20 Transplanum, Transtuberculum Approach

Gurston G. Nyquist, Vijay K. Anand, and Theodore H. Schwartz

Introduction

Introduction

Extended endoscopic transsphenoidal approaches have been adapted to address a variety of lesions beyond intrasellar pathologies (Fig. 20.1).1–6 The suprasellar cistern is a region located above the diaphragma sellae, and midline lesions of this area are especially amenable to an endoscopic transsphenoidal, transplanum, transtuberculum approach. The extended application of the transsphenoidal approach to manage suprasellar pathologies represents the next step in the development of an endoscopic skull base practice after the surgeon has mastered the transsphenoidal, transsellar approach.

It is imperative to clearly define the surgical objectives preoperatively, and this largely depends on the biologic characteristics of the lesion. Rathke cleft cysts are benign congenital lesions derived from remnants of Rathke’s pouch. The local mass effect of these lesions can produce headaches, pituitary dysfunction from compression on the pituitary gland or stalk, and visual impairment secondary to optic chiasm compression. Although complete excision of the cyst is possible, the surgical goal is usually decompression of the cyst for symptomatic relief and to obtain a biopsy of the cyst wall.7

Craniopharyngioma is a slow-growing, epithelial-squamous, calcified cystic tumor arising from remnants of the craniopharyngeal duct and/or Rathke cleft (Fig. 20.1B). Craniopharyngiomas are dysontogenic tumors with benign histology and malignant behavior, as they have a tendency to invade surrounding structures. Craniopharyngioma usually presents as a single large cyst or multiple cysts filled with a turbid, proteinaceous material of brownish-yellow color owing to the high content of floating cholesterol crystals. It most frequently arises in the pituitary stalk and projects into the hypothalamus and third ventricle.

Management options for craniopharyngioma include gross total tumor resection or cyst decompression for symptomatic relief followed by radiotherapy. Inflammatory reactions make the tumor adherent to critical neurovascular structures, and attempts at complete resection may significantly damage the hypothalamic-pituitary axis. Serious psychosocial deficits are also possible with hypothalamic injury, and preservation of hypothalamic function is imperative. Goals for surgery include gross tumor resection when possible, preservation of the patient’s ability to maintain independent social functioning, prevention of symptomatic recurrence, and survival.

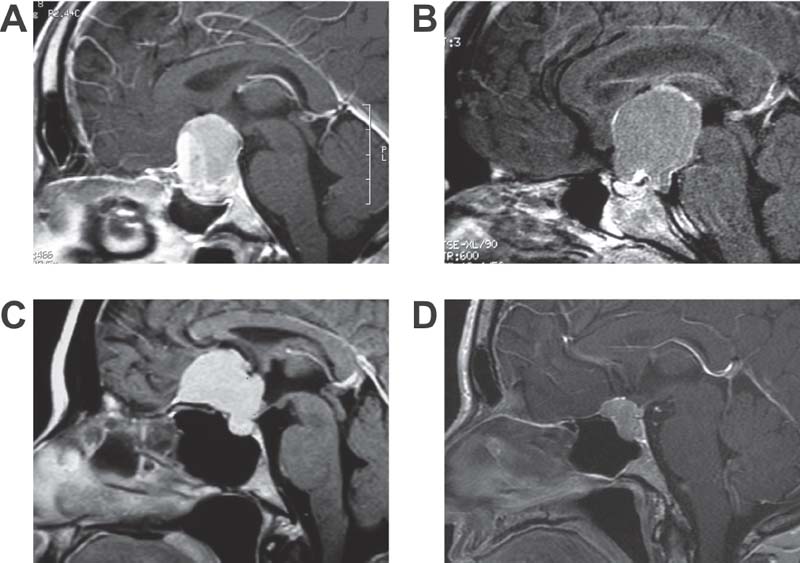

Pituitary macroadenomas often extend into the suprasellar cistern; however, these lesions can often be removed with a wide opening of the bony sella (Fig. 20.1A). Thorough, systematic removal of sellar portions of the adenoma facilitates descent of the diaphragma and suprasellar portions of the tumor into the operative field. However, complete removal of suprasellar tumor may require a transplanum, transtuberculum approach. Lastly, meningiomas arise from arachnoidal cap cells and are commonly located along the planum sphenoidale (Fig. 20.1C) and tuberculum sellae (Fig. 20.1D). Surgical goals for these tumors are to achieve maximal resection and decompress critical structures (optic nerves) while causing minimal morbidity.

Diagnostic Workup

Diagnostic Workup

A detailed history and physical examination is necessary, including a cranial nerve examination, ophthalmologic evaluation along with visual field testing, assessment of cognitive function, comprehensive endocrine workup, and endoscopic examination of the nasal cavity. Computed tomography (CT) images provide important information about the bony anatomy of the paranasal sinuses and skull base, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is essential to demonstrate the morphology of the soft tissues. Angiography may be indicated preoperatively if carotid artery compromise is suspected or the functional integrity of the circle of Willis requires assessment. CT or MR angiography generally provides sufficient information about the vascular anatomy for surgical planning.

Fig. 20.1 Examples of pathology amenable to extended endonasal endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery that requires removal of the tuberculum sellae and planum sphenoidale. (A) Pituitary macroadenoma with significant suprasellar extension. (B) Craniopharyngioma with large suprasellar cyst above a normal sized sella. (C) Meningioma of the planum sphenoidale. (D) Meningioma of the tuberculum sellae.

Advantages and Indications

Advantages and Indications

The transplanum, transtuberculum approach is well suited to address midline suprasellar lesions, including giant pituitary macroadenomas, Rathke cleft cysts, craniopharyngiomas, meningiomas of the planum sphenoidale or tuberculum sellae, and rare tumors like hemangioblastomas, epidermoids, germinomas, gliomas, and malignant pituitary tumors. More important than the histopathology of the lesion is its location and lateral extension.

The transplanum, transtuberculum approach provides a direct route to these lesions that obviates the need for brain retraction. Also, unlike a transcranial approach, it does not place critical neurovascular structures such as the optic nerves and carotid arteries between the surgeon and the tumor. The transplanum, transtuberculum approach facilitates complete, bilateral optic canal decompression without manipulation of a compressed optic nerve. Moreover, approaching these tumors from below enables the surgeon to remove bone at the base of the tumor, which is a common site for meningioma recurrence, and to interrupt the dural vascular supply early in the operation. This enables a relatively bloodless dissection.

The use of angled endoscopes enables a panoramic view and the ability to inspect around corners to ensure a complete resection. In the case of craniopharyngiomas, the entire third ventricle may be visualized through the endoscope, which is not possible in the transcranial approach. Lastly, the transnasal approach does not require external incisions.

Contraindications and Considerations

Contraindications and Considerations

Patient comorbidities that preclude prolonged anesthesia are general contraindications to any extended transsphenoidal approach. Next, the lateral extent of the tumor must be carefully assessed. The width of the planum sphenoidale, between the laminae papyracea, has been measured in cadaver studies at 26 ± 4 mm, which narrows to 16 ± 3 mm at the posterior aspect of the tuberculum sellae.8 Tumor just lateral to this area can be mobilized into the surgical field; however, significant lateral extension should be approached via a craniotomy if complete resection is the goal. The extended transsphenoidal approach is the preferred corridor when tumor is medial to these structures and optimally exposes the medial aspect of the optic canal. Encasement of critical neurovascular structures such as the optic nerve, internal carotid artery (ICA), and anterior communicating artery (ACA) complex is not an absolute contraindication to this approach. Much like the transcranial approach, the surgeon must judge his or her ability to safely dissect tumor from these structures and must have a plan to address a surgical emergency such as an ICA injury.

The bony pneumatization of the sphenoid sinus is another consideration. In patients with a presellar or conchal-type sinus, bony landmarks for the optic nerves and ICAs are not easily identifiable, and the risk of injury is elevated. In addition, if the sella is small or the distance between internal carotid arteries is narrow, the surgeon may not have adequate surgical access with the transsphenoidal approach. Lastly, patients with poor wound healing capabilities may not tolerate successful skull base reconstruction and are at risk for a persistent cerebrospinal fluid leak. This includes patients with osteoradionecrosis or who suffer from systemic diseases like poorly controlled diabetes mellitus or immunosuppression.

Approach

Approach

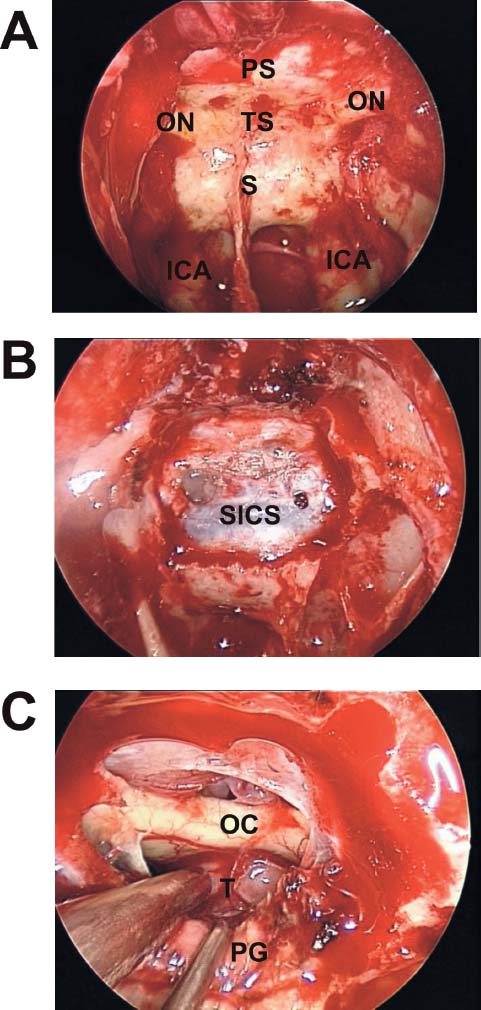

A nasal septal flap can be elevated at the outset of the procedure and tucked in the nasopharynx until the extirpative portion of the procedure is complete. The sphenoid ostia are identified bilaterally and opened widely with a mushroom punch. Next, the posterior third of the bony septum is resected and a piece of vomeric bone is harvested as a rigid buttress for reconstruction of the skull base. The sphenoid rostrum is opened widely with a high-speed cutting drill, and bilateral posterior ethmoidectomies are performed. Mucosa of the sphenoid sinus is removed, and identification of the sella, optic nerves, and ICA is verified with frameless stereotactic image guidance (Fig. 20.2). A 0-degree, 30-cm, rigid 4-mm endoscope is introduced into the left nostril by the assisting surgeon while the primary operating surgeon works bimanually from the right nostril or through both nostrils.

The tuberculum sellae is thinned with a high-speed diamond drill under constant irrigation. The opening extends between the medial clinoids bilaterally. The inferior extent of bony removal continues halfway down into the sella unless mobilization of the pituitary is necessary. The thinned bone is removed with a curette and Kerrison rongeur. Bone removal is continued along the planum sphenoidale until adequate access for complete tumor identification is obtained. The use of stereotactic image guidance helps determine the size of the bony opening. Additional bone should be removed along the optic nerves for meningiomas with intracanalicular involvement.

Fig. 20.2 (A-C) Endoscopic views of the suprasellar approach. Within the sphenoid sinus one can see the bone impressions of the internal carotid arteries (ICA), sella (S), tuberculum sellae (TS), planum sphenoidale (PS), and optic nerves (ON). OC: optic chiasm; PG: pituitary galnd; SICS: superior intercavernous sinus.