gabapentin is the anticonvulsant recommended for RLS treatment. Doses of 900 to 1500 mg of gabapentin may be needed to be effective. A slow upward titration of the dose starting at 300 mg may improve tolerance to use. Gabapentin is considered a first-line medication by some clinicians if RLS is associated with pain. • Narcotics are effective treatment for RLS. They may be especially useful in patients who develop augmentation or do not tolerate DAs. If given only at bedtime, they usually do not result in dependence. For milder cases, codeine, propoxyphene, or tramadol may be effective. For moderate RLS, hydrocodone (combined with acetaminophen in the United States) or oxycodone is often used. For severe RLS, oxycodone or methadone has been used with success. • Sedative hypnotics may be useful in milder RLS associated with insomnia or can be combined with other classes of medications. Most of the published treatment trials used clonazepam (long half-life), but other BZRAs may also be effective. • Augmentation describes a phenomenon that is characterized by one or more of the following: (1) earlier symptom onset, (2) greater severity of symptoms at the same dose/or escalating dose, (3) reduced latency to onset of symptoms with rest, and (4) spread of symptoms to involve new body parts (arms as well as legs). • Low serum ferritin (<45 to 50 µg/mL) is a risk factor for development of augmentation. • RLS patients with a ferritin less than 45 to 50 µg/mL may improve with iron supplementation. The usual dose is ferrous sulfate 325 mg tid with each dose given with 100 to 200 mg of ascorbic acid to improve absorption. Patients with augmentation may improve with iron supplementation. The restless legs syndrome (RLS), periodic limb movements in sleep (PLMS), and the periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) are three distinct but related entities1–6 (Table 23–1). A diagnosis of RLS is based on clinical history. PLMS is a polysomnography (PSG) finding that may or may not be clinically important. The PLMD is diagnosed in patients with PLMS on PSG who have a sleep complaint (sleep-onset or maintenance insomnia or, less commonly, daytime sleepiness) not better explained by another sleep disorder.6 PLMS is a very common finding especially in older patients (Fig. 23–1) and is often asymptomatic.5,7–11 Approximately 80 to 90% of patients with RLS will have findings of PLMS on PSG.12 The percentage of patients with PLMS who have RLS has not been well-defined, but the vast majority of patients with PLMS do not have RLS. PLMS has been associated with narcolepsy, the REM sleep behavior disorder, and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). A diagnosis of RLS excludes PLMD. PLMS is very common, RLS is common, and PLMD is thought to be rare. Chapter 12 outlines the scoring criteria for PLMS in detail with examples of illustrative tracings. This chapter emphasizes the clinical significance of PLMS. TABLE 23–1 Different Leg Movement Conditions The RLS is a common disorder often underdiagnosed and improperly treated. In 1995, the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG)11 published a statement on the primary and associated features of the syndrome. The criteria were refined during a workshop at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).13 The criteria form the basis for the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 2nd edition (ICSD-2) diagnostic criteria for RLS6 (Box 23–1). There are four essential diagnostic criteria for RLS (URGE = urge to move, rest induced, gets better with activity, evening and night worse). 1. The patient reports an urge to move the legs, usually accompanied or caused by uncomfortable and unpleasant sensations in the legs. Of note, the urge to move can be present without associated symptoms. Commonly reported RLS sensations are listed in Box 23–2. Although called the “restless legs syndrome,” symptoms can occur in the arms as well as the legs in 30% to 50% of the patients.12,13 Although RLS symptoms are usually bilateral, some patients report symptoms mainly in one extremity.12 About 20% of RLS patients report the leg sensations to be painful. Involuntary leg movements may also be reported without an urge to move (“the legs just move on their own”). As discussed later, this is a manifestation of periodic limb movements during wake (PLMW). 2. RLS symptoms begin or worsen during periods of inactivity such as lying or sitting. Being stationary and having decreased mental activity appear to both worsen symptoms. 3. The urge to move or unpleasant sensations are totally or partially relieved by movements such as walking or stretching as long as the activity continues (temporary relief). Rubbing the legs or taking hot or cold baths may improve symptoms in some patients. Of note, increased mental activity or eating can improve the symptoms (“popcorn therapy” while watching a movie). 4. The urge to move or unpleasant sensations are worse in the evening or night. If RLS has become very severe, nocturnal worsening may not be reported but should have been present earlier in the disease course. When RLS is severe, daytime symptoms can occur especially during periods of inactivity. Some patients will report atypical symptoms.13 The supportive clinical features of RLS (Box 23–3) may help resolve diagnostic uncertainty. They are not required for a diagnosis of RLS. In studies of groups of patients with RLS, a familial history is reported in 50% to 60% of the cases. A family history of RLS is supportive of the diagnosis. An improvement with a trial of dopaminergic treatment is also evidence that symptoms represent the RLS. However, one must be aware of the placebo effect. Placebo-controlled studies in RLS report considerable improvement in symptoms with inactive medication. The periodic limb movements in sleep index (PLMSI) is defined as the number of periodic limb movements (PLMs) per hour of sleep. The criteria for scoring a leg movement as a periodic leg movement are discussed in Chapter 12. It is difficult to define a normal PLMSI (see Fig. 23–1). In the past, some sleep centers considered a PLMSI of 5/hr or greater to be abnormal. However, many asymptomatic individuals have much higher PLMSI values,7–9 The presence of PLMS can provide supporting evidence for the presence of the RLS. One study employing a PLMSI cutoff of 5/hr reported that 80.2% of patients with RLS had PLMS (87% if 2 nights were monitored).12 Patients with RLS often report repetitive involuntary leg movements during wakefulness when at rest especially at night. This is a manifestation of PLMW (periodic limb movements during wake). The differential diagnosis of RLS/PLMS includes a number of mimics13–16 (Table 23–2 and Box 23–4). Most of these are not associated with an urge to move. Often, the movements are not worse at night and symptoms are not temporarily improved by movement. TABLE 23–2 Characteristics of Restless Legs Syndrome Mimics EMG = electromyogram; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; RLS = restless legs syndrome. Hypnic jerks are usually single, whole body jerks that occur at sleep onset. They are not associated with abnormal sensations. Neuropathy may present as pain and/or burning in the legs or feet but is usually associated with an abnormal neurologic examination and is not associated with an urge to move. Neuropathic pain is usually not improved with movement or rubbing. The pain may be worse at night but is usually present during the day. RLS and neuropathy can exist together. Positional discomfort is associated with a need to move in bed to relieve pressure that compresses nerves, limits blood flow, or stretches tissue. The sensations may be painful but are improved with change in position rather than with movement. Neuroleptic akathisia is characterized by involuntary movement of the face or extremities (such as body rocking, marching in place, or movement of the extremities) and is NOT worse during the night or at rest. There is invariably a history of use of neuroleptics (phenothiazines) and other dopamine blockers (metoclopramide). The movements are associated with inner restlessness but not abnormal sensations. The painful legs–moving toes (PLMT) syndrome13,16 is characterized by pain in the lower limbs with spontaneous movements of the toes or feet. Variants of PLMT that are painless or involve the arms and hands also exist. The pain is most often burning in nature and commonly precedes spontaneous movements consisting of flexion/extension, abduction/adduction, fanning, or clawing of the toes, fingers, foot, or hand. Causes of PLMT include nerve root lesions, herpes zoster, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), neuroleptics, chemotherapeutic agents, peripheral trauma, and polyneuropathy from alcoholism. Nocturnal leg cramps are associated with localized severe pain and tightness in a muscle. These are improved with stretching but not just movement. Claudication may be associated with pain even at rest, if severe, but is usually NOT improved with movement. Usually, claudication symptoms are worse with exertion. Common causes of RLS are listed in Box 23–5. RLS is often divided into primary RLS (independent of other disorders) and secondary RLS (due to an identifiable cause such as a medical disorder, condition, or medication). The cause of primary RLS is not known. There may be an abnormality in iron transport into the central nervous system or utilization of iron as it relates to dopaminergic neurons. Causes of secondary RLS include renal failure, pregnancy, iron deficiency (with or without anemia), and certain medications. Medications associated with RLS include tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin reuptake inhibitors, dopamine blockers (phenothiazines, haloperidol, metoclopramide), sedating antihistamines (diphenhydramine), and antinausea medications (prochlorperazine). RLS associated with renal failure is not helped by dialysis but is cured by renal transplantation. The RLS of pregnancy commonly vanishes or improves with delivery. It is prudent to check a serum iron, total iron-binding capacity (TIBC), and ferritin in patients with RLS. It is recommended that RLS patients have a ferritin above 45 to 50 µg/mL.17 The RLS of iron deficiency may improve with iron supplementation. If the onset of RLS can be linked to the start of a given medication, a switch to an alternate medication can be tried. For example, bupropion is an antidepressant that does not worsen RLS.18 In one study, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) medications and venlafaxine were more likely to be associated with PLMS than either a control group or a group taking bupropion.19 Thus, bupropion might be less likely to cause or worsen RLS. In 50% to 60% of cases of RLS, a family history of RLS can be found.13,20 Twin studies show a high concordance rate. Most pedigrees suggest an autosomal dominant pattern; however, a recessive pattern with a carrier phenotype is also possible. Familial RLS has onset of symptoms at a younger age and is more slowly progressive. The genetics of RLS, as in many medical conditions, is complex21–30 (Table 23–3). Linkage studies have found RLS loci but no related disease-causing sequence variants have been found. More recent genome-wide association studies have identified three genomic regions MEIS1, BTBD9, and MAP2K5/LBXCOR1. In one study, the presence of a genetic risk for the presence of PLMS was found whether or not RLS symptoms were present.29 TABLE 23–3 Genetic Linkages and Associations in Restless Legs Syndrome Adapted from Hening WA, Buchfuhrer MJ, Lee HB: Clinical Management of Restless Legs Syndrome. West Islip, NY: Professional Communications, 2008, pp. 56–57. The pathophysiology of RLS is not well understood.21,31–34 Central nervous system iron homeostatic dysregulation is thought to be the basic mechanism. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) ferritin is lower (and transferrin is higher) in RLS patients. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) using special sequencing techniques can provide measures of iron concentration in specific brain regions. Using this technique, imaging showed reduced iron stores in the striatum and red nucleus.34 The dopaminergic system is also believed to be involved in RLS. Iron is a cofactor for the enzyme tyrosine-hydroxylase, which is a rate-limiting step in the formation of dopamine. RLS patients show a greater circadian variation in dopamine metabolites than controls. This would be consistent with the circadian component of RLS. The current theory of the causation of RLS is sometimes called the iron-dopamine hypothesis. A number of studies have attempted to define the prevalence of RLS. The results vary considerably due to the use of different RLS diagnostic criteria and different methods (survey vs. direct patient interview).1,2,13,35,36 Approximately 5% to 10% of adults in Northern European countries report RLS symptoms. RLS is approximately 1.5 to 2 times more common in women than in men. However, much of the difference in RLS prevalence between men and women is likely due to the association of RLS with pregnancy. The Restless Legs Epidemiology, Symptoms, and Treatment Study (REST)35 was a large questionnaire evaluation of 23,052 primary care patients. The study found that the overall prevalence of weekly RLS symptoms was 9.6% and that the prevalence increased with age (Fig. 23–2). A large international study of a general population (REST general population study) found that 5% of the respondents experience RLS symptoms weekly and 2.7% reported symptoms at least twice weekly and that the symptoms had a negative impact on their life.36 RLS can begin at any age and the clinical course is variable. Two patterns are commonly seen (see Box 23–6).13 An early onset (age < 50 yr) characterized by insidious onset, less severity, and higher familial association. A late onset RLS (age > 50 yr) is characterized by a more abrupt onset and more severe manifestations. Late-onset RLS patients also tend to have lower ferritin levels compared with early-onset RLS patients. The two most common complaints that cause RLS patients to seek medical attention are the uncomfortable leg sensations and the disturbance of sleep. Beyond the significant discomfort caused by RLS symptoms, the disorder can cause difficulty with sleep initiation and maintenance A recent large questionnaire study of 23,052 primary care patients identified a group of “RLS sufferers” (N = 551) with RLS symptoms twice or more weekly and a negative impact from RLS symptoms.35 In this group, 43.4% complained of sleep-related symptoms but only 6% complained of daytime sleepiness. On nights that RLS symptoms were present, 69% complained of taking over 30 minutes to fall asleep and 60% complained of three or more awakenings per night (Table 23–4). Daytime sleepiness is a less common symptom than insomnia but can occur. In a general population study, the prevalence of RLS of any frequency was 7.2%, weekly RLS symptoms was 5%, and twice-weekly symptoms with distressing symptoms was 2.7%.36 Of the group with RLS twice weekly or more, 81% had reported symptoms to primary physicians but only 6.2% were given a diagnosis of RLS. TABLE 23–4 Manifestation of Restless Legs Syndrome in Restless Legs Syndrome “Sufferers” (N = 551) Data from Hening W, Walters AS, Allen RP, et al: Impact, diagnosis and management of restless legs syndrome in a primary care population: the REST (RLS Epidemiology, Symptoms, and Treatment) Primary Care Study. Sleep Med 2004;5:237–246. The etiology of sleep disturbance from RLS includes a delay in sleep onset due to RLS symptoms. If the patient awakens, the return to sleep may also be delayed by RLS symptoms. Because the majority of RLS patients have PLMS, it might be assumed that arousals associated with PLMS contribute to sleep disturbance. However, the PLMSI (number of PLMs/hr of sleep) is not highly correlated with any measure of sleep disturbance in most studies of RLS patients.12 In a study of unmedicated RLS patients, Hornyak and coworkers37 found that the IRLSSG rating scale (IRLS) score38,39 (RLS symptoms severity) correlated with the PLMS arousal index but not the PLMSI. However, even the relationship between the IRLSSG rating scale (IRLS) and the PLMS arousal index was very weak (r = 0.22, P = .03). The diagnostic evaluation (Box 23–7) should include a history to elicit the essential and associated features of RLS. A detailed medication history including over-the-counter (OTC) medications (sedating antihistamines) is very important. The IRLSSG developed a rating scale for RLS symptoms called the IRLSSG rating scale (IRLS).38,39 A slight revision of the validated scale38 was published as an appendix to an editorial.39 The IRLS is useful to quantify RLS symptom severity and the effects of treatment (Box 23–8). The scale is used in research studies but also has clinical utility in following patients on treatment.

The Restless Leg Syndrome, Periodic Limb Movements in Sleep, and the Periodic Limb Movement Disorder

RLS

PLMS

PLMD

Diagnosis

History

PSG

PSG + History

Prevalence

Common

Very common

Rare

Associated findings

Relationship with other leg movement conditions

A diagnosis of RLS excludes a diagnosis of PLMD

A PSG finding not a disorder

Not diagnosed if RLS is present

Restless Legs Syndrome

The Essential RLS Diagnostic Criteria6,13

Supportive Clinical Features

Differential Diagnosis of RLS/PLMS

URGE TO MOVE

ABNORMAL SENSATIONS

WORSE IN THE EVENING/NIGHT

IMPROVED BY MOVEMENT

NEUROLOGIC STUDIES

NEUROLEPTIC USE

RLS

Yes

Usually

Always

Temporary improvement

Neurologic examination usually normal, EMG often normal

No

Hypnic jerk

No

No

Sleep onset

Single whole body jerk

Normal

No

Neuropathy

No

Yes, can be painful

Sometimes

No

Decreased sensation, abnormal EMG/nerve conduction

No

Positional discomfort

Yes

Usually

Usually

Change in position not movement

Variable

No

Neuroleptic akathisia

Inner restlessness

No

Not usually

Not usually

Variable

YES

Leg cramps

No

Pain localized to muscle

Sometimes

Stretching not movement

Normal

No

Claudication

No

Pain

Not usually

Walking may worsen

Decreased pulses

No

Painful legs, moving toes syndrome

No

Pain, burning

Not usually

No

Abnormal EMG, MRI may show lumbosacral nerve compression

No

Causes of RLS

Familial Patterns and Genetics

LINKAGES

AUTHOR

POPULATION

CHROMOSOME

MODEL

RLS-1—Desautels, 200122

French Canadian

12q

Recessive

RLS-2—Bonati, 200323

Italian

14q

Dominant

RLS-3—Chen, 200424

United States

9p

Dominant

RLS-4—Levchenko, 2006,25 200926

French Canadian

20p

Dominant

RLS-5—Pichler, 200627

Italian

2q

Dominant

ASSOCIATIONS

AUTHOR

POPULATION

CHROMOSOME

GENE

Winkelmann, 200728

French Canadian/European

2p

MEIS1, exon 9

6p

BTBD9, intron 5

15q

MAP2K5, LBXCOR1

Stefannson, 200729

Icelandic/US

6p

BTBD9

Winklemann, 200730

European

12q

BTBDR, intron 5

Pathophysiology of RLS

Prevalence of RLS

Onset and Clinical Course of RLS

Sleep Disturbance Associated with RLS

At least one sleep-related symptom

43.4%

Consulted MD about symptoms

64.8%

Given RLS diagnosis

24.9%

ON NIGHTs when RLS SYMPTOMS PRESENT

>30 min to fall asleep

68.6%

≥3 awakenings

60.1%

Medical Evaluation in RLS

The Restless Leg Syndrome, Periodic Limb Movements in Sleep, and the Periodic Limb Movement Disorder