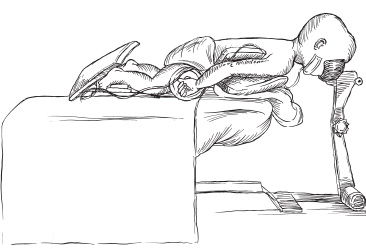

Neoplasms Brain tumors that arise in infants during the first 2 years of life may be congenital, developmental, or identical to the lesions that affect older children or adults. Although they are rare, affecting only 1.1 of every 100,000 liveborn or stillborn infants, brain tumors are the most common solid tumors occurring in young children. Of all intracranial tumors affecting infants, most are astrocytomas (32%), primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNETs, 25%), ependymomas (12%), or choroid plexus papillomas (10%) (Fig. 10–1). An aggressive surgical approach that maximizes the extent of surgical resection is essential to the treatment of brain tumors during an infant’s first 2 years of life because radiation therapy, the most effective adjuvant treatment for older children and adults, is harmful to the immature nervous system. Surgical resection or biopsy is the initial therapy of choice for infants with brain tumors of all types except diffuse pontine or hypothalamic glioma without exophytic components, optic-nerve glioma in infants with excellent vision or neurofibromatosis, or subependymal giant-cell astrocytoma without symptomatic ventriculomegaly in a child with tuberous sclerosis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed with and without gadolinium contrast agent is indicated in nearly all cases. In our experience, sedation is the most important variable in obtaining high-quality diagnostic magnetic resonance images. To avoid hypoventilation-induced increases in intracranial pressure, sedation is accomplished most safely by using general anesthesia and controlled ventilation. Computed tomography done without contrast agent is useful in screening for intracranial masses in meganencephalic infants who have no neurologic deficit; if a mass is found in such patients, however, MRI should be performed. Nearly all patients require some degree of preoperative management for increased intracranial pressure, associated hydrocephalus, or seizures. Increased intracranial pressure may result from mass effect of the tumor and hydrocephalus caused by obstruction of cerebrospinal fluid drainage. Corticosteroids relieve increased pressure from the mass effect. The timing of extraventricular drainage for hydrocephalus is determined by the patient’s clinical condition; children who are obtunded or comatose undergo emergency extraventricular drainage. Normal intracranial pressure varies according to age: Physiological intracranial pressure in a neonate (<2 mm Hg) is lower than that in infants up to 1 year of age (1.5 to 6 mm Hg) and in turn is lower than that in young children (3–7 mm Hg). Preoperative management of seizures begins with routine use of antiepileptic drugs. In the event the patient has controlled, nongeneralized seizures and is not being medicated already for seizure prophylaxis, an intravenous loading dose should be given in the operating room at the time of surgery and continued postoperatively. Patients with intractable seizures who are not taking antiepileptic drugs should be given them preoperatively and the patient’s response monitored. If seizures are refractory to antiepileptic drugs, even though the patient is verified to have received a therapeutic concentration, an electroencephalogram should be performed preoperatively to lateralize and help localize the epileptogenic focus, and preparations should be made for the intraoperative mapping of seizure foci by means of electrocorticography or evoked potentials. In contrast, there is no indication for intraoperative electrocorticography for patients whose seizures are well controlled because the tumor is nearly always the focus in these cases, and tumor resection is likely to leave the patient seizure free. In the operating room, warming pads, heated fluid bags, and an elevated room temperature are used to maintain the patient’s normal physiologic temperature. Intravenous access is established by using an angiocatheter when possible; however, a saphenous vein cut-down sometimes is required. The urinary bladder is catheterized by using a pediatric urinary bladder catheter without a balloon. Patients are positioned appropriately for the operation, with the limbs partially flexed and all pressure points padded (Fig. 10–2). The patient’s head is placed on a foam headrest or padded doughnut-shaped cushion because the skull of children younger than 2 years of age may deform or fracture if pin fixation is attempted. The endotracheal tube then is fastened into place because even slight pressure may dislodge it during the operation. Special care is taken to cover the endotracheal tubing with towels to prevent the skin drapes from adhering to the tubing and perhaps inadvertently dislodging the endotracheal tube when the drapes are removed. After superficial skin incision of the scalp, bleeding is prevented by direct pressure from the surgeon. The incision is continued by using electrocautery (Bovie) or a contact laser. Alternatively, the Shaw scalpel, which uses heat for hemostasis, may be used to incise the skin and subcutaneous tissues. Moistened towels are placed along the edges of the scalp incision and secured in place with Michele clips; in addition to protecting the tissue, these sponges make any ongoing bleeding sites apparent. Rainey clips are generally too large for use in infants; when they do fit, they apply such excessive force that they may cause necrosis in delicate infant tissues. If the fontanelles remain open, craniotomy may be performed without the necessity of a burr hole by using the fontanelle to gain access to the epidural space. In young infants, bone often can be cut with scissors; however, a pneumatic drill with a side-cutting bit is often necessary.

SURGICAL INDICATIONS AND PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

PREOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

INTRAOPERATIVE TECHNIQUES

Anesthesia and Positioning

Surgery

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree