41 External Versus Endoscopic Approaches for Skull Base Malignancies

Valerie J. Lund and David J. Howard

Introduction

Introduction

Malignant tumors in the nose and paranasal sinuses affecting the skull base present some of the most challenging problems in head and neck cancer. Because they are rare, it is difficult for any one practitioner or institution to accrue large numbers of patients and extensive expertise in their management. This is further complicated by their enormous histologic diversity, with every tissue type represented.

The majority of tumors are managed by surgery alone or in combination with radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy, but because patients have relatively mild symptoms at the start, they often present when the tumor is quite extensive and has invaded adjacent structures, such as the intracranial cavity and orbit. This may compromise the surgical approaches that can be undertaken with curative intention. Although endoscopic techniques (endoscopic sinus surgery [ESS]) are being increasingly employed, the results must be compared with those of established external surgery such as craniofacial resection (CFR). At present that comparison is difficult, as the number of patients, by tumor and length of follow-up, are all significantly less in the endoscopically treated group. This is particularly important when some sinonasal malignancies can recur many years later. However, some information is emerging as to the selection of patients, and this chapter discusses that information.

Which Tumor?

Which Tumor?

As previously mentioned, histologic diversity is the norm in this area, and each tumor has its own natural history that may influence the choice of procedure. Some, for example squamous cell carcinoma, are much more infiltrative than others, such as adenocarcinoma, which often has a well-defined plane of cleavage from normal tissue, making an endoscopic approach a better choice in the latter rather than the former.

In olfactory neuroblastoma (ON), we know that microscopic disease can be found in the olfactory bulbs and tracts even when it is not apparent on the most detailed preoperative imaging. This was the tumor par excellence for which CFR was devised, as it enabled complete resection of these areas, providing accurate staging for the first time.1 However, it is now technically possible to undertake this resection by an endonasal endoscopic approach, so this alone does not invalidate ESS for resection of ON.2–6

Interestingly, the accurate staging of disease extent provided by CFR led initially to radiotherapy being offered only to those with disease in the olfactory tract and bulbs, but in due course it became apparent that recurrence was higher in those individuals who did not receive radiotherapy (28% versus 4%), even though they had the smaller tumors.7 This has confirmed the need for combined therapy irrespective of tumor extent, and has given further reassurance to those undertaking ESS that they were not committing their patients to additional oncologic treatment; the addition treatment is required irrespective of the surgical procedure.

Another epithelial tumor with a fascinating natural history is adenoid cystic carcinoma, which is well known to follow perineural lymphatics, sometimes embolically spreading widely and placing patients at risk of primary and secondary recurrence throughout their lifetime. It could be argued that patients should undergo the most radical surgery possible, yet long-term studies have still shown recurrence many years or even decades later. Thus, a more tempered approach associated with lower morbidity, for example ESS, could be supported by the published research.6

Malignant melanoma of the sinonasal mucosa is also an unpredictable and capricious tumor, overwhelming some individuals in a matter of weeks or living in symbiosis for many years with others. Overall the largest cohort study demonstrated a depressing 5-year actuarial survival of 28%,8 and suggested that this occurred irrespective of surgical treatment, though patients undergoing craniofacial seemed to do particularly badly, which was not necessarily related to the extent of the disease. As a consequence, this tumor has been approached endoscopically for some time,4,6 occurring as it does in elderly individuals with other comorbidities.

Chondrosarcoma is an indolent but inexorable tumor that is difficult to extirpate whatever the approach. It can also be multifocal, which explains why recurrence may occur many years later in relatively distant parts of the skull base from the original lesion. Thus survival figures fall from 94% at 5 years to 37% at 15 years.9 This might seem a good reason to undertake a craniofacial approach, but one could equally argue that the improved magnification combined with the use of accurate high-speed drills actually supports ESS in accessible cases, especially when the orbital apex is involved, another area where ESS has shown itself to be of value.10

What Is the Site of the Tumor?

What Is the Site of the Tumor?

One of the most interesting aspects of ESS has been the appreciation of where tumors arise. A seemingly large tumor filling the nasal cavity and eroding the skull base on imaging may sometimes prove to originate from a small area of mucosa that can be readily resected. Endoscopic surgery has challenged some preconceptions regarding the usual site of origin.11

Combined computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offers a high degree of accuracy, distinguishing tumor from inflammation, fibrosis, and secretion,12 but it is only at surgery that this finding can be macroscopically confirmed and may often require frozen section corroboration. It therefore seems entirely reasonable, assuming local facilities allow, to have the patient sign a consent form for both ESS and CFR, and then begin operating endoscopically but with the option of converting to the external approach if required. With good patient selection, the number of occasions when this is required will remain very small.

How Extensive a Tumor?

How Extensive a Tumor?

When we talk about an endoscopic resection of a sinonasal malignancy affecting the skull base, we should be clear that this is not a debulking procedure but rather a genuine attempt at a curative resection. This means total excision of the tumor together with margins of normal tissue. The main advantage of CFR over the techniques that preceded it, such as lateral rhinotomy, is the ability to undertake an en-bloc resection of the ethmoids, including the cribriform niche and adjacent structures, as determined by the tumor extent.9 One of the criticisms leveled against ESS has been the fact that this is inevitably a piecemeal removal. However, in reality CFR is often piecemeal, and once the main specimen was removed, further clearance of the cavity was undertaken to ensure clear margins. Thus, the principle of en-bloc resection has been shown to be far less important than the complete removal of a tumor, given the specific constraints imposed by the complex anatomy in this area.

There are technical limitations to the areas that can be accessed by an entirely endoscopic approach, and these relate mainly to lateral extension over the roofs of the orbit. A rule of thumb is that pathology extending (or arising) lateral to a line drawn through the midpoint of the orbit cannot safely be reached via an endonasal endoscopic approach, and this would therefore need to be combined with or supplanted by an external procedure. Posteriorly and inferiorly, the endoscope has shown itself to be a reasonable alternative to external procedures, though again extension to involve the anterior and lateral wall of the maxillary sinus can be inaccessible in some individuals. This is particularly the case with squamous cell carcinoma of the maxilla, where infiltration beyond the bony confines is especially challenging. Achieving clear margins in these circumstances by an endoscopic approach alone can be technically impossible, and combined techniques such as an extended maxillectomy via a midfacial degloving together with endoscopic control may be employed.

It has been shown by many years of experience with endoscopic orbital decompression13 that significant portions of orbital periosteum can be removed endonasally, and our experience with preservation of the eye in CFR, as long as the tumor has not spread into the orbital contents, suggests that this approach can be safely undertaken in many patients who hitherto would have had their eye removed on oncologic grounds.14 Thus, involvement of the periosteum per se would not be a contraindication to endoscopic surgery, but should be determined by frozen section, and the endoscopic surgery might then need to be accompanied by orbital clearance in selected cases.

Superior extension through the skull base and dura and into brain is the subject of other chapters in this book. How aggressively a tumor is pursued will depend on many factors, not least the experience of the surgeons, the tumor type, and patient comorbidities. These limits remain a matter of debate. What constitutes the superior extent for one team may not be deemed so by another.

Dealing with Complications and Minimizing Morbidity

Dealing with Complications and Minimizing Morbidity

The main reasons for selecting an external approach over an endoscopic one are the morbidity associated with the procedures and the ability to control potential complications. The high long-term success rates for endoscopic repair of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks and skull base defects irrespective of the repair material used paved the way for extended endoscopic resection of neoplasms in this region.15,16 However, the resection of more and more extensive lesions resulted in defects that limited the utilization of some repair materials and led to the development of other techniques, including the pedicled septal flap, which increased the size of the dural defect that could be repaired endoscopically.17 Nonetheless, CSF leaks remain a potential problem and may necessitate a large piece of fascia lata or a pericranial flap, best encompassed via an external approach.

The complication that is most difficult to deal with endoscopically is bleeding. This may be anticipated because of the tumor type, for example, olfactory neuroblastomas, malignant melanomas, or involvement of major vessels, and in selected cases may benefit from preoperative embolization. However, in the majority of cases CFR provides greater access if severe bleeding occurs, and for many surgeons concerns about bleeding from the internal carotid may prompt the use of this approach.18 Nonetheless, some centers have published strategies for dealing with this eventuality endoscopically, so this may come to be regarded as a relative rather than an absolute contraindication to ESS.19

Both external and endoscopic procedures themselves can be associated with complications, which in theory are the same but in practice are significantly less using ESS.4,6 Some series of CFR have shown very low mortality and morbidity,9,20 but overall ESS intrinsically is less traumatic even though the amount of tissue removed is comparable, as there is less collateral damage resulting in shorter operating time and hospital stay.4,21 Nonetheless, we should be very aware of the prognostic factors that determine outcome in these patients for whom the first treatment is the best treatment. Multivariate analyses consistently show that involvement of the dura and brain, involvement of the orbit, and the type of malignancy are the most important factors when large prospective long-term CFR series have been analyzed, and we must therefore choose the approach that best allows us to deal with them.20 If both ESS and an external approach fulfill these criteria, then either may be chosen, but if we are in any doubt, we should be able to make the transition from one to another, combining conventional craniotomy with endoscopic resection from below.22–24

Adjunctive Medical Oncology

Adjunctive Medical Oncology

Chemoradiation is often given to patients with sinonasal malignancy and, depending on the center, may be given before or after surgery. It has been our experience that it is advisable to delay this treatment when it is used after a craniofacial approach to minimize problems with the skull base repair.9 This may not be a constraint with ESS if the area of skull base repair is commensurately smaller. Whether this makes a difference to prognosis is unknown.

Every 4 months for first 2 years, then every 6 months thereafter depending on histology: Endoscopic examination under anesthesia Magnetic resonance imaging: coronal, axial, and sagittal T1-weighted sequences, pre- and postgadolinium–diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA), and axial T2-weighted sequences |

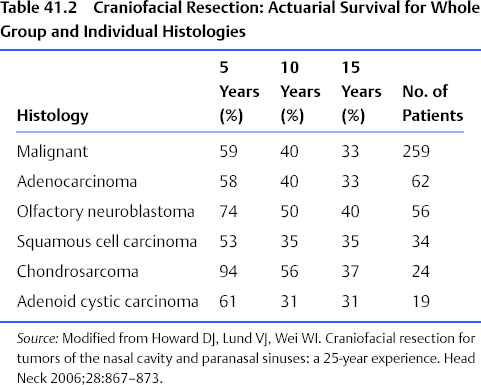

Source: Modified from Howard DJ, Lund VJ, Wei WI. Craniofacial resection for tumors of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses: a 25-year experience. Head Neck 2006;28:867–873. |

Postoperative Follow-Up

Postoperative Follow-Up

Descriptions of the respective techniques are beyond the scope of this chapter and are described in detail elsewhere.25 However, in all cases, irrespective of the surgical approach, patients must be submitted to rigorous long-term follow-up to ensure that residual or recurrent disease is found early. This may allow endoscopic resection even after CFR. Patients should be available for regular endoscopic examination in an outpatient setting, and posttherapy imaging, usually multiplanar contrast-enhanced MRI, combined with formal examination under anesthesia as indicated by the tumor type and imaging findings. Various protocols have been devised; an example of the one used by the authors is shown in Table 41.1.

Outcomes

Outcomes

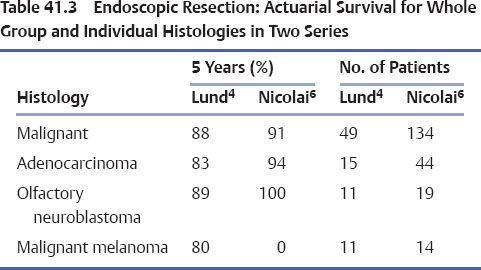

Craniofacial resection has dramatically improved the outcome for malignant sinonasal tumors affecting the anterior skull base, doubling the survival in many cases (Tables 41.2 and 41.3). However, late recurrence is a feature of these tumors, emphasizing the fallibility of 5-year actuarial survival in predicting cure. Indeed with some tumors (e.g., adenoid cystic carcinoma), the patient will most probably die from the disease unless some other event intervenes. This, together with the rarity, range, and different extents of tumors, makes a direct comparison with endoscopic techniques difficult at present but speaks to the need for collaborative collection of accurate data.26 Nonetheless, as indicated, there are an increasing number of patients who can be equally well treated with a curative endoscopic resection.2–6,21 Ultimately the issue is not external versus endoscopic techniques but rather a strategy based on many factors, the most important of which is completely removing the tumor.

References

12. Madani G, Beale TJ, Lund VJ. Imaging of sinonasal tumors. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2009;30:25–38

15. Lund VJ. Endoscopic management of cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Am J Rhinol 2002;16:17–23

< div class='tao-gold-member'>