17 Endoscopic Endonasal Approach for Anterior Skull Base Meningiomas

Amin B. Kassam, Daniel M. Prevedello, Paul A. Gardner, Juan C. Fernandez-Miranda, Ricardo L. Carrau, and Carl H. Snyderman

Introduction

Introduction

Treatment for skull base tumors has significantly evolved1–4 since Dandy5 first described the removal of a cranial base/orbital tumor via a craniotomy in 1941. This early effort was followed by Smith et al’s6 description of a combined transfacial-transcranial approach for the removal of a skull base tumor originating in the frontal sinus. However, it was not until the 1960s that Ketcham et al7,8 described the first craniofacial resection using a coronal incision and craniotomy combined with facial incisions for removal of sinonasal tumors. Over the subsequent decades, surgical techniques were refined, but the field of skull base surgery changed slowly. In 1997, Yuen et al9 described an endoscopic-assisted craniofacial resection applying the principles and instruments developed for inflammatory endoscopic sinus surgery to surgically address a malignant neoplasm. In 1999, Stammberger et al10 described the endoscopic resection of an esthesioneuroblastoma. Since then, multiple case series have reported good results following endoscopic resection of esthesioneuroblastomas and other neoplasms of the skull base.11–15

Transsphenoidal approaches followed a similar evolution. Guiot et al16 in 1963 proposed using the endoscope for transsphenoidal procedures, and Apuzzo et al17 revisited this concept in 1977. In 1984, Griffith and Veerapen18 utilized the pure endonasal technique to approach the sella for excision of a pituitary adenoma. Jho and Carrau19 decisively established this as a purely endoscopic technique in 1997, and, subsequently, De Divitiis and Cappabianca’s group20,21 expounded on the advantages the nuances of such an approach. In 2001, Jho22 reported the first patient to undergo an endoscopic, endonasal resection of an intracranial meningioma compressing the optic nerve. Kelly’s group,23 in 2004, reported on three patients in whom the endonasal route with endoscopic support was used to resect suprasellar meningiomas, achieving good short-term results.

The goals of a skull base resection, endoscopic or open, remain the same: complete tumor extirpation with negative margins for oncologic cases, and separation of the cranial cavity and sinonasal tract.24 Regardless of the approach, when dealing with benign disease, such as meningiomas, the surgeon must minimize surgical morbidities such as neurologic sequelae, visual dysfunction, or cognitive impairment. Cosmesis, although not the primary goal, is an important concern, especially when undergoing extensive open procedures. Advanced endoscopic techniques facilitate extensive resections without the need for external incisions.25–27

Currently, the literature lacks a systematic review comparing open techniques to endoscopic techniques for meningiomas. A recent systematic review compared endoscopic and open techniques for treatment of sinonasal inverting papillomas.28 In patients treated endoscopically, the recurrence rate was significantly lower than for those treated nonendoscopically (12% versus 20%). Casler et al29 compared endoscopic and open techniques for pituitary surgery in a cohort study, and noted that patients undergoing transsphenoidal endoscopic resection of adenomas experienced less pain, less blood loss, fewer complications, and shorter length of stay in the intensive care unit and hospital. Additional benefits include superior visualization, lack of incisions, a reduction in swelling, and decreased pain and bleeding.30,31 However, the surgical indications for endoscopic and open approaches are not necessarily the same, and comparing these heterogeneous groups of patients may yield misleading conclusions. Nonetheless, we believe that there is a critical advantage for endonasal resection of tumors such as meningiomas that originate in the median skull base and do not extend laterally to involve critical neurovascular structures.

Indications and Advantages

Indications and Advantages

Anterior skull base meningiomas, including those originating at the olfactory groove, planum sphenoidale, and tuberculum sellae, are challenging tumors despite well-described transcranial approaches. These tumors are often associated with significant cerebral edema and distortion of the optic apparatus, thereby requiring some degree of frontal lobe retraction and manipulation of the optic apparatus for their access and resection. Furthermore, these tumors originate at the base of the skull base, and as such they are always in direct contact with the roof of the sinuses. The endoscopic endonasal approach (EEA) takes advantage of this anatomic relationship to enable resection of the meningioma without brain retraction.32

Once the approach is performed, these skull base tumors are managed in a manner similar to that used for convexity meningiomas. The tumor’s main blood supply is coagulated before the dissection. For olfactory groove meningiomas, the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries are coagulated or ligated early during exposure, and the dura mater is broadly coagulated before the dural opening. McConnell’s arteries are coagulated before accessing tuberculum sellae meningiomas. In summary, there is decreased neurologic tissue manipulation, and the tumors are devascularized early during the endonasal approach (Figs. 17.1, 17.2, and 17.3).25

Contraindications

Contraindications

The endoscopic endonasal route approaches the anterior skull base pathology from a medial, anterior, and inferior trajectory; therefore, there are potential surgical limits laterally, posteriorly, and superiorly. In reality, these limitations can be minimized as long as safety and vascular control are maintained.

The lateral limit of resection for olfactory groove meningiomas is the midorbital plane (Figs. 17.1A,B and 17.2A). Removal of the lamina papyracea enables the displacement of the orbital soft tissues to provide access to the orbital roof laterally. Lesions that present a lateral extension beyond the midorbit meridian should not be accessed with a pure endonasal approach.

The posterior limit for an EEA is essentially the same as for any anterior skull base approach—the optic chiasm and anterior cerebral circulation. Meningiomas tend to displace the optic nerves laterally, the chiasm posteriorly, and, in most of the cases, the anterior cerebral and communicating arteries are displaced superiorly and posteriorly (Fig. 17.2B). Tumors lateral to the optic nerves should not be resected from a midline endonasal approach.

Very tall tumors can be difficult to access and care must be taken not to remove too much of the inferior and anterior capsule before the apex of the tumor has been debulked. The frontal lobes can descend into the field, obscuring the view. Sometimes these tumors need to be resected in stages, after a significant initial debulking allows descent of the tumor. The surgical team needs to be comfortable with the use of angle endoscopes. Commonly, most of the delicate dissection of an anterior fossa meningioma is performed with a 45-degree endoscope.

Diagnostic Workup

Diagnostic Workup

The physical examination should include a neurologic assessment with special focus on cranial nerve function. Olfaction is compromised by most olfactory groove meningiomas, but its function must be documented preoperatively. Endoscopic assessment of the nasal cavity is recommended to visualize any nasal lesions and document septal integrity, septal deviations, and any other anatomical findings. A complete ophthalmologic examination is mandatory for anterior fossa meningiomas and must include visual fields examination. Signs of intracranial hypertension detected by papilledema should be addressed preoperatively. These cases frequently require preoperative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) diversion with external ventricular drainage (EVD) or ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt to control the pressure and for vision protection.

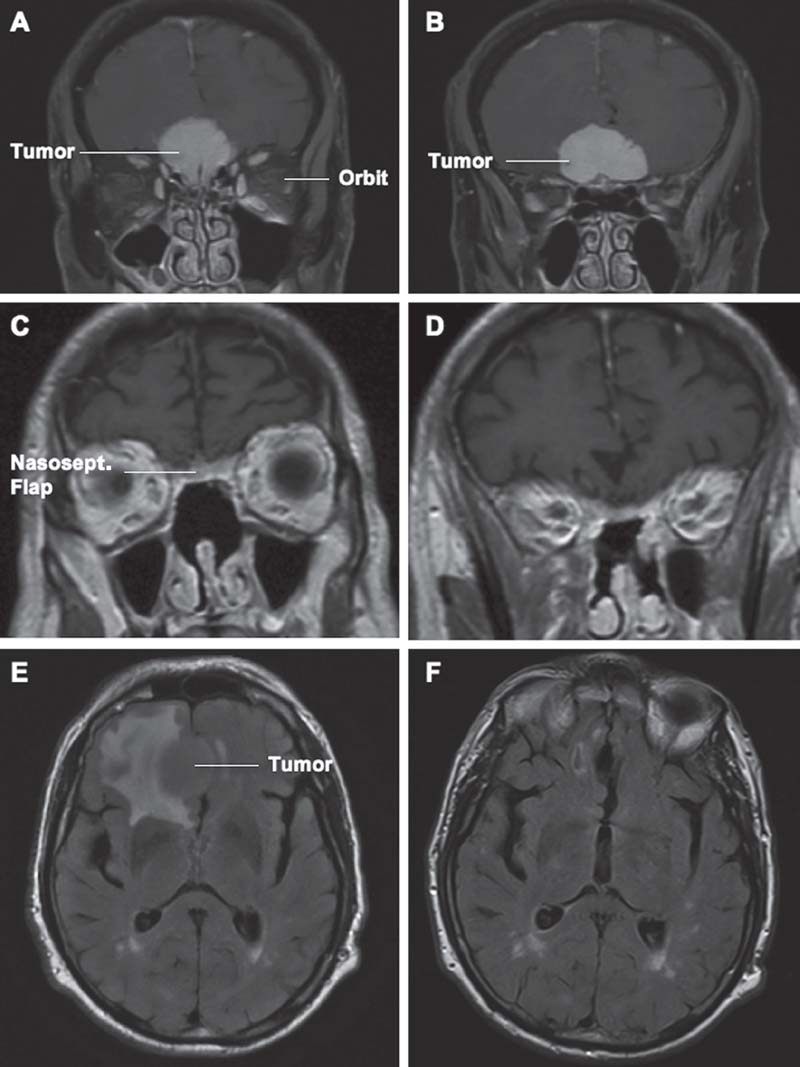

Fig. 17.1 Moderate-size olfactory groove meningioma. (A) Preoperative T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) coronal section at the level of the cribriform plate. (B) Preoperative T1-weighted coronal section at the anterior level of the planum sphenoidale. (C) Sixmonths postoperative T1-weighted coronal section showing complete resection of the tumor and removal of the cribriform plate and crista galli. Note the natural enhancement of the nasoseptal flap used for reconstruction of the anterior skull base defect. (D) Postoperative T1-weighted coronal section showing complete resection of the tumor and minimal encephalomalacia. The tumor has been removed without any need for brain retraction or manipulation. (E) Preoperative fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequence axial section showing significant signal change at the right frontal lobe. (F) Postoperative FLAIR sequence axial section showing nearly complete resolution of the signal changes. Nasosept.: nasoseptal.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree