Chapter 149 Fungal Infections of the Central Nervous System

Surgical infections of the nervous system present with protean clinical manifestations, difficult diagnostic dilemmas, and special therapeutic challenges. The nervous system may be infected by (from most to least common) bacterial, viral, parasitic–protozoal, and fungal organisms. Fungi are common in our environment, but only a few are pathogenic. In general, fungi are organisms of low pathogenicity, emerging as opportunistic organisms thriving in a compromised host. Fungal infection may involve craniospinal axis, meningeal coverings, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), brain, and spinal cord separately or in various combinations. Although fungal infections (mycoses) of the CNS are uncommon, the spectrum of neurologic manifestations of fungal infections in the CNS is of particular importance to the neurosurgeons.1–18 Therefore, the diagnosis of CNS fungal infection should be considered in appropriate clinical settings.

Historical Aspects

Fungal infections have been recognized since early times, but CNS fungal infections have mainly been recognized since the 19th century. Common fungal infections are relatively benign; serious ones are rare. There are morphologic similarities in various fungi, which create difficulty in differentiating these structurally complex forms.1–19 Generally, Hippocrates is credited with the first description of candidiasis in his book Epidemics, in which he described white patches in the oral cavity of a debilitated patient. The fungal etiology of these thrushes was established in 1840s by Berg and Bennett. Zenkar described the first patient with intracerebral candidiasis, who died in 1861. Smith and Sano were the first to report a case of Candida meningitis in 1933.16,19 Various postmortem studies have established that candidiasis is a more common CNS fungal infection than aspergillosis, zygomycosis, or cryptococcosis.

In 1792 in his book, Micheli (a priest and botanist) described Aspergillus to refer to the nine species of fungi that resembled aspergillum, a perforated globe frequently used to sprinkle holy water during religious ceremonies. In 1856, Virchow had published the first complete microscopic description of Aspergillus. However, it was Pope in 1897 who reported the first case of rhino-orbitocerebral aspergillosis and of cerebral aspergillosis in man due to extension of fungal infection from sphenoid sinusitis.2,14,17 The first case of human zygomycetes was described by Kurchenmeister in 1855 that isolated nonseptate hyphae from a cancerous lung, and Gregory in 1943 described rhinocerebral zygomycosis9 in detail, with presentation of three cases of the disease.3,11,12

In 1905, Van Horseman probably first demonstrated Cryptococcus in spinal fluid, although cerebral Cryptococcus was initially described by Buses in 1894.9 Gonyea19 reported on three patients of blast mycosis meningitis in 1978 without extracranial infection, and Opus was first to report a coccidioidal brain lesion in 1905.3 In 1952, Binford published a case of cerebral abscess due to Cladosporium.17 Histoplasmosis was first described by Darling in 1906 in a patient with disseminated granulomatous infection. Histiocytes were studded with Histoplasma capsulatum.20

Gilchrist described blastomycosis in 1894 and successfully grew the organism in culture.21 Coccidioidomycosis was described by Dosadas and Wernicke in 1892. However, Ophuls was the first to describe coccidioidal meningitis in 1905. Paracoccidioidomycosis was first described in 1908 by Lutz in Brazil. In 1888, Nocard described acid-fast aerobic actinomycetes in cattle, which was called Nocardia farcinica by Trevisan in 1889, and Eppinger in 1891 reported the first case of metastatic (from lung) cerebral nocardiosis.22,23

Antifungal chemotherapy began in 1903 with the successful use of potassium iodide for the treatment of cutaneous–subcutaneous sporotrichosis.22 The first useful polyene drug, nystatin (1953) and second useful polyene drug, amphotericin-B (1956) were introduced for mucosal and systemic mycoses, respectively.8–28 Amphotericin-B remains the standard against which other antifungal drugs are compared.22,27 Although, fungal infections in the CNS have been recognized for more than 100 years, until the antifungal agent amphotericin-B was discovered, fungal infections were regarded as nearly impossible to treat effectively.

Over time, other important antifungal drugs were reported following amphotericin-B, that is, flucytosine (5-fluorocytosine, 1964) and azole drugs (1970s): miconazole (1978), ketoconazole (1981), fluconazole (1990), and itraconazole (1992).22–34 In the last two decades, some potentially beneficial antifungal drugs have been discovered and introduced for their appropriate use. To reduce the toxicity of amphotericin-B, liposomal amphotericin-B, or its combination with lipids, was initially introduced,25,28,33 followed by triazoles (voriconazole, posaconazole, etc.) and, more recently, echinocandins (anidulafungin, caspofungin, micafungin, etc.). These medications are increasingly used in various combinations in seriously ill patients with invasive mycoses with favorable results and giving some hope in improving our results in the future.

Classification and Epidemiology

The phylum Thallophyta includes certain plants (cells that contain chlorophyll and therefore synthesize their own food) and fungi (organisms devoid of chlorophyll that are therefore saprophytic).9 Fungi are ubiquitous microorganisms that may be unicellular or filamentous. The latter produces branching hyphae, which grow only at the apex. The enzymes produced by the complex fungal cell wall break down proteins, carbohydrates, and other macromolecules. The resultant micromolecules are taken up by the fungal cells or hyphae to maintain their life processes.18 One million known fungal species exist in the nature, and around 200 species are known to be pathogenic to humans. Only about 20 fungal species produce invasive systemic infections, including CNS disorders.

Fungi are classified as follows: pseudomycetes/yeasts (Blastomyces, Candida, Coccidioides, Cryptococcus, Histoplasma, Paracoccidioides, and Sporotrichum), septate mycetes (Aspergillus, Cephalosporium, Cladosporium, Diplorhinotrichum, Hormodendrum, Paecilomyces, and Penicillium), and nonseptate mycetes (Absidia, Basidiobolus, Cunninghamella, Mortierella, Mucor, and Rhizopus).3,6,9,18

Prevalence, Dispersion, and Infection

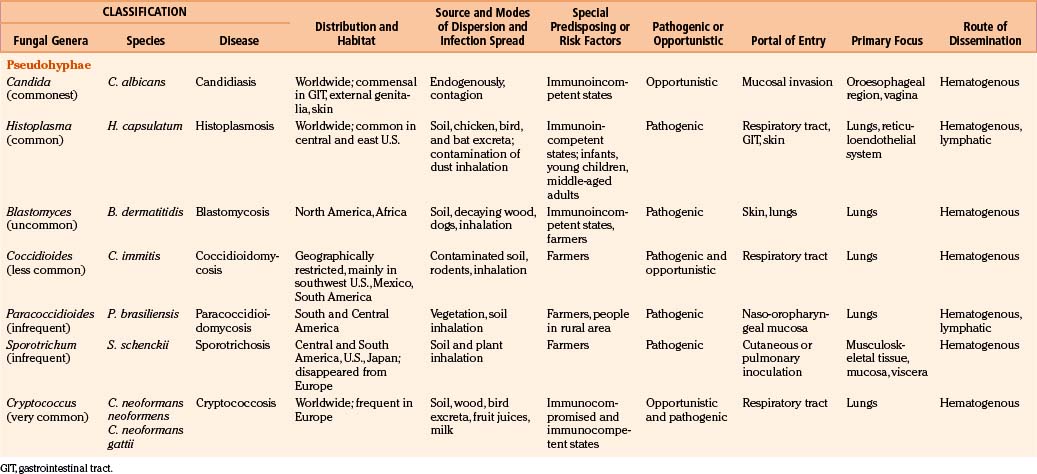

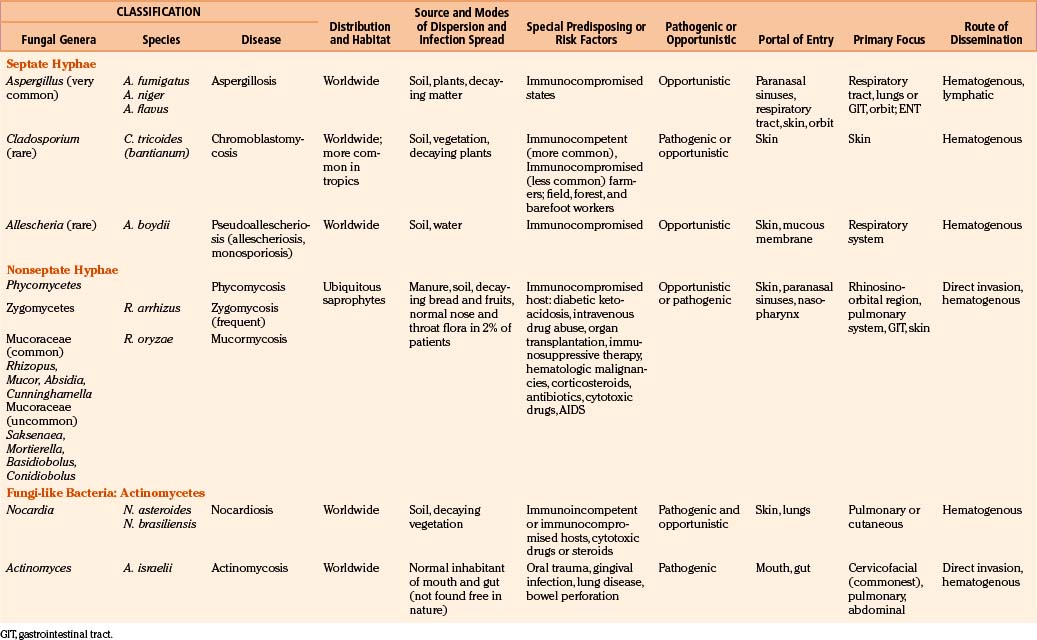

In general, fungi are ubiquitous, nontransmissible from patient to patient, and rarely pathogenic to humans (Table 149-1). Fungal infections are not notifiable diseases, and precise information on their prevalence throughout the world is not available.3,6,18 However, most fungal infections are not geographically restricted. Fungi are abundant in the environment, including soil and vegetation. Little moisture and organic matter, such as dead plant or animal material, are all that are required for their growth. They have long been recognized as agents of spoilage and destruction. Although only a few mycotic diseases are exclusively tropical, some of them are predominant in regions where they find ideal climatic conditions for their development. In addition, poverty, poor working conditions, and the habit of walking barefoot provide additional conditions for the spread of mycoses.

Fungal spores are common in the air, which is the medium for their dispersion. Man acquires infection by inhalation of airborne spores, implantation of viable fungal elements through the cutaneous puncture wounds, ingestion, and contagion from infected animals or from organisms already present as commensals. Most human mycoses are confined to lining surfaces, such as the skin, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, and female genitalia, and do not involve deep parenchymal organs.19 Usually, the inhaled aerosolized fungi initiate a primary mycotic infection in the lungs or paranasal sinuses, which is usually self-limiting but may spread to the other organs.

Fungal infections in the brain are invariably secondary to infections elsewhere in the body; however, the site of entry may remain unrecognized, and cases have been reported in which the only evidence of fungal infection was in the CNS.19,35,36

Routes of Dissemination

Candida may be endogenous, inhibiting the digestive tract and vagina.37–64 Aspergilli65–87 and zygomycetes88–98 colonize and infect the structures adjacent to the cranial cavity, such as the sinuses, nasopharynx, middle ear cavities, and mastoid air cells. Histoplasmosis99–104 and cryptococcosis105–113 spread by the blood stream to the CNS, meninges, or parameningeal structures from a primary, often subclinical pulmonary focus; only rarely does the organism reach the CNS following direct inoculation after trauma, surgery, or lumbar puncture. Colonization of artificial prosthesis, implants, and other devices—such as intravenous or arterial lines, peritoneal dialysis catheters, or ventriculoperitoneal, ventriculoatrial, or external ventricular drainage systems—by Candida is becoming increasingly common.16,18,35,61,109–116

Host Susceptibility and Fungal Virulence

All fungi may be considered potential pathogens when normal defenses are compromised (Table 149-1). The establishment of infection depends on the host defenses, route of fungal exposure, and size of the inoculum, as well as the virulence of the organism. The presentation for a given organism is fairly consistent, regardless of the underlying host immune status. Nevertheless, the immune status of the host preselects certain organisms. Fungi, which produce systemic infection, fall into two major groups: pathogenic fungi and opportunistic fungi.2–19 In general, pathogenic fungi infect both normal hosts and individuals with reduced host defenses, whereas opportunistic fungi infect mainly immunocompromised patients. Pathogenic fungi are usually yeasts capable of establishing life-threatening CNS mycotic infections: coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, sporotrichosis, and paracoccidioidomycosis. Cryptococcosis is found in equal numbers of otherwise healthy people and immunosuppressed patients. Many opportunistic fungal infections develop almost exclusively in the immunosuppressed population. Septate mycetes (aspergilli), nonseptate mycetes (zygomycetes), and yeasts (Cryptococcus and Candida mycetes) are mainly opportunistic fungi. However, the distinction between pathogenic and opportunistic fungi is not absolute.

Pathogenesis

Fungi grow profoundly in environments with an abundance of organic matter and water.2,4–9,11,23,37–45,49–51 Enzymes produced by the fungal cell wall act on the organic matter and break down their proteins, carbohydrates, and other macromolecules into micromolecules, which are then easily used by the fungi to maintain their life processes. Generally, the brain and spinal cord are regarded as immunologically privileged sites. The brain has a specialized, relatively impermeable blood–brain barrier (BBB), and its surrounding subarachnoid spaces have effective meningeal barriers. These highly vascular structures provide effective resistance to fungal infections. For immune surveillance, mainly activated T-lymphocytes are usually permitted across the BBB in normal individual. However, in immunocompromised states, these anatomic and functional barriers are easily overcome by common opportunistic and/or pathogenic fungi to produce clinical manifestations. Fungal infections of the CNS also evoke humoral and cellular responses like those in bacterial infections to enable the host to eliminate the pathogen. Activation of the resident brain cells by fungi combined with relative expression of immune-enhancing and immune-suppressing cytokines and chemokines may play a determinant role and partially explain the immunopathogenesis of CNS fungal infections. Activated resident brain cells such as microglia, astrocytes, and endothelial cells express major histocompatibility complex class I and II molecules and therefore act as antigen-presenting cells. In addition, they express complement (C) receptors and produce cytokines, chemokines, and molecules with antifungal activity such as nitric oxide. They are also capable of phagocytosis. Microglia, acting as antigen-presenting cells, stimulate T-cell proliferation and cytokine secretion, which in turn stimulate these microglial cells to ingest and more effectively kill invading fungi. The C system is a key component of innate immune system, playing a central role in host defenses against pathogens. It is also a powerful drive to initiate inflammation and if unregulated can result in pathologic changes that lead to severe tissue damage. It is generally accepted that the C system is essential to mediate cytolysis of fungi. Furthermore, it is well known that C receptors expressed by activated microglial cells are important to mediate phagocytosis. Immunopathogenesis of CNS fungal infections in humans is not completely understood. The exploration of the genomic sequence of most fungal pathogens can help better understand the pathogenesis, virulence, and immune response of host defenses against these pathogens. Further studies in these areas will advance our understanding about CNS mycoses: Fungi produce diseases due to their allergenicity, toxigenicity, pathogenicity, and neurotoxicity, but CNS mycoses are essentially due to serious infective processes.18

CNS fungal infections have been on the increase in the last decade due to many factors, such as the growing number of immunocompromised patients who survive long periods; widespread use of immunosuppressive drugs; a large aging population with an increased number of malignancies; lymphoma and leukemia, especially when associated with leucopenia/granulocytopenia (Candida and Aspergillus); the spread of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS); poorly controlled diabetes mellitus (zygomycosis); and renal and other transplant patients requiring prolonged immunosuppression.3,6,9,12,18,19

Clinicopathologic Syndromes

Fungi infecting the CNS are found in three major morphologic forms with distinct clinicopathologic syndromes.6,9,12 The first, leptomeningitis (acute and chronic), is mainly produced by small pure yeasts (pseudomycetes) up to 20 μm in diameter (blastomycosis, cryptococcosis, and histoplasmosis). Because of their small size, these fungi gain access to the cerebral microcirculation, from which they infect the subarachnoid spaces. Next, cerebral abscesses are produced by larger pseudomycetes (candidiasis). These intermediate-sized fungi occlude cerebral arterioles and result in adjacent tissue necrosis that rapidly converts to microabscesses. Persistence of infection causes granulomatous inflammatory reaction in adjacent leptomeninges, neural parenchyma, or both. Finally, very large branched septate (aspergillosis) or nonseptate mycetes (zygomycosis) produce cerebral infarction. These fungi mainly obstruct the intermediate-sized and large cerebral arteries and invade the vessel wall, causing cerebral arterial thrombosis and associated cerebral infarction. The evolving hemorrhagic cerebral infarcts may convert into septic infarcts with associated cerebritis and abscesses.

Clinical Spectrum of CNS Fungal Infections

In fungal infections (mycoses), the organism can invade tissues without an underlying predisposition (pathogenic fungi), but many common systemic mycoses affect patients with abnormalities in structure, immunity, and metabolism (opportunistic fungi) (Table 149-2).

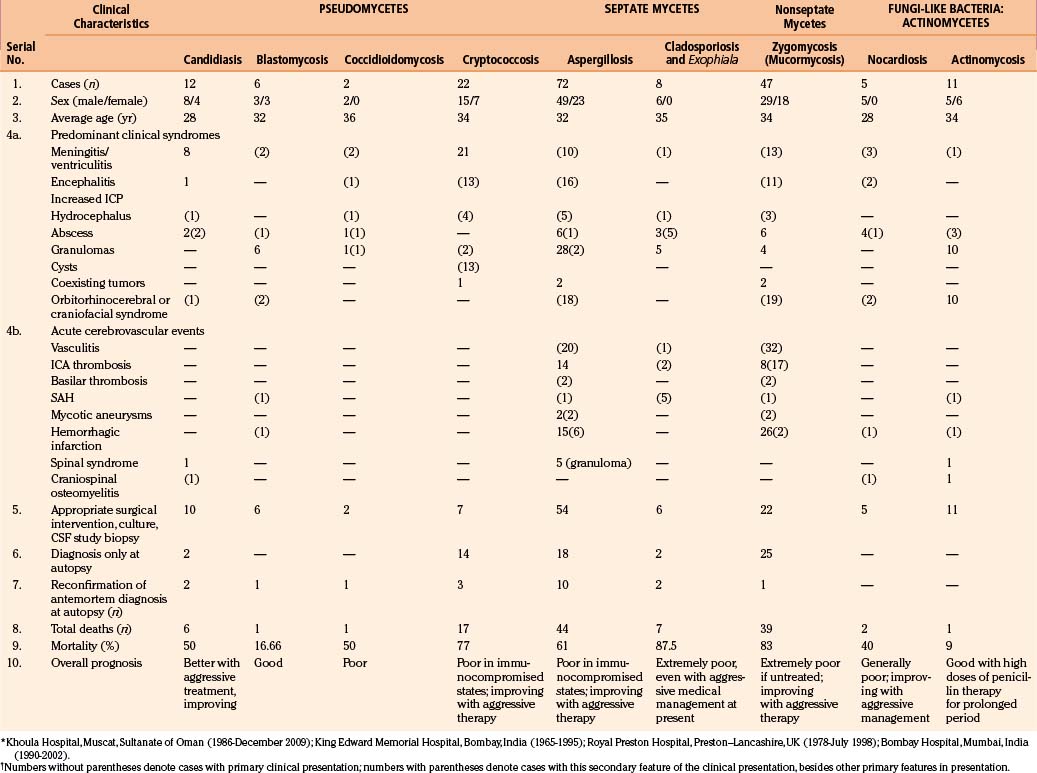

The involvement of the CNS in fungal infection may be disseminated (cryptococcosis and coccidioidomycosis), focal (aspergillosis), or multifocal (candidiasis). Due to their protean manifestations in various clinical settings, CNS fungal infections present a difficult diagnostic and therapeutic challenge to neurosurgeons. Because these organisms are uncommon and often manifest indolently, diagnosis tends to be difficult and at times missed. Expected mortality rates are high under the best circumstances, even with rapid diagnosis, aggressive medical therapy, and operative approach. The clinicopathologic findings and results of a combined series of verified cases of fungal and fungi-like bacterial (pathologic and actinomycetic) infections of the nervous system are presented from major institutions where the principal author (Sharma) either had worked (King Edward Memorial Hospital, Bombay, India, and Royal Preston Hospital, Preston–Lancashire, UK) or is working (Khoula Hospital, Muscat, Oman) or from major institutions associated with other authors (Table 149-3).

Pseudomycetes Causing Infections of the Nervous System

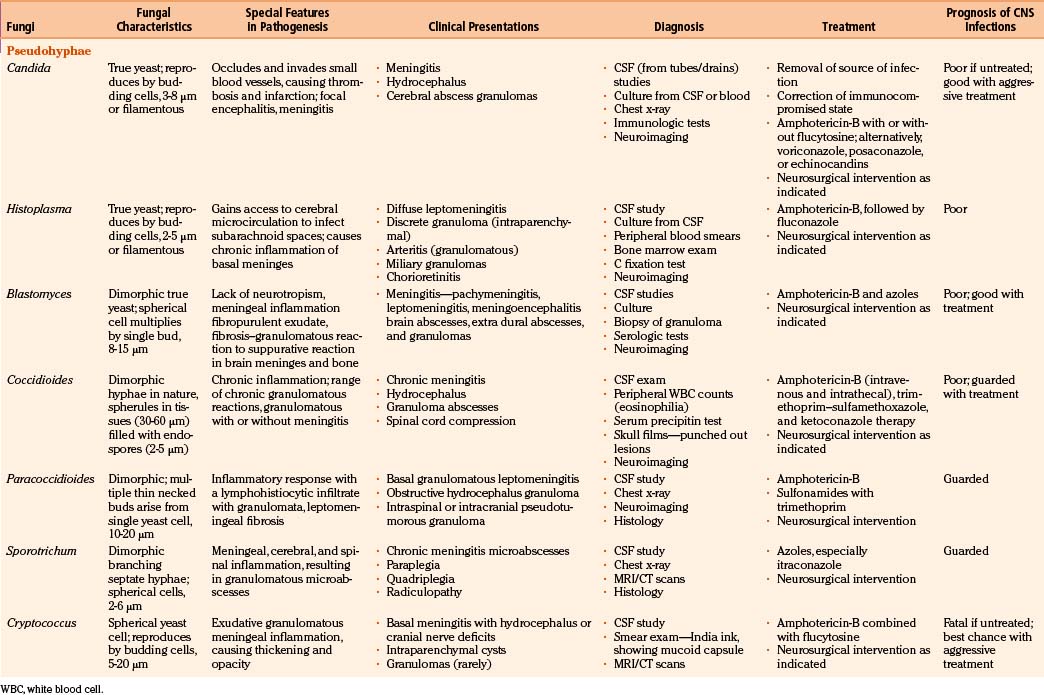

Candidiasis

As a complication of disseminated candidiasis, the brain parenchyma and meninges get involved, with fatal outcome in many patients. In autopsy studies, cerebral mycosis was noted to be most commonly caused by candidiasis.3–19

Candidiasis commonly presents as thrush in the oral cavity or vagina; less commonly, skin and visceral organs are involved.51 Candida organisms are found worldwide. Their pseudohyphae are associated with 2- to 3-μm spherical or oval blastospores. Candidiasis arises when the balance between Candida species and the host is altered in favor of the yeast.64 The C. albicans originally infects the gastrointestinal tract (oral cavity and esophagus) after the antibiotic treatment, then invades submucosal blood vessels, and finally disseminates hematogenously to the CNS. Organisms also reach the CNS via colonization of ventricular drains, shunt tubing, and central venous lines.16,18,35,61,114–116 Recently, AIDS has been recognized as a predisposing factor for Candida meningitis.

Neuropathology

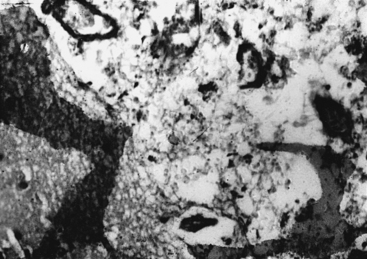

In CNS, Candida invades small blood vessels, causing thrombosis and infarction. Disseminated granulomatous lesions may be scattered throughout the meninges and brain, causing meningitis or focal encephalitis.6,9,18 Candida meningitis can occur spontaneously, as a complication of disseminated candidiasis, or as a complication of an infected wound or ventriculostomies via direct inoculation of the organism into the CNS.61 At autopsy, gross lesions may not be apparent. Microscopically, multiple microabscesses, small macroabscesses, and microgranulomas in the distribution of anterior and middle cerebral vessels are found.6,7,9,18 The abscesses are composed of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages that evolve to a granuloma after a week. On histology, they are faintly basophilic when stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) but are intensely stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and methenamine silver reaction.6,7,9,11,13,14

Clinical Presentation

The clinical symptomatology of CNS candidiasis is that of low-grade meningitis.55,62 A marked basal infiltrate may cause multiple cranial nerve palsies and deterioration in the level of consciousness, which is frequent in later stages of the disease, together with hydrocephalus.51,64 In acute meningitis, the signs of meningeal irritation are present. In newborns, particularly a low-birth-weight neonate, the diagnosis is difficult and delayed, leading to permanent neurologic sequelae. Symptoms and signs in these cases are nonspecific. Mortality is very high in untreated cases, whereas with antifungal therapy, it is reduced substantially nowadays.

Spinal candidiasis is rare. It can involve the vertebral body46,49 and/or the disc space60 by hematogenous spread in patients with Candida sepsis. It may occur by local invasion and as a postoperative complication of spinal surgery. Persistent low back pain is a common complaint; however, 50% of cases may have significant neurologic deficits. Neuroimaging studies show nonspecific spondylitis and discitis. Among 12 patients of CNS candidiasis in our series, 8 patients presented with meningitis, 1 patient presented with encephalitis–cerebritis, 2 patients presented with cerebral abscesses (treated with aspirations), and the remaining patient presented with upper cervical cord syndrome (diffuse cord changes at autopsy) associated with cervical vertebral osteomyelitis and discitis. One patient with meningitis also had a cerebral abscess, which was successfully drained by computed tomography (CT)–guided stereotactic surgery, with good outcome (Fig. 149-1).

Diagnosis

Candidiasis diagnosis should be suspected in patients with external ventricular drains or blocked shunts. CSF examination, including cultures, should be routine. The CSF may show a pleocytosis, with either neutrophils or lymphocytes predominating, and glucose is often low. Serial serum examinations (double diffusion, counterimmunoelectrophoresis, immunofluorescence, and latex agglutination tests) are helpful. Positive blood and CSF cultures provide definitive diagnosis. Funduscopic examination is invaluable, detecting endophthalmitis before permanent loss of vision occurs. Bone or disc biopsy, histology, and culture principally make the diagnosis of spinal candidiasis.5,9,18

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in fungal spinal osteomyelitis usually shows hypointensity of the vertebral bodies on T1-weighted images, with enhancement on contrast administration. There is lack of hyperintensity within the discs on T2-weighted images with preservation of the intranuclear cleft, which is in contrast with pyogenic osteomyelitis, where the intervertebral disc may be hyperintense with loss of intranuclear cleft on T2-weighted images.117 The diagnosis may be made by percutaneous needle aspiration of the involved area.

Treatment

Amphotericin-B, flucytosine, fluconazole, miconazole, and ketoconazole have been used successfully in spinal candidiasis. Decompressive surgery is usually required in patients with significant compressive spinal lesions. If there is an evidence of pus collection on spinal MRI, then preoperative image-guided aspirations to prove the fungal nature of the lesion should be followed by preoperative antifungal medications; surgical débridement and fixation should be carried out with a full postoperative course of antifungal medications to achieve good results in many cases.118 Fluconazole (with amphotericin-B in the initial phases) for 3 to 6 months postoperatively may lead to healing of fungal osteomyelitis with osseous consolidation.119 The overall prognosis is better than in earlier times due to combined medical and surgical therapies.

Histoplasmosis

Histoplasmosis is present throughout the world. It is the most frequently observed pulmonary mycotic infection in the eastern and central United States, whereas in Europe its incidence is low. It is known to invade the reticuloendothelial system.3,6,9,13,14,18 Lesions are found in the spleen, liver, and lymph nodes, as well as the lungs. CNS involvement is rare. The causative organism (2- to 5-μm yeast) is H. capsulatum, a dimorphic fungus. It is commonly found in soil. Organisms are inhaled with dust contaminated by chicken, bird, or bat excreta. The primary focus is formed in the lungs, which become calcified, but may occur in the mouth, gastrointestinal tract, or skin. In immunocompetent individuals, CNS histoplasmosis is extremely rare,99 but many patients with CNS involvement are immunocompromised by burns, antibiotics, steroids, and AIDS.6,101 Even though about 25% of the population in the United States have positive histoplasmin skin tests, CNS involvement is rare.18 Hematogenous dissemination may spread to the CNS. Neurologic involvement occurs in 10% to 20% of patients with disseminated histoplasmosis.

Neuropathology

Involvement of the CNS in histoplasmosis occurs in less than 1% of all patients with active histoplasmosis and includes diffuse leptomeningitis, discrete granuloma, periventricular granulomata, parenchymal granulomatosis, choroid plexus granulomata, and granulomatous arteritis.6,9,13,18,101,104 In diffuse basilar leptomeningitis, there is thickening of the leptomeninges, thick yellow exudate with miliary granulomas along the blood vessels. In chronic cases, meningeal fibrosis with hydrocephalus develops. Meningitis is proportionally less prominent in histoplasmosis than in cryptococcosis and coccidioidomycosis. Histoplasmosis granulomas mimic sarcoidosis, other fungal, or tubercular mass lesions consisting of central noncaseating granulomas or small caseous areas surrounded by macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and Langhans giant cells. It is well shown with PAS. In sections stained with H&E, shrinkage of the organisms produces a halo and gives an impression of a capsule.9 Methenamine silver stain demonstrates macrophages packed with organisms, reactive gliosis, and fibrosis.

Clinical Presentation

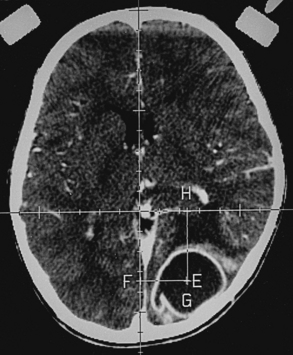

Histoplasmosis has two peaks of incidence: one in early childhood and the other in middle age.104 Four forms are described as leptomeningitis, cerebritis, military granulomas, and spinal cord lesions. Leptomeningitis is common, whereas other CNS lesions in histoplasmosis are rare. The condition usually presents as chronic meningitis with or without hydrocephalus. Mass lesions are rare (Fig. 149-2), and occasionally chorioretinitis is seen. The skull and vertebrae may be involved by osteomyelitis with secondary spinal cord compression, especially with H. duboisii.5,104

Diagnosis

The clinician should maintain a high index of suspicion with patients who are from any area endemic for histoplasmosis. Definite diagnosis is made by demonstration of organism by culture of sputum, CSF, and serum or on histology.99–104 C fixation, agar gel, diffusion testing, and radioimmunoassay (urine or serum) are helpful. Biopsy supplies a more definitive answer. The CSF is usually under pressure, shows a moderate pleocytosis up to 300 cells per cubic millimeter, and is more often mononuclear than polymorphonuclear in type. Proteins are elevated, glucose is somewhat reduced, and the organism is cultured from the CSF samples in about 50% of cases. Peripheral blood smear and bone marrow examination may yield early diagnosis. MRI shows enhancing mass lesions in the brain. On T1-weighted images, Histoplasma lesions appear as hypointense rims, and they show surrounding edema on T2-weighted images. CT scans show ring-enhancing lesions.

Blastomycosis (North American Blastomycosis)

Blastomycosis is endemic in the southeastern regions of the United States and widely reported in Africa.17,18,58 The causative agent, B. dermatitidis, is found in the soil, may have a natural reservoir in dogs, and has worldwide distribution. The fungus is a spherical cell 8 to 15 μm in diameter that multiplies by a single bud, which is attached to the parent cell by a broad base. Blastomycosis is mainly a pyogranulomatous (blastomycoma) disease; it begins as an initial subclinical pulmonary lesion and then hematogenously spreads to other organ systems. The yeasts are phagocytized by pulmonary macrophages, which may disseminate to produce secondary lesions in the skin, bone, and genitourinary system, but the CNS rarely gets involved. In agricultural workers, the primary focus is in the lungs or skin.17–1958 Hematogenous spread of infection to the CNS occurs rarely (in about 5% of patients). In endemic areas, blastomycosis is seen in about 40% of AIDS patients.6,9,18 However, it is a less common mycotic infection when involving the CNS compared to histoplasmosis and coccidioidomycosis.120–127

Neuropathology

Primary CNS blastomycosis is extremely rare, whereas secondary CNS involvement occurs in 3% to 33% of cases of disseminated blastomycosis. Typically, cerebral blastomycosis produces leptomeningitis, meningoencephalitis, brain abscesses, paradural abscesses, and adjacent granulomas. Grossly, two fifths of cases present with chronic leptomeningitis, one third with granulomas and abscesses, and one fourth with spinal epidural granulomas and abscesses. Epidural abscesses occur rarely secondary to craniovertebral osteomyelitis. Fibrosis in subarachnoid spaces can cause hydrocephalus.125,126 Abscesses may be extradural, subdural, or intraparenchymatous in location. No region in the CNS or peripheral nervous system is immune. It may be either focal or disseminated basal leptomeningitis with fibrinopurulent exudate. This can block subarachnoid spaces, causing hydrocephalus. Pachymeningitis may result. Histologic features elicit a mixed granulomatous and suppurative reaction. The center of an abscess contains caseous necrotic material with cells (lymphocytes, neutrophils, plasma cells, macrophages, and Langhans giant cells) and organisms. H&E unstained wet preparation, PAS, and methenamine silver stain demonstrate the organism. Bone and vertebral disc destruction with paraspinal abscess closely simulates tuberculous disease of the spine.5,58,121,123,127

Clinical Presentation

CNS blastomycosis presents with headaches and neck stiffness; intracranial blastomycotic abscesses or granulomas result in increased intracranial pressure (ICP) with or without localized signs.120,125,126 Eventually, these patients develop convulsions, mental deterioration, confusion, and lethargy. Plain CT scan may show iso- or hyperattenuation lesions. However, small solitary lesions show homogeneous enhancement on CT scanning with surrounding edema. Slightly bigger lesions may show ring-enhancing lesions with surrounding edema. In our series, all six patients with CNS blastomycosis presented with signs and symptoms of raised ICP, mainly due to granulomas. Motor impairment, cranial nerve palsies, and visual symptoms were also encountered in varying degrees. One patient had rhino-orbital blastomycosis, and another patient had blastomycosis of mastoid sinus. Initial clinical impression in four cases was a progressive space-occupying lesion, and in two cases, a space-occupying lesion was seen with meningeal signs. Neurosurgical interventions for the intraparenchymatous lesions as seen on CT scans resulted in good outcome in five patients with histologic diagnosis of blastomycotic granuloma. One patient died who had postmortem evidence of meningitis, subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), cerebral abscess, and cerebral infarction, in addition to a cerebral granuloma. Blastomycosis in African countries commonly affects the thoracic spine, ribs, and sternum by direct extension from the lungs.121,123,127 Osteomyelitis and discitis are associated with paraspinal abscess formation.5,123 Clinical and radiologic features are similar to tuberculosis, with which blastomycosis sometimes coexists.5

Coccidioidomycosis (Modeling Valley Fever)

Coccidioidomycosis is caused by C. immitis, which is probably the most virulent fungi, causing human mycoses accounting for about 100,000 cases per year in the United States, with 70 to 80 deaths annually.128–132

It is a geographically restricted mycosis, which includes regions of semiarid climate. Its distribution corresponds to areas where warm temperatures and dry conditions exist. It is endemic in the southwestern United States (especially in San Joaquin Valley, California, and in Arizona, where 85% of the population is skin test positive), Mexico, and South America, particularly Argentina and Paraguay.133,134 Both mycelia and spores are carried a considerable distance by wind or transported by rodents. The causative organism C. immitis is a nonbudding spherical structure measuring 20 to 70 μm in diameter with a double refractile capsule. Mature forms are filled with numerous small (two to five) endospores. C. immitis is a dimorphic fungus producing hyphae and arthroconidia (arthrospores) in its saprophytic (soil) environment and spherules (sporangia) in infected tissues. Pulmonary infection is contracted by inhalation of the airborne arthroconidia in immunocompetent or immunocompromised individuals. Most infections are self-limited. About two thirds of cases of pulmonary infections are asymptomatic, while one third of cases develop mild through severe pulmonary disorders. However, the majority of patients recover and develop strong, specific immunity against infection.135–138 The fungus is therefore considered both a pathogen and an opportunist. Hematogenous spread to the CNS occurs in about 50% of cases as a terminal event.6,18

Neuropathology

With coccidioidomycosis, meningeal inflammation results in accumulation of exudate, opacification of leptomeninges, and obliteration of sulci with caseous granulomatous nodules at the base of brain and in the cervical region.6,9,18,131,134 Extensive fibrosis causes obstructive hydrocephalus. Invasion of blood vessels leads to multiple aneurysms.131 Unusually large granulomatous lesions and frank abscesses can occur in the brain or spinal cord parenchyma. The microscopic picture mimics tuberculous meningitis. Meningeal fibrosis, granulomas (organisms surrounded by epithelioid cells, giant cells, lymphocytes, and plasma cells), small abscesses with caseous necrosis, and vascular invasion are seen. On H&E stains, Coccidioides are basophilic, and they are well demonstrated with methenamine silver stains.

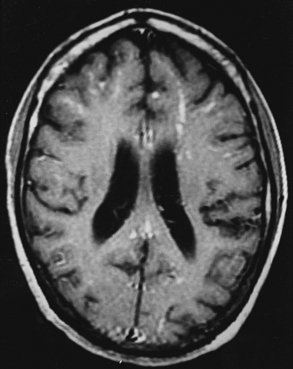

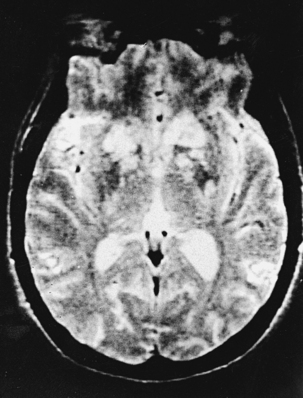

Clinical Presentation

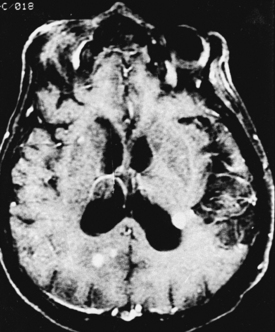

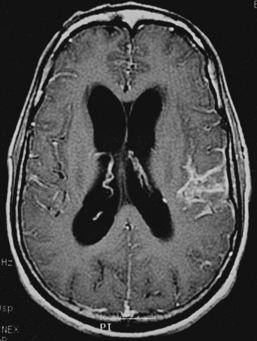

CNS coccidioidomycosis presents as acute, subacute, or chronic symptomatic meningitis; transient focal deficits (aphasia and hemiparesis); confusion; restlessness; and depression. Multiple cranial nerve palsies, raised ICP, and hydrocephalus occur as complications of basal meningitis, and/or mass lesion.128,133–138 Donor-related coccidioidomycosis in organ transplant recipients is also described. In our series, one fatal case of CNS coccidioidomycosis presented with signs of raised ICP, multiple cranial nerve palsies, and rapidly progressive sensory motor impairment in limbs. MRI studies showed evidence of leptomeningitis, intraparenchymatous brain stem granulomatous lesions, and hydrocephalus (Figs. 149-3 and 149-4). A nonfatal case with cerebral granulomas and leptomeningitis was biopsied and then treated with antifungal medications. Myelopathy may result from adhesive meningitis or from a mass lesion or an extradural abscess associated with a vertebral osteomyelitis. Spinal coccidioidomycosis may present as acute or chronic spondylitis in the thoracic and lumbar regions, especially in cases of disseminated coccidioidomycosis.5,130 Apart from vertebral bodies, the pedicles, transverse processes, laminae, spinous processes, and contiguous ribs may be affected; however, intervertebral discs are relatively spared. Coccidioidomycosis usually presents as progressive spinal cord compression.5,130,134 Paraspinal masses and sinuses are commonly seen, and meningitis rarely occurs, with fatal outcome.

Diagnosis

With coccidioidomycosis, CSF is usually under increased pressure but occasionally shows evidence of a spinal block. Raised proteins, reduced glucose, and a persistent pleocytosis may be present, and the organisms can be recognized in wet preparations of the CSF. A high index of suspicion for raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate, calcified nodes on chest x-ray, and craniospinal bone lesions on CT scans/MRI of the cerebrospinal axis (mass lesion and hydrocephalus) form the mainstays of investigations. Osteomyelitis of the skull or vertebrae may be visible on the plain x-ray film. Osteomyelitis may also present as causing punched-out lesions on skull films and an underlying abscess on CT/MRI studies. Radiolucent vertebral lesions devoid of surrounding sclerosis in early cases and dense sclerotic vertebrae with normal disc spaces in late states are features seen on plain x-ray films. However, bone changes and paraspinal lesions are well delineated on CT/MRI studies. Differential diagnosis includes multiple myeloma, sarcoidosis, histiocytosis, and metastases. It is unusual for coccidioidomycosis to present as a solitary bone lesion, which may mimic a primary bone tumor. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy helps the clinician differentiate between inflammatory and neoplastic processes involving bone by acquiring material for cytologic studies and cultures.135

Treatment

Antifungal drugs effective against coccidioidomycosis include amphotericin-B and azoles (ketoconazole, fluconazole, and itraconazole). Intravenous amphotericin-B is the most promising drug, with intrathecal administration via lumbar puncture or a subcutaneous reservoir in seriously ill or deteriorating cases. In cases of severe pulmonary compromise, where an early response is highly desired, amphotericin-B is used for its rapid onset of action. Azoles are used for the chronic processes. When localized mass lesion is causing compression of the brain/spinal cord, appropriate neurosurgical intervention is carried out and intrathecal azoles have been used. Coccidioidomycosis osteomyelitis remains a rare but difficult disease to treat, with a lifelong risk of recurrence. Spinal decompression and stabilization where indicated may be required, along with antifungal drugs (amphotericin-B/ketoconazole).5,6,17,18,130,134

Paracoccidioidomycosis (South American Blastomycosis)

Paracoccidioidomycosis is a chronic progressive granulomatous disease primarily spreading from external nares to the lungs and thereby to local lymph nodes.139–143 It is present from Mexico to Argentina and in South American countries—Brazil, Venezuela, and Colombia.6,9,18 It is especially endemic in South America and Mexico and is caused by P. brasiliensis, a dimorphic fungus. Multiple thick, walled buds arise from single yeast. The organism lives in the soil or vegetation, and farmers are most affected. Lesions of the mucous membranes, especially of the mouth, nasal passages, pharynx, and lungs, are the primary foci in previously healthy patients. Disseminated disease involves many organs, including liver, spleen, and bones. The anatomicoclinical manifestations of the disease have been classified as follows: tegumentary forms (mucocutaneous), lymphoid forms, visceral forms, and mixed forms.

Neuropathology

Three main types of pathologic CNS lesions are seen: (1) granulomas—South American blastomycomas/paracoccidioidomycomas (commonest)—(2) meningitis with or without hydrocephalus (uncommon), and (3) an abscess (rare).3,6,12–14,18,140–143 The pseudotumors or granulomas may be intraparenchymatous (common) or meningeal (uncommon). They may occur in the dura mater with clinical characteristics of meningiomas.140,141,143 Leptomeningitis is typically of the basal granulomatous type. Spread to the brain parenchyma occurs through the Virchow-Robin spaces, especially at the level of the hypothalamus and the lateral cerebral fissures. Granulomas are formed by epithelioid cells: Langhans giant cells and lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate. Nodules may resemble tubercles.

Treatment

Surgical excision of the mass lesions, together with therapy with amphotericin-B (the drug of choice), offers the best chance of paracoccidioidomycosis treatment. Sulfonamides, sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim, and ketoconazole are also helpful. Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole is one of the best combinations, with good outcome. Therapy may also consist of long-term administration of itraconazole. Early diagnosis and adequate therapy may prevent extensive tissue destructions. Long-term follow-up is mandatory. Clinical improvement may be accompanied by diminishing P. brasiliensis antigen and antibody titers in cases of neuroparacoccidioidomycosis.139–147

Sporotrichosis

Sporotrichosis is caused by S. schenckii, which is found in the soil and on the plants.4,6,9,18 Domestic cats may be an important carrier of agents of sporotrichosis to humans.148–150 The infection usually starts when the fungus is inoculated peripherally at the site of cutaneous injury or is inhaled. Lymphangitis or granulomatous pneumonitis is produced. The fungus may then disseminate hematogenously to other organs, including the CNS.

Neuropathology

Cerebral sporotrichosis shows features of chronic meningitis, microabscesses, and granulomas.6,18 Microscopically, widespread cortical granulomatous microabscesses in the brain, spinal cord, or spinal nerve rootlets are seen.

Cryptococcosis (European Blastomycosis)

Cryptococcosis is one of the commonest CNS fungal infections in immunocompromised patients.151,152 It is ubiquitous but more common in Europe than elsewhere.18 It is a generalized systemic visceral mycosis affecting previously healthy people66; however, in 50% of cases, it has been reported in immunocompromised subjects, children, and middle-aged and older males.24 Pigeon breeders are at special risk. The causative agent, C. neoformans, is a spherical budding capsulated yeast (5-20 μm) (Fig. 149-5). It is found in soil and wood contaminated with bird excreta. It has been isolated from fruit juices and milk. C. neoformans neoformans causes disease in immunocompromised hosts, and C. neoformans gattii is the cause in immunocompetent hosts6; the portal of entry is the respiratory system. The primary focus lies in the lungs, from which secondary systemic dissemination occurs via hematogenous spread. There is a strong neurotropic tendency to involve meninges and the brain.105–113143 CNS cryptococcal infection commonly presents with meningitis (subacute or chronic) or meningoencephalitis. Acute fatal meningitis occurs rarely in cryptococcosis. Usually, chronic meningitis present with the periods of remission and relapses. Cryptococcosis is one of the common CNS fungal infections in immunocompromised patients: nearly one tenth of patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) develop cryptococcosis, and many HIV patients have cryptococcal meningitis as their initial clinical presentation.

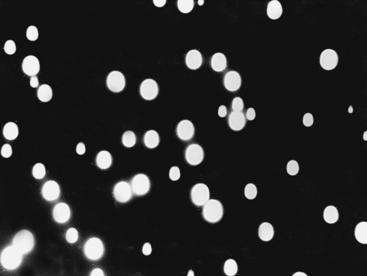

FIGURE 149-5 India ink preparation of the CSF showing the mucoid capsule of the cryptococcal spherules.

Neuropathology

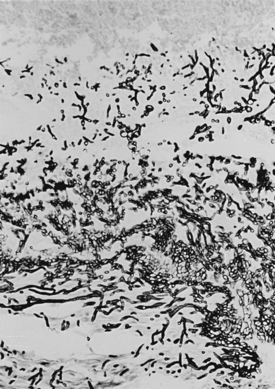

With cryptococcosis, the leptomeninges become infiltrated, thickened, and opaque (Fig. 149-6).3,8,17,18,143 The Virchow-Robin spaces around penetrating vessels are distended with organisms (Fig. 149-7).6,18 Granulomatous lesions can be found in the cerebral or spinal parenchyma. Spinal arachnoiditis may also be present. Chronic fibrosing leptomeningitis may cause hydrocephalus. Less commonly, intraparenchymatous cysts are seen (basal ganglionic regions), related to exuberant mucinous capsular material produced by the proliferating cryptococci.7,105,109,131 Rarely, fungi aggregate in an inflammatory lesion and produce small or large granulomas (cryptococcomas or torulomas) in the meninges, parenchyma, ependymal surfaces, or choroid plexuses.

Microscopic examination shows three types of tissue reactions: (1) disseminated leptomeningitis, (2) granulomas, and (3) intraparenchymal cysts.3,6,18,107,143 In meningitis, there is minimal inflammatory response. The capsule of the fungus seems to impede inflammation by masking surface antigen. Inflammatory response consists of lymphocytes (mainly), plasma cells, eosinophils, fibroblasts, and multinucleated giant cells (studded with cryptococci).6,9,143 Glial reaction and associated cerebral edema are minimal. Granulomas are rarer late tissue reactions mimicking tubercles. They are composed of fibroblasts, giant cells (with fungal organisms), and necrotic areas. Multiple intraparenchymal cysts related to exuberant capsular material produced by the proliferating cryptococci create honeycomb-like cystic cerebral changes, especially in the basal ganglia. No membrane or capsule surrounds these cysts, which are well delineated from the surrounding tissue.9,143,151,152 Inflammatory response (macrophages with fungi and giant cells) around these cystic lesions is minimal. In our series of 22 cases, 21 cases presented with meningitis, and in an autopsy study in 17 cases, meningitis was confirmed in the form of thickened, hazy meninges with a characteristic slimy exudate over the superolateral surfaces and base of the brain. Among the secondary features, only 3 cases showed multiple granulomas in the cerebral hemispheres, hypothalamus, and, in 2 of these 3 cases, in the brain stem. Tiny cryptococcal cysts in the brain parenchyma containing plasma-like coagulated material were seen in 13 cases, and multiple areas of cystic degeneration destroying the brain parenchyma extensively and containing cryptococci were found in 13 cases (Fig. 149-8). In 1 case, multiple areas of demyelination with coexisting cerebral edema were seen, and in 4 cases, dilated ventricles were noted. In 2 biopsy cases, the structure of a granuloma consisted of inflammatory granulation tissue with foreign body giant cells and cryptococci. In 1 case of cerebral astrocytoma grade II, cryptococcosis was present within the tumor tissue and was well managed following surgery.

Clinical Presentation

CNS cryptococcosis commonly presents with nonspecific manifestations. At onset, patients usually present with headaches, nausea, vomiting, visual impairment, and papilledema; at a later stage, neck stiffness develops, followed by fever, personality changes, seizures, deterioration in sensorium, cranial nerve palsies, and hydrocephalus.7,108 In many patients, there are no physical signs. Periods of remission and relapses are noted. Cryptococcomas may produce prolonged, unresolving, focal neurologic deficits. Acute fatal meningitis in cryptococcosis is extremely rare.6,7 In our series, all 21 cases of CNS cryptococcosis presented with signs and symptoms of meningitis with raised ICP. Fever, headache, and vomiting were the commonest presenting symptoms. Altered sensorium, cranial nerve palsies, and visual symptoms were seen in 6 cases, and fatal meningitis occurred in 2 cases. Spinal cryptococcal arachnoiditis may present with progressive myelopathy or myeloradiculopathy.105–113143

Diagnosis

The fungal capsule is transparent with cryptococcosis; therefore, the CSF appears clear, although it is mildly xanthochromic and under high pressure. The cell count may go up to 100 cells per cubic millimeter (mainly lymphocytes and polymorphs). The sugar and chloride levels are reduced, and total proteins may be raised. As the fungal capsule is transparent on routine microscopy, India ink preparation of the CSF can demonstrate a mucoid capsule. Organisms can be seen in tissues with PAS and methenamine silver stains.6,9,18 On mucicarmine and alcian blue stains, the fungal capsule is well recognized. However, routinely, CNS cryptococcosis is diagnosed by positive cryptococcal antigen titer and India ink staining of the CSF film preparation. Chest x-ray (pulmonary lesion) and CT/MRI brain scans (brain edema, hydrocephalus, basal meningitis, granuloma, and intraparenchymal cysts) are helpful (Figs. 149-9 and 149-10). The commonest patterns of CNS cryptococcosis are ventricular dilation in CT scans and Virchow-Robin space dilation in MRI. MRI is more sensitive in detecting CNS cryptococcal infection, such as Virchow-Robin space dilation and leptomeningeal enhancement. There is no significant pattern difference between immunocompromised and nonimmunocompromised patients with CNS cryptococcosis.142 The CSF culture should be done at 30°C for 5 days. This organism can be isolated in 95% of cryptococcal meningitis cases. Positive latex agglutination testing with rising serum titers of polysaccharide capsular antigen is of prognostic value.

Treatment

Untreated cryptococcal meningitis is generally fatal. Early aggressive therapy with combined amphotericin-B and flucytosine offers best chances of cure. Alternatively a 6-week course of amphotericin-B followed by maintenance oral fluconazole gives good results. Granulomas, cysts, and hydrocephalus are treated on their own merits. Predisposing factors should be carefully corrected. Failure of treatment raises the possibility of an underlying medical disorder, such as AIDS. Patients receiving treatment before CNS complications have a good prognosis.

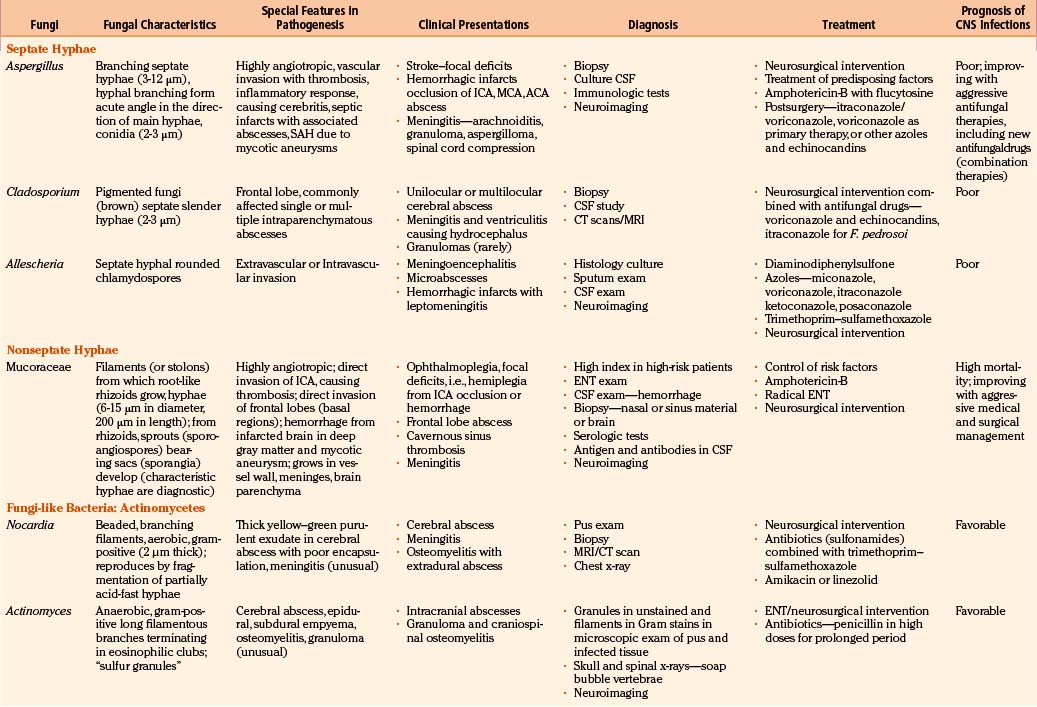

Septate Hyphae Causing Infections of the Nervous System

Aspergillosis

However, routinely, the majority of cases of aspergillosis are reported from countries with a temperate climate, where constant exposure to the high spore content of pathogenic Aspergillus species is present in the moldy work environment. Several species of Aspergillus can cause CNS infection, but most cases are due to A. fumigatus (primary pulmonary infection), A. Niger (primary otitic infections), A. flavus (primary paranasal sinus infection), and A. terreus.15,83 These are saprophytic, opportunistic, ubiquitous fungi found in soil, plants, and decaying matter and consisting of branching septate hyphae varying from 4 to 12 μm in width (Fig. 149-11). Aspergillus species have a worldwide distribution. The primary portal of entry for Aspergillus is the respiratory tract. Infection either reaches the brain directly from the paranasal sinuses via vascular channels or is bloodborne from the lungs and gastrointestinal tract.66–87 The infection may also be airborne, contaminating the operative field during a neurosurgical procedure.15

Neuropathology

In the majority of cases, CNS aspergillosis occurs due to sinocranial origin, where skull base syndromes are the presenting features. The primary focus lies commonly in the paranasal sinuses. Chronic mycoses of the paranasal sinuses result in orbital, cranial, and intracranial (extradural, dural, and intradural) fungal lesions.153–157 Aspergillus has a marked tendency to invade arteries and veins (angiotropic), producing a necrotizing angiitis, secondary thrombosis, and hemorrhage.3,6,9,18,83 Onset of cerebral aspergillosis may be heralded by acute manifestations of focal neurologic deficits in middle cerebral artery (MCA) and anterior cerebral artery (ACA) distributions.3,6,9,66–87 In our series of 72 cases, 28 cases had granulomas causing neurologic deficits, 6 cases had intracranial abscesses (five intraparenchymatous and one interhemispheric), 9 cases had primary presentation as internal carotid artery (ICA) thrombosis with rhinosinoaspergillosis, and in 7 other cases, ICA/basilar artery thrombosis was an associated feature. However, 15 patients presented with an acute stroke due to hemorrhagic infarction, and in 6 other patients, infarction developed during the course of management. The evolving hemorrhagic infarcts may convert into septic infarcts with associated cerebritis and abscesses. The fungal hyphae are found in large, intermediate-sized, and small blood vessels with invasion through vascular walls into the adjacent tissue; invasion in the reverse direction can also occur.9 Purulent lesions may be chronic and have a tendency to fibrosis and granuloma formation (Figs. 149-12 and 149-13). Microscopically, the most striking feature is the intensity of the vascular invasion with thrombosis, as was seen in our 20 cases as vasculitis; in 14 cases as ICA, MCA, and ACA thrombosis; and in 2 cases as coexisting basilar thrombosis. In purulent lesions (7 cases in our series), the pus is seen in the center of the abscesses with abundant polymorphs at the periphery. Granulomas consist of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and fungal hyphae as seen in 28 cases in the present study.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree