22 Deformity

I. Key Points

– The scoliotic spine has, in addition to a coronal curve, a rotational deformity in which the apical vertebra rotates. The three-dimensional nature of the disease process must be taken into account in planning surgery.

– A magnetic resonance image (MRI) should be obtained in the workup of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis when there are neurologic abnormalities, midline cutaneous findings, a left thoracic curve, rapid curve progression, or a hyperkyphotic thoracic alignment.

– In planning surgery for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, all major curves and structural minor curves should be included in the fusion levels.1

– In younger patients treated with posterior-only fusion, subsequent growth anteriorly can create a crankshaft phenomenon.

– Scheuermann kyphosis must be differentiated from postural kyphosis, which reduces on hyperextension lateral radiographs. Additionally, postural kyphosis does not exhibit the accentuated hump on the Adam forward bending test that is seen with Scheuermann kyphosis.

II. Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis

– Background

• Scoliosis is defined as an abnormal curvature of the spine in the coronal plane greater than 10 degrees.

• Etiologies include idiopathic, which makes up 80% of all cases, as well as congenital, neuromuscular, and syndrome-related.

• Idiopathic scoliosis is classified based on age at diagnosis: infantile, 0 to 3 years; juvenile, 4 to 10 years; adolescent, 11 to 17 years; and adult, 18 years and older.

• Curves may be classified as major or minor. The major curve is of the greatest magnitude and is considered the first to develop (Fig. 22.1).1

• Minor, or compensatory, curves develop later and basically serve to balance the head and trunk over the pelvis.

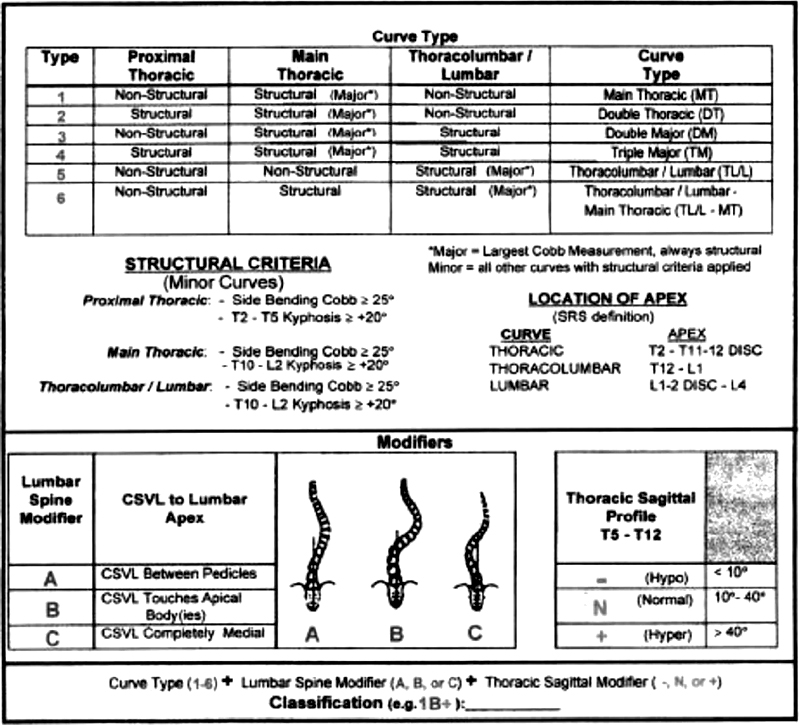

Fig 22.1 Developed in 2001, the Lenke classification provides treatment recommendations for various AIS deformities. Major and structural minor curves are included in the instrumented fusion and the nonstructural curves are excluded. (From Clements DH et al. “Did the Lenke Classification Change Scoliosis Treatment?” Spine 36(14):1142–1145.)

• Structural curves are rigid and cannot be corrected to less than 25 degrees with lateral bending. Nonstructural curves are less rigid and can be corrected.1

• The normal spine has a thoracic kyphosis between 20 and 40 degrees and a lumbar lordosis between 40 and 70 degrees, and is straight in the coronal plane without rotation.

• The scoliotic spine not only has a coronal curve, but also has a rotational deformity where the apical vertebra rotates. Most progressive AIS is convex right in the thoracic spine. Any left thoracic curve should be worked up with MRI for underlying abnormalities.

• Scoliosis causes changes in the physiology of the discs and vertebrae due to compressive forces on the concave side of the curve. Increased pressure reduces growth, causes wedging of discs, and changes the remodeling of the bone. All this contributes to continued asymmetric growth, worsens the deformity, and perpetuates the process.

– Signs, symptoms, and physical exam

• The physician should include questions about the patient’s recent growth, physical signs of puberty, onset of menses, and axillary/pubic hair.

• Family history of scoliosis should be obtained.

• A thorough review of systems can shed light on other conditions associated with scoliosis.

• Important findings in the history include severe back pain, presence of neurologic symptoms, age at onset of scoliosis, and rate of progression.

• Severe back pain with radicular or myelopathic symptoms requires further imaging with MRI to rule out any specific underlying etiology such as syringomyelia, Chiari malformation, tethered cord, diastematomyelia, or intraspinal tumors.

• Neurologic history should include questions about difficulties with writing, grasping, balance, walking, or climbing stairs; loss of bowel or bladder function; weakness; or numbness and tingling.

• Trunk shape and balance should be assessed. The posterior torso should be examined with the patient standing. Look for shoulder, trapezial, scapular, and trunk or flank asymmetry.

• A plumb line dropped from the C7 spinous process should fall in line with the gluteal cleft.

• The lateral aspects of the rib cage should be aligned with the ipsilateral iliac crest. Often patients perceive a curve in the spine as a hip or pelvis problem.

• The Adam forward bending test should be performed. With the knees straight and palms together, the patient is asked to bend forward at the waist. The examiner observes the patient from behind to assess lumbar and midthoracic rotation, from the front to assess upper thoracic rotation, and from the side to assess kyphosis.

• A scoliometer may be used to measure the angle of trunk rotation (ATR). An ATR of 5 to 7 degrees is associated with a Cobb angle of 15 to 20. The rib hump deformity can also be measured in centimeters.

• Pelvic tilt due to leg length inequality can be assessed by examining the patient from behind and placing blocks under the short leg to equalize the lengths.

• Skin should be inspected for abnormalities such as café-aulait spots or axillary freckling, both associated with neurofibromatosis. Dimpling of the skin, hair tufts, or any midline cutaneous abnormality may indicate spina bifida and should be further explored. In addition, any skin laxity may indicate Marfan or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

• The neurologic exam should include assessment of the patient’s balance, sensation, and motor strength. Patient’s gait and ability to heel-toe walk should be assessed. Abdominal reflexes, deep tendon reflexes, Hoffman and Babinski signs, and clonus should all be included in the test.

– Neuroimaging

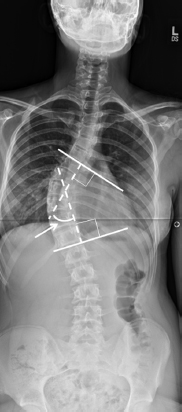

• Standing posteroanterior (PA) plain radiographs of the entire spine down to the pelvis on a single 3-foot cassette should be obtained. Skeletal maturity can be assessed based on the iliac apophysis (Risser method). The Cobb angle measures the coronal plane curvature and is determined by the angle between the line parallel to the superior end plate of the most tilted cephalad vertebra and the line parallel to the inferior end plate of the most tilted caudal vertebra (Fig. 22.2).

Fig. 22.2 A full-length standing PA radiograph of a 16-year-old female with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. This patient has a right thoracic curve. The Cobb method of curve measurement is depicted. To perform a Cobb measurement, lines are first drawn parallel to the superior end plate of the most tilted cephalad vertebra and the inferior end plate of the most tilted caudal vertebra. Lines are then drawn perpendicular to the end plate lines. The angle between these perpendicular lines is the Cobb angle.

• Full-length standing lateral plain radiographs are obtained at initial screening if there is back pain, or if there is an obvious sagittal or coronal deformity. Also, lateral lumbar films are obtained to evaluate for spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis.

• PA bending plain radiographs are obtained when surgery is being contemplated. Bending films assess the flexibility of the curve(s) and aid in operative planning. Again, if a curve corrects to less than 25 degrees with lateral bending, it is considered non-structural.

• MRI is not routinely obtained in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS). Neurologic abnormalities, midline cutaneous findings, left thoracic curves, rapid curve progression, or hyperkyphotic thoracic alignment warrants MRI.

– Treatment

• Curves less than 20 degrees should be monitored with radiographs and clinical exam every 6 to 12 months. Patients growing rapidly should be seen more frequently.

• Curves 20 to 40 degrees are generally treated with a brace. The effectiveness of bracing depends on the remaining spinal growth. The Milwaukee brace has fallen out of favor (because of the neck piece) and has given way to the more cosmetically favorable and comfortable underarm braces like the Boston and Wilmington braces. These should be worn full-time (23 hours a day). The Charleston brace is worn only at night.

• Patients with curves that progress to 45 to 50 degrees are usually candidates for surgery. Factors to consider include clinical deformity, risk of progression, level of skeletal maturity, and pattern of curve.2

• According to Lenke and colleagues, all major curves and structural minor curves should be included in the fusion levels.1

• Posterior spinal fusion using instrumentation such as hooks, pedicle screws, wires, or hybrid constructs is the mainstay of surgical correction. Pedicle screws give an ability to apply three-dimensional corrective forces that hooks cannot.

• Complications of operative treatment include neurologic injury, blood loss, and implant failure. Spinal cord monitoring is routinely used to decrease the risk of neurologic injury.

• In younger patients treated with posterior-only fusion, subsequent growth anteriorly can create a crankshaft phenomenon.

– Surgical pearls

• Large curves that measure over 70 degrees may be rigid and technically difficult to correct. Combined anterior and posterior fusion has been recommended by some surgeons. Removing the disc and releasing the anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL) anteriorly allows increased flexibility of the curve along with greater curve correction, and enables the surgeon to fuse the anterior vertebral column, minimizing the risk of developing a crankshaft phenomenon.

III. Scheuermann Kyphosis

– Background

• Originally described by Holger Werfel Scheuermann, this is a rigid sagittal deformity of the thoracic spine that cannot be actively corrected.3

• The vertebral bodies are wedged anteriorly at three consecutive levels.

• There are three types of Scheuermann kyphosis (SK). Type I is the classic deformity with the apex between T7 and T9; type II is thoracolumbar in nature, with the apex between T10 and T12; and type III is a lumbar lordosis.

• The etiology of SK remains unknown; however, several theories have been proposed, including an avascular necrosis of the vertebral ring apophysis, end plate deterioration and collapse as a result of the herniation of disk material into the vertebra, simple wedging caused by mechanical forces, and endocrine and genetic factors.4

• Histology studies have revealed significant end plate irregularities, including Schmorl nodes, which are essentially disk herniations into the vertebral body.

– Signs, symptoms, and physical exam

• SK is typically idiopathic in nature but can be associated with Turner syndrome and cystic fibrosis.

• A complete history and physical exam are important to distinguish SK from postural kyphosis.

• The typical patient presents around puberty and relays a history of a progressive thoracic kyphosis. Often a compensatory lumbar lordosis can be appreciated on exam. Hamstring tightness is often found.5

• Patients may have pain at the apex of the curvature. Pain is more common in athletes.

• A complete physical exam noting the sagittal and coronal alignment is important.

• Often a compensatory lumbar lordosis can be established. This is associated with increased pelvic tilt, which leads to hamstring tightness or contractures. Therefore, a straight-leg raise test should routinely be performed.

• Patients may present with a stiff-legged, short-stride gait.

• As with suspicion of any deformity, a forward bending test should be performed to rule out a concurrent scoliosis, which is present in up to one-third of patients with SK.

• With forward bending, the SK patient will display a sharp (often 90 degrees) hump, as opposed to the rounded back seen in postural kyphosis.

• Flexibility testing and a complete neurologic exam should be performed.

– Neuroimaging

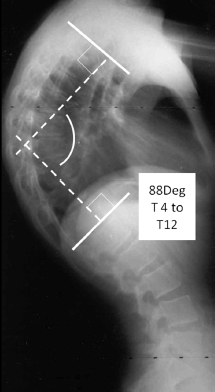

• Standing full-length PA and lateral views should be obtained. Diagnosis is made based on the lateral radiograph (Fig. 22.3). Sorenson defined SK as a thoracic kyphosis greater than 45 degrees with anterior vertebral body wedging greater than 5 degrees at three or more consecutive levels. Normal thoracic kyphosis is between 20 and 40 degrees.

• Posturalkyphosiscorrectsonhyperextensionlateralradiographs.

• Although Schmorl nodes are common in SK, they are not pathognomonic.

• MRI should be obtained only if a patient presents with neurologic symptoms.

Fig. 22.3 A full-length standing lateral radiograph of a 17-year-old male with Scheuermann kyphosis. This figure demonstrates the technique for measuring the degree of thoracic kyphosis, which in this patient is 88 degrees.

– Treatment

• The severity of the deformity (greater or less than 50 degrees), the age of the patient, skeletal maturity, and associated symptoms should all be considered in contemplating treatment.

• Nonoperative treatment ranges from observation with serial radiographs to postural exercises to bracing.

• Bracing is usually utilized in skeletally immature patients with a kyphosis of 50 to 75 degrees with an apex between T6 and T9. Studies have shown that bracing can achieve a 50% reduction in the kyphosis when worn full-time (>22 hours a day) for 12 to 18 months, followed by part-time (>12 hours a day) use until skeletal maturity is reached.

• Operative treatment should be considered in patients with kyphosis greater than 70 degrees, adults with residual deformity and intractable pain, a patient with progressive neurologic deficit, and skeletally immature patients who are poor candidates for bracing.4

• A posterior-only approach is indicated in patients with a kyphosis greater than 70 degrees that is correctable to 50 degrees. This approach avoids a thoracotomy, is technically less demanding, and decreases surgical time. Drawbacks are possible hardware failure and loss of 5 degrees of correction in long-term follow up.

– Surgical pearls

• Rigid curves that are not correctable to 50 degrees or less on the hyperextension lateral radiograph may require an anterior release prior to posterior fusion. Often these procedures are staged and entail longer hospital stay, higher blood loss, and the morbidity of a thoracotomy. Anteriorly, the ALL and the discs are removed at multiple levels to increase flexibility.

Common Clinical Questions

1. When is a MRI warranted in the workup of a patient with idiopathic scoliosis?

2. When planning for surgery in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, what levels should be included in the fusion?

3. What are the main differences between postural kyphosis and Scheuermann kyphosis?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree