32 Lumbosacral Plexopathy

Anatomy

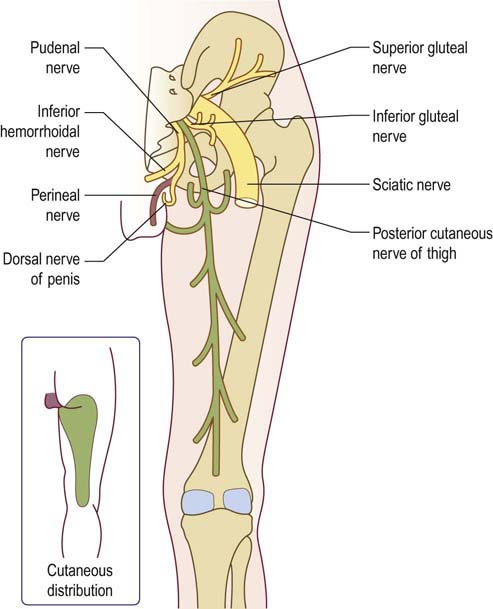

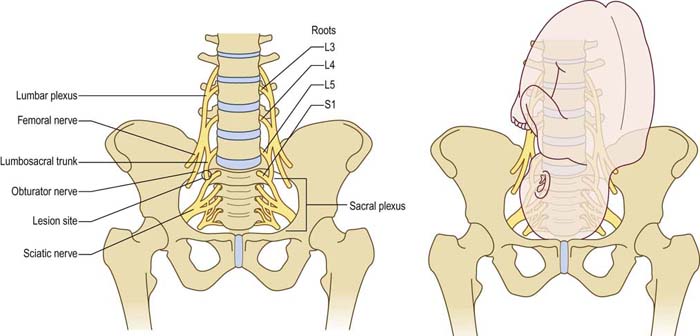

The lumbosacral plexus is usually thought of anatomically as consisting of an upper lumbar plexus and a lower lumbosacral plexus (Figure 32–1).

FIGURE 32–1 Anatomy of the lumbosacral plexus.

(From Hollinshead, W.H., 1969. Anatomy for surgeons, volume 2: the back and limbs. Harper & Row, with permission, New York.)

Lumbar Plexus Nerves

Lateral Femoral Cutaneous Nerve of the Thigh

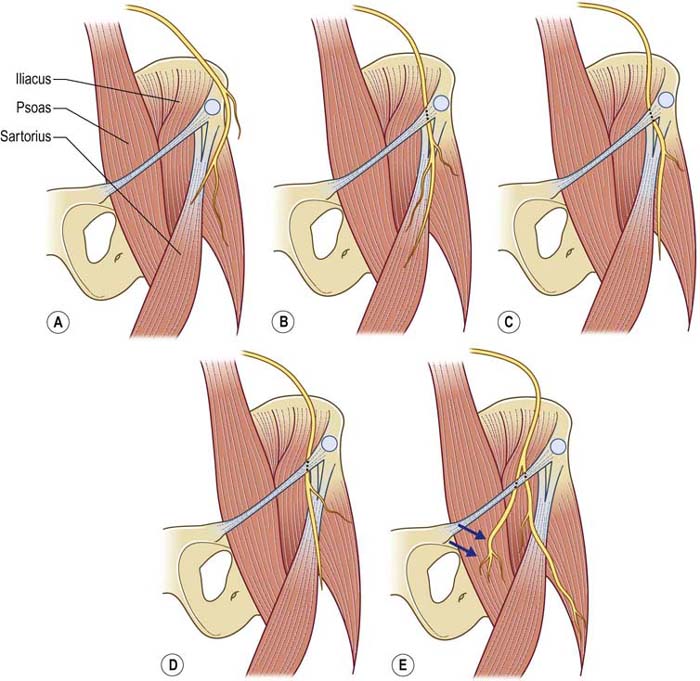

The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) is a pure sensory nerve that is derived from the L2–L3 roots and emerges laterally from the psoas muscle, and then crosses obliquely toward the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) where it passes under the inguinal ligament. It is here at the ASIS and inguinal ligament that the nerve is susceptible to injury and compression. The average distance between the inguinal ligament and the point at which the LFCN emerges distally from the underlying fascia is 10.7 cm with a range of 10–12 cm. At this point, the nerve typically then divides into anterior and posterior branches that supply sensation to a large oval area of skin over the lateral and anterior thigh. Among individuals, there can be significant anatomic variation to where the nerve crosses in relationship to the ASIS and the inguinal ligament (Figure 32–2).

FIGURE 32–2 Anatomic variations in the course of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve.

(Adapted with permission from Aszmann, O.C., Dellon, E.S., Dellon, A.L., 1997. Anatomical course of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve and its susceptibility to compression and injury. Plast Reconstr Surg 100, 600–604.)

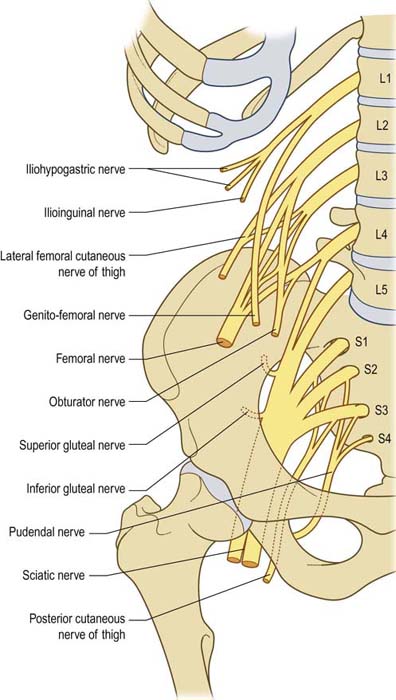

Lower Lumbosacral Plexus Nerves

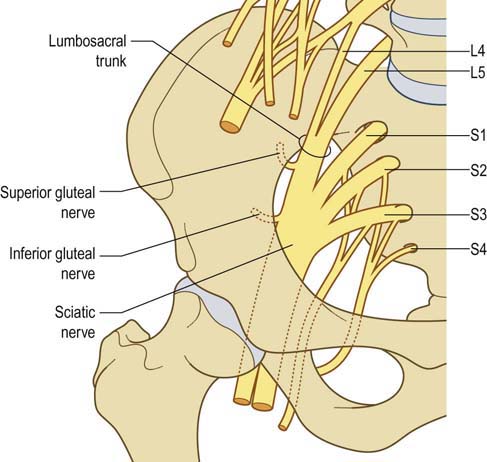

The lower lumbosacral plexus is formed primarily from the L5–S3 roots, with an additional component from the L4 root. This L4 component joins the L5 root to form the lumbosacral trunk (Figure 32–3), which then descends below the pelvic outlet to join the sacral plexus. The remainder of the lower extremity nerves are derived from the lower lumbosacral plexus.

FIGURE 32–3 Lumbosacral trunk: the site of injury in postpartum lumbosacral plexopathy.

(Adapted from Haymaker, W., Woodhall, B., 1953. Peripheral nerve injuries. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, with permission.)

Superior Gluteal Nerve

The superior gluteal nerve (Figure 32–4), derived from L4–L5–S1 fibers, leaves the greater sciatic foramen to supply muscular innervation to the tensor fascia latae, gluteus medius, and gluteus minimus muscles (hip abduction and internal rotation). This nerve usually carries no cutaneous sensory fibers.

Inferior Gluteal Nerve

The inferior gluteal nerve (Figure 32–4), derived from L5–S1–S2 fibers, supplies only the gluteus maximus muscle, which subserves extension of the hip joint.

Posterior Cutaneous Nerve of the Thigh

The posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh (Figure 32–4) is derived principally from the S2 root but also has a component from S1 and S3. It leaves the pelvis adjacent to the sciatic nerve to supply sensation to the lower buttock and posterior thigh. Given its proximity, traumatic injuries to the sciatic nerve commonly damage this nerve as well.

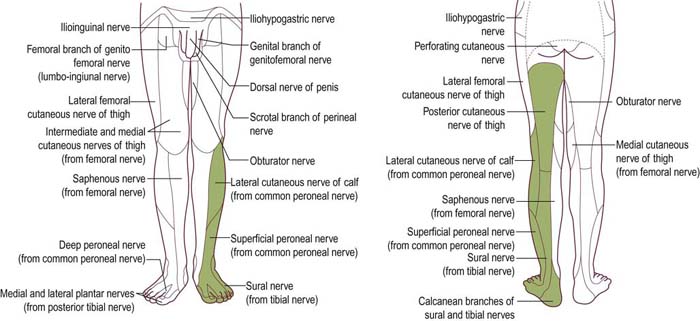

Clinical

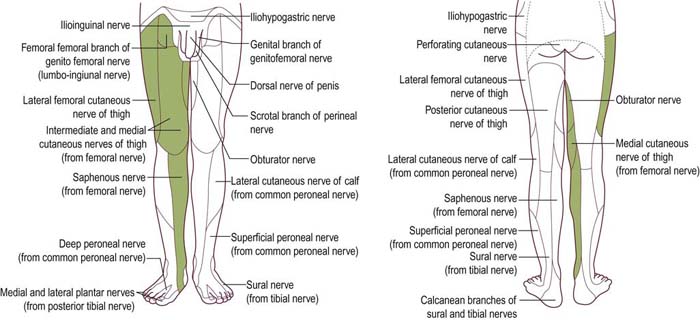

Lumbosacral plexus lesions usually are divided clinically into those affecting the upper lumbar plexus and those affecting the lower lumbosacral plexus, analogous to the underlying anatomic division. Lumbar plexopathies affect predominantly the L2–L4 nerve fibers, resulting in weakness of the quadriceps, iliopsoas, and hip adductor muscles (femoral and obturator nerves). The knee jerk is frequently depressed or absent. Pain, if present, usually is located in the pelvis with radiation into the anterior thigh. Sensory loss and paresthesias occur over the lateral, anterior, and medial thigh and may extend down the medial calf (Figure 32–5).

FIGURE 32–5 Sensory abnormalities in lumbar plexopathy.

(Adapted from Haymaker, W., Woodhall, B., 1953. Peripheral nerve injuries. WB Saunders, Philadelphia.)

Lesions of the lower lumbosacral plexus predominantly affect the L4–S3 nerve fibers. Patients describe a deep boring pain in the pelvis that can radiate posteriorly into the thigh with extension into the posterior and lateral calf. The ankle jerk may be depressed or absent. Sensory symptoms and signs may be seen over the posterior thigh and posterior-lateral calf and in the foot (Figure 32–6). Proximally, weakness may be present in the hip extensors (gluteus maximus), abductors and internal rotators (gluteus medius and tensor fascia latae). In the leg, weakness may occur in the hamstrings, as well as in all muscles supplied by the peroneal and tibial nerves. Nerve fibers destined for the peroneal nerve often are preferentially affected in lumbosacral plexopathies, similar to the preferential involvement of peroneal nerve fibers seen in sciatic nerve and L5 root lesions. Accordingly, patients may present with footdrop and sensory disturbance over the dorsum of the foot and lateral calf. In some cases, the pattern of weakness and numbness may be difficult or impossible to differentiate clinically from an isolated lesion of the common peroneal nerve. It is in such cases that electrodiagnostic studies are crucial.

Etiology

Similar to diseases of the nerve roots, lumbosacral plexopathies can be divided into those caused by structural and those caused by nonstructural lesions (Box 32–1). Structural lesions include pelvic tumors, hemorrhage, aneurysms, endometriosis, and trauma. Among nonstructural causes of lumbosacral plexopathy, the most common is diabetes mellitus. Known also as proximal diabetic neuropathy or plexopathy, diabetic amyotrophy classically affects the lumbar plexus. Lumbosacral plexopathy can also occur on a nonstructural basis from radiation damage, usually in the context of prior treatment for a pelvic, abdominal, or spinal tumor. In addition, the lumbosacral plexus may be injured during pelvic or orthopedic surgery, especially when retractors are used. Other nonstructural causes of lumbosacral plexopathy include inflammation, infarction, and postpartum injuries.

Common Lumbosacral Plexopathies

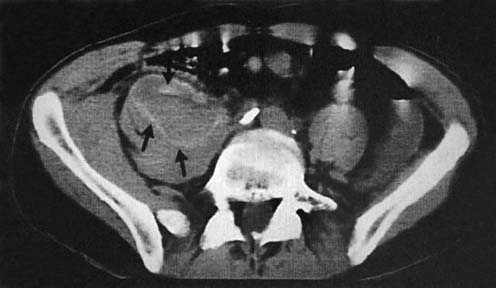

Retroperitoneal Hemorrhage

Retroperitoneal hemorrhage is most commonly seen as a complication of anticoagulation, either with low molecular weight heparin (e.g., enoxaparin), unfractionated heparin, or warfarin, but it may also occur in the setting of hemophilia or as a result of an aortic aneurysm rupture. Such hemorrhages usually are located within the psoas muscle itself, where they can compress the lumbar plexus (Figure 32–7). Patients present acutely with significant pain and often hold the hip flexed and slightly externally rotated. Although the entire lumbar plexus is compressed, the major neurologic deficit usually is in the femoral nerve territory, with weakness of hip flexion and knee extension and a reduced or absent knee jerk. However, close examination often reveals some dysfunction beyond the femoral distribution, either in the obturator or lateral femoral cutaneous nerve territories, or both.

Postpartum Plexopathy

The mechanism of injury likely involves compression of the fetal head against the underlying pelvis and lumbosacral plexus (Figure 32–8). Postpartum lumbosacral plexopathy results primarily from compression of the lumbosacral trunk. These are the fibers from the L4 and L5 roots, which join together to descend into the pelvis to reach the sacral plexus. When the lumbosacral trunk crosses the pelvic outlet, the fibers lie exposed (no longer protected by the psoas muscle) as they rest against the sacral ala near the sacroiliac joints. At this point, the fibers are most exposed and susceptible to compression. The origin of the superior gluteal nerve lies close by and may also be compressed. The fibers that eventually form the peroneal division of the sciatic nerve lie posteriorly, closest to the bone, and are more vulnerable to compression than the tibial division fibers. Accordingly, peroneal fibers are often most affected, with some women presenting with a postpartum footdrop, not infrequently misdiagnosed as peroneal palsy at the fibular neck.

FIGURE 32–8 Postpartum lumbosacral plexopathy.

(From Katirji, B., Wilbourn, A.J., Scarberry, S.L., et al., 2002. Intrapartum maternal lumbosacral plexopathy: foot drop during labor due to lumbosacral trunk lesion. Muscle Nerve 26, 340–347. With permission.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree