19 Endoscopic Transnasal Craniectomy and the Resection of Extensive Craniopharyngiomas

Richard J. Harvey, Aldo Cassol Stamm, Daniel Timperley, and Eduardo Vellutini

Introduction

Introduction

Craniopharyngioma is an uncommon benign tumor, accounting for 2 to 5% of all intracranial neoplasms.1 Distribution by age is bimodal, with the peak incidence in children at 5 to 14 years of age and in adults at 65 to 74 years of age, with an incidence of 0.14 to 2 per 100,000.2,3 Although total surgical removal is the aim of the treatment, craniopharyngioma is a difficult tumor to excise completely. Morbidity from an intrapial tumor adherent to the pituitary stalk, hypothalamus, and anterior cerebral vessels has always dictated the completeness of resection. Tumor involvement of these structures combined with poor surgical access, limited instrumentation for sharp dissection, and limited visualization of the anatomical relationships has often hindered dissection regardless of the approach. The use of endoscopes in surgery for these lesions has been particularly successful, allowing minimal operative morbidity, direct access to pathology, and detailed visual assessment of anatomy and resection limits (Harvey laryngoscope). For craniopharyngioma, effective and safe treatment of lesions involving the skull base is still a challenging problem.

Debate exists regarding the histologic description of craniopharyngiomas. Currently, three theories are widely accepted, and from these, the adamantinomatous, squamous papillary, and mixed variants have been derived. They are as follows:

• Embryogenetic theory: the adamantinomatous type (“adamantinoma”) arises from epithelial remnants of the Rathke pouch or the precursors to the adenohypophysis and infundibulum migrate. Rests can occur from the pharynx to the sella turcica and third ventricle.

• Metaplastic theory: the squamous papillary type results secondary to metaplasia of squamous epithelial cell rests that arise from squamous cell nests of the pituitary stalk and pars distalis junction.

• Variant of midline congenital cyst: the variant is a midline congenital tumor not fundamentally different from an epidermoid cyst.

Craniopharyngiomas are usually composed of both solid and cystic components. Cyst walls are lined with stratified squamous epithelium with pearly keratin formations. An outer layer is columnar epithelium. Calcifications occur 90% of children and 40% in adults. A “motor oil” description is often given to the cystic fluid.

Subfrontal and pterional craniotomies have been the traditional approaches to extensive craniopharyngioma with suprasellar extension.4 The transsphenoidal route had been previously reserved for purely intrasellar tumors. The extended transsphenoidal transplanum endoscopic5 approach may benefit patients with extensive craniopharyngioma (Fig. 19.1), facilitating direct access to pathology, minimizing brain retraction, and reducing manipulation of the optic chiasm, the hospital stay,6 and morbidity.7

Morbidity from the open approaches may be significant, especially when surgical resection is subtotal. The balance of surgical morbidity and long-term control is a decision for the patient and the operative team. Karavitaki et al8 recently reviewed the literature on the long-term outcomes in craniopharyngioma. Accepted 10-year recurrence-free survival rates were 74 to 81% after gross total resection, 41 to 42% after partial removal, and 83 to 90% after surgery (defined as partial or minimal resection) and radiotherapy. The aggressiveness of craniopharyngioma in adults compared with children has been debated. There appears to be little evidence supporting a substantial difference in behavior from larger cohorts.8–10

Fig. 19.1 Extensive suprasellar craniopharyngioma on computer tomography (CT). Sagittal view. Note calcification, which is common within large tumors.

Fig. 19.2 Visualization via the endoscopic transnasal craniectomy. Two-surgeon dissection is performed. Note optic chiasma and residual tumor being removed.

The extended transsphenoidal approach has been described with microsurgical dissection,11–17 and extensive nonadenomatous tumors have been managed with these techniques.13 The use of an extended sellar opening by removing the sphenoid planum and tuberculum sellae is described in these series.13 This route is often the first option even for suprasellar lesions.17 Transsphenoidal approaches have gained wide acceptance because they offer direct access to the tumor site and avoid the morbidity of transcraniectomy surgery.17 Subsequently, the transsphenoidal approach has evolved to a totally endoscopic transnasal surgery.18 A large transnasal craniectomy is not hampered by a long narrow surgical corridor, which previously combined both vision and surgical instruments (Fig. 19.2). Visualization can be superior with an endoscopic approach compared with the microsurgical access.19

Indications and Advantages

Indications and Advantages

Broadly, the goals of transnasal craniectomy for craniopharyngioma should include the following:

• Removal of disease and prevention of regrowth

• Relief of hydrocephalus

• Decompression of the optic nerve and chiasm

• Minimal functional loss

o Vision

o Other cranial nerve integrity

o Pituitary/hypothalamic function

o Orbital function

An understanding of the significant complications associated with surgery, whether neurologic, orbital, endocrine, or infectious, is paramount for an informed discussion with a patient considering craniopharyngioma resection.

Contraindications

Contraindications

Contraindications include the following:

• Acute/subacute sinusitis

• No multidisciplinary team available

• Lack of specialized equipment

Relative situations that may lead to poor outcomes include tumor size >4 cm, patient age <5 years, severe hypothalamic dysfunction preoperatively, and a surgical approach that is overly focused on total resection without balancing the impact of morbidity.

Diagnostic Workup

Diagnostic Workup

Radiologic Assessment

Tumor classification is based on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), and intraoperative findings. The size, position relative to the optic chiasm (pre- or postchiasmatic), and the vertical extension is recorded. The extension vertically is defined as a combination of sellar, suprasellar, or ventricular. The suprasellar or intracranial extension can be categorized as C, D, E, or F by the Yasargil20 classification.

Endocrinologic Assessment

All patients should undergo assessment by an endocrinologist, which should include the following:

• Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH or corticotropin)

• Growth hormone (GH) and insulin growth factor (IGF-1)

• Cortisol

• Prolactin

• Thyrotropin (thyroid-stimulating hormone [TSH])

• Triiodothyronine (T3)

• Thyroxine (T4)

• Luteinizing hormone (LH)

• Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)

The diagnosis of preoperative diabetes insipidus should be made with serum sodium levels and osmolarity, together with urine specific gravity and osmolarity. Hypothalamic injury, including appetite dysfunction and violent behavior, should be assessed. Any abnormalities should be corrected preoperatively, but, at the very least, low cortisol levels and diabetes insipidus should be treated prior to any surgical procedure.

Ophthalmology Assessment

Visual acuity and visual field assessment are required to delineate any deficit, including papilledema. Formal visual assessment is performed by an ophthalmologist. Other cranial neuropathies need to be documented.

Surgery

Surgery

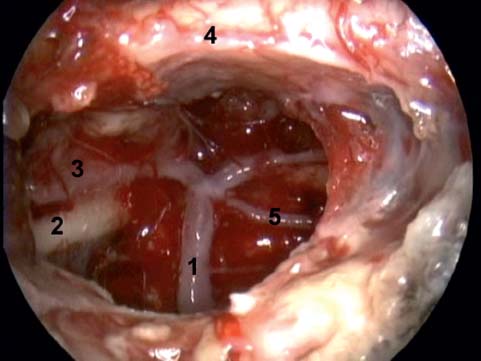

A large transnasal craniectomy forms the basis of our intradural endoscopic procedure. It provides optimal visualization of pathology (Fig. 19.3) and critical anatomy, and entails less manipulation of brain tissue and easy access for several instruments. This is fundamentally different from the small sellar floor openings that are described in most adenomatous pituitary surgery.21 The wider approach also enables two surgeons to work concomitantly binasally without constant criss-crossing of instruments. The endoscopic route may also provide unoperated surgical planes when multiple previous open approaches have been performed.

Instruments

Endoscopic craniopharyngioma is highly dependent on specialized instrumentation, and its absence is an absolute contraindication to surgery. Dissection instruments and drills that are appropriately long enough to perform dissection beyond the sphenoid are essential. Similarly, high-quality endoscopes and video equipment is required. It is not appropriate to perform endoscopic skull base surgery (SBS) without camera equipment. The operative team needs to be visually informed of the state of surgery. A second surgeon, for bimanual dissection, and the operating room staff should be actively involved. The ability to maintain hemostasis and a workable operative field during prolonged surgery is a demanding aspect of extended endoscopic surgery. Long endoscopic bipolar forceps and hemostatic materials such as Surgicel or Avitene are essential to this process.22

Fig. 19.3 Large transnasal craniectomy. 1, basilar artery; 2, third cranial nerve; 3, posterior cerebral artery; 4, optic chiasm; 5, superior cerebellar artery.