24 Do’s and Don’ts in Pituitary Surgery

Dharambir S. Sethi and Beng Ti Ang

Introduction

Introduction

Pituitary surgery has been traditionally performed by neurosurgeons using a sublabial, transseptal, transsphenoidal approach and the operating microscope.1 The microscope provides excellent magnification, binocular vision, and a good depth of field essential for tumor removal. Transsphenoidal surgery has proven to be a safe and effective first-line therapy for most patients with sellar and suprasellar lesions. It is considered the “gold standard” and is effectively used by many pituitary surgeons around the world. More recently, since the description of endonasal resection of pituitary adenomas in three patients by Jankowski (an otolaryngologist) et al,2 there has been a surge of interest in endonasal pituitary surgery. In the past decade, endonasal surgery for pituitary tumors has gained acceptance worldwide.3–6

Working as a combined rhinology-neurosurgery team, we performed our first endoscopic pituitary surgery in October 1994. This has been a longstanding partnership; close to 500 pituitary tumors have been operated upon using direct endonasal techniques.

Our initial approach was transseptal.7 Though the results were encouraging, the transseptal approach had its limitations. One of the main limitations was having to work through a narrow tunnel created by elevating bilateral mucoperichondrial flaps on the nasal septum. Whereas the visualization was not compromised, instrumentation was often difficult, particularly when the situation required two surgeons to be working together while removing the tumor.

To overcome these limitations, we modified our approach to a direct endonasal transsphenoidal approach, avoiding a septoplasty and its inherent complications. This approach enables two surgeons to work through a common transnasal corridor using both hands and at times having four instruments in the operative field.8,9

This chapter provides some useful clinical pearls and pointers for practitioners venturing into endonasal pituitary surgery.10–15

Working As a Multidisciplinary Team

Working As a Multidisciplinary Team

Since the introduction of endoscopic sinus surgery almost 25 years ago, otolaryngologists have become trained and experienced in endonasal sinus surgery and endonasal approaches to the sphenoid sinus. This accumulated experience of endoscopic-trained otolaryngologists may be utilized by neurosurgeons in providing endonasal access to the sphenoid sinus and the floor of the sella. The otolaryngologist’s main roles during surgery are to provide relatively bloodless and unimpeded access to the sphenoid sinus through a wide midline sphenoidotomy, and to assist the neurosurgeon in tumor removal.

Although it is possible for a single surgeon to perform this surgery, a team approach is preferred. Once the initial approach is complete, both the neurosurgeon and the otolaryngologist can work together for the remainder of the procedure. In some situations it is important for the two of them to work together, with the otolarynologist holding the endoscope and providing manual manipulation of the endoscope to optimize the visualization, particularly near the end of the procedure when the angled scopes are used and the field of view is constantly changing.

Indications for Surgery

Indications for Surgery

Endoscopic transnasal-transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary tumors is indicated in both endocrine active and nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas. Indications for surgery include all nonsecreting and most secreting pituitary tumors except for prolactinomas, which are usually well controlled by medical therapy with dopamine antagonist.16

Pre- and Perioperative Evaluation

Pre- and Perioperative Evaluation

All patients scheduled for pituitary surgery must undergo radiologic evaluation, endocrine assessment, and visual field tests pre- and postoperatively. A preoperative nasal endoscopic examination by the otolaryngologist should also be a part of the routine preoperative assessment. We have, in our institution, developed a “pituitary surgery pathway” for patients undergoing this operation. This is to ensure strict perioperative management compliance by all specialists.

Imaging Studies

Although both computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been used for imaging of the pituitary gland, MRI has become the preferred modality. MRI scanning of the pituitary region involving fine cuts and sagittal and coronal reconstruction is the gold standard imaging method for pituitary disease.17 Radiologic evaluation should also include CT scans of the nose, paranasal sinuses, and sella turcica. CT scans are useful in studying the bony anatomy; moreover, calcified lesions such as craniopharyngiomas may be more easily identified with CT. CT scans are also a useful alternative to the MRI in patients who are claustrophobic and unable to tolerate an MRI study. The extent of sphenoid pneumatization, sphenoid dominance, internal sinus septa, and their termination on the optic nerve or the internal carotid artery are important anatomical considerations in planning transsphenoidal approach.

Although a conventional MRI scan of the pituitary fossa provides information about the location, size, and boundaries of the lesion and its relationship to adjoining structures, the prediction of the consistency of macroadenomas is controversial.18–20 Prediction of the consistency of pituitary tumors on diffusion-weighted (DW) MRI has recently been reported.21

Visual Field Testing

Progressive deterioration of visual fields is often the principal neurologic criterion on which surgical management decisions are based. Humphrey and Goldmann visual field evaluations are useful even if there appears to be no contact between the optic pathway and the pituitary mass, because field defects may reflect previous impingement, potential vascular shunting, or displacement of the chiasm following decompression.

Endocrine Evaluation

The perioperative endocrine management of a patient undergoing pituitary surgery may vary depending on the size of the pituitary lesion, the type of the lesion, the surgical approach (transsphenoidal, craniotomy), and the preoperative endocrine function.

Otolaryngology Assessment

A preoperative nasal endoscopic examination to exclude any active rhinosinusitis is undertaken by the otolaryngologist. Preoperative nasal endoscopy also provides useful information about the nasal anatomy, such as turbinate hypertrophy, concha bullosa, or a gross septal deviation that may necessitate a septoplasty for access to the sphenoid sinus. Preoperative treatment of nasal and paranasal sinus infections until there is complete return to normal is essential. Perioperative prophylactic antibiotics are routinely used.

Having the Right Setup

Having the Right Setup

One of the most important prerequisites for endonasal pituitary surgery is having a good videocamera system, sinus surgery and neurosurgical instruments, a dedicated neuroanesthesiologist, and assisting nursing staff members who have been specially trained for this type of surgery. Intraoperative neuronavigation and intraoperative MRI (iMRI) are not an absolute necessity but are employed in various institutions as adjuncts to maximize resection and also in expanded endonasal approaches.

Operative Setup

Operative Setup

The Digital Endoscopic Video Camera System (Karl Storz Endoscopy, Flanders, NJ) is placed at the cephalic end of the table to enable both surgeons to view the surgery on the video monitor. The neuroanesthetist is at the caudal end of the table. The scrub nurse and the instrument trolley are at the left cephalic end. Imaging studies are displayed for intraoperative reference. The otolaryngologist stands on the right side of the operating table and the neurosurgeon on the left side.

The digital video camera is attached to the eyepiece of the telescope, and the entire procedure is monitored on a 19-inch thin-film transfer (TFT) flat-screen monitor. Video documentation of the surgical procedure is routinely done on a digital video recorder. A powered sinus dissection device is used for the sphenoidotomy. We use the microdebrider developed by Medtronic (Jacksonville, FL). A 4-mm bit with a serrated outer shaft is used for mucosal dissection.

Surgical Technique

Surgical Technique

Patient Positioning and Preparation

The nasal cavity is decongested by placing two neuropatties soaked in 4% cocaine, in each side approximately 20 minutes prior to induction. The patient is placed under general anesthesia and administered antibiotics, glucocorticoids, and antihistamines. We routinely use cephazolin (2 g, intravenous), dexamethasone (10 mg, intravenous), and diphenylhydramine (50 mg, intravenous). Oral endotracheal intubation is used and a pharyngeal pack is placed in the pharynx. A Foley urinary catheter is routinely inserted to monitor urinary output intraoperatively and postoperatively. The patient’s head is placed on a horseshoe pad slightly extended, and turned slightly to the right. The head is elevated by approximately 30 degrees above the heart to facilitate venous drainage. Antiseptic solution (such as Povidine) is applied to the nose and mouth, and the area draped with sterile towels and a Steri-Drape. The lower abdomen is prepared and draped to obtain adipose tissue if necessary.

Nasal Preparation

The neuropatties that had been placed in the nasal cavity earlier are removed and discarded. The nasal cavity is once again decongested with topical application of cocaine. Sterile neuropatties soaked in 4% cocaine are endoscopically placed in the sphenoethmoid recess bilaterally. Allowing approximately 10 minutes for decongestion, the neuropatties are removed and the sphenoethmoid recess is infiltrated bilaterally, with 1% lidocaine with 1:80,000 epinephrine. A 21- gauge spinal needle is used for infiltration of the anterior wall of the sphenoid, sphenopalatine foramen, and the posterior part of the nasal septum.

Nasal Endoscopy and Identification of Sphenoid Ostia

After the nose has been adequately decongested an endoscopic examination is performed using a 0- or 30-degree endoscope (Karl Storz Endoscopy). The sphenoid ostia are identified bilaterally. The ostium lies just above the sphenoethmoid recess, approximately 1.5 cm above the choana. The shape and size of the sphenoid ostia may vary, but its location is almost constant. In some circumstances, the ostium is covered by a supreme turbinate, which can be gently retracted laterally or resected if necessary. Rarely, in the situation where the sphenoid ostium cannot be identified, entry into the sphenoid sinus can be gained using a blunt instrument or suction tip to exert controlled pressure to the anterior wall at the point of least resistance.

Midline Sphenoidotomy

Surgery is started on the side on which the sphenoid ostium is better visualized. Most of the time, we start on the right side. The microdebrider (with a 4-mm bit with a serrated outer shaft) is used to debride the mucosa in the sphenoethmoid recess around the sphenoid ostium, taking care not to traumatize the mucosa on the superior turbinates. The serrated blade of the microdebrider is directed medially and the outer sheath laterally, protecting the mucosa of the superior turbinate. The sphenoid ostium is widened inferiorly and medially down to the floor of the sphenoid sinus. Care is taken to avoid the septal branch of the sphenopalatine artery by not going too inferolaterally. Brisk bleeding may result if the septal branch of the sphenopalatine artery is encountered. This may be controlled by cauterizing the vessel with bipolar diathermy. In the rare situation where bleeding cannot be controlled, it may be necessary to expose and ligate the sphenopalatine artery at the sphenopalatine foramen, which is located in the superior meatus just posterior to the middle turbinate. Most endoscopic sinus surgeons are familiar with the technique.

If the bone of the sphenoid rostrum is thick, a 2-mm up- or down-biting Kerrison’s rongeurs may be used to extend the sphenoidomy. Sometimes firm but controlled tapping of a hammer against the osteotome or a drill may be necessary to remove the sphenoid rostrum.

Mucosa is debrided from the posterior part of the vomer and the sphenoid rostrum. The sphenoidotomy is extended to the contralateral side by dislocating the attachment of the vomer from the sphenoid rostrum. The sphenoid ostium on the contralateral side is identified, and the sphenoidotomy extended as far as the contralateral superior turbinate by removing the sphenoid rostrum. The sphenoid rostrum is removed with a strong septal forceps. A wide sphenoidotomy that extends superiorly to the roof of the sphenoid, inferiorly to the floor of the sphenoid sinus, and laterally to the superior turbinate on either side is fashioned.

Removal of the Posterior Nasal Septum

About 1 cm of the posterior part of the vomer is removed with a reverse-cutting forceps to facilitate the introduction of instruments from both nostrils. This step permits a panoramic view of the sphenoid sinus and enables the two surgeons to use both hands to introduce up to four separate instruments, two through each nostril. The access to the sphenoid sinus is complete. For a very wide access, necessary in some patients with large tumors requiring an extended approach, the entire posterior bony nasal septum may be removed to facilitate instrumentation.

From this point onward, the neurosurgeon and the otolaryngologist work as a team. The otolaryngologist manually manipulates the endoscope and assists the neurosurgeon in removal of tumor.

Identifying the Sphenoid Sinus Landmarks

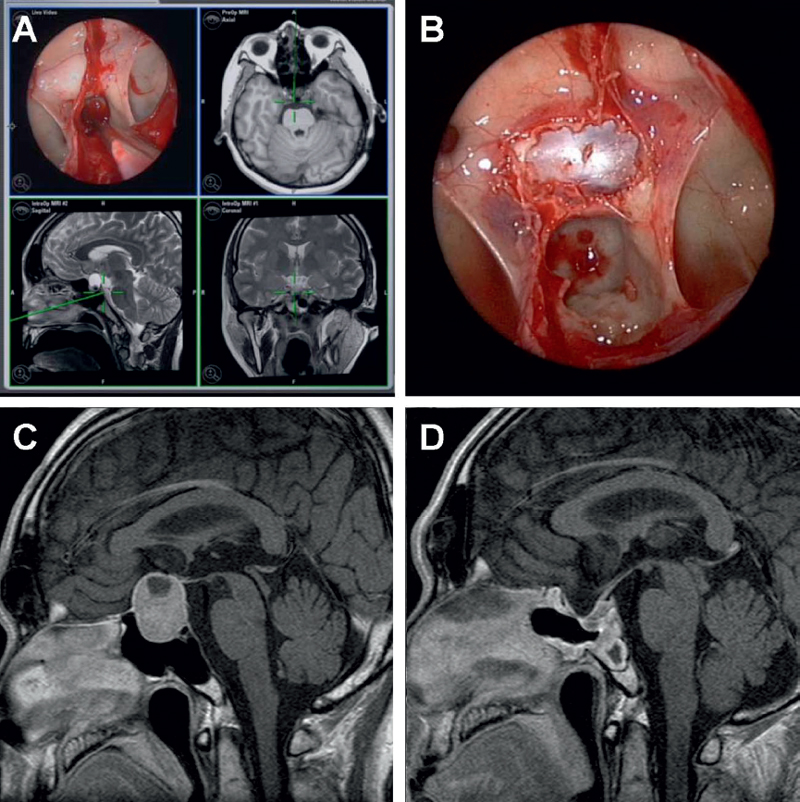

The sphenoid sinus is next examined with 0-, 30-, and 70- degree, 4-mm endoscopes, and important anatomical land-marks within noted (Fig. 24.1). Of particular importance are the structures on the lateral wall. The carotid prominence, optic prominence, and opticocarotid recess can be well identified when the sphenoid sinus is well pneumatized. On the lateral recess of a well-pneumatized sphenoid sinus, the second branch of the trigeminal nerve (V2) and the vidian canal may be identified superolaterally and inferomedially, respectively.

On the posterior wall, the tuberculum sella, the anterior wall of the sella, and the clivus are identified. The location of the intersinus septa, if any, is noted. If these septa have to be removed, extreme caution is exercised, as they often terminate on the carotid canal or the optic canal. It is safer to use Tru-Cut instruments to remove these septa. Injudicious avulsion of the septa with non–Tru-Cut instruments may cause fracture of the thin bone overlying the cavernous sinus or the optic nerve with resultant hematoma, intractable bleeding, or even blindness. Caution is also exercised in not stripping the sphenoid mucosa, as this may result in considerable bleeding.

Fig. 24.1 (A) Endoscopic image showing the interior of the sphenoid sinus with a perspective of the bony sellar floor bulging into the sphenoid sinus and the presence of intersinus septa. Adjunctive neuronavigation is also demonstrated where the position of the tip of the probe is displayed in sagittal, coronal, and axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance images. (B) The bony sellar floor has been resected, and the sellar dura is exposed. The planum sphenoidale and optic nerve prominences can be visualized superior to the sellar, and the intersinus septa can be seen inserting onto the carotid prominences on either side of the clival recess. (C,D) Pre- and postoperative T1-weighted magnetic resonance images, respectively, detailing the extent of resection.