(1)

Hand Surgery Department of Clinical Sciences, Malmö Lund University Skäne University Hospital, Malmö, Sweden

Abstract

Three hundred and seventy-five million years ago, many different types of big fish lived in the sea. Gradually, some of them began approaching shallow water close to land. It became advantageous for these fishes to be able to support themselves on the seabed with their fins so they could raise their heads above the water’s surface in an amphibian-like way. In this transitional phase between life in the water and life on land, the fins of some fish species showed an obvious development towards an arm and a hand. The Tiktaalik, discovered on Ellesmere Island in northern Canada and dating back to about 375 million years ago, has been regarded as a missing link between fish and land animals, showing a first hint of a human hand in its fin.

We tend to take our hands for granted, always present and always prepared to intuitively translate our wishes and intentions into movement – whether turning pages in a newspaper, peeling a freshly boiled egg, shaking hands with a good friend or unlocking the front door when we return home from work. The hand is a fine motor instrument with great precision, but it is also a delicate organ with highly advanced sensory functions.

When in the evolutionary process can we first distinguish a preliminary draft of something that would much later result in a human hand? To find an answer, we have to go back several hundred million years, to a period of the earth’s development when no land animals yet existed.

About 375 million years ago when the earth was mainly covered with water, the remaining land was swampy, marshy, and filled with mangrove-like trees. Many different species of big fish lived in the sea, some of them with swim bladders that would later develop into lungs [1]. Thanks to rich vegetation, with plants and trees growing close to the seashores, the water became increasingly nutrient-rich, and some fish species began approaching the shallow water close to the mainland. When that happened, it became advantageous for them to be able to support themselves on the seabed with their fins so they could raise their heads above the surface of the water.

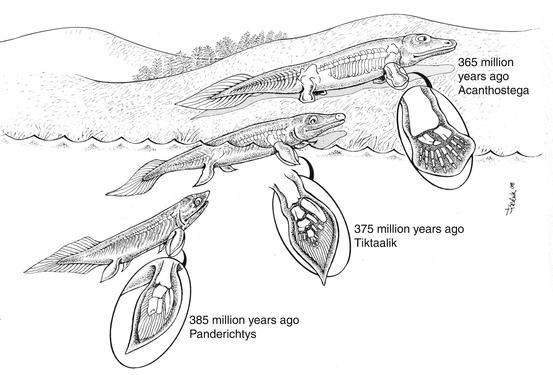

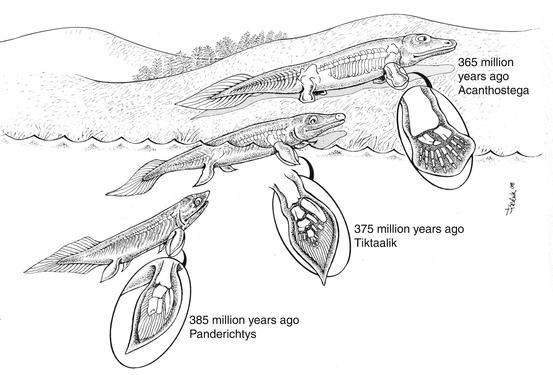

In this transitional phase between life in the water and life on land, the fins of some fish species showed an obvious development towards an arm and a hand (Fig. 1.1). Perhaps can we regard these very early events as the first hints of a human hand and, accordingly, the first step towards a future human civilisation several hundred million years later.

Fig. 1.1

Several hundred million years ago, when the earth’s landmass consisted of marshes and swamps, many big fishes began a slow adaptation process towards life on land, involving the transformation of fins to extremities. One such example is Tiktaalik, representing a transitional phase between the fish Panderichthys and the tetrapod Acanthostega. The fins of Tiktaalik contained skeletal details reminiscent of a human arm/hand with an upper arm bone, two forearm bones and pre-stages of wrist and finger bones (Illustration: Fredrik Johansson)

A Fish Approaching Land

About 385 million years ago, at the end of the Devonian Period, several big fishes went through an adaptation process towards a land-based life, and several fish species with an amphibian-like appearance arose [2, 3]. One example is the Panderichthys, an alligator-like fish about 1 m long with eyes on top of a flattened head. Its fins had developed armlike skeletal structures with a shoulder blade (scapula), an upper arm bone corresponding to a humerus and two forearm bones corresponding to the ulna and radius.

However, it was still a fin, comprised of about 20 fine radial-like structures arranged along the periphery like a fan, giving it stability. The Panderichthys’ head was firmly fixed to the body and could not be moved separately. The Panderichthys is considered to be the last fish in the development towards land animals with four extremities, the so-called tetrapods [4].

In 1931, a spectacular find was made on Ymer Island in Greenland. On the slopes of the Celsius mountain, a Danish expedition, led by the Swede Gunnar Säve-Söderbergh, found remnants of a 365 million-year-old fishlike skeleton showing four obvious extremity-like components. The specimen, named Ichthyostega, is still preserved in the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm together with another closely related fossil, Acanthostega, from the same area. The Acanthostega has four extremities and was clearly adapted for life on land. The two front extremities had well-developed arm bones with obvious finger structures; however, interestingly, there were eight digits on each of these rudimentary limbs. The extremities were stiff and nonmobile, more adapted for swimming or dragging itself along the seabed than for moving on land. The Acanthostega probably spent most of the time in the water even if it might have made short excursions up on land.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree