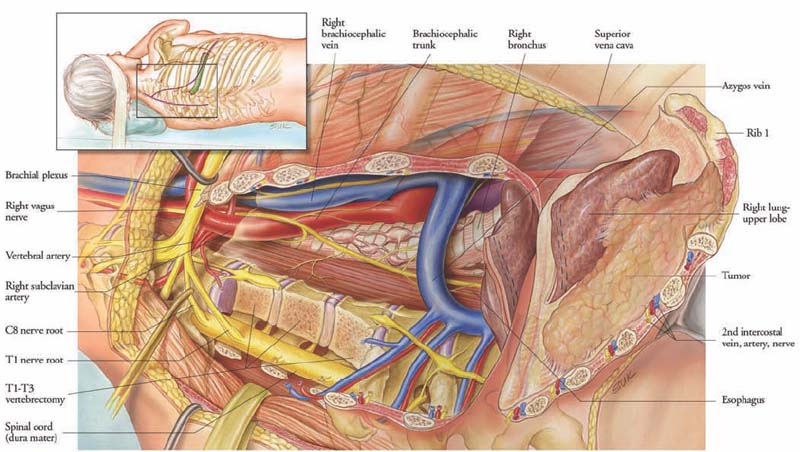

29 In 1924, Pancoast1 described a series of apical chest tumors that were characterized by pain, Horner’s syndrome, bone destruction, and atrophy of the hand muscles. Pancoast wrongly believed that the tumor arose from embryonic rests. In 1932, Tobias2 clearly defined the syndrome and attributed its cause to bronchogenic carcinoma. The majority of cases of superior sulcus, or Pancoast tumors, are non-small-cell bronchogenic carcinoma, most commonly squamous cell, followed by adenocarcinoma and large cell carcinoma.3 These tumors can invade the lower roots of the brachial plexus, sympathetic chain, mediastinal structures, spinal column, and adjacent ribs and chest wall. Before 1950, this tumor was uniformly fatal; however, with earlier clinical diagnosis, advances in imaging of the chest and spinal column, and more aggressive surgical and medical therapy, the dismal prognosis has improved.4 The tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) classification of the American Joint Committee on Cancer defines a T3 tumor as a tumor of any size that directly invades the chest wall or mediastinal pleura. T4 is a tumor of any size that invades any part of the mediastinum, great vessels, or vertebral body. This chapter reviews the current management of superior sulcus tumors, with a focus on tumors involving the vertebral column. The majority of patients are diagnosed in the fifth or sixth decades of life. The most common initial symptom is shoulder pain, which results from neoplastic involvement of the brachial plexus, parietal pleura, vertebral bodies, or ribs.5 Pain can radiate up to the head and neck or down the medial aspect of the upper extremity. Delays in diagnosis of 5 to 10 months are not uncommon. Horner’s syndrome, which consists of ipsilateral ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis, is caused by invasion of the paravertebral sympathetic chain and the inferior cervical ganglion. Weakness and atrophy of the intrinsic muscles of the hand may occur, along with pain and paresthesia of the medial aspect of the arm, forearm, and fourth and fifth digits. With extension of tumor through the intervertebral foramen or involvement of the vertebral bodies, compression of the spinal cord may occur. Findings on plain chest radiographs include an apical mass and bone destruction. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest provides additional information regarding the extent of tumor involvement and is helpful in identifying other pulmonary nodules, parenchymal disease, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is as effective as CT in detecting mediastinal lymph node involvement and is superior to CT in detecting tumor invasion of the brachial plexus, vertebral bodies, spinal canal, and subclavian vessels.3 Distant metastatic spread should be evaluated based on the patient’s history, physical examination, and blood tests. CT of the chest and abdomen and bone scanning should be considered. CT or MRI of the brain must be part of the metastatic workup, because of the high incidence of brain metastases with bronchogenic carcinoma in this location. The treatment of patients who harbor locally advanced Pancoast tumors remains controversial. Although the results of multiple studies have proved the utility of performing gross-total resection in patients with less extensive disease, many surgeons believe that when these tumors advance to the point that they involve the great vessels, trachea, esophagus, or vertebral bodies, complete resection is either not warranted or not feasible.6–11 In reviewing the literature, it is important to realize that the majority of published studies on superior sulcus tumors were conducted prior to the availability of complex thoracic vessel reconstruction and spinal reconstruction techniques. Most of the series do not include patients with extensive local invasion, and therefore it is difficult to compare their results with those of current studies. The management of superior sulcus tumors has evolved over the past 50 years. In the early 1950s this disease was considered to be inoperable and was uniformly fatal.4 In 1954, the first therapeutic breakthrough was realized when Haas et al12 initiated radiation treatment in the management of these thoracic neoplasms. Patients had dramatic relief of their arm pain, and nine patients survived 5 years following radiation therapy. The first successful treatment of a superior sulcus tumor by surgery and postoperative radiotherapy was reported by Chardack and MacCallum.13 Their patient underwent resection followed by 65 cGy of irradiation. In 1961, Shaw et al14 published results of the combined use of preoperative radiation and surgery in 18 patients. Subsequently, Shaw, Paulson, and others found that preoperative radiation facilitated surgical resection and that this approach was associated with a 30% 5-year survival.6,15,16 Since that time, preoperative radiation and surgical resection have become the standard management of superior sulcus tumors. The potential benefits of preoperative radiation include a decrease in the size of tumor, with improved resectability, and a reduction in the number of viable tumor cells. In 1987, Wright et al11 studied 21 patients who underwent combined therapy with irradiation and radical resection. Median survival was 2 years, and actuarial survival rate was 55% at 3 years and 27% at 5 years. A review of 225 patients operated on from 1974 to 1998 for superior sulcus tumors at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center indicated that actuarial survival at 5 years was 46% for stage IIB, 0% for stage IIIA, and 13% for stage IIIB tumors.17 Survival was influenced by tumor (T) and node (N) status and completeness of resection. Resection was considered pathologically complete in only 64% of T3N0 and 39% of T4N0 tumors. Locoregional disease was the most common form of relapse, occurring in 40% of patients. Within this series, the more recent experience encompassing the years 1992 to 1998 did not differ substantially from the earlier years. The prognosis of patients with superior sulcus tumors appears to be related to several clinical factors. Factors that have traditionally been associated with a poor prognosis in most series include extension of the tumor into the base of the neck; involvement of the mediastinal lymph nodes, vertebral bodies, or great vessels; the presence of Horner’s syndrome; and longer duration of symptoms.18–21 Clinical factors associated with improved survival include good performance status, a weight loss of less than 5% of total body weight, and achievement of local control and pain relief after treatment.3 Anderson et al22 reported that positive margins, N2 disease, and vertebral body involvement were associated with a poorer prognosis. Ginsberg et al6 found Horner syndrome, N2 and N3 disease, T4 disease, and incomplete resection to be adverse prognostic factors. Okubo et al23 found incomplete resection influenced prognosis, particularly tumor invasion into the brachial plexus. Muscolino et al24 indicated that involvement of the first rib, the vertebral body, invasion of the great vessels, and N2 disease all had a very poor prognosis, and these patients should not undergo surgery. Because incomplete resection is often cited as a poor prognostic factor, recent surgical series have focused on exploring the use of extended operations to achieve complete resection of T4 tumors that invade the subclavian vessels or spinal column. Several series have highlighted the benefit of a multidisciplinary approach to locally aggressive tumors that can only be removed by formal spine resection and stabilization. The approach that has been developed at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center is presented in the next section. Conventional posterior thoracotomy as described by Paulson does not provide sufficient exposure of vascular and neurologic structures in locally advanced tumors. The transclavicular cervicothoracic route provides good vascular exposure but is inadequate when extensive lung parenchymal excision is required or spinal involvement is present.25,26 DeMeester et al27 were among the first to describe a technique for resecting tumors that are adherent to the spine. Through an extended posterolateral thoracotomy, they performed a tangential osteotomy at the junction of the pedicle and the costal facet. The entire tumor, including the involved portions of the chest wall, lung, and vertebral body, was then removed en bloc. In two reports, Grunenwald and associates28,29 described an innovative technique in which a total vertebrectomy is performed for en bloc resection of superior sulcus tumors that invade the vertebral column. They initially performed a three-step procedure: an anterior cervical approach, a posterolateral thoracotomy, and, finally, a posterior approach. During the third stage, the spinal column was transected using a Gigli saw to cut the vertebral end plates, thus allowing the tumor to be removed en bloc. The vertebral column was reconstructed anteriorly with autologous clavicle graft and with the placement of plates and screws posteriorly. More recently, Grunenwald has described a two-stage procedure, consisting of an anterior cervicothoracic and posterior midline approach that achieves the same goal. The original report by these authors included results on two patients who underwent total vertebrectomy for en bloc resection of Pancoast tumors.28 One patient experienced local recurrence 18 months later, and the other patient died 5 months following surgery. An updated report included 12 patients in whom surgery was performed for Pancoast tumors, although it is unclear how many patients required total vertebrectomy.29 At the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, we have developed a technique for resecting superior sulcus tumors that invade the chest wall and spinal column. Our experience with this multidisciplinary approach to superior sulcus tumors involving the vertebral column has been documented in the literature.30,31 The surgical procedure is illustrated in Figs. 29-1, 29-2, and 29-3. After induction of general anesthesia and intubation of the patient with a double-lumen endotracheal tube, correct positioning is verified bronchoscopically. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy also allows visualization of subsegmental pulmonary levels to assess endobronchial disease. Mediastinoscopy and lymph node biopsy may also be performed to assess for nodal involvement. The patient is then placed in a lateral decubitus position with the head secured in a Mayfield head holder. An extended standard posterolateral thoracotomy is performed, and the chest cavity is entered. In cases of peripherally situated tumors, the apical segment of the upper lobe of the lung is separated from the remaining superior lobe using a GIA-75 stapler (Ethicon Endosurgery, Cincinnati, OH). At this point, the apex of the lung is left attached to the chest wall. The first through third, fourth, or fifth ribs are then sectioned anteriorly. The subclavian artery is sharply dissected from the surrounding structures. A subperiosteal dissection is then performed around the first rib, which is transected, and the subclavian vessels are mobilized superiorly. If, as visualized on the preoperative MRI, the vessels are involved, an initial anterior approach is performed to dissect or graft the vessels. A posterior midline incision is then made, which is connected to the thoracotomy incision. This creates a triangular skin flap, which should be fashioned so that its base is as wide as possible to avoid vascular compromise and healing difficulties. Laminectomies are performed to expose the epidural tumor and nerve roots.

Combined Vertebrectomy and Chest Wall Resection for Pancoast Tumors

Clinical Presentation

Clinical Presentation

Radiologic Findings

Radiologic Findings

Management Options

Management Options

Surgical Approach

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree