Chapter 79 Far Lateral Approach and Transcondylar and Supracondylar Extensions for Aneurysms of the Vertebrobasilar Junction

Lesions of the anterior and anterolateral brain stem present special challenges to the neurologic surgeon. Unlike the posterior surface of the brain stem, the anterior surface is buried deep within several vital structures precluding easy anterior access. For this reason, lateral approaches have been proposed to access the anterolateral surface of the lower brain stem from a posterior incision. Heros1 first described extensive removal of the lateral foramen magnum up to the condyle to approach these lesions. Later authors advocated progressive drilling of bony structures lateral to the foramen magnum such as the occipital condyle, jugular tubercle, atlanto-occipital joint, and mastoid. As each lateral structure is removed, the angle of approach to the anterolateral surface of the brain stem is increased and the surgical corridor widened. However, morbidity from damage to the vertebral artery (VA) and cranial nerves as well as frank instability of the craniocervical junction is also increased with each structure removed.

Anatomy

Muscular Anatomy

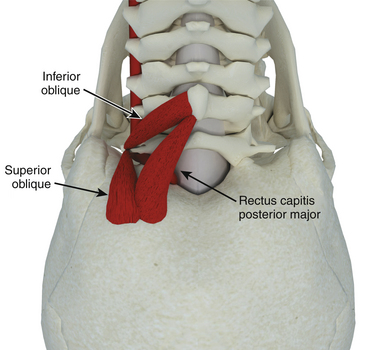

Despite our belief that separation of each individual muscle layer is unnecessary for the far lateral approach, an understanding of the upper cervical muscles and their attachments is an important aspect of performing the far lateral approach safely. The key to the exposure of the far lateral approach lies in the identification and preservation of the extradural vertebral artery, which lies within a triangle of muscles referred to as the suboccipital triangle (Fig. 79-1).

Extradural Anatomy

Three specific points regarding the extradural VA deserve mention. First, as it courses medially in the sulcus arteriosus, it may loop cranially near the occipital bone. This must be kept in mind during the muscular stage of the exposure—it is surprisingly easy to inadvertently bovie into the artery when attempting to separate the last bit of cervical musculature off the suboccipital region. Second, while the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) usually arises from the VA intradurally, in approximately 5% to 20%2 of specimens it arises extradurally and can be confused with a muscular branch off the VA. Third, the VA sits in a venous plexus as it courses in the sulcus arteriosus, which often leads to troublesome bleeding if one chooses to expose it.

An interesting anatomic study quantified the benefit of removing these two structures in terms of visualization and surgical freedom.3 The authors found that removing the occipital condyle up to the hypoglossal canal resulted in a mild improvement (21% to 28%) in visualization but a much larger improvement (18% to 40%) in surgical freedom (ability to manipulate surgical instruments within that space). Resection of the jugular tubercle on the other hand, had the opposite effect with a dramatic increase (28% to 71%) in visualization but only a modest (40% to 52%) increase in surgical freedom. This emphasizes the role the occipital condyle plays in narrowing the surgical spatial cone through which instruments are manipulated.

Surgical Technique

Various positions can be used including supine with the head rotated, lateral or half-lateral decubitus, and a three-quarter prone or park-bench position. At our institution we prefer a straight lateral position. The patient is placed on the operating table with the side of the lesion placed upward. The dependant arm hangs off the bed and is cradled in a padded sling between the table edge and the Mayfield head holder. The head is then secured in a three-pin Mayfield head clamp. Pin placement is crucial if an occipital artery bypass is contemplated as it may hinder the procedure if placed improperly. The pins are placed so that the single pin is 2 cm superior and anterior to the ear pinna ipsilateral to the lesion. The paired pins are positioned so that the posterior pin is 2 cm above the contralateral ear pinna. The head is positioned with three or four movements:

1. Flexion in the anteroposterior plane with slight distraction until the chin is two finger breadths from the clavicle uncovers the suboccipital region.

2. Contralateral bending (approximately 30 degrees) increases the surgical space between the ipsilateral shoulder and the suboccipital region.

3. Upward translation partially and subtly subluxes the ipsilateral atlanto-occipital joint and facilitates possible condylar drilling.

4. Contralateral head rotation in order to bring the ipsilateral side uppermost in the surgical field. Although some authors have advocated this manuever,4 the senior author (RCH) believes that this maneuver is not advisable as it results in rotation of the ventral surface of the brain stem and thus the vertebrobasilar junction away from the surgeon. In fact, upon completion of the bony drilling and opening of the dura, we routinely rotate the operating table toward the surgeon to allow a tangential view of the ventral brain stem. The operating table is placed in slight reverse Trendelenberg so as to position the patient’s head above the level of the heart to reduce cerebral venous congestion. The patient’s superior shoulder is retracted towards the patient’s feet using adhesive tape to keep the cervical-suboccipital angle open (Fig. 79-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree