Figure 12.1 Testing for afferent and efferent pupillary disorders

A.normal: both pupils constricted

B.efferent defect: shine torch in affected eye (dilated pupil): light is perceived but affected pupil is unable to react because of a defect in the efferent pathway. Because the afferent pathway is unaffected, there is a normal consensual response in the other eye

C.afferent defect: shine torch in affected eye (dilated pupil); light is not perceived and affected pupil in unable to react because of a defect in the afferent pathway. Because the afferent pathway is affected, there is no consensual response in the other eye

Pathway for pupillary dilatation (sympathetic)

The sympathetic fibres descend on the same side from the hypothalamus via the lateral brain stem to the cervical spinal cord leaving the cord anteriorly at C8, T1. The fibres then ascend on the same side in the sympathetic chain to the superior cervical ganglion and from there on the outside of the wall of the internal carotid artery to the ciliary ganglion and the dilator pupillae in the iris. A lesion anywhere along its path results in a constricted, small pupil (miosis). Because sympathetic nerves also supply fibres to the ipsilateral eyelid (levator palpebrae superioris), the orbit and adjacent skin, a lesion in the sympathetic chain also results in ptosis, enopthalmos and anhydrosis. The presence of all four signs together is called Horner’s syndrome, (Table 12.1).

Table 12.1 Characteristics of main pupillary disorders

| Disorder/site | Neurological findings | Main Causes |

| Optic neuritis (optic nerve, afferent) | pupils dilated, (afferent pupil defect) | inflammatory, infections, nutritional (vit B def), konzo, TAN* toxic (alcohol, drugs) |

| Third nerve palsy (parasympathetic, efferent) compression non compression | pupil dilated, (efferent pupil defect) ptosis (partial or full), eye in down and out position, paralysis of adduction & up/down movements pupil not dilated, otherwise the same as in compressive lesions | ↑ICP, SOL, aneurysm, cavernous sinus thrombosis diabetes, meningitis |

| Horner’s syndrome (sympathetic fibres) | ptosis (mild), miosis (pupil < other pupil), enopthalmos (eye less protruding), loss of sweating (may be absent) | cluster headache, apical lung tumours, cervical cord/brain stem lesions, dissecting aneurysms of carotid arteries |

| Holmes-Adie pupil (iris) | pupil(s) dilated, impaired to light (reacts slowly to near light) | variant of normal, autoimmune |

| Argyll-Robertson pupil (frontal lobe) | both pupils small & irregular, accommodate but no reaction to light | syphilis & diabetes |

* tropical ataxic neuropathy

Swinging torch test

A relative afferent pupil defect is a sign of optic neuritis in the eye being examined. It can be demonstrated by the swinging torch test, during which light is repeatedly shone alternatively into the good eye and the affected eye. When light is shone on the non affected good eye, both pupils constrict normally, however, when the light is transferred briskly to the affected or bad eye both pupils dilate (Fig. 12.2). The explanation for this is that the weak direct effect on the bad eye is counterbalanced by the withdrawal of the stimulus from the good eye and the loss of the consensual response. This is a sign of incomplete optic neuropathy and is most commonly seen in optic neuritis.

Figure 12.2 Testing for a relative afferent pupillary defect.

A.Both pupils constrict on shining light in unaffected left eye

B.Both pupils dilate on shining light in affected right eye (relative afferent pupillary defect)

THE ACCOMMODATION REFLEX

When using near vision the eyes converge and pupils constrict, this is the accommodation reflex. The afferent component of the accommodation reflex is conveyed in the optic nerve and the efferent pathway is less certain but does involve the visual cortex and some of the same pathways as the efferent light reflex. Testing for the presence of the accommodation reflex has become less useful in clinical practice especially with the decrease in the frequency of neurosyphilis worldwide (Chapter 6).

PUPILLARY DISORDERS

Disorders affecting pupils occur at four main sites; the eye, the afferent or optic pathway, the efferent or parasympathetic pathway and the sympathetic pathway (Table 12.1). The main disorders affecting the eye include infection, inflammation and trauma.

Neurological disorders affecting the afferent pathway are relatively common in Africa. These are termed optic neuropathies and result in loss of vision and afferent pupil defects (Fig 12.1C). The main causes are inflammatory (optic neuritis), nutritional and toxic. However, in many cases their cause is unknown.

Disorders affecting the efferent pathway (Fig 12.1B) also occur. If the oculomotor (3rd nerve) is compressed on its path from the brain stem to the eye, then damage to the parasympathetic fibres which travel on the outside will result in a fixed, dilated pupil on that side. There may also be features of 3rd nerve palsy depending on the extent of the compression. Important neurological causes include raised intracranial pressure above the tentorium and an aneurysm compressing the nerve.

Disorders affecting the sympathetic pathway can occur anywhere along its pathway from the lateral brainstem to the eye, resulting in Horner’s syndrome. A small constricted pupil and slight ptosis are characteristic. Neurological causes are uncommon and mainly involve lesions in its central pathway. Primary lung cancer involving the apex of the lung is an important cause, although this disorder is still relatively uncommon in Africa.

Other disorders affecting pupils include the Holmes Adie pupil which is a benign condition usually affecting one side which is found in women in their 20-40s. The affected pupil is dilated with an impaired response to light but also accommodates slowly. It may be or becomes bilateral and is also associated with absent ankle reflexes (Table 12.1). The Argyll-Robertson pupil is a small and irregular pupil that accommodates to near vision but has a reduced or absent light reflex (Table 12.1). It was a well known sign of neurosyphilis but is very uncommon in clinical practice nowadays.

Key points

- pupillary disorders can arise from disorders of the eye, optic, parasympathetic & sympathetic nerves

- commonly found in association with disorders of eyelid (Horner’s) and eye movements (3rd N. palsy)

- afferent disorders (optic nerve) are mainly caused by inflammation & toxicity

- efferent disorder (parasympathic) is mainly caused by pressure from the outside on the 3rd nerve

- Horner’s syndrome is caused by local compression along the sympathetic nerve pathway

VISUAL ACUITY (VA)

VA is tested using a Snellen chart and the result is expressed as a fraction; the numerator being the distance between the chart and the patient (usually 6 metres depending on the size of the chart) divided by the denominator which is the smallest full line of letters identified correctly by the patient (Chapter 1). 6/6 is normal vision whereas 6/60 represents poor VA, meaning the patient can only read the largest letter on the chart. If the largest letter cannot be read from a distance of 6 metres, then the chart should be brought closer to the patient and VA rechecked. If this still fails, then the patient’s ability to correctly count fingers, identify hand movements or perceive light should be checked in each eye respectively. Remember to check patients VA wearing glasses (if the patient uses them) and recheck decreased VA with a pin hole to exclude cataracts and refractive errors as a likely cause. Illustrative charts are available for illiterate patients and hand held reading charts can be used to formally test near vision. Identifying the various sizes of letters from a local newspaper can suffice for a general impression of VA. The main causes of decreased VA are ocular. These include refractive errors in the lens, cataracts and retinal diseases, particularly of the macula. The main neurological causes are disorders affecting the optic nerve.

Key points

- first ask if the patient can see, using both eyes or with glasses

- test VA in each eye separately using a Snellen chart or a hand held chart or a newspaper

- if pt is still unable to read large letters check VA by counting fingers, hand movements & light perception

- commonest causes of decreased VA are refractive lens errors & cataracts

- most frequent neurological cause of decreased VA is optic neuropathy

Colour vision

Colour vision is not routinely tested but can be tested using a set of Ishihara colour plates. These consist of a series of plates of coloured dots arranged so that persons with normal colour vision can see and identify correctly, a hidden set of numbers or trails arranged in different colours on each plate of dots. The patient must be able to read the first (control) plate before proceeding and each eye should be tested separately. Defective colour vision may be inherited and is a feature of diseases involving the optic nerve in particular optic neuritis.

VISUAL FIELDS

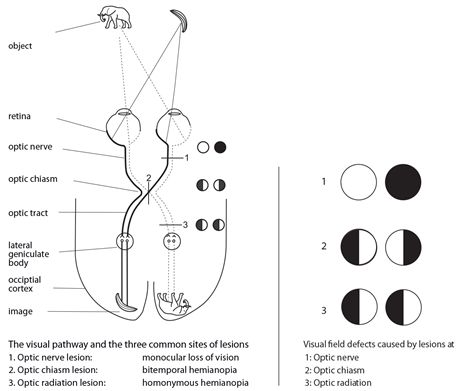

Patient’s visual fields are tested by confrontation. The confrontation method is useful for detecting large visual field defects in the visual pathway. In order to interpret and localize the main findings correctly it is important to remember the following three points. The nasal side of each eye picks up the opposite or temporal half of the visual field whilst the temporal side of the eye picks up the opposite or nasal half of the visual field (Fig. 12.3). The optic nerve fibres serving the nasal sides of the retina decussate to the opposite side at the level of the optic chiasm (Fig. 12.3). Finally by convention the patient’s visual fields are always described and illustrated from the patient’s own perspective i.e. as if the patient were looking outwards (Fig. 12.4). The main visual defects, their sites of origin and causes are outlined below (Table 12.2).

Table 12.2 Visual field defects, sites & causes

| Field defect | Site | Main causes |

| 1. monocular | optic nerve | neuritis, vasculitis, compressive: aneurysm, meningioma |

| 2. bitemporal hemianopia | optic chiasm | pituitary adenoma, craniopharyngioma |

| 3. homonymous hemianopia | optic tract/occipital lobe | stroke, SOL, tumour |

Key points

- check for visual field defects in both eyes by confrontation

- if defect is suspected, then test each eye individually

- define the limits or extent of any field defect found

- main sites of origin of visual field defects are optic nerve, chiasm & optic tract/radiation

- most common defect is homonymous hemianopia secondary to a stroke/SOL

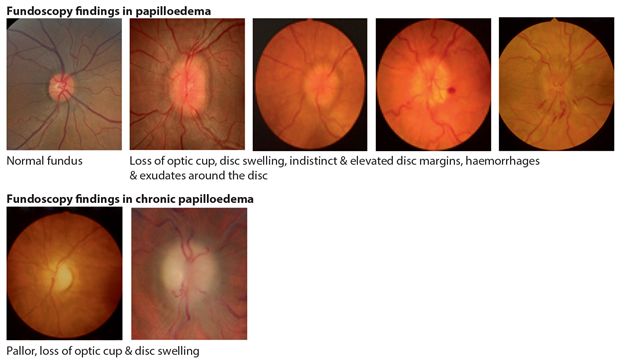

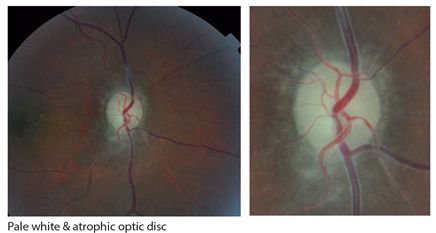

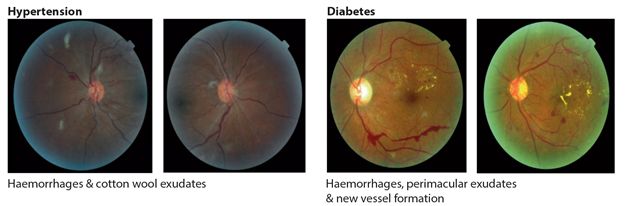

FUNDOSCOPY

The technique and details of fundoscopy are described in Chapter 1. In summary, it is important to look at and inspect the optic disc, blood vessels and retinal background. An example of a normal fundus is shown in fig 12.5. Disorders affecting the optic nerves may result in swelling of the optic disc, called papilloedema or wasting of the optic nerve called optic atrophy. Both of these disorders can be easily seen and identified by fundoscopy and are illustrated below (Figs 12.5 & 6). Examples of retinopathy in hypertension and diabetes are included for comparison (Fig 12.7).

Figure 12.5 Fundoscopy findings in papilloedema

Figure 12.6 Fundoscopy findings in optic atrophy

Figure 12.7 Fundoscopy findings in hypertension and diabetes

Papilloedema

Papilloedema is swelling of the optic disc sometimes with surrounding retinal haemorrhages and exudates. It is nearly always caused by raised intracranial pressure but it may also be due to inflammation of the optic nerves when it is termed optic neuritis or papillitis. Papilloedema is nearly always bilateral and occurs mostly without visual symptoms. On examination VA is typically normal but the blind spot may be enlarged and the peripheral visual fields constricted. Fundoscopy confirms features of papilloedema, a swollen and sometimes haemorrhagic disc (Fig. 12.5). If the papilloedema is long standing, then VA is lost due to increased pressure around the optic nerve and the optic disc becomes atrophied and pale. The main cause of papilloedema in Africa is raised intracranial pressure secondary to either infections, (cryptococcal and TB meningitis), space occupying lesions (SOL) or malignant hypertension (Table 12.3).

Table 12.3 Main causes of papilloedema

| Disorder | Disease |

| raised intracranial pressure | cryptococcus/TB, malignant hypertension, SOL |

| optic nerve lesions | tumours, leukaemia, Drusen |

| inflammatory | Devic’s disease |

Optic neuritis

Optic neuritis is inflammation of the optic nerve or nerve head. It is usually bilateral but may occasionally be unilateral. It presents with loss of vision and occasionally a dull ache behind the eyes. On examination, VA is decreased or lost and there may be afferent pupil defects, if both eyes are involved. Fundoscopy may show papilloedema in the acute stage; however the accompanying loss of VA suggests optic neuritis rather than papilloedema as the true cause. In long standing cases there is optic atrophy (Fig. 12.6). The main disorders causing optic neuritis are inflammatory, toxic, nutritional and infections (Table 12.4).

Table 12.4 Main causes of optic atrophy

| Disorder | Disease |

| chronic raised intracranial pressure | any cause |

| post infectious | TB, syphilis, viral |

| post inflammatory | Devic’s disease, autoimmune disorders |

| toxic | alcohol, methanol, isoniazid, ethambutol, quinine |

| nutritional | Konzo, TAN*, Vitamin B deficiency |

| vascular | ischaemia |

| hereditary | Leber’s optic neuropathy |

* tropical ataxic neuropathy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree