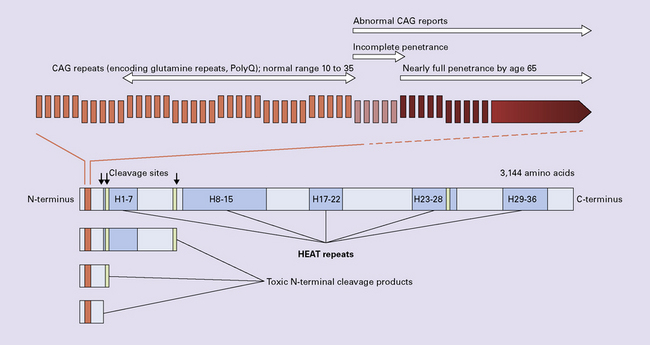

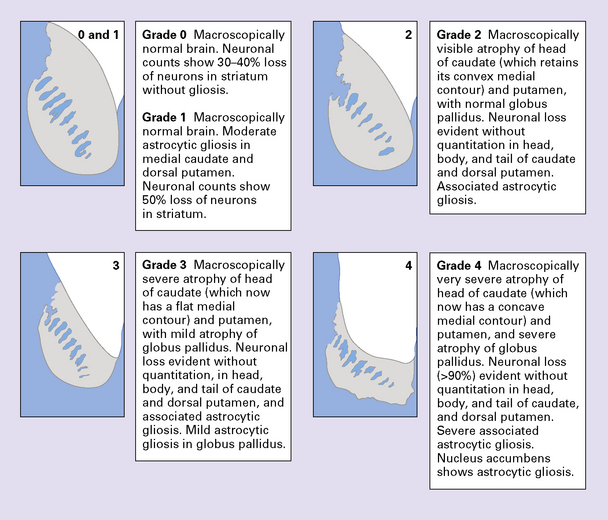

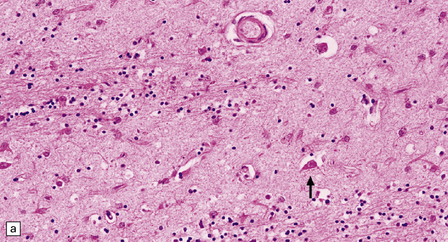

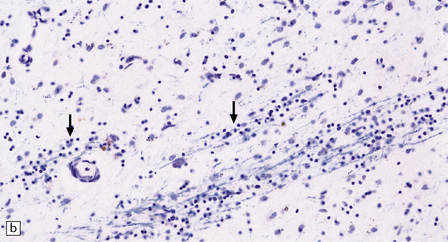

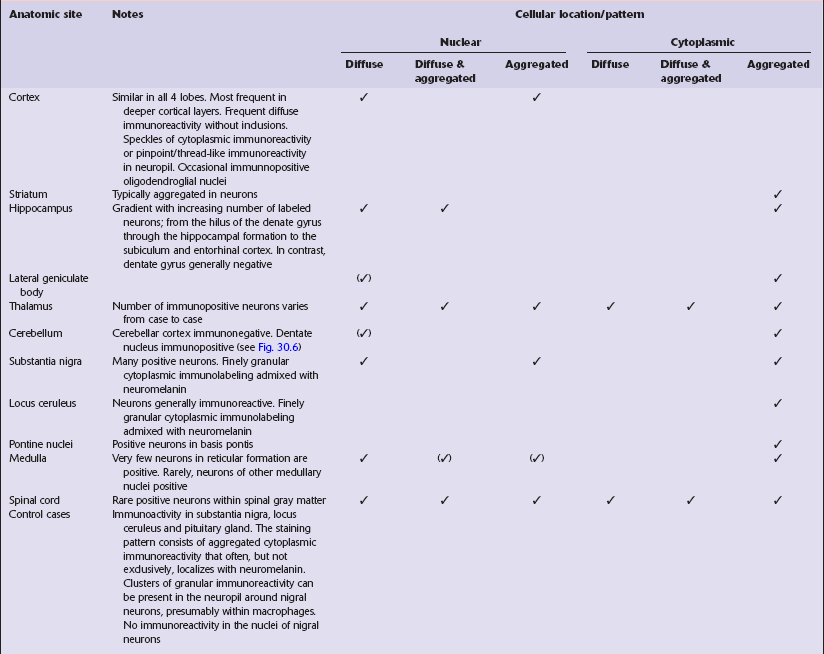

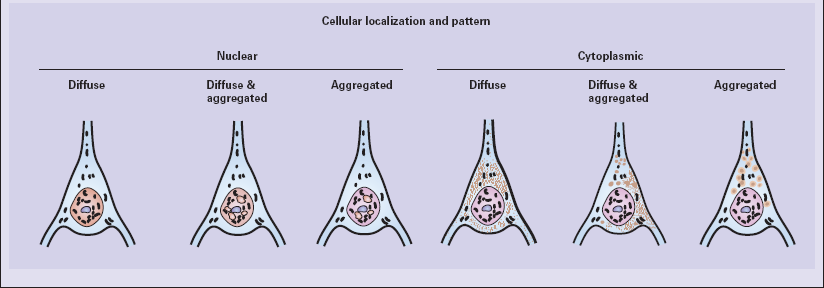

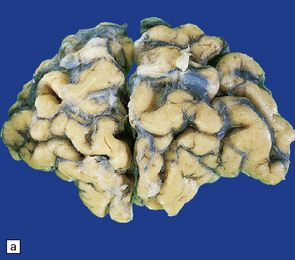

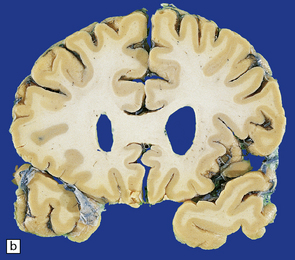

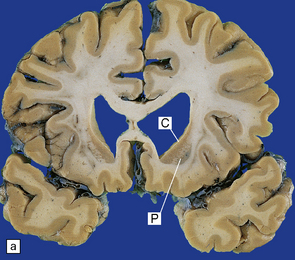

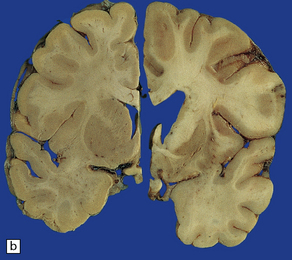

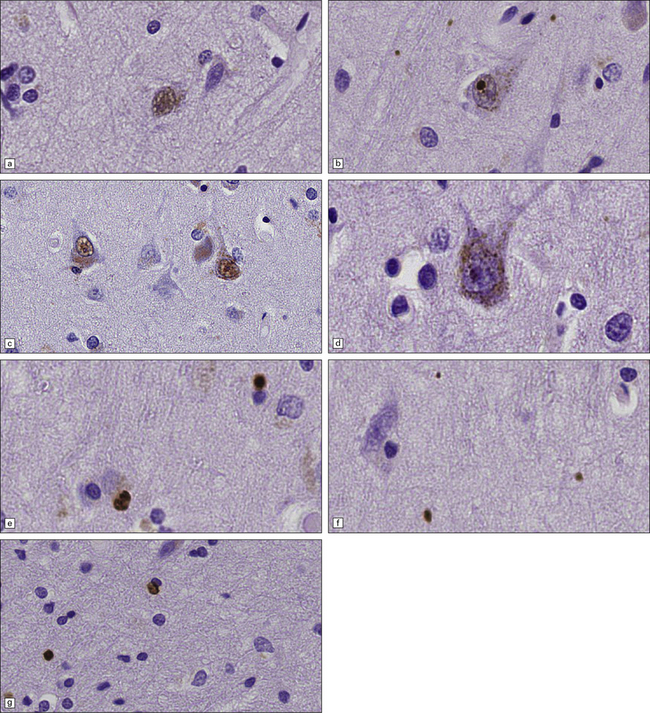

30 The Vonsattel grading scheme for the severity of atrophy of the basal ganglia correlates with the clinical severity of disease (Fig. 30.2). Cerebral atrophy is usually present (Fig. 30.3) with a reduction in brain weight of approximately 30%. This is associated with a 21–29% loss of volume of the cerebral cortex and a 29–34% loss of white matter. The most characteristic macroscopic abnormality is atrophy of the caudate nucleus, putamen, and globus pallidus (Fig. 30.4). 30.3 Cerebral atrophy in HD. 30.4 Striatal atrophy in HD. The most marked histologic changes are seen in the basal ganglia where loss of neurons is associated with astrocytic gliosis in affected areas of the striatum (Fig. 30.5). In general, morphometric studies are required to show loss of large pyramidal neurons in the neocortex and hippocampus, which occurs in the absence of astrocytosis. Neuronal loss may also be found in the hypothalamus, substantia nigra, and cerebellar cortex, particularly in severe early-onset cases. The neuronal loss from the striatum preferentially affects certain neuronal subtypes. The normal striatum has two neuronal compartments: Immunohistochemical staining for ubiquitin or huntingtin reveals pathological accumulation of huntingtin protein within intranuclear inclusion bodies or in neurites. Abnormal neurites have been shown to be widely distributed throughout the cortex in HD by immunostaining for ubiquitin. Intranuclear inclusions are found in cortical neurons (Fig. 30.6 and Table 30.1). However, inclusions tend to be numerous only in cases with a long expansion repeat and hence a younger age of onset. In late-onset cases associated with a short expansion nuclear inclusions may be sparse. 30.6 Patterns of huntingtin accumulation, revealed by labeling of polyglutamine repeats with the antibody 1 C2. The labeling may be diffuse, or aggregated into granules or discrete inclusions. Combinations of nuclear and cytoplasmic inclusions are occasionally seen.

Hyperkinetic movement disorders

CHOREA

HUNTINGTON DISEASE (HD)

Juvenile onset (4–19 years of age) accounts for 10% of cases and is particularly linked to paternal transmission.

Juvenile onset (4–19 years of age) accounts for 10% of cases and is particularly linked to paternal transmission.

Early onset (20–34 years of age).

Early onset (20–34 years of age).

Mid-life onset (35–49 years of age).

Mid-life onset (35–49 years of age).

Late onset (over 49 years of age) accounts for 25% of cases and is particularly linked to maternal transmission.

Late onset (over 49 years of age) accounts for 25% of cases and is particularly linked to maternal transmission.

PATHOLOGIC GRADING OF SEVERITY

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

(a) Surface of frontal lobe showing mild gyral atrophy. (b) Coronal section showing mild gyral atrophy.

(a) Characteristic atrophy of the caudate nucleus (C) and putamen (P) in HD. There is also generalized widening of the cerebral sulci. (b) Comparison of a normal cerebral hemisphere (left) with that from a patient with HD (right), illustrating the severe atrophy of the basal ganglia.

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

The patch (striosome) compartment. Most patch neurons have spiny dendrites, as revealed by Golgi impregnation (spiny neurons), and contain the neurotransmitters gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), enkephalin, dynorphin, and substance P.

The patch (striosome) compartment. Most patch neurons have spiny dendrites, as revealed by Golgi impregnation (spiny neurons), and contain the neurotransmitters gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), enkephalin, dynorphin, and substance P.

The matrix compartment. Most matrix neurons have smooth dendrites (aspiny neurons), and contain acetylcholinesterase (large aspiny neurons), or the reduced form of nicotinamide–adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) diaphorase (NO synthase), somatostatin, neuropeptide Y, and cholecystokinin (small aspiny neurons).

The matrix compartment. Most matrix neurons have smooth dendrites (aspiny neurons), and contain acetylcholinesterase (large aspiny neurons), or the reduced form of nicotinamide–adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) diaphorase (NO synthase), somatostatin, neuropeptide Y, and cholecystokinin (small aspiny neurons).

The types of inclusions vary between different brain regions (see Table 30.1). (a) Diffuse nuclear, (b) aggregated nuclear (the aggregate is not in the nucleolus), (c) diffuse nuclear and cytoplasmic, and (d) granular, cytoplasmic-only inclusions. (e) Cytoplasmic inclusions in the cortex, (f) small aggregates in the neuropil, and (g) aggregates in oligodendrocytes of the subcortical white matter.