Fig. 5.1

Pelvic incidence (PI) is described as an angle subtended by a line which is drawn from the center of the femoral heads to the midpoint of the sacral endplate and a line perpendicular to the center of the sacral endplate. The sacral slope is the angle between the superior sacral endplate and a horizontal reference line, and the pelvic tilt is the angle between the line connecting the midpoint of the superior sacral plate to the center axis of the femoral heads and a vertical reference line. PI is the sum of the sacral slope (SS) and the pelvic tilt (PT). SS and PT vary based on pelvic position, while PI is a fixed parameter (Image reproduced with permission from Medtronic. Radiographic Measurement Manual. Memphis, TN: Medtronic Sofamor Danek; 2004)

5.3 Pelvic Tilt

Pelvic tilt (PT) is defined as the angle subtended by a line drawn from the midpoint of the sacral endplate to the center of the bicoxofemoral axis and a vertical plumb line extended from the bicoxofemoral axis (Fig. 5.1) [6]. When the spine tilts forward (age-related change, sagittal imbalance, loss of lordosis, increase of kyphosis), one way to maintain the spinopelvic alignment is to retrovert the pelvis with increase in PT to maintain an economic posture and to keep the spine as vertical as possible. In a review of 125 cases involving adults with spinal deformity by Schwab et al, there was a significant correlation between HRQOL measures and PT [13]. A high PT is indicative of pelvic retroversion in an attempt to compensate for sagittal-plane deformity, and it compensates for decreased LL (Fig. 5.2) [13]. While PT is an important parameter and does correlate with HRQOL, it should also be remembered that PT is a posture-dependent measurement [6, 13]. Correction of deformity by performing an osteotomy without accounting for an increased PT has the potential to result in incomplete correction of positive sagittal imbalance and persistent clinical symptoms of sagittal imbalance [7]. Pelvic realignment should attempt to obtain a postoperative PT < 20° [19]. PT realignment restores appropriate femoral-pelvic-spinal alignment required during efficient ambulation. This parameter independently has been shown to correlate to impairment in walking tolerance; therefore, it should be considered in surgical planning [6, 13, 15].

Fig. 5.2

Schematic diagram demonstrating for a given structural deformity, how pelvic retroversion compensates for spinal deformity. Left, no pelvic retroversion and high sagittal vertical axis (SVA). Middle, moderate pelvic retroversion and SVA. Right, high pelvic retroversion and no SVA

5.4 Sacral Slope

Sacral slope (SS) is defined as the angle subtended by a line drawn along the endplate of the sacrum and a horizontal reference line extended from the posterior superior corner of S1 (Fig. 5.1) [23]. A mathematical relationship exists such that PI is the sum of PT and SS (PI = PT + SS) [5–7, 19, 23]. As PT increases, the SS decreases because the sacrum assumes a more vertical position about the femoral head axis (pelvic retroversion) [6].

5.5 Lumbar Lordosis

Lumbar lordosis (LL) is measured from the superior endplate of L1 to the superior endplate of S1 and plays an important role in maintenance of upright posture (Fig. 5.3) [13]. Loss of lumbar lordosis or flat back syndrome has been associated with clinical symptoms of back pain and inability to maintain upright posture [24]. Normal values of LL have been described for the adult population and typically range from 40° to 60°. However, the role of pelvis cannot be underestimated in influencing the LL, since every individual has an LL which is dependent on the PI [11, 17, 23, 25]. A study by Duval-Beaupère and colleagues demonstrated that there is a relationship between the LL and PI and that relationship must be maintained in order to optimize the spinopelvic balance [22]. A larger-than-normal PI needs to be balanced with a larger-than-normal SS and LL. Although the spine can be balanced even with a lower LL as compared to PI, the PT is often elevated in that case and signifies a sign of sagittal imbalance, highlighting the complex role the pelvis can play in determining the overall spinal balance [10].

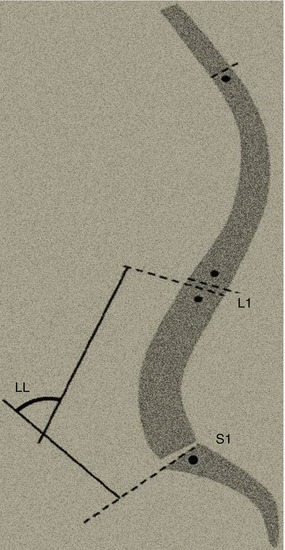

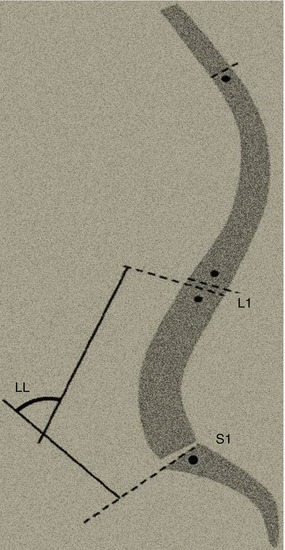

Fig. 5.3

Sagittal spinal parameters. Lumbar lordosis (LL) measured from the superior endplate of L1 to the superior endplate of S1

5.6 Pelvic Obliquity

Pelvic obliquity is a coronal plane parameter which often plays a crucial role in surgical planning. Pelvic obliquity is estimated by measuring the angle formed between a horizontal reference line and a line drawn between the 2 inferior points of the sacral ala on an anteroposterior radiograph (Fig. 5.4) [7]. Pelvic obliquity can be a result of leg length discrepancy from congenital or acquired conditions or from sacropelvic deformity, either of which may produce a compensatory lumbar curve to balance the spine. Correction of this lumbar curve without correction of the underlying pelvic obliquity may lead to coronal decompensation. Similarly, pelvic obliquity can be secondary (e.g., resulting from attempts to compensate for a spinal scoliotic curve), and in these cases, the curve correction strategies must be of sufficient magnitude to allow the pelvis to relax in the coronal plane following surgery. All patients should be evaluated clinically and radiographically for a leg length discrepancy, and if one is identified, the patient should be reevaluated both clinically and radiographically after fitting with a shoe lift to assess how the spine and pelvis respond to correction of the discrepancy. Patients with a flexible curve due to pelvic obliquity as a result of a leg length discrepancy may respond well to the addition of a shoe lift only or surgical treatment of the leg length discrepancy. If the spinal curve is rigid, it will not correct after the addition of a shoe lift, and surgical planning should take this into account.

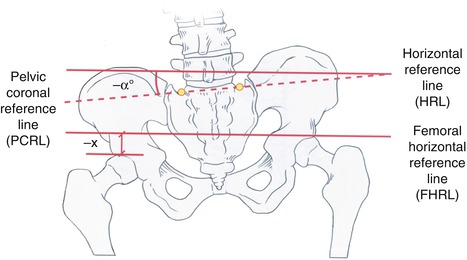

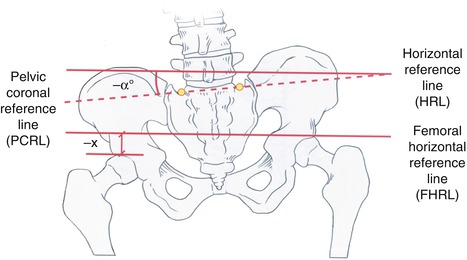

Fig. 5.4

Illustration showing measurement of pelvic obliquity (Image reproduced with permission from Medtronic. Radiographic Measurement Manual. Memphis, TN: Medtronic Sofamor Danek; 2004)

5.7 The Spinopelvic Relationship and Pelvic Translation

Initially, treatment of scoliosis commonly remained restricted to correction of LL and thoracic kyphosis (TK). Recently, several studies have underscored the importance of pelvic morphology in the standing balance in normal adults and children, particularly through effect on LL [8, 9, 11, 12, 26]. It has been suggested that parameters across adjacent zones of the spinopelvic axis (pelvis/lumbar spine; lumbar spine/thoracic spine) are interdependent. These relationships result in the sagittal balance of an individual and the use of compensatory mechanisms. It has been shown that the center of mass of the standing person should be balanced within a narrow relationship to the feet for all subjects (adult patients with spinal deformity and asymptomatic adult subjects) as described by Dubousset’s cone of economy concept [20]. In order to maintain the gravity line, it is evident that spinal deformity will lead to recruitment of balancing mechanisms [12]. One of the ways to measure this is to analyze the PT which indirectly measures the pelvic location regarding the heel line and increases when the sagittal vertical axis (SVA) increases to shift the pelvis posteriorly to maintain the overall balance [6]. These findings confirm the critical role of the pelvis in maintaining balance of the spinopelvic axis.

5.8 Clinical Relevance

It has been shown recently in a number of studies that proper sagittal alignment is the single most important factor affecting outcome for adults undergoing spinal deformity surgery [4, 19, 27]. Patients with spinal deformity with a positive sagittal alignment and inadequate LL have worse physical and social function, self-image, and pain scores [4]. While clinically effective, one of the shortcomings of the sagittal balance concept is that it does not address how balance should be achieved. This is where the concept of spinopelvic balance impacts adult spinal deformity surgery. Spinopelvic balance is based on the concept that there exists a normal, harmonious relationship between the pelvis and the spine [7–9, 11, 12, 26]. Restoring this relationship during adult spinal deformity correction may play an important role in determining the surgical outcomes of these patients, independent of sagittal balance. The results of a large study by Lafage et al. demonstrated that pelvic position, measured by PT, correlated with HRQOL measures in adult patients with spinal deformity [6]. Additionally, the abnormally high values for PT reflect pelvic retroversion, which is a compensatory mechanism for sagittal imbalance. This may affect the surgical decision on osteotomy type and location, as well as how and where correction is achieved along different segments of the spine [7]. Spinopelvic balance should be differentiated from sagittal balance; the latter describes the overall sagittal-plane relationship between spine and the pelvis, while the former describes how the components of the sagittal plane, the regional curves, affect and relate to each other. Vaz et al., [14] noted that the PI remains constant, while LL, TK, SS, PT, and knee position all vary. PI, which is constant in each individual, dictates the position of the sacrum, which is balanced by the degree of LL, which then impacts the amount of TK. Recently, a new classification system has been developed for adult deformity, the SRS-Schwab classification, which incorporates spinal and pelvic parameters with very high interobserver and intraobserver reliability and might be useful for classifying this group of patients [28].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree