Intervertebral Disk Disease and Radiculopathy

Peter D. Angevine

Hani R. Malone

Paul C. McCormick

INTRODUCTION

Intervertebral disk disease is responsible for a range of pain syndromes that have been recognized since the time of Hippocrates. The first reported treatment of intervertebral disk pathology occurred in 1909, when Krause operated on a patient who had been diagnosed by Oppenheimer as suffering from a lesion localized to the L4 root. In surgery, Krause found an extradural mass that was described pathologically as a chondroma and the operation to remove it apparently affected a cure. In 1934, Mixter and Barr were the first to point out that these lesions were actually fragments of intervertebral disks and that they were responsible for radicular pain. They further proved the efficacy of surgical treatment in their series of 58 patients treated with laminectomy and diskectomy for lumbar disk herniation.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Symptoms related to intervertebral disk disease, particularly low back pain, are common. Pathologic studies have demonstrated that almost all individuals older than the age of 30 years have some evidence of disk degeneration. As individuals age, spondylosis and osteochondrosis, the long-term sequelae of degenerative disk disease, become more and more prominent. Intervertebral disk rupture is most common in the fourth to sixth decades of life. It is relatively rare before age 25 years and less common after age 60 years. Importantly, pathologic or radiographic findings consistent with disk disease are often asymptomatic and clinically insignificant. Although some maintain that degenerative disk disease is a byproduct of the modern human environment, there is no conclusive evidence that back pain has significantly increased over the past 50 years. Fortunately, the efficacy and morbidity associated with treating intervertebral disk disease has improved considerably.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

INTERVERTEBRAL DISK DISEASE

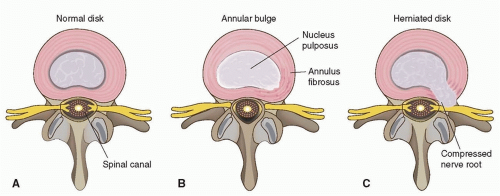

Displaced disk material may cause signs and symptoms by bulging or protruding beneath an attenuated annulus fibrosus, or the material may extrude through a tear in the annulus and project directly into the spinal canal (Fig. 109.1). In either case, the encroaching disk material may irritate or compress nerve roots as they approach their exit through the neural foramina. In cervical and thoracic regions, the problem is more neurologically complex because the spinal cord itself, as well as the adjacent nerve roots, may be involved. At cervical and thoracic levels, signs and symptoms are caused either by cord compression or a combination of cord and nerve root compression. In the lumbar region, signs and symptoms solely relate to the compression of nerve roots or to compression of the cauda equina if the disk is large enough to crowd the entire spinal canal.

There are eight spinal nerve roots in the cervical spine (C1-C8), which are numbered according to the caudal vertebra of the corresponding disk space. For example, the C4 nerve root exits through the neural foramen at the C3-C4 level and the C5 nerve root exits via the C4-C5 foramen. The C8 nerve root courses through the C7-T1 intervertebral foramen, as there is no C8 vertebra. Conversely, nerve roots in the thoracic and lumbar spine are numbered according to the vertebrae rostral to their exit through the intervertebral foramen. For example, the L5 nerve root exits the spinal canal at the level of L5-S1.

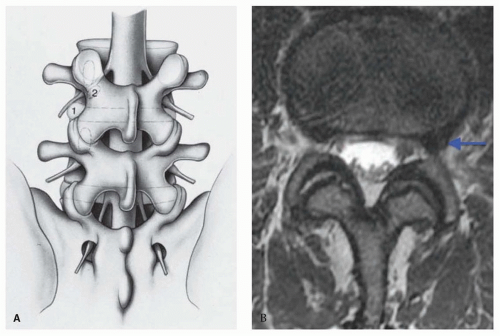

Importantly, paramedian lumbar disk herniations generally impinge on nerve roots that exit the spinal canal, a level below the site of disk herniation. For example, a paramedian herniated disk at the L4-L5 level compresses the L5 nerve root, which exits the spinal canal through the L5-S1 intervertebral foramen. This is not the case for far lateral disk herniations, which extend laterally to compress the rostral lumbar nerve root at the affected level. A far lateral L3-L4 lumbar disk herniation, for example, may compress the L3 nerve root either within the foramen or more distally as the root passes over the disk space (Fig. 109.2). Far lateral disk herniations account for 10% of all lumbar disk herniations, affect higher lumbar levels, and are likely to cause objective neurologic deficit. A far lateral disk herniation should be suspected with acute onset of an isolated upper lumbar radiculopathy that affects L2, L3, or L4.

In the cervical spine, degenerative disk disease most commonly affects the C5-C6 and C6-C7 levels. In the lumbar spine, most disk degeneration occurs at the L4-L5 and L5-S1 levels. This pattern suggests that the dynamics of pathologic change are partly related to wear and tear and to the trauma of motion.

Thoracic disk protrusions, except at the lower thoracic levels, differ from cervical and lumbar disorders in both genesis and histopathology. Motion does not play a significant role, as thoracic vertebrae are designed for stability rather than motion, and the heavy rib cage contributes to the rigidity of this region. Ruptured thoracic disks are markedly different on gross and microscopic examination and their consistency seldom resembles that of cervical and lumbar ruptured disks. These pathologic differences suggest a separate mechanism of injury in thoracic disk disease. Trauma has been accepted as a prime cause of thoracic disk herniation, but genetic predisposition also likely plays a role. Trauma may aggravate this susceptibility and ultimately catalyze rupture. Intervertebral disk disease is far less common in the thoracic spine compared to lumbar and cervical segments.

The signs and symptoms of herniated disks relate not only to the size and strategic location of the disk fragments but also to the size and configuration of the spinal canal. Congenital spinal stenosis, which is an abnormally narrow spinal canal, is an example of an inherited anomaly that influences the clinical impact of disk disease. Degenerative spondylosis leads to spinal stenosis and narrowing of the neural foramina through osteophyte formation and hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum and facet joints. Degenerative spondylosis and congenital spinal stenosis are major contributors to compression syndromes of the spinal cord and cauda equina, as even small disk protrusions in these patients can further compromise an already limited canal. In a canal of normal dimensions, the severity of neural compression and the clinical impact of a protruded disk fragment depends more on the site of rupture and the volume of the extruded material.

CLINICAL FEATURES

CHRONIC LOW BACK PAIN

In the United States, back pain is the most common reason for limiting physical activity in people younger than 45 years; it is the second most frequent cause of visits to a physician, the fifth cause of hospital admissions, and the third leading cause of surgery. In many countries, it is the most common cause of absenteeism from work, accounting for more than 12% of sick days. The aggregate economic cost in the Netherlands in 1991 was estimated to be 1.7% of gross national product. This figure likely represents the typical cost incurred by developed nations. In the United States, the aggregate cost of lower back pain is estimated to exceed $100 billion per year.

According to Andersson, “Chronic low back pain has become a diagnosis of convenience for many people who are actually disabled for socioeconomic, work-related, or psychological reasons.” The complexity of the problem is measured in a lengthy literature and a long list of approaches to therapy. Medications and other therapies include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opiates, and antidepressants; extradural injection of steroids; decompressive surgery; physical therapy, including massage and exercise; chiropractic treatment; and acupuncture. In Finland, a third of the direct costs were spent on complementary therapies. Multidisciplinary spine centers and pain centers may be sources of the most effective approach to management.

RADICULAR PAIN AND LUMBAR DISK DISEASE

Root syndromes of intervertebral disk disease are often episodic, so remissions are characteristic. The pain may be restricted to the back or follow a radicular distribution in one or both legs. Lumbar pain may increase after heavy lifting or twisting of the spine. No matter how severe the pain is when the patient is erect, characteristically, it is relieved when the patient lies down. Some patients, however, are more comfortable sitting and many find no comfortable position.

Physical examination often reveals loss of lumbar lordosis or flattening of the lumbar spine with splinting and asymmetric prominence of the long erector muscles. Range of motion of the lumbar spine is reduced by the protective splinting of paraspinal muscles, and attempted movement in some planes induces severe back pain. There may be tenderness of the adjacent vertebrae. When the patient is erect, one gluteal fold may hang down and show added skin creases because the gluteus is wasted—evidence of involvement of the S1 root. Passive straight leg raise is reduced in range and increases back and leg pain. Muscle atrophy and weakness or sciatic tenderness and discomfort may occur on direct pressure at some point along the nerve from the sciatic notch to the calf. This is particularly true in older patients.

The typical syndromes of root compression at lumbar levels are described in Table 109.1. Importantly, clinical signs may not be as distinct in actual practice as the table implies. More than 80% of syndromes affect the L5 or S1 nerve roots (Table 109.2). Compression of the nerve root at these levels results in “sciatica,” a sharp and burning pain that radiates down the posterior/lateral aspect of the leg to the foot or ankle (Fig. 109.3). When the lesion affects L4 or higher roots, straight leg raise does not stretch the roots above L5. The affected roots may be tensed, however, by extension of the limb with the knee flexed when the patient is prone, thus reproducing the typical radicular spread of pain. Nerve root compression is often associated with numbness and tingling. Radicular pain resulting from disk disease classically intensifies with Valsalva (coughing, defecating, sneezing).

TABLE 109.1 Common Root Syndromes of Intervertebral Disk Disease | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

THORACIC DISK RUPTURE

The thoracic spine is designed for rigidity rather than excursion, thus wear and tear from motion and stress may not cause thoracic disk protrusion, and clinical disorders are rare. Thoracic disk disease may result from chronic vertebral changes incident to Scheuermann disease or juvenile osteochondritis with later trauma. The radiographic changes of Scheuermann disease, when seen with thoracic cord compression, should raise the possibility of disk protrusion (Fig. 109.4). The small capacity of the thoracic spinal canal makes this region vulnerable to cord compression from disk herniation. By the same token, decompressive operations are more precarious and require meticulous care to avoid damaging the spinal cord. Calcific changes are common in pathologic thoracic intervertebral disks, which pose additional challenges when performing diskectomy. The lower thoracic levels, however, are more capacious, and although the conus medullaris or cauda equina may be damaged by disk protrusions, surgical approaches are less hazardous compared to higher levels.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree