complex partial

secondary generalized tonic–clonic

impaired

loss of consciousness

myoclonic

primary generalized tonic-clonic

not clinically impaired

loss of consciousness

CLASSIFICATION

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Epilepsy is defined as the tendency to have recurrent seizures. It affects 0.4 to 0.6% of the world’s population at any point in time, with a larger proportion of the general population (3-5%) having one or two non-recurrent isolated seizures throughout their life which do not develop into epilepsy. The global burden of epilepsy is estimated to be >50 millions of whom 80% live in low or middle income countries. Estimates of the frequency in Africa vary widely and studies from there have in the past suggested that active epilepsy is 2-3 times higher than in high income countries with a median frequency of 15/1000 (1.5%). However methodological difficulties make it difficult to compare most studies. A recent multicentre study from five sites in East Africa which reproduces strict methodology suggests a median frequency there of <0.5% which is similar to other parts of the world. The criteria used to diagnose active epilepsy were 2 or more unprovoked seizures during the previous 12 month period. There are two peak age groups when epilepsy occurs, the first one is in childhood and adolescence during which both birth related and genetic causes are typically found and the second peak occurs in older adults (>65 years) when there is usually an underlying structural cause in the brain.

AETIOLOGY

The aetiology is unknown or idiopathic in about two thirds of cases of epilepsy in Africa. This may in part be a function of under investigation due to lack of resources. Epilepsy has many causes and it is likely that genetic and historical causes account for a significant proportion of these. The main causes and their estimated frequencies in Africa are presented in Table 4.2. Genetic predisposition and brain injury are both known risk factors for epilepsy. Genetic factors are indicated by a positive family history of epilepsy. The underlying mechanisms of epilepsy are not known but a chronic pathological process as a result of tissue injury or some other common mechanisms seems likely in many cases. Pre and perinatal brain injuries arise largely as a result of hypoxia and hypoglycaemia because of intrauterine infections e.g. toxoplasmosis, rubella, HIV etc and because of poor obstetric care. Febrile convulsions (FC) as an infant or young child are a significant risk factor for scarring in the temporal lobe and epilepsy in later life.

Table 4.2 Main causes of epilepsy in Africa & their estimated frequency

| Cause | % of total | (range) |

| genetic | 40 | (6-60) |

| pre & perinatal | 20 | (1-36) |

| infections & febrile convulsions | 20 | (10-26) |

| cerebrovascular disease | 10 | (1-42) |

| head injury | 5 | (5-10) |

| brain tumour | 5 | (1-10) |

Ref Preux & Druet-Cabanac Lancet Neurol 2005; 4: 21-31

A history of previous CNS infection is a major risk factor for epilepsy in Africa. This is particularly the case for infants, children and younger adults. The main infections are meningitis, cerebral malaria, neurocysticercosis, encephalitis and brain abscess. Malaria is the most common cause of acute symptomatic seizures in children in malaria endemic parts of Africa. HIV is the most common cause in young adults. However it is important to remember that single seizures or those occurring during a febrile illness are not classified as epilepsy. Helminthic infections are an important cause of epilepsy in parts of Africa, in particular where free-range pig rearing is practised resulting in neurocysticercosis. Traumatic head injury mainly as a result of road traffic accidents and falls are increasingly a cause of epilepsy in young adults. Brain tumours and cerebrovascular disease account for a proportion of epilepsy mainly affecting adults.

Key points

- active epilepsy affects at least 0.5% of the population in Africa

- peak age groups affected are young children, teenagers & older adults

- cause is unknown in up to two thirds of cases

- genetic factors may account for a sizable proportion

- pre & perinatal brain injury & infections are main causes in young persons

- stroke, head injury and tumour are main causes in older age groups

COMMON FORMS OF SEIZURES

Generalized tonic-clonic seizure (GTCS)

This is the most common form of epilepsy in adults. Typically it involves consecutive clinical phases including tonic-clonic limb movements, loss of consciousness, frothing from the mouth, tongue biting, incontinence and post ictal confusion. If the origin of the seizure is focal as in secondary or partial onset epilepsy an aura may be present at the onset. In contrast there is no aura in primary or generalized onset epilepsy.

Aura phase

The clinical type of aura depends on the site of origin of the seizure. This phase typically lasts a few seconds or less and consists of a brief recurring stereotyped episode. The episode is characterized by an awareness of a familiar, typically epigastric feeling or the hallucination of a smell, taste but rarely hearing, usually coupled with automatisms if the origin is in the temporal lobe. If the origin is the parietal lobe, the episode is sensory, if in the frontal lobe it is motor and if in the occipital lobe it is visual. The aura phase of a partial onset GTCS may be forgotten because of retrograde amnesia.

Tonic phase

The tonic-clonic phase starts suddenly with loss of consciousness; the patient may make a loud noise or a cry and fall to the ground. There is a brief stiffening and extension of the body due to sustained tonic muscle contraction lasting about 10 seconds but which can last a minute.

During this tonic phase breathing stops and cyanosis may be recognised by observers. Urinary incontinence and less frequently faecal incontinence may occur at the end of this stage.

Clonic phase

The tonic phase is followed by the clonic phase characterized by repeated generalized convulsive muscle spasms. These are violent, sharp, rhythmical, powerful, jerky movements involving the limbs, head, jaw and trunk. The eyes roll back, the tongue may be bitten and frothing from the mouth may occur due to excess salivation as the result of excessive autonomic activity. This phase typically lasts a minute or two but may be more prolonged. The patient remains unconscious.

Coma phase

When the jerking has stopped normal breathing pattern returns but is shallow, the limbs are now flaccid and the patient remains unconscious and cannot be roused. The duration of unconsciousness ranges typically from about 5-20 minutes and reflects the extent and duration of the seizure. Then there is a gradual return of consciousness.

Post-ictal phase

On recovery of consciousness there may be confusion accompanied by a headache, drowsiness and typically sleepiness for a variable period sometimes lasting for up to several hours. Over the following days, there is usually some muscle stiffness and soreness and evidence of any injury sustained during the attack. Patients have retrograde amnesia for the seizure but may sometimes remember the aura phase before loss of consciousness.

Diagnostic features of a GTCS

- witnessed convulsion

- loss of consciousness

- tonic-clonic limb movements

- incontinence

- tongue biting

- postictal confusion

Absence seizures

This is the most common form of primary generalized onset epilepsy. It affects mainly children usually <10 yrs, (4-12 yrs) and is more common in girls. An attack occurs without warning. Usually parents or teachers note that the child suddenly stops what he or she is doing for a few seconds but does not fall down or convulse. The eyes remain open staring blankly ahead with occasionally blinking or eyelid fluttering. There is no response to an outside stimulus during the attack which ends as suddenly as it starts, usually with the child resuming activities unaware of what has happened. The attacks are brief lasting, typically between 5-15 seconds and can reoccur several times daily. The EEG shows a characteristic 2-3 per sec generalized symmetrical slow and spike wave discharges. Both attacks and EEG changes can be provoked by hyperventilation. The attacks respond well to treatment with low dose sodium valproate or ethosuximide. Children usually grow out of these attacks in their late teens but some few may develop into generalized onset TCS.

Diagnostic features of absence seizures

- mainly a childhood disorder & more common in girls

- stereotyped recurring episodes of loss of awareness or absences

- child goes blank, switches off for few seconds, stares ahead & may blink

- unresponsive during attack but does not convulse or fall down

Myoclonic seizures

These are another form of primary generalized onset seizures which are characterized by sudden, brief involuntary jerky limb movements lasting a few seconds. These seizures typically occur in young teenagers in the mornings after waking, with consciousness being preserved. Simple myoclonic jerks, which are generally benign, must be distinguished from juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME). JME consists of the triad of myoclonic jerks on waking occurring in all patients, generalized onset TCS in >90% of patients and typical day time absences in about one-third of patients. Absences may sometimes be an early feature, they begin in childhood and early teens and myoclonic jerks follow usually at around the age of 14-15 years. GTCS usually appears a few months after the onset of myoclonic jerks typically occurring shortly after waking. Occasionally JME may start or become clinically identified in adult life as ‘adult myoclonic epilepsy’. The EEG in JME shows typical polyspikes and slow wave discharges and may show photosensitivity. Treatment with low dose sodium valproate is usually very successful.

Diagnostic features of juvenile myoclonic epilepsy

- simple myoclonic jerks are benign and may not need treatment

- JME consists of morning myoclonic jerks, daytime absences & GTCS on waking

Partial onset seizures

If the site of electrical discharge is restricted to a focal area of the cortex in one cerebral hemisphere, then the patient will have partial onset seizures. The main causes include infections, infarcts, head injuries, tumours and hippocampal sclerosis, the latter due to frequent febrile convulsions in childhood. The clinical features depend on the site of the cortical focus and thus may be sensory or motor and involve alteration in consciousness. If there is no accompanying alteration of consciousness, then it is classified as a simple partial motor or sensory seizure. If there is alteration or clouding of consciousness, then it is a complex partial seizure. If the electrical spread becomes generalized, then it is classified as a secondary GTCS. Any patient presenting with new partial onset seizure disorder should be investigated with a brain scan to exclude a focal underlying cause.

Temporal Lobe epilepsy (TLE)

Complex partial seizures arise mainly in the temporal or frontal lobes. Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) is the commonest type of complex partial seizure disorder. The temporal lobe structures, particularly the hippocampus, are susceptible to injury during febrile convulsions, which may result in mesial temporal sclerosis (Fig. 4.6) and later TLE. The clinical features reflect the functions of the temporal lobe which include memory, speech, taste and smell. Seizures present as stereotyped episodes characterised by subjective experiences and movements. The subjective experiences include blank spells or absences, a sense of fear or déjà vu (an indescribably familiar feeling “that I have had this before”), or an inexplicable sensation rising up in the abdomen or chest. They may also include memories rushing back and hallucinations of smell, taste, hearing or images. To an observer the patient may appear confused and exhibit repeated stereotyped movements or automatisms including chewing and lip smacking. The attack typically lasts seconds to minutes depending on the extent and cause of the lesion. Attacks can be still more complex and if the electrical activity spreads to the rest of the brain then a GTCS may occur.

Diagnostic features of TLE

- stereotyped episodes lasting seconds

- déjà vu, depersonalization, rising sensation in epigastrium

- hallucination of mainly taste or smell

- movements, automatisms: lip smacking, chewing

- confusion and altered emotion

- may develop into a GTCS

Motor seizures (Jacksonian epilepsy)

This is a partial onset motor seizure disorder which occurs as a result of a focal lesion in the frontal lobe in or near the motor cortex. The convulsive movement begins typically in the corner of the mouth or in the index finger or big toe and then spreads slowly proximally to involve the leg, face, and hand (Jacksonian march) on the side of the body opposite the lesion. There may also be clonic movements of the head and eyes to the side opposite the lesion. The attack may develop into a secondary GTCS, and may infrequently result in a temporary limb paralysis (Todd’s paralysis).

Diagnostic features of focal motor seizures

- clonic movements begin focally in the corner of mouth or finger or toe

- spreads slowly to involve face, hand, arm, foot & leg on the same side

- may develop into a secondary GTCS

- may result in a temporary limb paralysis

Febrile convulsions

Febrile convulsions are seizures in children which typically occur between the ages of 3 months and 5 years as a result of fever from any cause. They are mostly GTCS in type and are a known risk factor for epilepsy in later life, and in particular TLE. They can cause damage to the temporal lobe that subsequently causes epilepsy. The scarring is mainly in the mesial temporal lobe and can be seen on MRI. The worldwide risk of epilepsy after childhood febrile convulsions is estimated to be 2-5%. In Africa this risk increases to around 10%, particularly after a history of repeated convulsions in malaria. Convulsions complicating malaria are one of the most common reasons for children presenting to clinics and hospitals in Africa. Convulsions occurring in uncomplicated malaria tend to be brief and non recurrent, whereas those occurring with complicated and cerebral malaria are more prolonged, multiple and recurrent, and carry a higher subsequent risk of epilepsy.

Clinical diagnosis

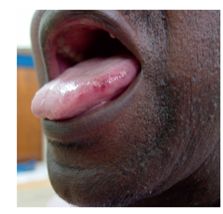

The diagnosis of epilepsy is mainly clinical. Epilepsy is difficult to diagnose and there is both under and over diagnosis of the condition. The first principle of diagnosis is to obtain a clear history from the patient and an eye-witnessed account of the episode. This involves the context in which the attack occurs, the details of the minutes or seconds leading up to and what happened during and after the attack. An attack of a GTCS is diagnostic if it includes a description of the convulsion, incontinence, tongue biting (Fig. 4.1) and post ictal confusion. All of these may not be present in any one patient. The description may alternatively be that of the typical vacant episodes of absence seizures or the aura of a partial onset seizure or of any another type of seizure disorder. If a patient cannot describe what happened, very often it is necessary to interview and record an eye-witnessed account or review a video of the attack if available.

Figure 4.1 Tongue biting

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree