9 Classification of Endonasal Approaches to the Ventral Skull Base

Carl H. Snyderman, Harshita Pant, Ricardo L. Carrau, Daniel M. Prevedello, Paul A. Gardner, and Amin B. Kassam

Introduction

Introduction

We live in an era of minimally invasive surgery where many traditional open surgical approaches are being replaced by endoscopic approaches. In otolaryngology, endoscopic sinus surgery has become the standard of care for the treatment of inflammatory diseases and many benign and malignant sinonasal tumors. In neurosurgery, endoscopes have had a limited role and have been primarily used as an adjunct to open microscopic procedures, including surgery for pituitary tumors,1,2 posterior fossa nerve decompression, and intracranial aneurysms. In recent years, otolaryngologists and neurosurgeons have collaborated to apply endoscopic principles to the treatment of cranial base tumors.3 Development of endonasal cranial base surgery required an understanding of the skull base anatomy from an endoscopic perspective, the development of technologies adapted for intranasal use, and the concept of team surgery with an otolaryngologist and a neurosurgeon operating simultaneously and synergistically.

Introducing a new surgical concept often has three main phases of development: technical feasibility, safety and complications, and treatment outcomes. A critical examination of the outcomes begets new innovations or modifications of techniques, and this cycle repeats itself. We previously reported on the technical aspects of endonasal surgery of the cranial base and described new endoscopic surgical approaches to the ventral skull base.4–6 Our experience over the last decade with more than 1000 entirely endoscopic surgeries demonstrated that endonasal cranial base surgery can be performed with acceptable morbidity. Reporting of treatment outcomes requires verification and comparison of experiences at multiple medical centers. A comparison of surgical series is made difficult by the variety of surgical approaches to the ventral skull base, diverse pathology and biology, and lack of standard measures of outcome.

Endonasal surgery of the cranial base began with pituitary surgery1,2 and gradually progressed to encompass neighboring regions of the cranial base. It became apparent that the sphenoid sinus was the starting point for access to most of the cranial base and it contained the most critical anatomical structures, including the optic nerves and internal carotid arteries (ICAs). A surgical extension from the sphenoid sinus to adjacent areas of the ventral skull base can proceed in all directions with basic orientation along the sagittal and coronal planes. Thus, the ventral skull base can be divided into modular units that can be approached individually or in combination to provide access to various pathologic processes.4–6

As endonasal techniques evolve and become more widespread, a classification scheme is necessary to facilitate effective teaching of these techniques, preoperative planning, comparison of reported surgical series, and to refine surgical techniques. Here, we report our classification system based on our surgical experience with endonasal skull base surgery.

Methods

Methods

A retrospective analysis of all patients undergoing endonasal skull base surgery for all types of pathology at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center from 1998 to 2006 was performed. A tumor registry was maintained on all patients with approval of the medical center’s institutional review board. The ventral skull base was divided into anatomical subunits based on the relationship of these to key anatomical structures such as the internal carotid artery, cavernous sinus, optic nerve, and bony landmarks.

The classification scheme is shown in Table 9.1. In the sagittal plane, these endoscopic approaches extend anteriorly to the frontal sinus, inferiorly to the second cervical vertebra, and laterally to the jugular foramen and parapharyngeal carotid artery. It is useful to subcategorize the approaches in the coronal plane that correspond to the anterior, middle, and posterior cranial fossae. The anterior coronal plane extends from the midline across the roof of the orbits. The middle coronal plane includes the cavernous sinus, petrous apex, Meckel’s cave, and the infratemporal skull base that is above the level of the petrous ICA. The posterior coronal plane includes the occipital condyle, extends along the inferior surface of the petrous bone below the level of the petrous ICA to the jugular foramen, and includes adjacent extracranial structures (parapharyngeal space).

Sagittal plane Transfrontal Transcribriform Transplanum (suprasellar) Transsellar Transclival Superior: dorsum sellae Middle: midclivus Inferior: foramen magnum Transodontoid Coronal plane Anterior (anterior cranial fossa) Supraorbital Transorbital Middle (middle cranial fossa) Transpterygoid Transcavernous Medial Lateral Medial petrous apex Suprapetrous (middle fossa) Meckel’s cave Infratemporal skull base Posterior (posterior cranial fossa) Transcondylar Infrapetrous Parapharyngeal space Medial (jugular foramen) Lateral |

Surgical Approaches

Surgical Approaches

More than 1000 endonasal skull base procedures were performed for a variety of pathologic processes including intracranial and extracranial neoplasms. For the purpose of this study, the first 700 patients were included. Although the largest number of patients had pituitary adenomas (39%), the majority of these were macroadenomas with extrasellar extension. There were more than 50 pediatric patients (<18 years). Approximately 23% were younger than 35 years and 25% were older than 62 years.

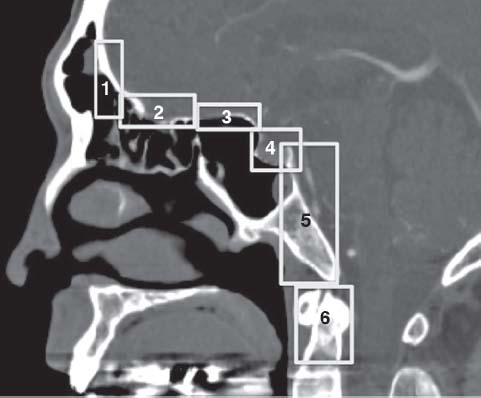

Using the classification scheme shown in Table 9.1, surgical approaches were categorized according to the predominant approach (Fig. 9.1). The sphenoid sinus was selected as a starting point for most endonasal procedures because of the key anatomical structures surrounding the sinus: ICA, optic nerves and chiasm, cavernous sinus, pituitary gland, and basilar artery. Many patients required surgical access via multiple anatomical modules, depending on the extent of the pathology and the need to expose key anatomical structures for tumor resection.

Fig. 9.1 Distribution of EEA surgical approaches. Some of the surgical approaches are grouped. 1: transfrontal; 2: transcribriform; 3: transplanum; 4: transsellar; 5: transclival; 6: transodontoid.

Fig. 9.2 Computed tomography (CT) scan at the sagittal plane of a nasal dermoid cyst with a tract extending through the skull base at the foramen cecum. This is an example of a disease treated with a transfrontal approach.

Sagittal Plane

Transfrontal Approach (Fig. 9.2)

A transfrontal approach accesses the anterior cranial fossa. It starts by bilateral frontal recess clearance, an access via the superior septal window to facilitate a modified endoscopic Lothrop (MEL) or a Draf 3 procedure in which a single maximum- sized frontal sinus ostium is created. Dissection posterior to the attachment of the middle turbinate to the skull base preserves olfaction and avoids violation of the cribriform plate and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak. Common pathologies requiring a transfrontal approach include chronic frontal sinusitis, frontal sinus mucocele, fibro-osseous tumors, and nasal dermoid cysts. In pediatric patients with dermoid cysts, the cyst is opened intranasally and the septum is resected up to the skull base. Bone surrounding the sinus tract is drilled to the level of the dura with complete removal of epithelium lining the cyst.

Transcribriform Approach (Fig. 9.3)

The final surgical resection with this approach is analogous to the classic craniofacial resection. The cribriform plates are commonly resected for sinonasal malignancies (including esthesioneuroblastoma) and olfactory groove meningioma. First, the intranasal portion of the tumor is debulked to the plane of the skull base to define the attachment to the cribriform plate, and this attachment is cauterized with bipolar electrocautery. A complete sphenoethmoidectomy is performed bilaterally and a Draf 3 procedure performed to define the anterior resection margin. The nasal septum is transected along the sagittal plane from the crista galli anteriorly to the sphenoid rostrum approximately 1 cm inferior to the tumor attachment to the septum. This defines the inferior resection margin. The tumor is devascularized by cauterizing and transecting the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries, along the fovea ethmoidalis, midway along its course from the orbital margin and lateral lamella. The bone of the anterior cranial base in the periphery of the tumor is thinned with a coarse diamond drill to the resection margins, anteriorly to the posterior table of frontal sinus, posteriorly to the planum sphenoidale, and laterally to the medial orbital walls. The thinned bone is gently fractured and elevated inferiorly off the overlying dura.

The dura is cauterized and incised longitudinally along the lateral orbital margins, taking care to avoid injury to cortical vessels. The crista galli is removed with a drill, and the attached falx cauterized and transected. This facilitates rotating the dural specimen posteriorly. Dural incision along its posterior margin allows removal of the entire dural specimen en bloc. When indicated, the olfactory bulbs and nerves are elevated inferiorly off the overlying brain and transected at the level of the posterior dural margin. In the sagittal plane, the surgical defect extends from the posterior table of the frontal sinus to the planum sphenoidale and along the coronal plane, to the medial wall of the orbit on either side. For selected cases with small ipsilateral tumors, an ipsilateral resection of the anterior cranial base with preservation of olfaction on the contralateral side can be performed.

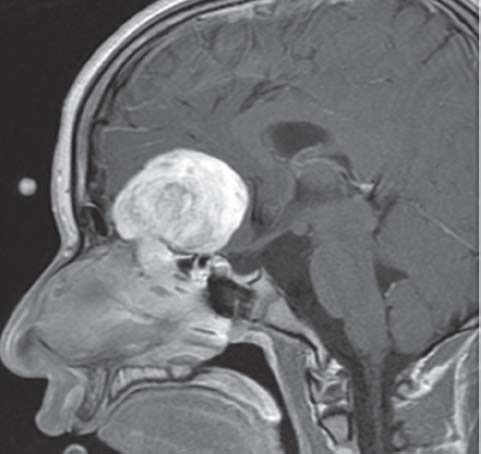

Fig. 9.3 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of a large olfactory groove schwannoma that was completely resected using an endonasal transcribriform approach.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree