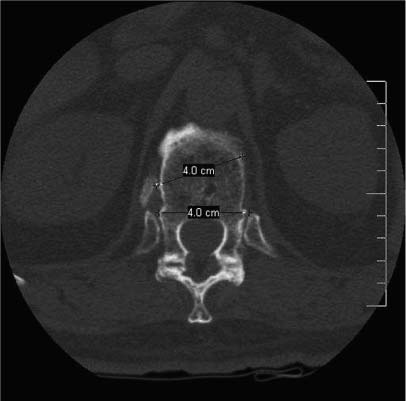

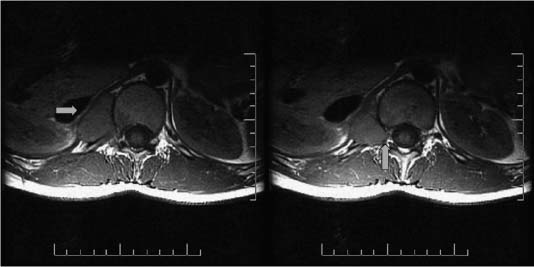

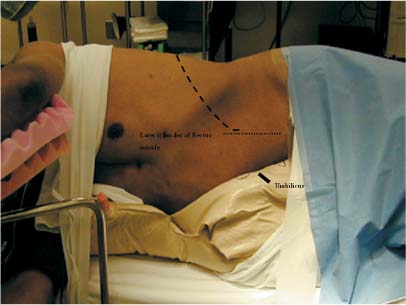

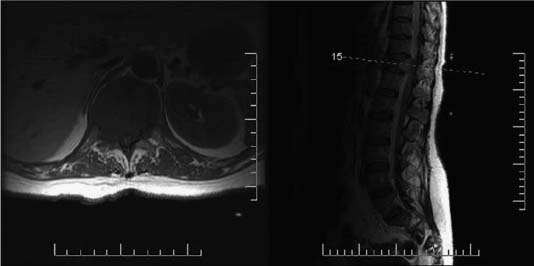

30 Surgeons need to gain access to the ventral spine at the thoracolumbar junction to treat tuberculous lesions,1,2 pyogenic osteomyelitis,3,4 kyphotic deformities,5 neoplasms (primary and metastatic),6,7 and burst fractures.8–11 The type of ventral approaches used for the different levels is covered in detail in the relevant chapter. This chapter discusses the thoracotomy and thoracoabdominal transdiaphragmatic approach. Preoperative preparations consist of imaging the pathology and assessing the patient. Different imaging modalities can be combined to provide complementary information about the anatomy and pathology in question. The role of plain x-rays cannot be overlooked. In cases with severe deformity, standing x-rays of the entire spine allow a more accurate assessment of the coronal and sagittal balance of the patient. A construct has a higher rate of failure or adjacent disruption if the balance of the spine in either plane is not respected. A 3-foot x-ray allows the surgeon to consider the entire spine as opposed to only the diseased segment (Fig. 30-1). Computed tomography (CT) scans provide valuable information especially with respect to the quality and size of the bony anatomy. They are used not only during the decompression but also at the time of reconstruction for the fusion and fixation (Fig. 30-2). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) sensitivity for the soft tissues enhances our understanding of the level and extent of compression and its relation to the neural elements. FIGURE 30-1 A lateral spine x-ray can provide information regarding the sagittal balance. In this case, the scout view taken from the computed tomography (CT) scan can be misleading because the patient is lying down. A standing 3-foot x-ray would demonstrate more accurately the overall sagittal and coronal balance of the entire spine. The dotted line indicates the anterior aspect of the spinal canal, taking into consideration the accentuated convex nature of the posterior aspect of the vertebral bodies at the thoracic level. FIGURE 30-2 CT scan with axial image demonstrating preoperative planning of screw fixation. The optimal screw trajectory and the length of the screw can be measured with a high degree of accuracy. Greater appreciation of the osteophytes can be obtained compared with standard x-rays images. Certain navigational systems can merge images from the MRI and CT scan modalities. This assists the surgeon to maximize the extent of decompression and the subsequent reconstruction of the spinal defect. The indications for spinal angiograms are limited in our institution for embolization. Preoperative embolization helps to minimize the intraoperative blood loss during tumor resection. Preoperative identification of the artery of Adamkiewicz does not change our surgical planning and therefore is not necessary. In addition to the neurologic assessment, the patient assessment focuses on the pulmonary and cardiovascular systems. Pulmonary function can be ascertained by measuring the forced vital capacity and maximum breathing capacity. Cardiac status can be studied with functional inquiry and basic investigations such as electrocardiogram and cardiac enzymes. The functional inquiry determines the need for further study. At our institution all patients are seen by the anesthesia service before the operation. The patient’s pulmonary and cardiovascular status is reviewed in preparation for a general anesthetic and the possible intraoperative collapse of a lung. Optimization of medical management prior to surgery is ensured. Patients with nonneoplastic diseases are asked to donate blood for autologous blood donations 30 days prior to surgery. Storage of two units of the patient’s blood is encouraged in most eligible candidates. The site, level, and extent of pathology are all considered when deciding on a right- or left-side approach. Some tumors involve the entire vertebral body, whereas others may be eccentric (Fig. 30-3). The exposure must allow the appropriate amount of resection to be achieved. The level is equally important when approaching the thoracolumbar spine. In a right-sided approach, the liver can limit the amount of retraction allowed (Fig. 30-4). The great vessels also present an obstacle, but for the most part arteries are easier to repair than veins. The surgeon must be able to control the bleeding and repair the vessel should the need arise. Placing the patient in the lateral decubitus position offers certain benefits to the surgeon. The first is an orthogonal orientation of the spine. This point becomes important when dealing with a tumor-invaded spine with loss of some or all of the normal anatomic landmarks. The interpretation of intraoperative x-ray or fluoroscopic images can be simpler when a true lateral or anteroposterior view is taken. Gaining access can sometimes be difficult because of the body habitus of the patient. In this case, placing the level of interest over the break point of the table can allow the surgeon to laterally bend the spine if necessary. Securing the patient to the operating table by means of tape or straps is highly recommended because the operating table may be moved to optimize the visualization. We routinely perform a test tilt of the table once the patient has been secured, but prior to draping. This not only confirms the patient is secure but also gives the anesthetist a chance to see the anticipated intraoperative movement of the patient. Padding is placed over the elbows and knees to minimize the likelihood of developing pressure palsies. An axillary roll is used to relieve the axilla of any pressure and thus minimize potential damage to the brachial plexus. To further reduce the chance of nerve palsies, intraoperative monitoring has been extended to include the ulnar and peroneal nerves in most of our cases. Flexion of the hip allows the psoas muscle to relax. This maneuver facilitates the retraction of the muscle on the up side of the patient. The skin incision is centered on the selected rib. The selection of the optimal rib to be resected is based on the levels needed for exposure. For example, if the 10th thoracic vertebra is going to involved in the surgical exposure, the 8th rib may prove to be the best level of approach. Choosing higher ribs is necessary because of the diagonal orientation of the ribs with respect to the spine. For the lower thoracic spine, one rib above may be sufficient. An intraoperative x-ray, prior to draping, with a radiopaque marker, often helps in selecting the best rib for resection. This x-ray also confirms the optimal patient position on the table and facilitates interpretation of subsequent x-rays. FIGURE 30-3 Two contiguous axial T1 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans illustrating a hepatocellular carcinoma extending into the right neuralforamina arrows. This lesion required a right-sided transdiaphragmatic approach for its complete resection. FIGURE 30-4 Axial T1 MRI on the left and corresponding sagittal T2 MRI on the right showing a T11 metastatic breast carcinoma. The entire T11 vertebral body invasion is well demonstrated as is the canal compromise at the involved level. The liver, best seen on the axial image, presents a significant obstacle for the right-sided approach. FIGURE 30-5 The patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position with the left side up. The anterior view demonstrates the level of the skin incision in relation to the lateral border of the rectus abdominis muscle. FIGURE 30-6 Same patient as in Figure 30-5. The posterior view demonstrates the extent of the skin incision in relation to the paraspinal musculature. The patient is secured to the operating table and the level of the skin incision is directly over the break point. This allows lateral bending of the patient, providing easier access. Following decompression and specifically prior to fusion and instrumentation, the operating table must be back in its flat position. The incision is made directly over the selected rib, extending posteriorly from the lateral border of the paraspinal musculature and anteriorly to the lateral aspect of the rectus abdominis muscle (Figs. 30-5 and 30-6). The incision takes a more vertical direction once it is beyond the costal cartilage to facilitate the retraction of the peritoneum and its contents. The skin incision for a thoracotomy is less extensive and may be stopped anteriorly at the midclavicular line. Rotation of the scapula by adjusting the ipsilateral arm can, in some cases, provide adequate access for the upper thoracotomy approach. Several large muscles are incised for the transthoracic approach, and particular attention is required for their dissection and repair. The latissimus dorsi muscle is best separated by cutting the muscle fibers at a right angle from their long axis and as inferiorly as possible to keep as much of the muscle as possible innervated. This technique takes into consideration the innervation from the thoracodorsal nerve coming from the brachial plexus and facilitates repair at the end of the procedure. The serratus anterior muscle can also be separated in the same fashion to help with repair. The approach can now be divided into the transthoracic and the retroperitoneal component. A helpful tip for reapproximating tissue planes at the end of the procedure is to cut the anterior cartilaginous tip in half. This tip indicates the junction between the transthoracic and retroperitoneal components of the approach. The transthoracic approach requires the surgeon to cut down onto the rib selected, using a monopolar cautery (Figs. 30-7 and 30-8). To free the rib of the external and internal intercostal muscles, a sharp instrument is used, taking care not to injure the underlying lung. By staying in a subperiosteal plane, stripping the muscles from the rib can be achieved with minimal blood loss. Dissection of the muscular wall lateral to the rectus abdominis muscle requires the surgeon to cut through the external and internal oblique abdominal muscles, followed by the transverse abdominal muscle, prior to entering the peritoneal space. Leaving the peritoneal cavity intact, lateral blunt dissection allows access to the retroperitoneal space. Adequate visualization of the psoas muscle and the anterior aspect of the spine can be achieved. When access to the upper lumbar vertebrae is needed, the psoas muscle must be retracted laterally. The need to visualize the ureter is based on minimizing trauma either directly or with retraction. Identification of the ureter anterior to the psoas muscle can sometimes be challenging. Gentle squeezing initiates spontaneous contractions, which helps differentiate this structure from vessels or nerves.

Thoracotomy and Thoracoabdominal Transdiaphragmatic Approaches to the Thoracic and Lumbar Spine

Operative Technique

Operative Technique

Preoperative Planning

Patient Positioning

Surgical Approach

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree