Malnutrition, Malabsorption, and B12 and Other Vitamin Deficiencies

Rebecca Traub

Laura Lennihan

INTRODUCTION

Malnutrition and malabsorption lead to isolated and multiple nutritional deficiencies with neurologic manifestations that are ascribed to lack of vitamins or other essential nutrients. An excess of certain vitamins or minerals may also cause neurologic syndromes. Obesity and caloric excess also contribute directly and indirectly to neurologic health status. The wide range of neurologic complications of obesity and dietary excess including ischemic stroke, diabetic neuropathy, and degenerative disease of the spine are covered elsewhere in this text. Treatments for the epidemic of obesity have also led to nutritional disorders and neurologic disease.

Although this chapter describes typical syndromes associated with specific vitamin deficiencies, it should be noted that in clinical practice, vitamin deficiency and malnutrition are often multifactorial with multiple deficiencies occurring together to lead to clinical symptoms and signs.

CAUSES OF NUTRITIONAL DEFICIENCIES

Nutritional deficiency may occur due to inadequate dietary intake or impaired absorption related to intrinsic or iatrogenic gastrointestinal disorders. In developing countries, inadequate nutritional intake is often due to inadequate access to food and natural sources of vitamin and minerals. In developed or industrialized countries, causes of impaired intake may include alcoholism, eating disorders, or other causes of severely restricted dietary intake. Alcohol abuse is a major cause of malnutrition and is associated with numerous neurologic syndromes, the pathophysiology of which may be direct toxicity of ethanol, single or multiple vitamin deficiencies, or a combination. Another common cause of malnutrition is anorexia nervosa. Severely reduced caloric intake related to eating disorders often causes neuropathy, myopathy, and other syndromes related to multiple vitamin deficiencies.

Malabsorption may arise for any of several reasons, both intrinsic and iatrogenic. Bowel diseases causing malabsorption include inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, and disorders of pancreatic enzyme function. In patients with these disorders, neurologic abnormalities seem to be disproportionately frequent. Alone or in combination, there may be evidence of myopathy, sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy, and degeneration of corticospinal tracts and posterior columns and cerebellum. Optic neuritis, atypical pigmentary degeneration of the retina, and dementia are less common signs of malabsorption. Bariatric surgery to treat obesity and its associated complications typically involves restricting gastric volume. Neurologic complications are uncommon but typically are attributed to a combination of malabsorption and hyperemesis resulting in multivitamin deficiency state. Vitamin and mineral supplementation is routinely instituted after bariatric surgery to prevent such complications.

VITAMIN DEFICIENCY AND EXCESS SYNDROMES

Although many presentations of neurologic disorders related to malnutrition are attributed to deficiencies of multiple vitamins and minerals occurring together, there are particular syndromes and neurologic disorders that are typically described with specific deficiencies (Tables 123.1 and 123.2). Oversupplementation of some vitamins or minerals may also lead to neurologic disorders. In the following sections are descriptions of some of these more commonly seen syndromes.

VITAMIN B12 (COBALAMIN) DEFICIENCY

Pernicious anemia, caused by vitamin B12 deficiency, includes the triad of anemia, neurologic symptoms, and atrophy of the epithelial surface of the tongue. The term combined degeneration of the spinal cord to describe the nervous system consequences of B12 deficiency was introduced around 1900. Replacement therapy began in the 1920s with dietary liver and parenteral liver extract in 1948, the year that vitamin B12 was identified. B12 deficiency continues to be common, with increased risk with older age related to atrophic gastritis, decreased dietary intake, and use of medications that interfere with acid secretion.

Physiology of B12 Metabolism

Cobalamin is synthesized only in specific microorganisms, and animal products are the sole dietary source. Gastric acid is needed for peptic digestion to release the vitamin from proteins. The freed B12 is bound by R proteins and then by gastric intrinsic factor, a glycoprotein produced by gastric parietal cells, which is needed for transport of B12 and which is absent in people with pernicious anemia. The combined intrinsic factor-cobalamin complex is transported across the terminal ileum and binds to transcobalamin, which then enters cells for use in metabolic processes.

TABLE 123.1 Neurologic Syndromes Attributed to Vitamin or Mineral Deficiency | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 123.2 Neurologic Syndromes Attributed to Vitamin or Mineral Excess | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pathobiology of B12 Deficiency

About 80% of adult-onset pernicious anemia is caused by lack of gastric intrinsic factor secondary to atrophic gastritis. The disorder is thought to be autoimmune in origin because antibodies to gastric parietal cells are found in 90% and antibodies to intrinsic factor occur in up to 76% of people with pernicious anemia. Pernicious anemia also coexists with other autoimmune diseases. In those with normal intrinsic factor, the vitamin is not absorbed because of jejunal diverticulosis, tropical or celiac sprue, or loss of the stomach or ileum by surgical resection. Proton pump inhibitors and H2-blocker medications to treat gastroesophageal reflux or peptic ulcer disease also can cause B12 deficiency. Chronic recreational or occupational exposure to nitrous oxide can interfere with cobalamin metabolism and cause neuropathy or combined system disease. Long-term metformin therapy for diabetes mellitus can also lead to B12 deficiency through interference with calciumdependent ileal membrane function.

Pathology of B12 Deficiency

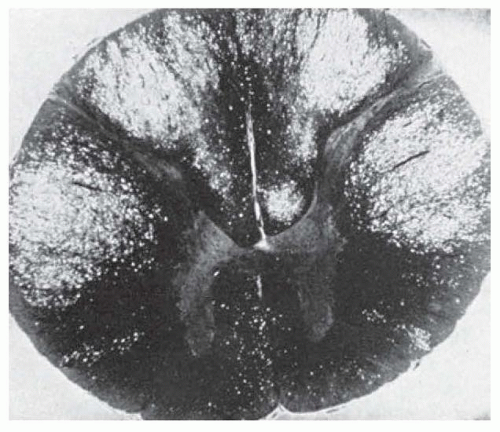

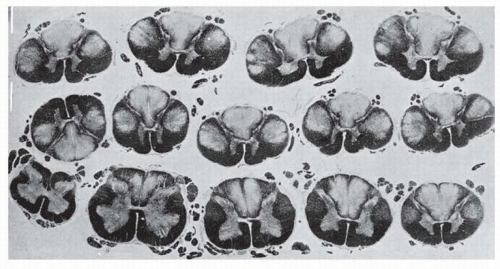

In the spinal cord, white matter is affected more than gray. Symmetric loss of myelin sheaths occurs more often than axonal loss; changes are most prominent in the posterior and lateral columns (combined system disease; Figs. 123.1 and 123.2). The thoracic cord is affected first and then the process extends into the cervical or lumbar spinal cord. Patchy demyelination may be seen in the frontal white matter, correlating with cognitive clinical symptoms.

FIGURE 123.1 Subacute combined degeneration. Sections of spinal cord at various levels showing segmental loss of myelin, which is most intense in the dorsal and lateral columns. |

Clinical Features

Today, most people with B12 deficiency are probably asymptomatic.

If the deficiency persists, symptoms may be those of anemia, neurologic disorder, or other problems such as vitiligo, sore tongue, or prematurely gray hair. About 40% of all patients with B12 deficiency have some neurologic symptoms or signs, and these are often the first or most prominent manifestations of the disease. Usually, there are features of both myelopathy and peripheral neuropathy. The most common symptom is acroparesthesia—burning and painful sensations that affect the hands and feet. There may be sensory ataxia due to loss of proprioception. Memory loss, visual loss (owing to optic neuropathy), orthostatic hypotension, anosmia, impaired taste (dysgeusia), sphincter symptoms, and impotence are other symptoms and signs that have been described. B12 levels should be checked in all people undergoing evaluation of cognitive impairment, as it is a treatable cause of memory loss.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis rests on demonstration of serum levels of vitamin B12 under 200 pg/mL, but low-normal values (200 to 350 pg/mL) may be found in people who respond to therapy. Some people with low values are not deficient, and additional tests may be useful. Both methylmalonic acid and homocysteine accumulate when there is impairment of cobalamin-dependent reactions; both metabolites are abnormally increased in serum in more than 99% of patients with true cobalamin deficiency. There are limitations to these tests in certain populations, with elevated homocysteine in hereditary homocysteinemia and elevated methylmalonic acid in patients with renal failure. Pernicious anemia, which often underlies B12 deficiency, is best assessed with intrinsic factor antibodies. Sensitivity of these antibodies is only 50% to 70% but specificity is nearly 100%. Antiparietal cell antibodies are more sensitive but less specific.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree