Intracranial Hypotension

Emitseilu K. Iluonakhamhe

Tiffany R. Chang

Kiwon Lee

INTRODUCTION

In 1825, Magendie described a patient with symptoms of unsteadiness and vertigo resulting from hypotension of spinal fluid and ventricular collapse. A century later in 1938, Georg Schaltenbrand described a condition, which he termed spontaneous or essential aliquorrhea, that was marked by postural headache and low cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure. Intracranial hypotension occurs when there is loss of CSF volume. The loss of CSF can occur at different location of the neural axis depending on the underlying etiology. For example, CSF leaks can occur at a skull base fracture from trauma and post-dural puncture CSF leaks can occur at the spinal level of needle insertion. A similar syndrome of intracranial hypotension can be seen in patients with excessive CSF drainage by ventriculoperitoneal shunts and post craniotomy (i.e., brain sagging). An increasingly recognized etiology of intracranial hypotension is spontaneous intracranial hypotension (SIH).

SPONTANEOUS INTRACRANIAL HYPOTENSION

SIH is the result of an idiopathic CSF leak. Most spontaneous CSF leaks occur at the cervicothoracic junction or thoracic spine. Some of the proposed mechanisms include spontaneous rupture of an arachnoid membrane and a variety of dura abnormalities such as meningeal diverticula, perineural (Tarlov) cyst, localized absence of dura, as well as spontaneous dura tears occurring where the spinal roots leave the subarachnoid space. Some spontaneous leaks have been attributed to underlying connective tissue disorders such as Marfan syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (type II). Other predisposing etiologies include autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, Lehman syndrome, and neurofibromatosis type 1.

The true incidence of SIH is unknown, but the estimated annual incidence is 5 per 100,000 and a prevalence of 1 case per 50,000. It occurs more in women than men in a 2:1 ratio. Symptoms typically begin in the fourth to fifth decade of life; however, it has been reported in all age groups.

TABLE 108.1 Diagnostic Criteria for Spontaneous Intracranial Hypotension as Defined in International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd Edition | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

CLINICAL FEATURES

The most common initial presentation is a new onset of headache, typically orthostatic in nature. Additional symptoms include visual changes, diplopia, hearing changes, neck pain and/or stiffness, convulsions, nausea, and vomiting. Atypical presentations include parkinsonism, dementia, hypopituitarism, seizures, and coma. Symptoms are typically reversible with normalization of CSF pressure. Spinal symptoms including radicular symptoms and quadriparesis are rare. The onset and exacerbation of symptoms can be associated with coughing, laughing, Valsalva maneuver, and post coitus.

The diagnostic criteria for SIH as defined in International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3), is noted in Table 108.1. A diagnosis of SIH cannot be made if patient had a dural puncture within a month of onset of headache. The headache quality resembles post-dural puncture headache, but the postural component may not be as dramatic. The onset of headache in SIH is minutes to hours compared to seconds as in postdural headaches. The location is often holocephalic but may be localized to the frontal or occipital region. It is usually described as a throbbing or pressure-like headache but can also be dull in quality. The headache is alleviated by lying flat for about 15 to 30 minutes, but resolution can be delayed or incomplete. The headache is thought to be the result of loss of CSF buoyancy resulting in downward displacement of the brain, causing traction on pain-sensitive structures such as the dura or compensatory engorgement of pain-sensitive intracranial venous structures. If unmanaged, SIH can lead to a chronic daily headache that may not be orthostatic or relieved by recumbency. It is important to elicit the orthostatic nature of the headache at the initial onset, as this feature may become less obvious to the patient as the headache becomes chronic.

Important complications of spontaneous CSF leaks include subdural hematoma, bibrachial amyotrophy, cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT), and, rarely, superficial siderosis.

DIAGNOSIS

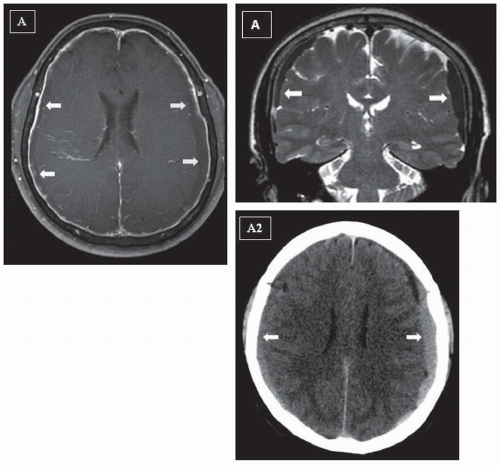

In addition to history and physical examination, use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, particularly T1-weighted

images post gadolinium injection, is useful in making the diagnosis (Fig. 108.1). Five characteristic features seen on post-gadoliniumenhanced MRI of the brain are subdural fluid collections, diffuse enhancement of pachymeninges, engorgement of venous structures, pituitary hyperemia, and sagging of the brain, which make up the mnemonic SEEPS (Table 108.2). Most observed MRI of the brain findings are a result of a compensatory change due to the loss of CSF volume. Based on the Monroe-Kellie principle, a decrease in CSF volume will result in brain sag and compensatory venous engorgement. There are several case reports that demonstrate improvement in MRI findings after successful treatment of CSF leak. It is important to note that in about 20% of patients diagnosed with SIH, the MRI findings will be normal; therefore, a normal MRI does not exclude the diagnosis of SIH.

images post gadolinium injection, is useful in making the diagnosis (Fig. 108.1). Five characteristic features seen on post-gadoliniumenhanced MRI of the brain are subdural fluid collections, diffuse enhancement of pachymeninges, engorgement of venous structures, pituitary hyperemia, and sagging of the brain, which make up the mnemonic SEEPS (Table 108.2). Most observed MRI of the brain findings are a result of a compensatory change due to the loss of CSF volume. Based on the Monroe-Kellie principle, a decrease in CSF volume will result in brain sag and compensatory venous engorgement. There are several case reports that demonstrate improvement in MRI findings after successful treatment of CSF leak. It is important to note that in about 20% of patients diagnosed with SIH, the MRI findings will be normal; therefore, a normal MRI does not exclude the diagnosis of SIH.

Opening CSF pressure can be obtained by performing lumbar puncture (LP). It is typically employed if there is a high suspicion of SIH although MRI findings are normal. LP should be performed after MRI of the brain is obtained to avoid post-LP MRI pachymeningeal enhancement, which can confound the diagnosis. A CSF opening pressure of less than 6 cm H2O is a diagnostic criterion for SIH but not a requirement. In approximately 25% of patients with SIH, the CSF opening pressure is normal. In addition to low CSF opening pressure, lymphocytic pleocytosis as well as elevated protein concentration and xanthochromia have been reported.

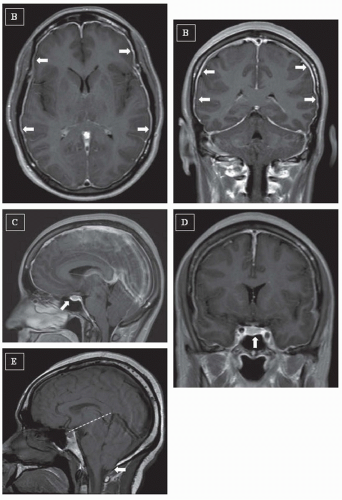

FIGURE 108.1 (continued) B: Axial (left) and coronal (right) postcontrast T1 MRI of the brain showing enhancement of pachymeninges (arrows). C: Sagittal view of postcontrast T1 MRI of the brain showing engorgement of venous structures as well as pituitary hyperemia (arrow). D: Coronal view of postcontrast T1 MRI of the brain showing pituitary hyperemia (arrow). E: Sagittal view of T1 MRI of the brain showing sagging of the brain, descent of cerebellar tonsils (arrow), and descent of the iter below incisural line (dashed line).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|