Ventral versus Dorsal Approach for Surgical Treatment of Cervical Myelopathy

Sanford E. Emery

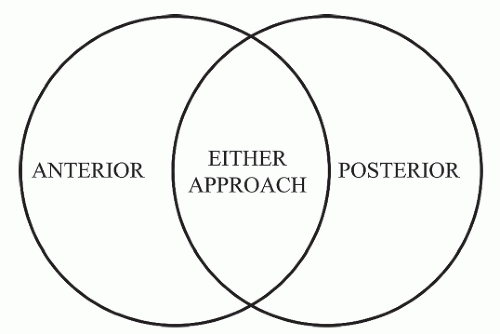

Successful results in spine surgery depend largely on patient selection. This holds true for choosing an operative approach for many patients with cervical stenosis and myelopathy. Both the ventral and dorsal approaches have proven successful, but there are advantages and disadvantages of each that may direct the spine surgeon to one method or the other. Many patients could be successfully treated by either operative approach, where other patients would be much better served by either a ventral or dorsal approach. This can be oversimplified with a Venn diagram as shown in Figure 79.1.

SURGICAL OPTIONS

VENTRAL APPROACH

Goals in treating patients with cervical myelopathy by the ventral approach typically include decompression and stabilization. Depending on the particular patient, this could be successfully performed with a simple anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) or even disk arthroplasty for pathology confined to a single level. Multilevel discectomy and fusion procedures are also satisfactory if the pathoanatomy is confined to the disk space. More commonly in this patient population, however, multilevel corpectomy and strut graft techniques are indicated for severe spondylotic myelopathy or compression caused by ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) (1,2).

DORSAL APPROACH

There are three basic types of surgical techniques for treating cervical stenosis via a dorsal approach: a laminectomy, laminectomy and fusion, or laminoplasty. Laminectomy is the oldest technique yet is uncommon now as a procedure of choice for operative treatment of myelopathy (3). This is largely related to the risk of postlaminectomy kyphosis, which can be difficult though not impossible to manage. Laminectomy with arthrodesis allows for dorsal decompression and stabilization, which prevents postoperative kyphosis or late instability (4). Laminoplasty is arguably the most common technique for dorsal treatment of cervical stenosis, as it provides decompression of the cord, maintains a bony arch for soft tissue healing to minimize kyphotic deformity, and maintains some motion by avoiding arthrodesis (5).

Choosing an Approach: Factors to Consider

Patient Factors

The age and overall health of the patient must be taken into consideration when a surgeon weighs the surgical options. A young healthy patient will likely tolerate either approach. An elderly patient with severe pulmonary disease, however, may be a better candidate for a shorter-duration posterior procedure with less chance of airway issues and prolonged intubation. Similarly, an older patient with medical comorbidities might not tolerate a single-stage three-level cervical corpectomy and strut grafting followed by dorsal instrumentation and fusion; a dorsal approach, be it laminectomy and fusion or laminoplasty, might be better tolerated. Larger ventral procedures with multiple levels involved typically will require some type of postoperative bracing as well, which may or may not influence the surgeon’s decision-making process.

The degree of preoperative neck pain is also a patient factor that should be considered by the spine surgeon. Arthrodesis is probably beneficial in minimizing axial neck pain in these patients since it stops motion at the degenerative levels. Laminoplasty grew in popularity in the 1980s and 1990s because of its ability to decompress the canal, maintain motion by avoiding arthrodesis, and avoid postoperative kyphosis by maintaining a posterior bony arch. In 1996, however, Hosono et al. (6) reported

a substantial incidence (25%) of long-term postoperative neck pain in laminoplasty patients. One study showed that open-door laminoplasty patients had more postoperative neck pain than patients having the French door technique (7). Efforts have been made to institute earlier range of motion exercises for laminoplasty patients and to avoid including the C7 lamina in the canal expansion technique, probably allowing muscle reattachment to the spinous process of C7. These modifications of intraoperative and postoperative treatment for the laminoplasty patient seem to have had a positive influence on decreasing the incidence of postoperative neck pain (8,9). Preoperative axial neck pain, however, is still considered an important patient factor in choosing an approach and specific type of procedure.

a substantial incidence (25%) of long-term postoperative neck pain in laminoplasty patients. One study showed that open-door laminoplasty patients had more postoperative neck pain than patients having the French door technique (7). Efforts have been made to institute earlier range of motion exercises for laminoplasty patients and to avoid including the C7 lamina in the canal expansion technique, probably allowing muscle reattachment to the spinous process of C7. These modifications of intraoperative and postoperative treatment for the laminoplasty patient seem to have had a positive influence on decreasing the incidence of postoperative neck pain (8,9). Preoperative axial neck pain, however, is still considered an important patient factor in choosing an approach and specific type of procedure.

PATHOANATOMY

Some of the most important features in choosing an operative approach for the treatment of cervical myelopathy are related to the pathoanatomy of the cervical spine for that particular patient. Sagittal alignment, that is, the relative lordosis or kyphosis of the cervical spine, is a critical factor in the choice of approach. A kyphotic posture will cause the spinal cord to be draped over the back of the vertebral bodies and disks resulting in ventral compression. Preoperative evaluation should include flexion/extension lateral radiographs to see if this kyphotic deformity is fixed or flexible and, if flexible, how much correction is achieved with extension. This is important since a residual kyphotic deformity typically means residual ventral cord compression, and successful decompression might require a ventral approach (Fig. 79.2 and 79.2). A laminectomy or laminoplasty will certainly enlarge the canal, but in the presence of remaining kyphosis, the cord cannot drift away and thus decompression will not be achieved in this situation (10). The degree of kyphosis that is acceptable for successful dorsal procedures is debated in the literature. Generally speaking, the cervical spine should be at least in a neutral position for the spinal cord to successfully drift dorsally after a dorsal operative procedure (11). However, some authors have suggested up to13 degrees of kyphosis can be tolerated and good outcomes achieved with laminoplasty (12). If the kyphotic deformity is flexible and corrects with extension, then laminectomy plus fusion becomes a viable option since this will maintain lordosis postoperatively and successful neural decompression (13) (Fig. 79.3 and 79.3).

Similar to kyphosis, the shape of the ventral compressive pathology may be important in predicting the adequacy of cord decompression with a posterioronly approach. Disk herniations, osteophytic ridging, or segmental OPLL can be shaped differently for a given patient. Iwasaki et al. (14,15) described two shapes of compressive pathoanatomy: (a) hill-shaped lesions and (b) broad-based or flat lesions. The former will tend to jut into the spinal cord ventrally and can produce a kidney bean-shaped deformity of the spinal cord itself. A more flat ventral compressive lesion tends to produce more circumferential stenosis and symmetric flattening of the ventral cord. In their study, Iwasaki et al. found that hillshaped lesions responded better to ventral decompression techniques (Fig. 79.4 and 79.4) whereas flat or generalized stenosis patients did as well or better with dorsal procedures such as laminoplasty.

Preoperative flexion/extension lateral radiographs can also help identify instability, which is also an important factor in determining the operative procedure. Although the definition of instability could be debated in this setting, subluxation of 2 mm or more would be a contraindication to laminectomy alone and a relative contraindication to laminoplasty techniques. Ventral approaches with fusion or a dorsal decompression plus fusion would be better choices for patients with preoperative instability. Compensatory subluxation at levels above or below the stenotic levels should also be identified as this is important for length of fusion decisions for either operative approach.

In addition to the pathoanatomy features discussed above, the number of disk or vertebral levels involved is an important point to consider in choosing ventral versus dorsal approaches. It has been well documented for ACDF using interbody techniques that the pseudarthrosis rate increases as the number of operative levels increases. Even with modern ventral instrumentation, the nonunion rate for three-level ACDF procedures in two studies remained high at 18% (16) and 53% (17). Strut graft and ventral instrumentation complications become more problematic in three-level versus two-level corpectomy procedures for stand-alone constructs (18,19). Dorsal procedures provide the advantage of longer decompressions without any significant change in technical considerations. For these vthe treatment of cervical myelopathy when the pathology is limited to one or two disk levels (Fig. 79.5) and dorsal procedures for patients with three or more levels of stenosis (Fig. 79.6 and 79.6) (20, 21 and 22). Of course all of the other factors in this discussion must be weighed before choosing the best approach for the individual patient.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree