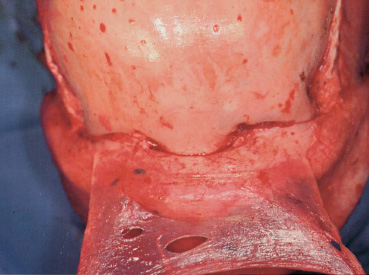

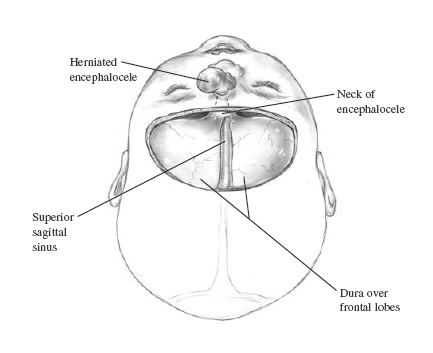

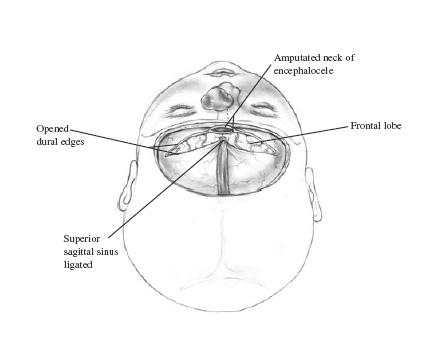

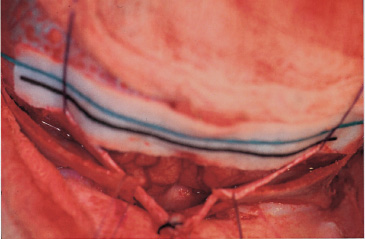

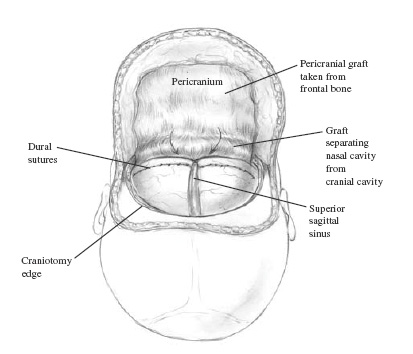

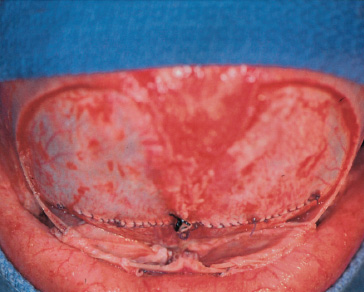

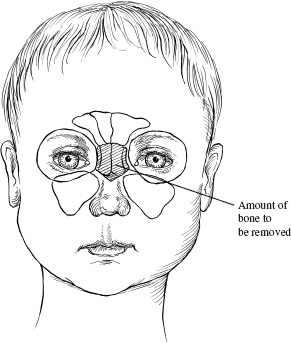

Although relatively uncommon in North America, the surgical correction of sincipital encephaloceles presents the neurosurgeon with a significant challenge. This chapter discusses surgical principles necessary to obtain an optimal surgical repair and results when managing these lesions. Additionally, the chapter introduces similar surgical principles necessary to successfully manage occipital encephaloceles and cranial dermal sinuses. Although sincipital encephaloceles are relatively uncommon in North America, they present the surgeon with a complex set of management issues. Ideally, these lesions should be treated by a craniofacial team with interest and experience in their management. The vast majority of patients present with normal intelligence and development, but because of the nature of the lesion, moderate to severe facial disfigurement is frequently seen and may be associated with psychosocial problems. The complexity of the surgical correction is dictated by the extent of associated craniofacial deformities. Besides resection of the encephalocele, other important issues that need to be addressed include correction of hypertelorism or telecanthus, vertical dystopia, and nasal deformities as well as management of nasolacrimal duct obstruction and epiphora. The input of a plastic craniofacial surgeon is essential for a successful outcome. Most of these lesions are evident at birth. Depending on the severity, they may present as a barely noticeable mass at or near the nasion or as a larger lesion with extension into the midface and orbits. Although the diagnosis is made clinically, at least a computed tomography (CT) scan should be obtained to delineate the bony involvement, the extent of the lesion, and the presence of associated neurologic anomalies. Hydrocephalus must be ruled out before any surgical correction is attempted. If available, a magnetic resonance (MR) scan also should be obtained to demarcate fully the extent of the encephalocele and to assist in preoperative planning. At least two large-bore peripheral intravenous lines are inserted, given the potential for significant blood loss. An arterial line is inserted to monitor blood pressure, blood gases, coagulation profile, hematocrit, and serum electrolytes. If the procedure is done in small children or infants, a warming blanket should be used to ensure proper temperature regulation and normothermia. A long anesthesia circuit should be used to allow the surgical team access to the patient’s head on all sides. A single dose of antibiotics (first-generation cephalosporin) should be given within 45 minutes prior to starting the procedure. If the operation lasts more than 6 hours, a second dose then is administered. Given the need for facial exposure and possible injury to the eyes, ocular shields should be inserted with ophthalmic lubricating ointment. These procedures are done with the patient under general anesthesia in a supine position, on the horseshoe with the head slightly extended to gain access to the entire anterior cranial fossa and face. The entire scalp and face should be prepared with povidone–iodine solution. The scalp is infiltrated with lidocaine 0.25% with epinephrine 1:400,000 for adequate hemostasis. The head need not be shaved except for a small area where the bicoronal incision is to be made. The hair is draped out of the working field with stapled towels posteriorly and 4 × 4 surgical sponges anteriorly. The shape of the incision is the surgeon’s choice, although many surgeons prefer a zigzag-type bicoronal incision because it provides better postoperative cosmetic results. The upper face is draped into the surgical field above the upper lips, placing povidone–iodine soaked cottonoids into both nostrils. A standard bicoronal scalp flap then is elevated using monopolar electrocautery (needle tip, low wattage) to create a bloodless subgaleal dissection plane. A separate pericranial flap is elevated from the most posterior aspect of the incision, extending laterally to the superior temporal lines and anteriorly to the supraorbital rims and nasofrontal suture (Fig. 4–1). Care should be taken to prevent injury to the supraorbital nerve and vessels. Described herein is the standard and currently accepted method for approaching sincipital encephaloceles. The procedure may be performed alone, followed later by the second stage of the procedure or as a combined single-stage approach. Most craniofacial centers currently perform a single-stage correction of these lesions. Following elevation of the bicoronal scalp and pericranial flaps, burr holes are strategically placed to elevate a bifrontal craniotomy. We have found it unnecessary to create multiple holes to raise the bone flap and only one or two located under the temporalis muscle below the superior temporal line (Fig. 4–2). The bone flap does not need to be large and should extend as close as possible to the supraorbital rims. In adolescents and adults, the frontal sinus should be preserved and not included with the craniotomy. FIGURE 4–1. Elevation of a separate pericranial flap is extremely important for proper closure. The distal end of the pericranial graft can be cut, and a free graft may be used to recreate dural closure and obliterate the bony defect. The remaining vascularized pericranial graft then is inserted under the dura and above the anterior cranial fossa. The dura is closed in a watertight fashion using a running interlocking braided nylon suture. Following elevation of the bone flap, the dura is exposed and in most patients with nasofrontal and nasoethmoidal encephaloceles, the neck of the lesion can be identified easily (Fig. 4–3). For basal encephaloceles, exposure of the neck requires posterior dissection over the cribriform plate or planum sphenoidale. The dura is opened over the frontal lobes, immediately above the supraorbital rims. The sagittal sinus is doubly ligated with 00 silk and cut between dura openings (Fig. 4–4). The dural incision then is taken posteriorly to include the falx cerebri. Elevation of the frontal lobes should expose the neck of the encephalocele. Bipolar electrocautery is used to cauterize the cortical surface of the neck, and suction can be used to amputate the lesion flush with the cranial base (Fig. 4–5). As much of the gliotic, herniating mass as posible should be resected from the bony canal. A free pericranial graft then is used to close the dural defect in a watertight fashion with 0000 braided nylon (Fig. 4–6). A vascularized pericranial graft then is laid over the dura and the cranial fossa floor. Often, following resection of nasofrontal encephaloceles, large areas of dead space are created at the resection site. We prefer to use vascularized pericranial grafts to manage these spaces. As previously described, a large pericranial flap is elevated, the blood supply of which is based on the supraorbital vessels. The lateral edges extend along the superior temporal lines, and the posterior edge extends several centimeters behind the coronal suture. The grafts can be divided longitudinally into thirds. The medial third is used for reinforcement of the dural patch graft and coverage of the nasal bone grafts. The lateral thirds are brought down into the resection site through small osteotomies located in the superior medial orbital walls (Fig. 4–7). The grafts are used to line the walls and fill the cavities. This maneuver is particularly important if entrance into the nasal cavity occurs during the resection of the encephalocele. If there is a large bony defect, an autologous split-thickness calvarium can be harvested to reconstruct the bony defect. Proper dural closure is followed by replacement of the bone flap, which is rigidly fixated with microplates. FIGURE 4–3. The classic approach to sincipital encephaloceles requires a bifrontal, intradural exposure to the neck of the encephalocele. A bifrontal craniotomy is created, thereby allowing exposure of the floor of the anterior cranial fossa and the area of the foramen cecum. FIGURE 4–4. Following bifrontal exposure, the dura on either side of the sagittal sinus is opened. The sinus is doubly ligated with 2.0 silk sutures. After transection of the sinus, the frontal lobes and the encephalocele are exposed. The neck of the lesion is transected flush with the floor of the anterior cranial fossae using bipolar electrocautery or ultrasonic aspiration. FIGURE 4–5. The area of the glabella also may be resected to improve visualization of the encephalocele. Intraoperative photograph shows removed glabella, ligated sagittal sinus inferiorly, and neck of the encephalocele. A cottonoid has been placed over the frontal lobes. Although previously unreported, in our series, we have found a high incidence of nasolacrimal apparatus blockage in patients with frontal encephaloceles. Early surgical experience resulted in several nasolacrimal duct infections following resection of the encephalocele without treatment of the blockage. Currently, we proceed with nasolacrimal duct cannulation prior to resection. A punctal dilator is used to probe and dilate the superior and inferior puncta, followed by insertion of the Crawford guidewires. These guidewires are attached to a long Silastic tube. The guidewires are guided medially and then inferiorly to exit in the nasal cavity under the inferior turbinate. The ends of the Silastic tube then are ligated, cut, and left in place for 6 months. Once removed, a patent nasolacrimal system should be present, thereby relieving the symptoms associated with obstruction. We have found this management protocol to be extremely helpful in the care of these patients. FIGURE 4–7. Dural closure in a 3-month-old infant following resection of nasoethmoidal encephalocele. Braided nylon is used to close the dural opening. Note the placement of the lateral pericranial grafts under the orbital surface of the frontal lobes. A subgaleal drain is left in place for 24 to 36 hours postoperatively. If the patient is hyperteloric, hypertelorism correction can be carried out prior to closure of the bicoronal incision. Preferably, radial osteotomies are carried along the superior, medial, inferior, and lateral anterior orbital margins. Following resection of the widened nasal bone, medial orbital transposition osteotomized orbits is done along with medial canthopexy. In the past, strictly extracranial approaches to sincipital encephaloceles have proven to be unsatisfactory for treatment of these lesions. Although the extracranial part may be resected easily proper dural closure is sometimes difficult to obtain, leading to a higher incidence of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks and infection. Currently, there is consensus among craniofacial and neurologic surgeons that, given current available techniques, endoscopic approaches to repair encephaloceles are not warranted and are associated with greater risk of infection, meningitis, inadequate resection, and CSF leaks. Our method of choice for treating nasofrontal, na-soethmoidal, and nasomaxillary encephaloceles involves modification of the aforementioned methods. We have found it unnecessary to perform a bifrontal craniotomy to do an adequate repair (Fig. 4–8). A standard bicoronal flap is elevated as described. Using a high-speed drill (Midas Rex, Ft. Worth, Texas) a straight bit (C1) is used to create a small nasofrontal craniotomy. The osteotomies are made along the lateral edges of the nasal bone, medial to the orbits, and superiorly across the root of the glabella. This section of the nasal bone is carried out distally to the end of the nasal dorsum. The unit is elevated with a small elevator, and the entire unit is removed, thereby exposing the neck of the encephalocele and unroofing its bony canal (Fig. 4–9). The dura is incised at the level of the nasofrontal suture, and the neck of the encephalocele is resected. Resection is carried out directly posteriorly reaching the anterior margin of the cribriform plate (Fig. 4–10). Elevation of the dura from the anterior fossa is carried out circumferentially around the bony defect. A free pericranial graft is sutured to the surrounding dura. Fibrin glue may be used to seal the defect further. If fibrin glue is not available or if one chooses not to use it, a spinal drain may be inserted pre-operatively and left in place for several days during the postoperative period. A vascularized pericranial graft then can be used to compartmentalize the cranial and nasal cavities (Fig. 4–11). The herniating mass then can be resected and delivered through the nasal opening, even if it extends into the orbit or maxillary sinus. If the skin overlying the herniating mass is of normal texture, it is left alone and dermapexy sutures are placed for proper contouring. If the skin is grossly abnormal, it is resected and properly closed. Hypertelorism may be corrected using this approach without the need for bifrontal craniotomy. The small bone graft is rigidly fixated in situ to obtain proper frontonasal contour (Fig. 4–12).

ANTERIOR CRANIAL FOSSA ENCEPHALOCELES

Surgical Indications

Operative Planning

Intraoperative Techniques

Intracranial Approach

Extracranial Approaches

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree