Endovascular Anesthesia and Medications

As neuroendovascular surgery becomes more sophisticated with regard to procedural and medication variety, careful preprocedural patient risk stratification is essential for determining potentially dangerous side effects and/or interactions secondary to medication administration. This chapter discusses the core preprocedural and periprocedural care, medications, and endovascular agents associated with neuroendovascular procedures.

Sedation

As angiography suites have advanced in terms of equipment used, such as flat-panel displays, so have the staff involved in the care of the patients: for example, angiography/neurospecific nursing, using patient monitoring capabilities, neuroanesthesia, etc. As a result, an increasing number of neuroendovascular procedures are being performed with sedation as opposed to general anesthesia. Consequently, in 2002 the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) redefined sedation levels (Table 4.1).1

Table 4.1 ASA Definition of Sedation

Type of anesthesia | Definition |

Minimal sedation | Patient has normal response to verbal stimulation, the airway is not compromised, and the ventilatory and cardiovascular functions remain unaffected. |

Moderate sedation/analgesia (conscious sedation) | Patients have purposeful response to verbal or tactile stimulation, no airway intervention is required, there is adequate spontaneous ventilation, and usually cardiovascular function is unaffected. |

Deep sedation/analgesia | Patient has purposeful response after repeated or painful stimulation. There may be a need for airway intervention, with a possibility of inadequate spontaneous ventilation and with usually intact cardiovascular function. |

General anesthesia | Patients are not arousable, even with painful stimulation. Airway intervention is required, spontaneous ventilation is frequently inadequate, and cardiovascular function may be impaired. |

Risk Stratification

The ASA Physical Status Classification2 addresses risks associated with the performance of surgical procedures based on the patient’s presurgical morbid state (Table 4.2).

The Mallampati Score3

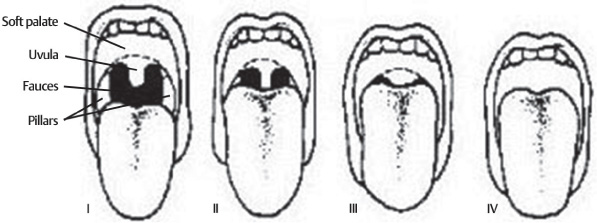

The Mallampati score (Table 4.3), utilized to determine the ease of intubation, is based on oropharygeal anatomy (Fig. 4.1) and vocal cord visualization. The thyromental distance assesses ease of intubation. If the distance is less than 6 cm, intubation is likely to be difficult. When combined with neck flexibility, this score provides the practitioner a good idea of the potential risks of endotracheal intubation if deeper sedation becomes necessary.

Before determining the type of sedation, the interventionist must investigate preprocedural morbidities to avoid inadvertent complications amenable to prevention. It is important to determine such conditions as a history of arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or renal insufficiency; allergies to shellfish, contrast agents, sulfa drugs, or anesthetic agents; familial hyperthermia secondary to anesthesia (malignant hyperthermia); intolerance to local anesthetics; intolerance or resistance to anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents; and hypersensitivity to heparin, protamine, aspirin, clopidrogel, and diverse antibiotics.

Score | Description |

1 | Normal, healthy patient |

2 | Mild systemic disease |

3 | Severe systemic disease |

4 | Severe systemic disease, at constant risk of death |

5 | Moribund patient, not expected to survive the operation |

6 | Brain-dead patient |

Table 4.3 Mallampati Preintubation Scoring System

Score | Description |

Class I | Soft palate, fauces, uvula, and pillars well visible |

Class II | Soft palate, fauces, portions of uvula |

Class III | Soft palate, bases of uvula |

Class IV | Hard palate only |

Fig. 4.1 Mallampati anatomical landmarks.

Sedation-Agitation Scores

Sedation-agitation scores were developed to help assess the depth of sedation in patients during procedures or in those unable to cooperate with the neurological examination. Progression from one level of sedation to another helps in determining preventive or reversal measures.3 Evaluation of sedation and pain in children may be challenging but is rather important, in particular with the increasing number of neuroendovascular procedures performed on the pediatric population. The following are the most commonly used scales:

1. Ramsay Sedation Scale: Developed to assess the level of consciousness during titration of sedative medications. Easy to use and reproduce (Table 4.4).

2. Sedation Agitation Score: Developed to determine the depth of sedation in the general ICU. Easy to use, although not appropriate for non-English-speaking, hearing-impaired, or neurologically compromised patients4 (Table 4.5).

3. Richmond Sedation Scale: Developed to assess the daily level of sedation in the general intensive care unit. Easy to administer, it values eye contact between patient and examiner as a key point on sedation assessment. Reliable and reproducible5 (Table 4.6).

4. Critical Care Pain Observational Tool (CCPOT): Integrates different pain assessment tools into one useful scale for pain assessment in adults who are awake or intubated3 (Table 4.7).

5. University of Michigan Sedation Scale (UMSS): Developed for rapid, reproducible, and reliable evaluation of sedation in children6 (Table 4.8).

6. The Bi-Spectral Index: An EEG modality for interpreting cortical activity. Scores vary from 0 (no cortical activity) to 100 (fully awake). It may interfere with electromyography if patients are not adequately sedated. However, it has shown excellent correlation with other available sedation scales.7–9

Table 4.4 Ramsay Sedation Scale

Score | Definition |

1 | Anxious, agitated, restless, or all of them |

2 | Cooperative, oriented, and tranquil |

3 | Responds to simple commands only |

4 | Brisk response to light glabelar tap or loud auditory stimulation |

5 | Sluggish response to light glabelar tap or loud auditory stimulation |

6 | No response to light glabelar tap or loud auditory stimulus |

Table 4.5 Sedation Agitation Score

Score | Definition | Description |

7 | Dangerous agitation | Pulling catheters, climbing over bedrail, combative |

6 | Very agitated | Requires restraints, does not calm down despite frequent verbal enforcement |

5 | Agitated | Agitated but calms down to verbal commands |

4 | Calm and cooperative | Calms, awakens easily, follows commands |

3 | Sedated | Awakens to verbal and tactile stimuli but drifts down shortly afterwards |

2 | Very sedated | Arouses to physical stimulation, does not communicate or follow commands. May move spontaneously. |

1 | Unarousable | Minimal or no response to noxious stimuli. No commands or communication. |

Table 4.6 Richmond Sedation Scale

Term | Description | Score |

Combative | Immediate danger to staff | 4 |

Very agitated | Pulls or removes tubes, catheters, or is aggressive to staff | 3 |

Agitated | Frequent non-purposeful movements or patientventilator dyssynchrony | 2 |

Restless | Anxious or apprehensive but movements not aggressive or vigorous | 1 |

Alert and calm |

| 0 |

Drowsy | Sustained, greater than 10 seconds awakening, with eye contact, no voice | −1 |

Light sedation | Briefly (<10 seconds) awakens with eye contact to voice | −2 |

Moderate sedation | Any movement to voice, without eye contact | −3 |

Deep sedation |