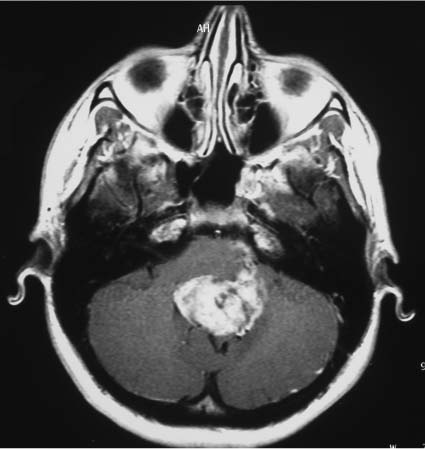

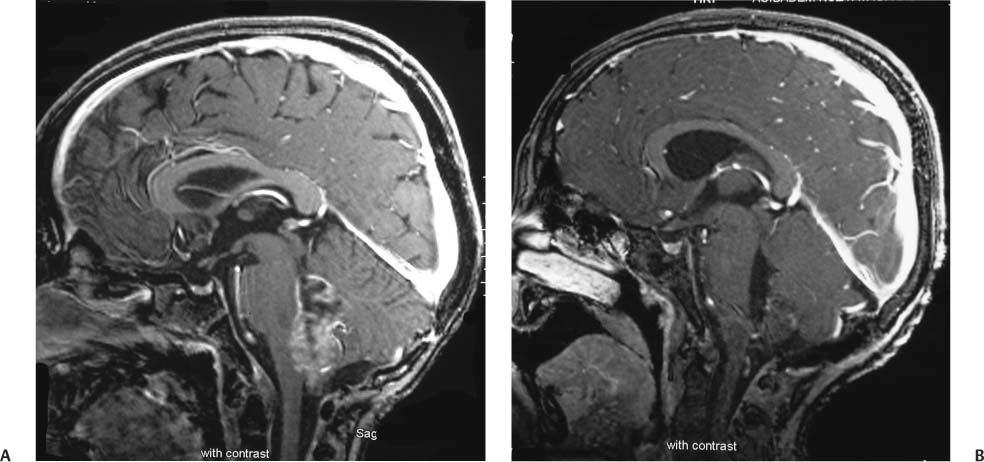

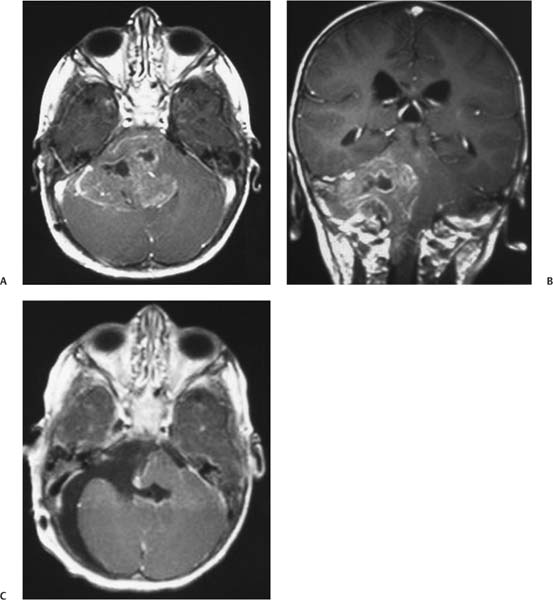

8 Ependymomas Ependymoma arises from the ependymal cells that line the cerebral ventricles and central canal of the spinal cord. It is the third most common brain tumor in children,1 with ~70 to 80% of the cases presenting in children younger than 8 years of age.2–4 Two thirds of patients with intracranial ependymomas present with posterior fossa tumors, and 7 to 15% present with disseminated disease at diagnosis5,6 (Fig. 8.1). The optimal treatment of these tumors is surgical resection.6–11 The most significant prognostic factor predicting survival in children with ependymomas is the extent of surgical resection.7,8,11–18 Location, histology, and other prognostic variables appear to have a minor impact on long-term survival rates in comparison to the extent of surgical resection.6,9,18–20 The 5-year survival rate for ependymomas has been found to be between 60 and 89% after gross total resection (GTR), but this decreases to 21 to 46% in incompletely resected tumors.2,7,15,21–24 The frequency of complete resections ranges from 25 to 93% for supratentorial ependymomas and from 5 to 72% for infratentorial ependymomas despite the presence of novel surgical techniques.6,18,25–29 However, in some instances, a preoperative plan for a subtotal resection in ependymoma is the rule: on imaging studies, the presence of a lesion that involves the pontocerebellar angle refers to infiltration of most cranial nerves and diffuse infiltration of the floor of the fourth ventricle, indicating a preoperative subtotal removal plan for the neurosurgeon (Figs. 8.2 and 8.3). Similarly, GTR of a tumor infiltrating the pons usually would be extremely difficult and morbid for the patient, if not impossible and lethal. The presence of a distant metastasis on full neuraxis imaging should also have a major impact on the goals of surgery, such as planning subtotal removal rather than GTR preoperatively. It has been established that the rate of GTR is dependent on location, being up to 100% in the roof of the fourth ventricle, 86% in midfloor tumors, and 54% in the lateral recesses.18 It is well known that the extent of resection is the strongest prognostic factor for survival rates. Subtotal resection is sometimes preoperatively planned by the neuro-surgeon; sometimes the presence of a subtotal resection is reported postoperatively either by the neurosurgeon or by the imaging studies performed in the early postoperative days. Even in patients for whom complete resection cannot be obtained, the Children’s Cancer Group (CCG) 921 trial suggests that a residual tumor measuring 1.5 cm2 predicts improved survival.6 Reoperation with attempted complete resection, when safe and feasible after initial resection, allows proven survival benefits in children with ependymoma and residual bulky disease.12,30–32 But the role of second surgery is still debated, and the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) has developed a study in which second-look surgery is being performed in patients with residual local disease, following adjuvant chemotherapy before definitive radiation (COG ACNS0121). Fig. 8.1 A fourth ventricle ependymoma with peripontine infiltration and two seeding lesions on the right cerebellar cortex. Fig. 8.2 (A) Enhancement of the wide infiltration of the fourth ventricle floor. (B) Early postoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the patient. For many years radiotherapy has been established as an important modality in the subsequent treatment of intracranial ependymoma. Although local field radiation was used in the 1960s and 1970s, in 1975 extending the radiation field to include the whole brain was recommended based on the theoretical shedding of tumor cells into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Reports of similar failure rates in localized versus craniospinal radiation by the late 1980s led to the recommendation of a local radiation dose 4500 cGy (in 1.5–1.8 Gy fractions) for better local control.23,24,33–35 The method of increasing the chances of local tumor control in ependymoma using hyperfractionated radiotherapy (HFRT) has been adopted.12 In the Pediatric Oncology Group (POG) 9132 study, in 15 patients who had subtotal resection, a HFRT dose of 69.6 Gy given in 58 twice-daily fractions resulted in a 3-year event-free survival (EFS) rate of 52%.36 This result compared favorably with a similar historic group of patients treated with conventional fractionation that had a 5-year EFS rate of 27%.36 But this study was not able to demonstrate any clear benefit of HFRT in patients with GTR.36 Massimino et al12 reported on a series of 63 patients with ependymoma who were given HFRT for GTR or four courses of chemotherapy followed by HFRT for subtotal resection. However, they were not able to demonstrate a dramatically improved local control rate compared with the historical series, especially in patients with residual disease and anaplastic histology. New radiotherapy treatment techniques, such as conformal or stereotactic radiotherapy (SRT), have been developed to minimize the acute and long-term toxicities of radiotherapy. SRT uses highly focal, precise radiotherapy with the biologic advantages of fractionation.37–39 There are several reports with promising 3- to 5-year local control rates40 using SRT as a boost after conventional radiation therapy or for the treatment of recurrent ependymoma.40–46 It must be acknowledged, however, that there is no long-term follow-up on patients treated using this method, so that efficacy has not yet been determined. Conformal radiotherapy has also been used in 88 localized 1- to 21-year-old patients with ependymomas.47 The 3-year EFS rate was found to be ~75% in one series.47 Of note, 74 of 88 children in this preliminary report had GTRs.47 Twenty-four months after the initiation of conformal radiotherapy, no statistically significant change in the measures of neurocognitive effects (i.e., no more than +10 points from the normative mean for the appropriate age group) could be demonstrated.47 Current studies have also adopted a conformal approach for all patients older than 12 months of age. The American Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium study of children younger than 3 years of age uses intrathecal chemotherapy, or systemic chemotherapy, as the first-line treatment option and saves conformal radiotherapy for patients with higher-risk disease. COG also suggests conformal radiotherapy as a treatment option in a subgroup of patients older than 1 year of age with higher-risk localized ependymomas. With the help of ongoing trials, the benefits of conformal radiotherapy will be appreciated only if there is no increase in the rate of failure. Because acute and late toxicities should be within the predicted limits, these toxicity assessments need to be very carefully performed. Fig. 8.3 (A) An axial T1-weighted image showing a heterogeneous mass filling the fourth ventricle and left pontocerebellar angle. (B) Coronal T1-weighted image demonstrates the extent of the tumor to the C2 level. (C) Early postoperative study demonstrates the residual lesion. There are other studies reporting on EFS rates following GTRs suggesting that a subgroup of patients may benefit from deferral strategies, thus avoiding immediate postoperative radiotherapy.9,10,27,48–50 In these studies, 3 to 6 patients out of 6 to 20 patients9,10,27,51 have been reported to be long-term survivors who did not receive postoperative radiotherapy. These authors concluded that surgery alone was a reasonable option for totally resected, low-grade ependymomas. However, in a retrospective review with 45 patients, Rogers et al22 demonstrated that GTR and observation had an inferior 10-year overall survival rate when compared with GTR and irradiation (67% vs 83%, respectively; p>.05). Radiotherapy deferral strategies are also a part of the therapy plan for infants and young children. Earlier studies from the POG and CCG planned to use delayed irradiation in their infant protocols. In a later study by the Societé Française d’Oncologie Pédiatrique (SFOP) on infants and young children with ependymoma, the main aim was to avoid radio-therapy as first-line treatment. According to the updated results of the Baby POG I study, the 5-year survival rate was 25.7% in patients who had radiotherapy deferred for 2 years, and the 5-year survival rate was 63.3% in patients with 1-year radiotherapy deferral.16 The aforementioned difference in survival, as a result of deferred radiation, persisted even in children with a GTR and no metastases at diagnosis.16 These data suggest the sensitivity of ependymomas to chemotherapy while indicating the fact that radiation cannot be totally eliminated from treatment options. In the French Society of Pediatric Oncology Baby Protocol 90, infants were planned to be given radiotherapy only in case of progression under a multiagent chemotherapy regimen.52 With this strategy, radiation could be avoided in 23% of patients in this study.52 Additionally, the 5-year overall survival rate (52%) was found to be similar to that found in the Baby POG I study (63.3%).16 This finding demonstrates that some children with ependymoma can be cured without radiotherapy. CCG 9921,53 German Pediatric Brain Tumor Study clinical trials HIT-SKK 87 and 92,54 and the United Kingdom Children’s Study Group/International Society of Pediatric Oncology (UKCCSG/SIOP)55 prospective studies also deferred radiotherapy to progression/relapse with similar overall survival results: 59.0%, (5-year), 55.9% (3-year), and 60.0% (5-year), respectively. Nevertheless, the Headstart I and II studies with myeloablative chemotherapy and autologous hematopoietic stem cell rescue revealed an inferior 5-year survival rate of 38%,56 in comparison to the approach of multiagent chemotherapy with deferral of radiation to progression or relapse.52–55 In light of these studies, the deferral of irradiation to the time of first relapse could be recommended in children younger than 3 years old with radiologically proven GTR. However, because most patients with radiologically proven tumor residuum would show tumor progression in 1 year, such deferral of radiation might be lethal. Therefore, in children younger than 3 years old with residual tumor, conformal irradiation is strongly recommended with minimal deferral. Including the above-mentioned studies, there are several reviews that considered the role of chemotherapy in the management of ependymoma in children.52–55,57–59 However, all retrospective studies in the early 1980s failed to show a survival advantage.2,5,7,8,24,31 The only study using radiotherapy and chemotherapy with vincristine and lomustine versus radiotherapy in a randomized prospective manner was not able to demonstrate an improvement in the outcome of children with ependymoma.60 It could well be argued that the chemotherapy drugs used in this randomized study were not optimal. Needle et al61 reported a 5-year progression-free survival rate of 80% for patients older than 36 months of age with incompletely resected ependymoma who were treated with irradiation followed by carboplatin and vincristine alternating with ifosfamide and etoposide. Another CCG study (CCG 921), a prospective randomized trial that investigates the effect of lomustine, vincristine, and prednisone versus “eight in one” chemotherapy after radiotherapy in ependymoma patients older than 3 years of age, demonstrated similar survival rates (50%) for both chemotherapy arms.6 Multimodal treatment regimens used in the HIT 88/89/91 trial, consisting of adjuvant combined irradiation and chemotherapy (either ifosfamide, etoposide, methotrexate, cisplatin, or cytarabine and radiotherapy vs radiotherapy and methotrexate, cisplatin, or vincristine), were found to have increased 3-year survival rates to 75% in the treatment of anaplastic ependymomas in childhood.14 In some other reports, the 5-year survival rates for anaplastic versus nonanaplastic ependymomas have been found to range between 10 and 47% versus 45 and 87%, respectively.26,62–65 The current policy for children newly diagnosed with ependymoma is maximally feasible resection followed by local irradiation. Chemotherapy in the upfront setting is recommended in all patients younger than 3 years to delay or avoid radiotherapy. Chemotherapy is also recommended to decrease the rate of relapse in patients with GTR and increase survival rates in patients known to have a poor prognosis at the time of diagnosis. Thus, chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting is an option for patients in whom GTR could not be achieved and/or who have anaplastic ependymoma. In the recurrence setting, chemotherapy options are very limited, and they are palliative rather than curative. Reoperation of tumors that are surgically accessible, irradiation if not previously given, and salvage chemotherapy are the recommended management options in recurrent ependymomas.8,57,66 The role of STR for recurrence is under investigation.40,43,45 Because salvage chemotherapy is not curative, a variety of agents and schedules are also still under investigation.8,30,67–70 The agents to show mildly promising results have been cisplatin and etoposide.68–71 High-dose intensive chemotherapy with autologous bone marrow transplant rescue has also been investigated in the setting of recurrent ependymoma. Unfortunately, there was very little clinical response with a very high incidence of fatal toxicity.57,66 In conclusion, chemotherapy has very little effect in the setting of recurrent intracranial ependymoma. Ependymomas account for 8 to 14% of brain tumors in children. Approximately 85% of ependymomas present with localized disease. Gross total resection is the most important predictor of outcome. Conformal field radiotherapy is recommended as adjuvant therapy in most patients, especially in infants. Chemotherapy in the upfront setting is recommended in all infants to delay or avoid radiotherapy. The role of chemotherapy in achieving the optimal surgical outcome and/or rendering the patient free of visible residual disease is still under investigation. Chemotherapy is also recommended to decrease the rate of relapse in patients with GTR and increase survival rates in patients who are known to have poor prognosis at diagnosis. Thus, chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting is an option in patients in whom GTR could not be achieved or who have anaplastic ependymoma. Currently, the overall survival rate of all children with ependymoma is in the range of 39 to 69%. With approximately half of the patients eventually succumbing to disease, therapies aimed at improving survival are needed. Frequently, children who underwent posterior fossa irradiation for this tumor have relatively low intelligence quotients (IQs); therapeutic modifications such as conformal radiotherapy are aimed at decreasing the long-term neurologic morbidity. The development of new strategies to improve survival with minimum toxicity is the main focus of current studies. Intracranial ependymomas are the second most common malignant tumor of childhood. Despite a seemingly benign pathology and slow growth, their 5-year survival rates and long-term prognosis remain poor.72–79 Surgical resection is the initial treatment goal for these tumors.79–81 The majority of these tumors arise in the posterior fossa and are intimately associated with vital structures, making it difficult to attain a complete resection without significant morbidity. Even in the face of a GTR, the recurrence rate is significant, with various studies illustrating the need for adjuvant therapy.80,82,83 The decision of how to approach these tumors is currently controversial; radiotherapy is effective but not without risk of significant adverse effects. Chemotherapy has shown some promise in children who are too young for radio-therapy, but it is not curative.82,84 Therefore, treating physicians are left with the dilemma of deciding the use and timing of adjuvant therapy. Based on the current literature, we discuss the role and timing of adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy for children with intracranial ependymoma, as well as potential new targets for treatment of this disease. Brain tumors are the most common solid pediatric malignancy, with equal distribution in children up to 14 years of age. Intracranial ependymomas comprise ~2 to 14% of all pediatric brain tumors,81,85–87 with 60% diagnosed in children younger than 16 years.85,88 They are known to be the second most malignant tumor of children younger than 2 years of age, following medulloblastomas.84 Their presentation is mostly at a very young age, with a mean age of 24 to 72 months.89,90 They are equally distributed among boys and girls91 or with slight male predominance.90,92 A majority of these tumors are located infratentorially89–91

Surgical Resection

Prognosis and Treatment

Surgery

Radiotherapy

Chemotherapy

Recurrent Ependymoma

Conclusion

Surgical Resection with Adjuvant Therapy

Epidemiology

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree