(a) Bilateral pontine and left temporo-occipital infarcts on diffusion-weighted imaging consistent with acute infarct in basilar artery and posterior cerebral artery territories. (b) Dense basilar artery on initial CT head (arrows).

Discussion

Basilar artery occlusion is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, especially in the absence of recanalization [6]. Identifying basilar artery thrombosis can be challenging and confusing. The symptoms may vary from very mild presentations such as slurred speech to very severe ones such as coma; in other patients, symptoms may be vaguely characterized or bizarre (i.e., behavioral symptoms such as agitated delirium or hallucinosis). Some patients may present with focal deficits initially and cause clinicians to consider lacunar or hemispheric localization. The so-called herald hemiparesis that was described by C. Miller Fisher refers to such a presentation whereby initial hemiparesis leads subsequently to bilateral symptoms including locked-in state, coma, or death [7]. Greater recognition and urgency in stuttering or gradual onset presentations are critical to early diagnosis and management of this condition.

Not uncommonly, cognitive anchoring can occur in acute neurologic diagnostic formulation when clinicians over-emphasize certain details of the presentation and/or ignore others, having already approached the patient with preconceived biases and expectations [8]. In this instance, the presumed diagnosis in a young, previously healthy woman who is unresponsive and posturing is often seizures or toxic exposure. While this patient displayed no seizure activity (i.e., actual convulsions), it should be noted that extensor posturing can be frequently confused with seizures by untrained witnesses and even physicians [9].

Several other clinical clues, however, suggested basilar artery thrombosis. First, fixed pinpoint pupils and limited upgaze are indicative of pontine and midbrain injury, respectively. This should not be confused with pinpoint pupils that are observed with opiate intoxication. A rapid urine drug screen could exclude drug intoxication. Second, dysconjugate and skewed gaze is unusual in supratentorial or diffuse cerebral disorders such as hemispheric stroke, metabolic disturbances, and seizures. In seizures, conjugate gaze abnormalities are notable either in the active or ictal phase (away from the seizure focus) or in the post-ictal phase (toward the seizure focus if a Todd’s paralysis is occurring). Lastly, formal neurologic assessment should include detailed brainstem function testing such as papillary, corneal, oculocephalic, oculovestibular, gag, and cough reflex testing in addition to motor response testing with noxious stimulation. These would localize the presentation to the bilateral pons in this patient.

Rapid imaging with CT head is essential to exclude hemorrhage and evaluate for early ischemic signs in the brainstem, cerebellum, thalami, and/or occipital lobes, and also assess for basilar artery thrombosis by dense artery identification. If early ischemic changes are present, these would indicate duration of ischemia of at least 6 hours duration. If CT head is normal, further imaging with MRI brain and MRA head and neck, if emergently available, or CT angiography of the head and neck, are mandatory. In this case, CT head was negative for hemorrhage but further review suggested a dense basilar artery was indeed present on the initial scan (Figure 7.1b).

Had the diagnosis of ischemic stroke been made in this case, the patient would have been eligible for intravenous thrombolysis with tPA. Though poor outcome (modified Rankin scale 4–6) occurred in more than two-thirds of patients, a recent prospective study found that IV tPA reduced the odds of poor outcome by 20% compared to antithrombotic therapy and was equivalent to intra-arterial or endovascular therapy [10]. These data suggest that recognition, early diagnosis, and thrombolytic treatment could reduce the disability and death associated with basilar artery thrombosis.

Tip

Diagnostic suspicion for basilar artery thrombosis should be high in any presentation of coma and tetraparesis given the high morbidity and mortality associated with the condition. Delay in diagnosis or misdiagnosis can have grave consequences. IV tPA, if provided within 3 hours, can improve outcomes and is recommended in all patients with suspected basilar artery thrombosis. Intra-arterial therapy is also reasonable and should be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Case 3. Rapidly improving symptoms

Case description

A 65-year-old woman with hypertension and diabetes presented with right hemiparesis that had been fluctuating since onset 1 hour earlier. Initially, she had stumbled to the floor at her home due to right leg weakness, noted her arm and leg could not move for 10 minutes, and then improved to the point she was able to walk to the other room and call the emergency services. Upon arrival in the ED, she had mild deficits with minimal right facial droop and right arm pronator drift (NIHSS score 2). Her blood pressure was 165/95 mmHg. She underwent prompt CT of the head, which was negative for brain hemorrhage or space-occupying lesion. Upon re-examination following the scan, however, she was noted to have right hemiplegia and significant dysarthria (NIHSS score 12). Intravenous fluids were started and the physician discussed the risks and benefits of tPA with the patient, who agreed with proceeding. Approximately 10 minutes later, the nurse notified the physician that her weakness had improved such that her NIHSS score was now 6 (facial droop 2, dysarthria 1, 2-right arm 2, right leg 1). The physician cancelled the tPA order on the basis that the patient had made a “rapid improvement,” which disqualified her from thrombolysis. The patient remained stable in the ED but subsequently worsened on the ward with severe right hemiplegia again 12 hours after the initial onset. Imaging confirmed a left internal capsule infarct and work-up concluded that the mechanism was lacunar or small artery disease. She was discharged to acute inpatient rehabilitation with persistent right hemiplegia.

Discussion

Since its approval by the FDA in 1996, tPA use has been limited and even curtailed by misinterpretations of the many inclusion and exclusion criteria affixed to the drug label. Rapid improvement is one of the most common reasons for withholding thrombolysis in otherwise eligible patients [11]. The rationale for exclusion on this basis in the original trial was clear: to avoid treating patients with transient ischemic attack or non-disabling strokes (near complete or complete recovery) as they were expected to have excellent outcomes without treatment. However, substantial or dramatic improvement, rather than mild or moderate improvement, is required to satisfy this definition of rapid improvement and exclude a patient from thrombolysis. It should also be noted that early improvement often heralds subsequent deterioration [12], which has been speculated to be due to thrombus instability or collateral blood flow compromise. Patients with significant deficits despite moderate improvement, who are likely to be disabled at follow-up such as this patient, should be offered tPA.

The recent Re-examining Acute Eligibility for Thrombolysis (TREAT) taskforce unanimously recommended that patients with moderate–severe deficits who do not improve to non-disabling state should be offered IV tPA unless other contraindications are found [13]. Isolated symptoms such as moderate aphasia, hemianopsia, spatial neglect, and gait ataxia should be considered disabling and may justify thrombolysis. However, non-disabling deficits that should not be treated at this time pending ongoing trial evidence include isolated facial droop, non-dominant arm drift without hand weakness, hemisensory deficits without neglect, and isolated mild dysarthria (Table 7.1). Furthermore, it was advised that clinicians not delay tPA administration to allow for continued extended observation or monitoring.

Likely disabling | Likely non-disabling |

|---|---|

Cortically blind (NIHSS score 3) | Isolated facial droop |

Monoplegic or severely paretic arm or leg (NIHSS 2–4) | Mild hemimotor deficit (NIHSS score 2) |

Complete hemianopsia (NIHSS score 2) | Partial or mild hemianopsia (NIHSS score 1) |

Severe aphasia (NIHSS score 2) | Isolated mild aphasia (NIHSS score 1) |

Neglect (NIHSS score 1 or 2) | Hemisensory deficit (NIHSS 1 or 2) |

Gait or limb ataxia (NIHSS score 2) | Mild hemiataxia (NIHSS score 1) |

Dominant cortical hand (NIHSS score 0) | Non-dominant cortical hand without drift (NIHSS score 0) |

In patients who present with fluctuating lacunar stroke, the so-called capsular warning syndrome, wild fluctuations in severity have been known to occur, even within minutes. It is critical that such patients be carefully monitored for deterioration since the majority of such patients complete the stroke and are left with disabling deficits. It is imperative that treating physicians recognize that stroke patients will often fluctuate in the hyperacute setting, anticipate the potential for neurologic deterioration after initial improvement, and measure deficits for their impact on long-term disability when approaching thrombolysis decision-making.

Tip

Exclusion from thrombolysis by rapid improvement implies complete or near-complete recovery. It should not be applied in patients with mild or moderate fluctuations or improvements. Deferring treatment on the basis of mild or moderate improvement to a level that remains disabling is not advised given the likelihood of long-term disability. A suggested approach to determine whether symptoms may be disabling at the time of presentation is to consider whether the patient could perform basic activities of daily living (ADLs) and/or return to work. For example, a right-handed 55-year-old carpenter who has profound right-hand weakness without other deficits should be considered potentially disabled as it will likely impair performance of ADLs and recreational and vocational tasks.

Case 4. Misdiagnosis

Case description

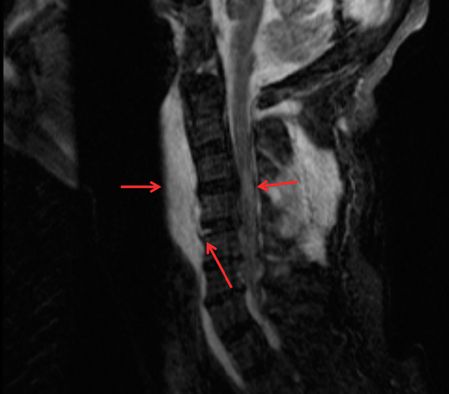

A 70-year-old Chinese man with hypertension was brought in by his son who found the patient on the floor in the kitchen of their apartment at 9 p.m. He was last seen normal at 8:45 p.m. following dinner. He was Cantonese speaking only, appeared confused, and was unable to provide details of history. He was not moving his left arm and leg as briskly as the right side but had no facial droop. There was no gaze deviation, sensory loss, visual field cut, or neglect. His blood pressure initially was 100/70 mmHg. CT head showed no signs of intracranial hemorrhage or skull fracture though a small hematoma was noted beneath his scalp. Given the possible stroke diagnosis and since he was within the 3-hour window, the neurology-on-call physician decided to treat with IV tPA. Three hours later, the patient developed some minor expansion of the left frontal subcutaneous hematoma requiring compression and also minor tongue and mouth bleeding but his exam remained unchanged with left-sided weakness and ataxia. The following morning, examination revealed he now had bilateral moderate arm and leg weakness, sensory changes to pinprick to the C7 level, and urinary retention. An emergent MRI of the brain and spine demonstrated mid-lower cervical cord edema along with ligamentous injury and paravertebral swelling at the same level secondary to acute trauma (Figure 7.2); no acute stroke was seen on brain imaging. Neurosurgery was consulted, tPA was reversed with cryoprecipitate, and he was taken to the operating room for spinal stabilization. Postoperatively, he continued to have mild to moderate quadriparesis and was ultimately discharged to an acute inpatient rehabilitation facility. Subsequent interviews with family informed the treating team that he regularly consumed large amounts of alcohol after dinner and that he was likely intoxicated leading to a mechanical fall in the kitchen.

MRI cervical spine showing pre-vertebral soft tissue edema, C5–6 level ligamentous tear, and central cord edema (arrows).

Discussion

In this patient, an unwitnessed mechanical fall occurred leading to initial hemi-cord symptoms of arm and leg weakness. Recent intracranial or intraspinal trauma is considered a contraindication to thrombolysis [14]. However, initial survey was negative for these major findings. Limited history and language barriers in the hyperacute setting further confused this situation as details of the onset of the symptoms were not assessed. Nevertheless, all efforts should be made to acquire pertinent historical details that would inform diagnosis and potentially important contraindications to thrombolysis. In this case, the absence of facial droop, the presence of mild (though at the time clinically ignored) weakness and ataxia on the right side, external trauma to the scalp, and relative hypotension should have alerted the neurologist to the possibility of mechanical fall leading to spinal cord injury.

The importance of reducing time to thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke treatment is well-established [15] and the success of national quality initiatives to reduce door-to-needle (DTN) time has recently been demonstrated [16]. A potential unintended consequence of rapid thrombolysis is administration of tPA to non-vascular conditions that simulate stroke. While treatment of stroke mimics with IV tPA appears to have a low risk of complication [17], rare and serious complications could result in significant harm to patients without stroke [18].

This case provides a cautionary example of real harm that occurred as a result of initial diagnostic error that led to inappropriate thrombolytic decision-making. Given the emphasis on rapid diagnosis of stroke that relies completely on clinical skills of history and examination and does not provide the luxury of confirmatory tests that would force time delays, neurological examination and careful screening for potential harmful contraindications and stroke mimics is more relevant than ever before. While bedside tools to increase diagnostic certainty of stroke have been posited [19], no one score or finding can supplant clinical intuition, experience, and judgment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree