Abnormalities of Movement

Movement disorders may involve any portion of the body. They usually result from disease involving various parts of the motor system, and the etiologies are many. The character of the movement depends on both the site of the lesion and the underlying pathology. Movement disorders disrupt motor function not by causing weakness but by producing either abnormal, involuntary, unwanted movements (hyperkinetic movement disorders), or by curtailing the amount of normal free flowing, fluid movement (hypokinetic movement disorders).

HYPOKINETIC MOVEMENT DISORDERS

The archetype of hypokinetic movement disorders is Parkinson disease (PD). Other disease processes may produce a similar clinical picture, characterized by decreased movement and rigidity; these have been grouped together as the akinetic-rigid syndromes. About 80% of the instances of akinetic-rigid syndrome are due to PD (Table 21.1). The terms parkinson syndrome or parkinson plus are sometimes used to designate such other disorders, and the features that resemble PD are referred to as parkinsonism, or parkinsonian. Parkinsonism is a clinical diagnosis appropriate in the presence of resting tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity, and impaired postural reflexes. Parkinson disease is but one cause of parkinsonism, and it must be differentiated from other conditions that may have some of its typical features as a component of another disorder.

Parkinson Disease

Parkinson disease is due to a degeneration of neurons in the dopaminergic nigrostriatal pathway. It is the second most common movement disorder behind essential tremor. Cardinal manifestations include bradykinesia, rigidity, tremor, an expressionless face, and postural instability. Asymmetry is characteristic. The disease often begins asymmetrically; the signs may be so lateralized as to warrant the designation of hemi-PD, and some asymmetry usually persists even when the disease is well established. The major manifestations vary from case to case.

Parkinson disease causes marked hypertonia, or rigidity, which principally affects the axial muscles and the proximal and flexor groups of the extremities, causing an increased tone to passive movement. The rigidity has a rhythmic quality referred to as cogwheel rigidity, presumably due to the superimposition of the tremor. Cogwheeling may be brought out as the examiner passively moves an elbow or wrist by having the patient grit the teeth, look at the ceiling, or use the opposite hand to make a fist, trace circles in the air, or imitate throwing a ball. The rigidity is present evenly throughout the range of movement, without the ebb at the extremes of the range that occurs in spasticity.

TABLE 21.1 The Differential Diagnosis of Parkinson Disease | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

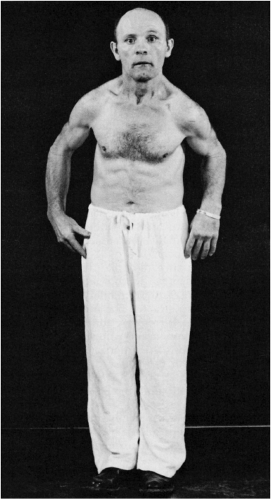

In PD, there is a paucity of movement and a slowing of movements. Strictly speaking, akinesia means an absence of movement, bradykinesia a slowness of movement, and hypokinesia a decreased amount or amplitude of movement, but the term bradykinesia is often used to encompass all three. There is loss of associated and automatic movements, with masking of the face, infrequent smiling and blinking, and loss of swinging of the arms in walking (Figure 21.1).

Patients with PD have poor balance, a tendency to fall, and difficulty walking. The gait abnormality is stereotypical: slow and shuffling with a reduced stride length, sometimes markedly so, a stooped flexed posture of the body and extremities, reduced arm swing, and a tendency to turn “en-bloc.” Impaired postural reflexes lead to a tendency to fall forward (propulsion), which the patient tries to avoid by walking with increasing speed but with very short steps, the festinating gait. Falls are common. If a patient, standing upright, is gently pushed either backward or forward, she cannot maintain balance and will fall in the direction pushed. Facial immobility and lack of expressiveness is a common feature of PD (hypomimia, masked face). A decreased rate of blinking, accompanied by slight eyelid retraction, causes patients to have a staring expression (reptilian stare). The voice is typically soft, breathy, monotonous, and tremulous. Other common manifestations include hyperhidrosis, greasy seborrhea, micrographia, somnolence, difficulty turning over in bed, blepharospasm, and apraxia of eyelid opening. Oculogyric crisis, forced involuntary eye deviation, usually upward, is a feature of postencephalitic PD and can occur in drug-induced parkinsonism, but it does not happen in idiopathic PD. Other common manifestations include foot dystonia, “striatal toe,” an exaggerated glabellar tap reflex (Myerson sign), and impaired handwriting (especially micrographia). Advancing disease is characterized by increasing gait difficulty, worsening of tremor and bradykinesia, motor fluctuations related to levodopa therapy, behavioral changes, cognitive impairment, hallucinations, intractable drooling, and sleep impairment. The impairment of cognition in PD is extremely variable, ranging from minimal involvement to profound dementia. Some degree of cognitive blunting may occur in 20% to 40% of patients. Early, prominent, and nonvisual hallucinations raise the possibility of dementia with Lewy bodies.

FIGURE 21.1 • A patient with Parkinson disease, showing rigidity, masked facies, and typical posture. |

The diagnosis of PD is predominantly clinical, and differential diagnosis essentially is between other conditions causing tremor, of which essential tremor is the commonest, and other akinetic-rigid syndromes. Clinical features that favor PD include prominent rest tremor, asymmetric signs, preservation of balance and postural reflexes in the early stages of the disease, and a good response to levodopa replacement therapy. The other degenerative disorders with parkinsonian features typically produce other neurologic signs, such as gaze limitation, cerebellar signs, pyramidal signs, severe dementia, apraxia and other parietal lobe signs, or dysautonomia, although these other manifestations may not be apparent early in the course. Certain drugs can induce a reversible condition that mimics PD. The most common agents that cause drug-induced parkinsonism are antipsychotics, especially the high-potency piperazine compounds such as haloperidol. Some of the other conditions important in the differential diagnosis of PD include multiple system atrophy, progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, and diffuse Lewy body disease.

Wilson disease (hepatolenticular degeneration) is a rare, autosomal recessive disorder due to abnormal copper deposition in the brain. The usual age of onset is between the ages of 10 and 20, and major manifestations include tremor, rigidity, dystonia and abnormal involuntary movements of various types, dysarthria, dementia, parkinsonian features, spasticity, cerebellar signs, and psychiatric abnormalities (anxiety, depression, psychosis). Kayser-Fleischer rings are crescents of green-brown discoloration of the cornea due to copper deposits in Descemet membrane; these are essentially always present in patients with neurologic involvement but may not be visible without a slit lamp. Hallervorden-Spatz syndrome, or neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation type-1, is a rare, autosomal recessive disorder associated with macroscopic rust-brown discoloration of the globus pallidus and substantia nigra due to iron deposition. The clinical phenotype is variable but usually includes rigidity, involuntary movements, ataxia, and dystonia.

TABLE 21.2 Abnormal Involuntary Movements as a Spectrum of Movements | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

HYPERKINETIC MOVEMENT DISORDERS

Hyperkinesia refers to increased movement. Hyperkinesias are abnormal involuntary movements that occur in a host of neurologic conditions. Hyperkinesias come in many forms, ranging from tremor to chorea to muscle fasciculations to myoclonic jerks. Any level of the motor system, from the motor cortex to the muscle itself, may be involved in their production. The only common characteristic is that the movements are spontaneous and, for the most part, not under volitional control. They may be rhythmic or random, fleeting or sustained, predictable or unpredictable, and may occur in isolation or accompanied by other neurologic signs. Table 21.2 summarizes some of these features.

In the examination of abnormal movements, the following should be noted: (a) the part of the body involved; (b) the extent or distribution of the movement; (c) the pattern, rhythmicity, and regularity; (d) the course, speed, and frequency; (e) the amplitude and force of the movement; (f) the relationship to posture, rest, activity, various stimuli, fatigue, and time of day; (g) the response to heat and cold; (h) the relationship to the emotional state; (i) the degree that movements are suppressible by attention or the use of sensory tricks; and (j) the presence or absence of the movements during sleep. In general, involuntary movements are increased by stress and anxiety and decrease or disappear with sleep. Truly involuntary movements must be separated from complex or bizarre voluntary movements, such as mannerisms or compulsions.

TREMOR

A tremor is a series of involuntary, relatively rhythmic, purposeless, oscillatory movements. The excursion may be small or large, and may involve one or more parts of the body. A simple tremor involves only a single muscle group; a compound tremor involves several muscle groups and may have several elements in combination, resulting in a series of complex movements. A tremor may be present at rest or with activity. Some tremors are accentuated by having the patient hold the fingers extended and separated with the arms outstretched. Slow movements, writing, and drawing circles or spirals may bring tremor out.

Tremors may be classified in various ways: by location, rate, amplitude, rhythmicity, relationship to rest and movement, etiology, and underlying pathology. Other important factors may include the relationship to fatigue, emotion, self-consciousness, heat, cold, and the use of medications, alcohol, or street drugs. Tremor may be unilateral or bilateral and most commonly involves distal parts of the extremities—the fingers or hands—but may also affect the arms, feet, legs, tongue, eyelids, jaw, and head, and may occasionally seem to involve the entire body. The rate may be slow, medium, or fast. Oscillations of 3 to 5 Hz are considered slow, 10 to 20 Hz rapid. Amplitude may be fine, coarse, or medium. Tremor may be constant or intermittent, rhythmic or relatively nonrhythmic, although a certain amount of rhythmicity is implied in the term tremor. Irregular “tremor” may be due to myoclonus.

The relationship to rest or activity is the basis for classification into two primary tremor types: rest and action. Resting (static) tremors are present mainly during relaxation (e.g., with the hands

in the lap), and attenuate when the part is used. Rest tremor is seen primarily in PD and other parkinsonian syndromes. Action tremors appear when performing some activity. Action tremors are divided into subtypes: postural, kinetic, task-specific, and isometric. Only when they are very severe are action tremors present at rest. Postural tremors become evident when the limbs are maintained in an antigravity position (e.g., arms outstretched). Common types of postural tremor are enhanced physiologic tremor and essential tremor (ET). Kinetic tremor appears when making a voluntary movement, and may occur at the beginning, during, or at the end of the movement. The most common example is an intention (terminal) tremor. Intention tremor is a form of action tremor seen primarily in cerebellar disease. The tremor appears when precision is required to touch a target, as in the finger-nose-finger or toe-to-finger test. It progressively worsens during the movement. Approaching the target causes the limb to shake, usually side-to-side perpendicular to the line of travel, and the amplitude of the oscillation increases toward the end of the movement. Some tremors fall into more than one potential classification. Most tremors are accentuated by emotional excitement, and many normal individuals develop tremor with anxiety, apprehension, and fatigue.

in the lap), and attenuate when the part is used. Rest tremor is seen primarily in PD and other parkinsonian syndromes. Action tremors appear when performing some activity. Action tremors are divided into subtypes: postural, kinetic, task-specific, and isometric. Only when they are very severe are action tremors present at rest. Postural tremors become evident when the limbs are maintained in an antigravity position (e.g., arms outstretched). Common types of postural tremor are enhanced physiologic tremor and essential tremor (ET). Kinetic tremor appears when making a voluntary movement, and may occur at the beginning, during, or at the end of the movement. The most common example is an intention (terminal) tremor. Intention tremor is a form of action tremor seen primarily in cerebellar disease. The tremor appears when precision is required to touch a target, as in the finger-nose-finger or toe-to-finger test. It progressively worsens during the movement. Approaching the target causes the limb to shake, usually side-to-side perpendicular to the line of travel, and the amplitude of the oscillation increases toward the end of the movement. Some tremors fall into more than one potential classification. Most tremors are accentuated by emotional excitement, and many normal individuals develop tremor with anxiety, apprehension, and fatigue.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree