Chapter 29 Arm and Neck Pain

Clinical Assessment

History

Neurological Causes of Pain

Plexus Pain

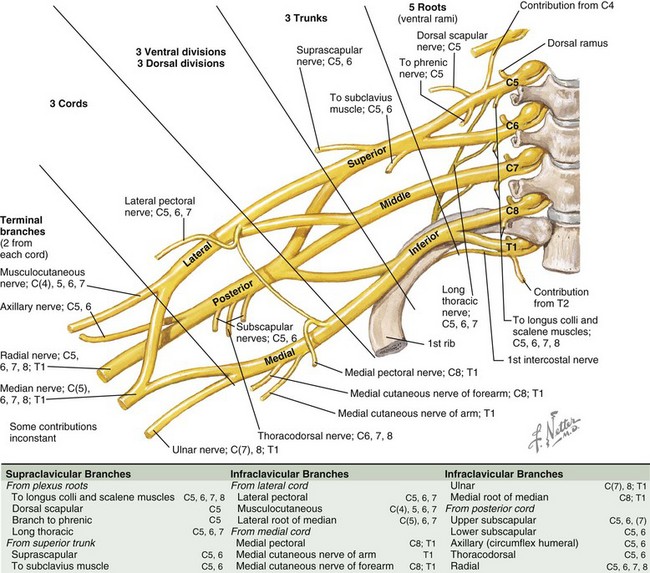

Peripheral pathology may involve the brachial plexus (Fig. 29.1) or individual nerves extending to the hand. Infiltrative or inflammatory lesions of the brachial plexus produce severe brachialgia radiating down the upper limb and also spreading to the shoulder region. Radiation to the ulnar two fingers suggests that the origin is in the lower brachial plexus, and radiation to the upper arm, forearm, and thumb suggests an upper plexopathy. Patients with a thoracic outlet syndrome complain of brachialgia and numbness or tingling in the upper limb or hand when working with objects above the head.

Examination

Motor Signs

The distribution of weakness is all important in localizing the problem to nerve root, plexus, peripheral nerve, muscle, or even upper motor neuron (central weakness). It is useful to use a simplified schema of radicular anatomical localization when evaluating nerve root weakness because overlap of segmental innervation of muscles can complicate the analysis (Table 29.1).

Table 29.1 Segmental Innervation Scheme for Anatomical Localization of Nerve Root Lesions

| Segment Level | Muscle(s) | Action |

|---|---|---|

| C4 | Supraspinatus | First 10 degrees of shoulder abduction |

| C5 | Deltoid | Shoulder abduction |

| Biceps/brachialis/brachioradialis | Elbow flexion | |

| C6 | Extensor carpi radialis longus | Radial wrist extension |

| C7 | Triceps | Elbow extension |

| C7 | Extensor digitorum | Finger extension |

| C8 | Flexor digitorum | Finger flexion |

| T1 | Interossei | Finger abduction and adduction |

| Abductor digiti minimi | Little finger abduction |

Sensory Signs

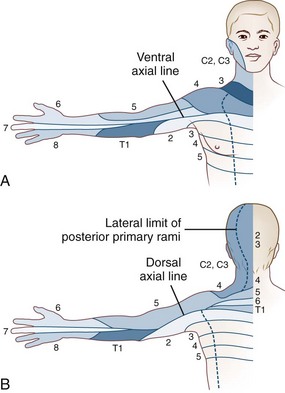

Skin sensation is tested in a standardized manner starting with pinprick appreciation at the back of the head (C2), followed by sequentially testing sensation in the cervical dermatomes, down the shoulder, over the deltoid, down the lateral aspect of the arm to the lateral fingers, and then proceeding to the medial fingers and up the medial aspect of the arm (Fig. 29.2). The procedure is repeated with a wisp of cotton to test touch sensation and test tubes filled with cold and warm water to test temperature sensation. Vibration sense is rarely abnormal in the fingers. Position sense in the distal phalanx of a finger is tested by immobilizing the proximal joint and supporting the distal phalanx on its medial and lateral sides and then moving it up or down; the patient, with closed eyes, reports movement and its direction. Loss of position sense in the fingers usually indicates a very high cervical cord lesion.

Pathology and Clinical Syndromes

Spinal Cord Syndromes

Extramedullary Lesions

Extramedullary lesions may result in any combination of root, central cord, and long-tract signs and symptoms. The most common cause of extrinsic nerve root and spinal cord compression is cervical spondylosis. This is a degenerative disorder of the cervical spine characterized by disc degeneration with disc space narrowing, bone overgrowth producing spurs and ridges, and hypertrophy of the facet joints, all of which can compress the cord or nerve roots. Hypertrophy of the spinal ligaments, with or without calcification, may contribute to compression. Hypertrophic osteophytes are present in approximately 30% of the population, and the incidence increases with age. The presence of such degenerative changes does not indicate that the patient has symptoms due to these changes; astuteness in diagnosis is necessary. Furthermore, the degree of bony change does not always correlate with the severity of the signs and symptoms it produces. This degenerative process is sometimes referred to as hard disc as opposed to an acute disc herniation or soft disc in which the onset is acute with severe neck pain and brachialgia. Patients with cervical spondylosis often awake in the morning with a painful stiff neck and diffuse nonpulsatile headache that resolves in a few hours. The lesion is most commonly at C5/6 and C6/7, and focal signs are likely to be at these levels. Wasting and weakness of the small muscles of the hands, particularly weakness of abduction of the little finger, is also frequently seen. These signs localize to lower segmental levels, but there may be no observable anatomical change at those levels, and then they are referred to as false localizers. Restricted neck movement is always present with significant cervical spondylosis. Bladder dysfunction, indicated by frequency, urgency, and urgency incontinence or the finding of long-tract signs or symptoms, indicates the need for imaging of the cervical spine both to exclude other pathology and to define the severity of the spinal cord compression. Immobilization in a cervical collar often helps with the symptoms and signs of cervical spondylosis. The role of surgery in treatment is discussed in Chapter 75.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree