Unenhanced CT show signs of acute stroke of the left MCA territory. (a) Hyperdense left MCA sign, in which high attenuation thrombus is seen extending from the left internal carotid artery terminus through the distal left M1 segment. (b) Parenchymal early changes of ischemic stroke are seen, such as effaced sulci and cortical swelling on the left cerebral hemisphere.

Because the last time he was seen well was more than 5 hours earlier, he was not treated with thrombolytic therapy with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA). Further etiological investigation with a neck vascular ultrasound showed an occlusion of the left internal carotid artery (ICA) due to a large atheromatous plaque. Transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasound confirmed the absence of flow in the left MCA compatible with occlusion of this vessel. The patient received conservative treatment aimed at preventing medical complications, correction of risk factors, and secondary prevention. Three weeks after admission he was discharged dependent to a rehabilitation clinic, scoring 5 on the modified Rankin scale (mRS).

Discussion

The first episode presented by this patient had characteristic symptoms of a TIA. Speech disorder and unilateral weakness are typical symptoms of TIA. Many stroke awareness campaigns include these symptoms as warning signs of stroke and educate the public to seek emergency assistance. Just because symptoms abate, it does not mean that the situation has become less urgent. Indeed, urgent evaluation of this patient at the time he had the initial TIA could have led to the institution of therapy to modify the natural history of the disease. Conversely, if the institution of preventive therapy was not enough to prevent stroke that occurred during hospitalization, the patient could have been treated with rtPA and might have suffered a less devastating consequence of his stroke.

Unfortunately, this is not a rare occurrence. About 15–20% of patients who suffered a stroke had previously experienced a TIA, 17% had a TIA on the same day as the stroke, 9% on the day before, and 43% within the previous 7 days [3]. Many of these patients had not sought medical assistance.

Although a TIA does not cause immediate sequelae, affected individuals have a high risk for future ischemic events. A recent systematic review of stroke risk following TIAs showed the pooled risk of recurrent stroke to be 5.2% at 7 days, 6.7% at 90 days, and 11.3% at >90 days [4].

Timely and appropriate treatment of TIAs can drastically reduce stroke risk. This is supported by at least two leading sources of evidence: (1) The EXPRESS (Early Use of Existing Preventive Strategies for Stroke) study examined the effect of immediate care compared with delayed care among 1278 TIA and stroke patients, and found that early care resulted in an 80% reduction in the 90-day risk of secondary stroke [5]. Management included assessment and referral for carotid endarterectomy if appropriate, warfarin for patients in atrial fibrillation, and immediate initiation or adjustment of antiplatelets, statins, and antihypertensive agents if the systolic blood pressure was >130 mmHg. (2) A French study showed the feasibility of assessing and treating TIA patients as soon as possible after the event in a TIA clinic providing 24-hour access (SOS-TIA). At the end of 2 years, the 90-day stroke risk in more than 1000 TIA patients was 1.24%, lower than could have been expected according to the potential risk of recurrence if these patients were not treated on an emergency basis [6].

It is of the utmost importance to treat these patients as soon as possible following the TIA. The risk of stroke is particularly high immediately after the TIA. In a prospective population-based incidence study of TIA and stroke (OXVASC), the risks of stroke at 6, 12, and 24 hours were 1.2%, 2.1%, and 5.1%, respectively [7]. Therefore, these transient events warrant complete evaluation and management in an acute setting. This setting should be defined according to local resources, and may be at emergency rooms, stroke units or TIA clinics. Most guidelines now recommend that patients with TIAs should be assessed within 24 hours of their event, but undoubtedly the feasibility of this depends on patients’ behavior.

Tip

Increased awareness of symptoms and signs of TIA and stroke is needed among the population. Even if symptoms subside patients should be urgently evaluated. TIAs warrant complete evaluation and management in an acute setting, because the risk of stroke is particularly high in the first days following these transient events.

Case 2. TIA – can I go home while awaiting etiological investigation?

Case description

A 67-year-old woman went to the ED complaining of difficulties in moving her right limbs. Symptoms began suddenly when she was setting the table for lunch. She sat up, and the symptoms abated after 40 minutes. She did not have changes in her speech, sensation, or limb coordination. She had never had similar episodes or other diseases of the nervous system. Past medical history was remarkable for hypertension, dyslipidemia, and cigarette smoking. She was receiving atorvastatin 20 mg daily, and atenolol 50 mg daily. At the ED, blood pressure was 163/85 mmHg, and heart rate was 54 beats per minute and regular. She had a left cervical bruit. Otherwise, general physical and neurologic examinations were normal. An emergent brain CT scan was normal. Blood analyses were normal. Except for sinus bradycardia, the electrocardiogram was normal.

This index event occurred around Christmas, and her wishes were to go home rather than being hospitalized. However, she was told of the potential risks of stroke, and finally agreed to be hospitalized. The patient was immediately started on aspirin 250 mg daily and 80 mg of atorvastatin daily. Atenolol was replaced by an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI).

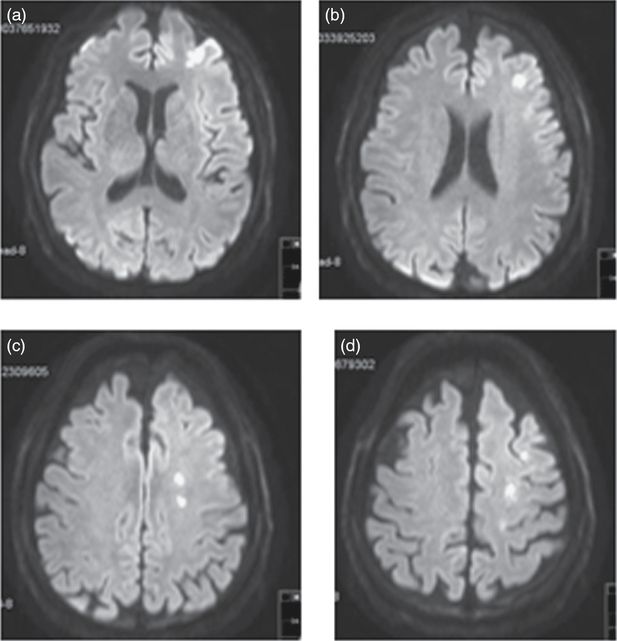

A carotid Doppler ultrasound displayed a high-grade (90%) atherosclerotic left internal carotid artery stenosis, and a moderate (50%) atherosclerotic right carotid stenosis. TCD ultrasound demonstrated diminished flow velocities on the left MCA, and collateral blood flow through the circle of Willis secondary to extracranial carotid stenosis. Diffusion-weighted MRI showed several small bright signals compatible with acute ischemia at the border zone between the MCA and anterior cerebral artery (ACA) vascular territories (Figure 3.2).

Abnormal MRI diffusion-weighted imaging showing multiple hyperintense signals in successive brain slices associated with acute ischemia at the border zones between left MCA and ACA vascular territories.

A left carotid endarterectomy (CEA) was performed the same week, and the patient was discharged home without neurologic deficits. She was encouraged to quit smoking, optimize risk factor control, increase her physical activity, and continue on antiplatelet drugs, high dose statins, and a combination of a diuretic and ACEI.

Discussion

Given the presence of vascular risk factors and clinical presentation, her transient symptoms were easily attributed to TIA. There were no other neurologic conditions suspected as an alternative diagnosis. Furthermore, the cervical bruit raised suspicion of carotid artery stenosis as the possible cause of the event. All these characteristics were taken into consideration to estimate the immediate risk of stroke, and to decide whether she should be admitted to hospital immediately or discharged to complete the investigation and treatment in an outpatient clinic.

Several clinical risk prediction scores have been developed to identify patients at high risk of stroke and assist clinicians to decide how urgently those patients need to be evaluated. The ABCD2 score has achieved particular relevance and has been adopted by many stroke services, emergency departments, and primary care physicians to guide triaging of patients with TIAs. The ABCD2 score includes: age (>60 years, 1 point); blood pressure elevation on first assessment after TIA (systolic >140 mmHg or diastolic >90 mmHg, 1 point); clinical presentation (unilateral weakness (2 points), speech disturbance (1 point, if there is not motor weakness)); duration of symptoms (≥60 minutes, 2 points; 10–60 minutes, 1 point) and diabetes mellitus (1 point) as clinical variables [8].

The ABCD2 score classifies TIA patients at low, moderate, or high risk using cutoff points of <4, 4–5, and >5. Some clinical guidelines advocate admission to hospital and early assessment/treatment for patients with an ABCD2 score of ≥3, others recommend a specialist assessment and investigation within 24 hours of symptoms for patients with an ABCD2 score of ≥4 and within 1 week for those patients with an ABCD2 score of <4 [9]. A recent systematic review evaluated data on the performance of the ABCD2 score to predict stroke recurrence among patients at high risk (score ≥4) and low risk (score of <4) of stroke [4]. The corresponding pooled risks of stroke for patients with ABCD2 score of ≥4 and <4 at 7 days were 7.5% (95% CI 4.7–11.7) and 2.4 (95% CI 1.3–4.2), respectively.

Our patient had an ABCD2 score of 5. Based on the score, we had enough data to recommend her to be admitted to hospital and start secondary prevention without delay. But we additionally suspected the patient might have left ICA stenosis which would further increase the risk of stroke [10]. Accordingly, we strongly recommended her to be hospitalized despite her wish not to spend Christmas in hospital. Doppler ultrasonography confirmed she had a severe symptomatic left ICA stenosis and thus, she was referred for urgent endarterectomy, the benefit of which is highest when performed within 2 weeks of the index ischemic event [11].

Thus, the addition of information obtained from etiological investigation and brain imaging may further improve the prediction of stroke among TIA patients. Although this was not the case in our patient because she already had a very high ABCD2 score, an important pitfall of using the ABCD2 score alone may be not identifying other established markers of high stroke risk, such as carotid stenosis or atrial fibrillation [12–16]. Adding carotid artery stenosis to the ABCD2 score improves stroke risk prediction [17,18]. Refined versions of this score were proposed, including data based on imaging and vascular assessment, deriving a new score (ABCD3-I) [17].

Approximately 10–15% of patients with an ABCD2 score of <4 have carotid artery stenosis of >50% or even >70% and should therefore be referred for endarterectomy [12,15,16]. In a French cohort, patients with TIAs and ABCD2 scores of <4 had similar 90-day risk of recurrent stroke (3.9%) as those with a score of ≥4 (3.4%) in the presence of internal carotid or intracranial artery stenosis of ≥50% estimated by North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) criteria, or major cardiac source of embolism [15].

Another interesting finding in our patient concerns the results of brain MRI, because it displayed several acute ischemic lesions. Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) shows a definite acute ischemic lesion in about one-third of TIA patients, being negative in two-thirds [19]. The presence of an ischemic lesion on DWI MRI has been associated with an increased risk of stroke in TIA patients, independently of the ABCD2 score, and these findings have been incorporated in the proposed ABCD3-I score (I – lesion in the brain) [4,17].

Taking all these data into consideration, we can summarize that our patient had several characteristics that placed her at high risk of a stroke: high ABCD2 score, severe degree of carotid artery stenosis, and an acute ischemic lesions on DWI MRI. Urgent evaluation was thus essential for the good outcome she had.

Tip

The ABCD2 score is a useful tool to stratify the risk of stroke among patients with TIAs. If the ABCD2 score is ≥4, patients need urgent evaluation and treatment. But a low ABCD2 score cannot exclude other conditions that potentially increase stroke risk. Brain imaging and carotid vascular studies should be urgently performed aiming to further individualize the stroke risk and appropriate treatment of these patients.

Case 3. Repeated TIAs – does it change the patient’s management?

Case description

A 58-year-old left-handed physician with a history of ischemic heart disease and heavy cigarette smoking was admitted because of sudden onset of slurred speech and weakness of his left limbs. Symptoms started upon awakening, and completely resolved after 2–3 minutes. He had had similar symptoms one month earlier; symptoms consisted of decreased strength on the left side of the body which lasted a minute or two. He was noncompliant with the medications proposed for control of ischemic heart disease, and only took aspirin on an irregular basis. On admission, blood pressure was 120/65 mmHg, and heart rate was 67 per minute and regular. General physical and neurologic examinations were normal. While waiting for the CT scan on the ED, he had another transient event consisting of left limb paresis. This episode was observed by the ED physician, confirming the weakness of both left limbs that transiently became hypotonic. The patient also had left facial paresis and dysarthria. During these episodes he never mentioned sensory or visual symptoms, lack of coordination, or clonic movements.

CT scan was normal. Blood analysis showed a high cholesterol of 223 mg/dL and a low-density lipoprotein (LDL) of 164 mg/dL. ECG was normal. Due to the repeated occurrence of the TIAs a carotid ultrasonography was performed at the ED, which showed small regular atheromatous plaques in both carotid bifurcations without stenosis. The patient was admitted to the stroke unit to be monitored and complete etiological investigation. Aspirin 250 mg daily and atorvastatin 80 mg daily were started.

TCD revealed a marked increase in flow velocities at the origin of the right MCA (systolic velocity 290 cm/s; diastolic velocity 200 cm/s). Brain MRI was normal. Cerebral angiography showed a focal stenosis of the proximal segment of the M1 portion of the right MCA (Figure 3.3). No other abnormalities were found in the other cerebral arteries. Testing for orthostatic hypotension was negative.

Cerebral angiography shows a severe right MCA (M1) stenosis (arrow).

During the first day of hospital stay, the patient had another transient event while lying down. Blood pressure was 137/78 mmHg and the episode resolved after one minute. At that time, clopidogrel 75 mg daily was added to aspirin. The patient was discharged 3 days after. No further TIAs were reported. The patient was seen at the TIA clinic one month later and he did not report further events. A TCD was repeated, and was similar to that performed during hospital admission. The patient did not completely quit smoking, but was otherwise compliant with his medications.

Discussion

This patient presented with repeated stereotyped negative symptoms, suggestive of a TIA. Once the diagnosis of TIA is established, one of the first steps is to determine which vascular territory is affected, as this may guide further etiological investigation and treatment. However, this may be difficult because of the paucity of neurologic abnormalities at the time of evaluation, and the need to rely on the patient’s description. Moreover, similar symptoms can be produced by ischemia in different vascular territories. Such an example is the clinical presentation of our patient, which was characterized by unilateral motor deficits and slurred speech. In general, isolated unilateral symptoms are taken as suggestive evidence for anterior circulation ischemia, but ischemia involving the pons, the cerebral peduncles, or the medullary pyramids produce virtually indistinguishable symptoms. In our patient, the absence of cortical symptoms suggested a subcortical or brainstem location. Sometimes, MRI can help determine which is the vascular territory affected, but this was not the case with our patient as his MRI was normal.

The recurrent symptoms at the time he went to hospital, consisting of a burst of stereotyped TIAs with unilateral motor deficits involving at least two of three body parts (face, arm, or leg) without cortical symptoms, were evocative of the “capsular warning syndrome” [20] or “pontine warning syndrome” [21]. These syndromes have been closely linked to single penetrating artery disease, and have been associated with a high early risk of lacunar infarction. The pathophysiology is complex, and may involve hemodynamic mechanisms in penetrating arterial territories. Contrary to what is described in those warning syndromes, our patient reported a similar event about one month earlier. This argued against a small vessel etiology, and ultimately, the demonstration of a right MCA stenosis established the cause of his recurrent TIAs.

Our patient had an ABCD2 score of 2, which portends a low recurrence risk, but this case highlights that we would have incurred a pitfall if our decision was based exclusively on this score. If we had decided against admitting him to hospital because of the low ABCD2 score and normal ultrasound study of the extracranial vessels, we could have referred him for a less urgent evaluation, missing an important etiology and underestimating the true stroke risk.

The presence of two or more TIA symptoms within 7 days has been associated with a higher short-term risk of stroke. Indeed, the refined ABCD3 score (the third “D” meaning dual TIA) is more accurate in identifying patients at high risk compared with the ABCD2 score [17]. Moreover, recent studies have shown that intracranial arterial stenosis is associated with recurrent stroke after TIA [22].

Taking all these data into consideration – the clinical presentation, recurrence of TIAs, and the presence of intracranial stenosis – we concluded that the patient had a high stroke risk. Once he had a subsequent TIA while on aspirin, we added clopidogrel. Dual antiplatelet therapy is not a standard recommendation for secondary stroke prevention, but among selective high-risk patients, where conventional maximal therapy fails, it might be reasonable to prescribe dual antiplatelet therapy. The Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients With Acute Non-disabling Cerebrovascular Events (CHANCE) trial, demonstrated a benefit of combination therapy (aspirin plus clopidogrel vs. aspirin alone) for patients with an acute minor ischemic stroke or TIA within 24 hours of their event [23]. This trial only enrolled Chinese patients, thus we should be prudent when generalizing its results.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree