Cranial Nerves IX and X (The Glossopharyngeal and Vagus Nerves)

Anatomy of Cranial Nerve IX (Glossopharyngeal Nerve)

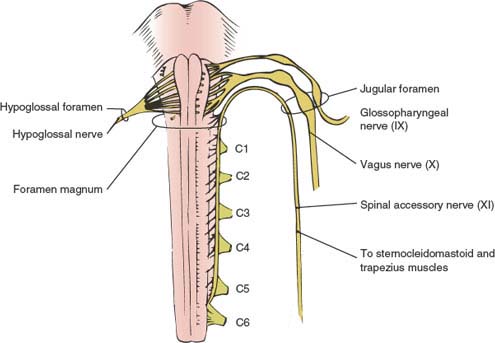

The glossopharyngeal nerve contains motor, sensory, and parasympathetic fibers. The nerve emerges from the posterior lateral sulcus of the medulla oblongata dorsal to the inferior olive in close relation with cranial nerve X (the vagus nerve) and the bulbar fibers of cranial nerve XI (the spinal accessory nerve) (Fig. 12.1) [6,31]. These three nerves then travel together through the jugular foramen. Within or distal to this foramen, the glossopharyngeal nerve widens at the superior and the petrous ganglia and then descends on the lateral side of the pharynx, passing between the internal carotid artery and the internal jugular vein. The nerve winds around the lower border of the stylopharyngeus muscle (which it supplies) and then penetrates the pharyngeal constrictor muscles to reach the base of the tongue.

The motor fibers originate from the rostral nucleus ambiguus and innervate the stylopharyngeus muscle (a pharyngeal elevator) and (with the vagus nerve) the constrictor muscles of the pharynx.

The sensory fibers carried in the glossopharyngeal nerve include taste afferents, supplying the posterior third of the tongue and the pharynx, and general visceral afferents from the posterior third of the tongue, tonsillary region, posterior palatal arch, soft palate, nasopharynx, and tragus of the ear. By way of the tympanic branch of the glossopharyngeal nerve (Jacobson’s nerve), sensation is supplied to the tympanic membrane, eustachian tube, and the mastoid region. Taste afferents and general visceral afferent fibers have their cell bodies in the petrous ganglion and terminate mainly in the nucleus of the solitary tract (the rostral terminating fibers convey taste, and the caudal terminating fibers convey general visceral sensation); exteroceptive afferents have their cell bodies in the superior and petrous ganglia and terminate in the spinal nucleus of the trigeminal nerve. The glossopharyngeal nerve also carries chemoreceptive and baroreceptive afferents from the carotid body (chemoreceptors) and carotid sinus (baroreceptors), respectively, by way of the carotid sinus nerve (nerve of Hering).

The parasympathetic fibers carried in the glossopharyngeal nerve originate in the inferior salivatory nucleus, located in the periventricular gray matter of the rostral medulla, at the superior pole of the rostral nucleus of cranial nerve X. These parasympathetic preganglionic fibers leave the glossopharyngeal nerve at the petrous ganglion and travel by way of the tympanic nerve or Jacobson’s nerve (coursing in the petrous bone) and the lesser superficial petrosal nerve to reach the otic ganglion (just below the foramen ovale), where they synapse. The postganglionic fibers then travel by way of the auriculotemporal branch of the trigeminal nerve, carrying secretory and vasodilatory fibers to the parotid gland.

Clinical Evaluation of Cranial Nerve IX

Motor Function

Stylopharyngeal function is difficult to assess. Motor paresis may be negligible with glossopharyngeal nerve lesions, although mild dysphagia may occur and the palatal arch may be somewhat lower at rest on the side of glossopharyngeal injury. (However, the palate elevates symmetrically with vocalization.)

Sensory Function

The integrity of taste sensation may be tested over the posterior third of the tongue and is lost ipsilaterally with nerve lesions. Sensation (pain, soft touch) is tested on the soft palate, posterior third of the tongue, tonsillary regions, and pharyngeal wall. These areas may be ipsilaterally anesthetic with glossopharyngeal lesions.

Reflex Function

The pharyngeal or gag reflex is tested by stimulating the posterior pharyngeal wall, tonsillar area, or base of the tongue. The response is tongue retraction associated with elevation and constriction of the pharyngeal musculature. The palatal reflex consists of elevation of the soft palate and ipsilateral deviation of the uvula with stimulation of the soft palate. The afferent arcs of these reflexes probably involve the glossopharyngeal nerve, whereas the efferent arcs involve both the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves. Unilateral absence of these reflexes is seen with glossopharyngeal nerve lesions.

FIG. 12.1. Ventral view of medulla and cranial nerves IX, X, and XI exiting together through the jugular foramen. Dorsal roots of C1 through C6 in the upper cervical spinal cord are also shown. (From Daube JR, Reagan TJ, Sandok BA. Medical neurosciences: an approach to anatomy, pathology, and physiology by system and levels, 2nd ed. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1986. By permission of Mayo Foundation.)

Autonomic Function

Salivary secretion (from the parotid gland) may be decreased, absent, or occasionally increased with glossopharyngeal lesions, but these changes are difficult to demonstrate without specialized quantitative studies.

Localization of Lesions Affecting the Glossopharyngeal Nerve

Lesions affecting the glossopharyngeal nerve also usually involve the vagus and therefore syndromes affecting both nerves are much more common than nerve lesions occurring in relative isolation.

Supranuclear Lesions

Supranuclear lesions, if unilateral, do not result in any neurologic deficit because of bilateral corticobulbar input to the nucleus ambiguus. However, bilateral corticobulbar lesions (pseudo-bulbar palsy) result in severe dysphagia [16] along with other pseudo-bulbar signs (e.g., pathologic laughter and crying, spastic tongue, explosive spastic dysarthria). With stimulation, the gag reflex may be depressed or markedly exaggerated, resulting in severe retching and even vomiting.

Nuclear and Intramedullary Lesions

These lesions include syringobulbia, demyelinating disease, vascular disease, motor neuron disease, and malignancy. Such lesions commonly involve other cranial nerves, especially the vagus, and other brainstem structures (e.g., Wallenberg syndrome) and are therefore localized by “the company they keep.”

Extramedullary Lesions

CEREBELLOPONTINE ANGLE SYNDROME

The glossopharyngeal nerve may be injured by lesions, especially acoustic tumors, occurring in the cerebellopontine angle. Here there may be glossopharyngeal involvement associated with tinnitus, deafness, and vertigo (cranial nerve VIII), facial sensory abnormalities (cranial nerve V), and occasionally other cranial nerve or cerebellar involvement.

JUGULAR FORAMEN SYNDROME (VERNET’S SYNDROME)

Lesions at the jugular foramen, especially glomus jugulare tumors and basal skull fractures, injure cranial nerves IX, X, and XI, which travel through this foramen. Other etiologies include neuroma, metastasis to the skull base, cholesteatoma, meningioma, infection, and giant cell arteritis [12]. Vernet’s syndrome consists of the following:

1. Ipsilateral trapezius and sternocleidomastoid paresis and atrophy (cranial nerve XI)

2. Dysphonia, dysphagia, depressed gag reflex, and palatal droop on the affected side associated with homolateral vocal cord paralysis, loss of taste on the posterior third of the tongue on the involved side, and anesthesia of the ipsilateral posterior third of the tongue, soft palate, uvula, pharynx, and larynx (cranial nerves IX and X)

3. Often dull, unilateral aching pain localized behind the ear

Occipital condylar fracture may cause paralysis of cranial nerves IX and X [36].

LESIONS WITHIN THE RETROPHARYNGEAL AND RETROPAROTID SPACE

The glossopharyngeal nerve may be injured in the retropharyngeal or retroparotid space by neoplasms (e.g., nasopharyngeal carcinoma), abscesses, adenopathy, aneurysms [35], trauma (e.g., birth injury [13]), or surgical procedures (e.g., carotid endarterectomy). Resulting syndromes include the Collet-Sicard syndrome (affecting cranial nerves IX, X, XI, and XII) and Villaret’s syndrome (affecting cranial nerves IX, X, XI, and XII, the sympathetic chain, and occasionally cranial nerve VII). The glossopharyngeal nerve may rarely be damaged in isolation by retropharyngeal or retroparotid space lesions resulting in a “pure” glossopharyngeal syndrome (mild dysphagia, depressed gag reflex, mild palatal droop, loss of taste on the posterior third of the tongue, glossopharyngeal distribution anesthesia). For example, traumatic internal maxillary artery dissection and pseudoaneurysm may present with isolated glossopharyngeal nerve palsy [1].

Glossopharyngeal (Vagoglossopharyngeal) Neuralgia

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia [5,8,32] refers to a unilateral pain (usually stabbing, sharp, and paroxysmal) located in the field of sensory distribution of the glossopharyngeal or vagus nerves. Patients usually describe an abrupt, severe pain in the throat or ear that lasts seconds to minutes and is often triggered by chewing, coughing, talking, yawning, swallowing, and eating certain foods (e.g., highly spiced foods). The pain may occasionally be more persistent and have a dull aching or burning quality. Other areas (e.g., larynx, tongue, tonsils, face, jaw) may also be affected.

The attacks of glossopharyngeal pain may occasionally be associated with coughing paroxysms, excessive salivation, hoarseness, and, rarely, syncope [10,32,39]. Occasionally, loss of awareness associated with clonic jerks of the extremities may occur [21]. The syncopal episodes may possibly result from reflex bradycardia and asystole due to stimulation of the tractus solitarius and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus by impulses originating in glossopharyngeal afferents.

Vagoglossopharyngeal neuralgia is often “idiopathic” and may be related to ephaptic excitation of the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves; however, lesions in the posterior fossa or anywhere along the peripheral distribution of the glossopharyngeal nerve (e.g., tumor, infection, trauma) may also cause the syndrome. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia was caused in one patient by compression of the lower cranial nerves and brainstem by the displaced left cerebellar tonsil with Chiari I malformation [20]. Multiple sclerosis is an extremely rare etiology for this syndrome [27] (unlike its relatively common association with trigeminal neuralgia).

Anatomy of Cranial Nerve X (Vagus Nerve)

The vagus nerve or pneumogastric nerve contains motor, sensory, and parasympathetic nerve fibers [6,31]. The six to eight rootlets of the vagus nerve emerge from the posterior sulcus of the lateral medulla oblongata dorsal to the inferior olive in close association with the glossopharyngeal nerve (Fig. 12.1). These vagal rootlets form a single trunk that leaves the skull by way of the jugular foramen in a dural sheath that also contains the spinal accessory nerve. Within, or just inferior to, the jugular foramen are the two vagal ganglia: the jugular (general somatic afferent) and the nodose (special and general visceral afferent). Between the two ganglia, the auricular ramus (nerve of Arnold) of the vagus nerve is given off; this branch then traverses the mastoid process and innervates the skin of the concha of the external ear. At this point the vagus also gives off the meningeal ramus, which runs to the dura mater of the posterior fossa, and the pharyngeal ramus, which forms the pharyngeal plexus with the glossopharyngeal nerve and sends motor fibers to the muscles of the pharynx and the soft palate (except the stylopharyngeus and tensor veli palatini muscles). The superior laryngeal nerve arises from the vagus near the nodose ganglion and divides into a predominantly motor external ramus (to the cricothyroid muscle) and an internal ramps (which pierces the thyrohyoid membrane and sends sensory fibers to the larynx).

In the neck, the vagus nerve proper descends within a sheath common to the internal carotid artery and the internal jugular vein. Within the neck, the vagus gives off the cardiac rami, which follow the carotid arteries down to the aorta and contribute fibers to the cardiac plexus. At the root of the neck, the recurrent laryngeal nerves are given off and pursue different courses on the two sides. The right recurrent laryngeal nerve bends upward behind the subclavian artery to ascend in the tracheoesophageal sulcus, whereas the left recurrent laryngeal nerve passes beneath the aortic arch to attain this sulcus. The recurrent laryngeal nerves then divide into anterior and posterior rami, which supply all of the muscles of the larynx except the cricothyroid muscle (supplied by the external ramus of the superior laryngeal nerve).

The vagus nerve enters the thorax, crossing over the subclavian artery on the right side and traveling between the left common carotid and subclavian arteries on the left side. The right nerve then passes downward near the brachiocephalic trunk and trachea and behind the right brachiocephalic vein and superior vena cava to the posterior lung root. The left nerve travels between the left common carotid and subclavian artery, passes over the aortic arch, and reaches the left lung root. In the posterior mediastinum both nerves send fibers to the pulmonary and esophageal plexuses and then enter the abdomen by way of the esophageal opening of the diaphragm (the left nerve in front of the esophagus, the right nerve behind it). The vagi terminate by innervating the abdominal viscera.

The motor fibers carried in the vagus nerve arise from the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus and the nucleus ambiguus. The dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus is situated on the floor of the fourth ventricle lateral to the hypoglossal nucleus. This nucleus gives rise to preganglionic parasympathetic fibers that innervate the pharynx, esophagus, trachea, bronchi, lungs, heart, stomach, small intestine, ascending and transverse colon, liver, and pancreas. The nucleus ambiguus is located in the reticular formation of the medulla medial to the spinal tract and nucleus of the trigeminal nerve. Fibers from this nucleus supply all of the striated musculature of the soft palate, pharynx, and larynx except the tensor veli palatini (cranial nerve V) and stylopharyngeus (cranial nerve IX) muscles. The cortical centers for control of vagal motor function are located in the lower precentral gyri, with supranuclear innervation predominantly crossed but bilateral.

The sensory fibers carried in the vagus nerve have their perikarya in the jugular and nodose ganglia. Within the nodose ganglion are cells whose fibers carry taste sensation from the epiglottis, hard and soft palates, and pharynx. The axons of these ganglion cells terminate in the nucleus solitarius of the medulla. General visceral sensations from the oropharynx, larynx, and linings of the thoracic and abdominal viscera have their cells of origin in the nodose ganglion, which also projects to the nucleus solitaries (nucleus parasolitarius). Exteroceptive sensation from the concha of the ear is carried by the vagus (jugular ganglion) to terminate in the descending (spinal) nucleus of the trigeminal nerve.

Clinical Evaluation of Cranial Nerve X

Motor Function

The striated muscles of the soft palate (except the tensor veli palatini), pharynx, and larynx are innervated by the vagus nerve. The soft palate and uvula are examined at rest and with phonation; with phonation, the palate should elevate symmetrically with no uvular deviation. Pharyngeal function is evaluated by observing pharyngeal contraction during phonation and swallowing and by noting the character of the voice, by noting the ease of respirations and cough, and by direct observation of laryngeal movements during laryngoscopy.

With unilateral vagal lesions, there is ipsilateral flattening of the palatal arch; with phonation, the ipsilateral palate fails to elevate, and the uvula is retracted toward the nonparalyzed side. Dysphagia and articulation disturbances (a “nasal twang” to the voice) may occur, and during phonation only the upper pharynx is elevated. The ipsilateral vocal cord assumes the cadaveric position (midway between adduction and abduction), and although voluntary coughing may be impaired, there is little dyspnea.

With bilateral vagal lesions, the palate droops bilaterally with no palatal movement, on phonation. On speaking, air escapes from the oral to the nasal cavity, giving the voice a “nasal” quality. Bilateral pharyngeal involvement results in profound dysphagia, more pronounced for liquids, which tend to be diverted into the nasal cavity. The voice is hoarse and weak, coughing is poor or not possible, and respiration is severely embarrassed.

Sensory Function

Sensory function of the vagus nerve cannot be tested adequately because the area of supply overlaps that of other cranial nerves (e.g., the pinna), some structures are inaccessible (e.g., the meninges), and there is difficulty in testing the epiglottis for taste function.

Reflex Function

The afferent limb of the pharyngeal reflex (gag reflex) runs in the glossopharyngeal nerve, and the efferent limb runs in the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves. Therefore, unilateral vagal lesions depress the ipsilateral gag reflex by interrupting the efferent arc.

Localization of Lesions Affecting the Vagus Nerve

Supranuclear Lesions

Unilateral cerebral hemispheric lesions (lower precentral gyrus) rarely cause any vagal dysfunction because the supranuclear control is bilateral. Rarely, dysphagia may occur with a unilateral precentral lesion [26]. Unilateral palatal paralysis without notable weakness of the extremities has been described with a cerebral infarct affecting the superior segment of the corona radiata [18]. The site of the lesion corresponded to the corticofugal motor tract from the motor cortex to the genu of the internal capsule.

Bilateral upper motor neuron lesions result in pseudo-bulbar palsy, in which dysphagia and spastic dysarthria are prominent. Emotional incontinence with pathologic crying is common. The gag reflex may be depressed or exaggerated.

Nuclear Lesions and Lesions Within the Brainstem

Lesions of the nucleus ambiguus may occur with vascular insults (lateral medullary or Wallenberg syndrome), tumors, syringobulbia, motor neuron disease, and inflammatory disease. Nuclear lesions result in ipsilateral palatal, pharyngeal, and laryngeal paralysis that is usually associated with affection of other cranial nerve nuclei, roots, and long tracts. When only the more cephalad portion of the nucleus ambiguus is injured, laryngeal function is spared (palatopharyngeal paralysis of Avellis) owing to the somatotopic organization of this motor nucleus. Vocal cord dysfunction (hoarseness, hypophonia, and short phonation time, nocturnal nonproductive cough, and attacks of inspiratory stridor due to laryngeal spasm, choking, and paroxysmal dyspnea) occurs rarely with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [38].

Lesions within the Posterior Fossa

The vagus nerve may also be damaged where it emerges from the medulla. Lesions at this location usually also involve the glossopharyngeal, spinal accessory, and hypoglossal nerves and include primary (e.g., glomus jugulare) and metastatic tumors, infections (e.g., meningitis, otitis), carcinomatous meningitis, sarcoidosis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, and trauma. The syndromes that occur most commonly include the following: