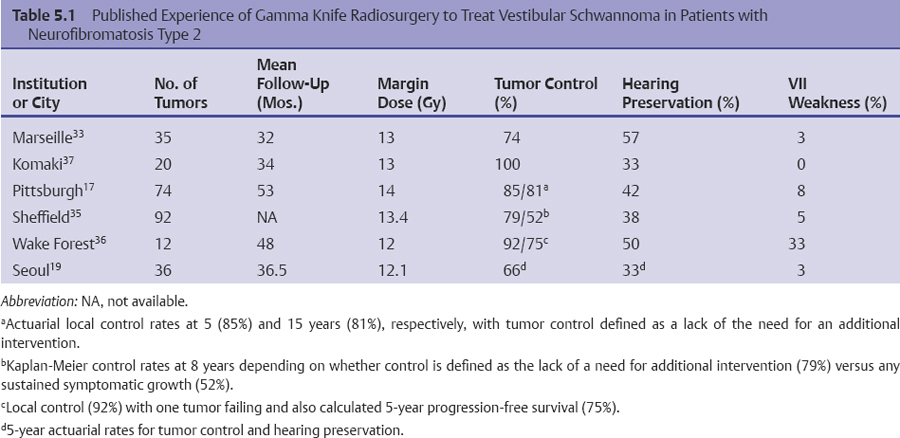

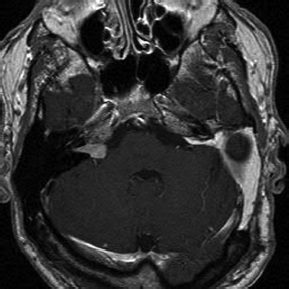

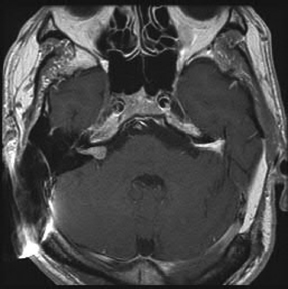

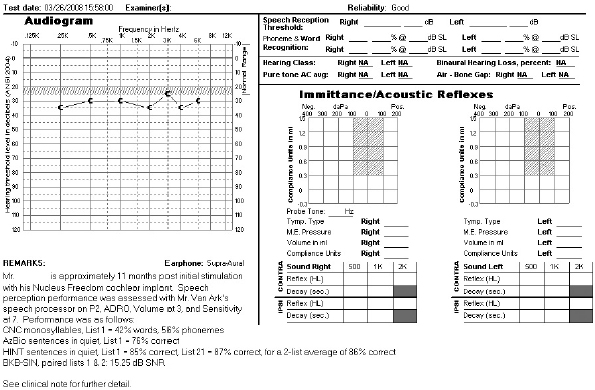

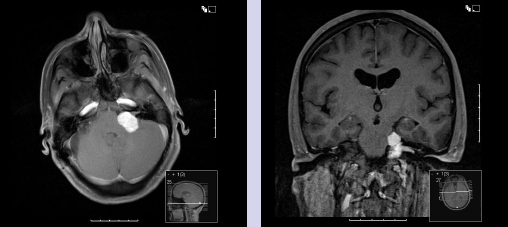

Chapter 5 Case A 45-year-old woman with neurofibromatosis type 2 previously underwent resection of a right giant acoustic tumor and is deaf in the right ear. In the left ear, she currently has serviceable hearing with 75% discrimination at 30 dB. Participants Microsurgical Removal of Acoustic Tumors in a Single Hearing Ear of Patients with Neurofibromatosis Type 2: Madjid Samii and Venelin M. Gerganov Stereotactic Radiosurgery for an Acoustic Neuroma in the Only Hearing Ear: Michael J. Link, Colin L.W. Driscoll, and Bruce E. Pollock Conservative Treatment of Acoustic Tumors in Patients with a Single Hearing Ear: Donlin M. Long Moderator: Preserving Hearing in the Last Hearing Ear of Patients with Neurofibromatosis Type 2: Stephen J. Haines The treatment of patients with neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) represents one of the most difficult challenges in neurosurgery. The patient’s lifelong propensity to develop new tumors in the central nervous system predetermines the impossibility of definitive cure for these patients.1 Treatment is focused on prolonging life, preserving or restoring neurologic function, and maintaining the patient’s quality of life.2–4 Vestibular schwannomas associated with NF2 differ in several ways from sporadic unilateral tumors, and the major concerns are the disabling consequences of acquired deafness. In the presented case, the giant vestibular schwannoma on the right side was initially removed. The patient has useful hearing on the left side and a tumor in the left cerebellopontine angle with the characteristics of a vestibular schwannoma. The lesion is centered in the internal auditory canal and forms an acute angle with the posterior surface of the petrous bone. It extends into the internal auditory canal and shows homogeneous contrast enhancement. The sagittal image shows that the tumor has a significant caudal extension, which has been correlated with a worse outcome regarding at least the facial nerve function.5 In such cases, optimal results are obtained if the treatment is individualized and guided by the attitude and expectations of patients and their families. Decision making depends on several factors related to the tumor and to the clinical and psychological condition of the patient. The options are initial observation or early active treatment. Close collaboration with patients and their families is essential. The major issue is whether the patient is willing to take the risk of complete hearing loss from early active treatment or prefers to postpone treatment until hearing is lost through progression of the disease. The possibility of preserving hearing depends on the size of the tumor, the patient’s preoperative hearing level, and the quality of the brainstem auditory evoked potentials (BAEPs). With regard to the first two factors in the current case, the chance of preserving functional hearing is approximately 50%. But there is no information about the quality of BAEP, an examination we perform routinely. During surgery, BAEP monitoring provides essential feedback about the function of hearing pathways every 30 to 90 seconds.6,7 Changes from traction or injury of the cochlear nerve and the interruption of vascular supply or compression of the brainstem are readily detected. A loss of wave V is most frequently associated with deafness, either temporary or permanent, but this loss is usually preceded by changes in waves I and III. This information enables the surgeon to modify the approach accordingly, for example, the degree of cerebellar retraction. When surgery is done on the only hearing side, the operation may even be interrupted. If the BAEP is of low quality, with loss of waves or considerable prolongation of intervals, this feedback is not available. In such a case, we would not recommend early surgery. Once the decision for active treatment is made and a good BAEP wave form is available, the next task is to choose the best treatment option: surgery or radiosurgery. Our experience has shown that surgery of vestibular schwannomas via the retrosigmoid approach leads to the best outcome, especially with respect to hearing.7 The advantages of this approach have been described in multiple publications.8–10 Placing the patient in the semi-sitting position allows the surgeon to use both hands for tumor dissection because there is no need for constant suction. The assistant irrigates continuously with saline, which obviates the need to coagulate during tumor removal. To preserve hearing, the structures of the inner ear must be preserved during drilling of the internal auditory canal. A careful study of thin-slice bone-window computed tomography scans of the pyramid before surgery allows the surgeon to plan the extent of safe bone removal. If the location of the inner ear precludes wide opening of the internal auditory canal, an angled endoscope can be used to inspect the most lateral portion of the canal. Another critical issue is the dissection technique. The nerve should always be dissected from the tumor in the arachnoid plane, and dissection begins only after sufficient debulking of the tumor mass. The stretching of neural structures in one direction for a long time should be avoided. These steps should be constantly related to the BAEP input and modified accordingly. If the patient is in the semi-sitting position, coagulation is required only in cases of major bleeding.8 Vestibular schwannomas associated with NF2 differ from sporadic vestibular schwannomas and are more challenging for the surgeon.11,12 Approximately 40% of them are multilobular, and the nerves and vessels may pass between the tumor lobules. The tumor can infiltrate the fibers of individual nerves, a phenomenon seldom found in unilateral tumors. In these cases, subtotal tumor removal may be done to prevent functional deficits. When the BAEPs are unstable and even slight microsurgical maneuvers are followed by severe deterioration of the waveform, attempting complete tumor removal may endanger the patient’s hearing. In this case, the surgeon may choose partial tumor removal and decompression of the cochlear nerve in the internal auditory canal during surgery. The senior author (M.S.) used this strategy in 23 patients, which led to long-term preservation of hearing in 15 of them.3 If the patient decides against surgery, the tumor should be followed and removed when hearing loss occurs or tumor progression leads to serious neurologic symptoms. For such patients, the surgeon should plan to restore hearing with an auditory implant during the same surgery or several weeks later. Such central auditory prostheses—the auditory brainstem implants, or, more recently, the auditory midbrain implants—help patients receive environmental sounds and enhance their lip-reading ability for better communication.13–16 Radiotherapy is another treatment option for the patient presented here. Published series show that it leads to tumor control in up to 81% of patients at 10 years.17,18 The rate of hearing preservation is 33 to 43%, although some deterioration occurs during the ensuing years. In a recent study, Phi and colleagues19 have shown that the rates of actual serviceable hearing preservation fall from 50% in the first year to 45% in the second year and to 33% in the fifth year. Postirradiation edema may lead to a transient increase in the tumor volume. When tumors compress the brainstem, as in the presented case, this possibility and the related risks should also be considered. In patients with vestibular schwannomas associated with NF2 on the only hearing side, an additional advantage of surgery compared with radiosurgery is the possibility of interrupting tumor removal if the BAEP changes and, thus, preserving the available hearing. In our experience, radiosurgery is best reserved for patients who have particularly aggressive tumors, those with medical contraindications for microsurgery, patients who refuse surgery, and the elderly.3,4,11 Over the past 35 years, the senior author (M.S.) has operated on more than 175 patients with NF2; the total number of vestibular schwannoma surgeries in these patients was 225. Total removal was achieved in 86% of the operated tumors. In the remaining 14%, total removal was impossible because of infiltration of the nerves or the risk of functional loss. Hearing was preserved in 65% of patients with useful preoperative hearing. In patients with vestibular schwannomas of a size similar to the one presented here, the cochlear preservation rate was 82% and the hearing preservation rate was 52%. Under consideration is the case of a 45-year-old woman with NF2 who has previously undergone successful resection of a giant right acoustic neuroma and who has no hearing in that ear. As shown by the single axial and coronal images available, she has a left acoustic neuroma of 2.5 cm (the greatest posterior fossa diameter measured parallel to the petrous temporal bone). She is reported as having a speech discrimination score of 75% at 30 dB on the left. Thus, she likely has American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) class A hearing in only her left ear.20 Following the guiding principles for NF2 patients of preserving the quality of life and conserving or rehabilitating function, especially hearing, we discuss our approach to similar patients and the advisability of stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) to treat her left acoustic neuroma. In general, intervention for a lesion involving the only hearing ear can be considered in the following circumstances: 1. The predicted natural history of the disease is relatively rapid loss of the remaining hearing. 2. Substantial or life-threatening brainstem compression has developed. 3. Intervention may improve hearing or carries a relatively low risk of hearing loss.21 But none of these criteria apply to this patient at this time. We would have placed an auditory brainstem implant on the right side when the giant right acoustic neuroma was removed, assuming that the tumor was so large there was no hope of preserving the cochlear nerve to allow placement of a cochlear implant. We would then follow the left acoustic neuroma in the only hearing ear with biannual magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and audiology examinations, and intervene if hearing progressively deteriorates or the tumor shows sustained growth. Lars Leksell22 is deservedly credited with introducing SRS in 1951, and the first published report of SRS to treat an acoustic neuroma appeared in 1971.23 Thus, we have had over 40 years to evaluate the potential, efficacy, and complications of this modality, and the technique and dose-planning software have changed dramatically during this time. In the last 15 to 18 years in particular, tumor marginal doses have been reduced to attempt to preserve cranial nerve function without sacrificing tumor control. In addition, the availability of high-resolution, multiplanar, thin-slice MRI scanning to assist in planning has resulted in more conformal treatment plans. Tumor control rates of 93 to 98% and hearing preservation rates of 33 to 78% have been reported with SRS for sporadic vestibular schwannomas in many large, recently published series.24–30 A comprehensive review of the literature published in 2009, encompassing 5,825 patients in 74 publications, reported an overall hearing preservation rate of 57% after SRS for vestibular schwannoma.31 In this review, a marginal dose of less than 12.5 Gy was the only statistically significant factor for preserving hearing. Neither the patient’s age nor the tumor size was significant. Several groups have found that a maximum dose of less than 4 or 4.2 Gy to the cochlea is associated with better hearing preservation rates after SRS or fractionated radiotherapy,25,26,28,32 whereas at least one group has reported the dose to the cochlear nucleus to be the important prognostic variable.29 Although these data seem encouraging, there is much concern that vestibular schwannomas in patients with NF2 do not respond as well as sporadic vestibular schwannomas to SRS.33,34 There are significantly fewer reports in the literature regarding the use of SRS to treat vestibular schwannomas associated with NF217,19,33–37 (Table 5.1). The largest and most recently reported experience is from Sheffield, England.35 In this study, Rowe and colleagues report on their results in 92 tumors using current techniques (MRI localization) and doses (mean marginal dose of 13.4 Gy). The mean age of the patient at treatment was 29 years. Based on a Kaplan-Meier plot, if failure is defined as the need for an additional procedure, 79% of tumors were successfully controlled at 8 years. However, if a stricter definition of failure is defined as any progressive growth with increasing symptoms possibly attributed to a growing vestibular schwannoma, the control rate falls to 52% at 8 years.35 The tumor volume at the time of treatment was the most significant determinant of failure (p < 0.001), with tumors larger than 10 cm3 correlating to a statistically higher like lihood of failure. Overall, 23 of 61 patients (38%) who had serviceable hearing before treatment maintained their hearing grade, whereas 42% had some deterioration of their hearing, and 20% became completely deaf. Permanent facial weakness occurred in 5% of patients, and 2% developed permanent trigeminal dysfunction related to the SRS.35 Our results at the Mayo Clinic are similar. We treated 29 vestibular schwannomas in 24 patients with NF2 between 1999 and 2007. At a median follow-up of just over 3 years, 20 tumors have remained stable or decreased in volume at the last MRI follow-up, four tumors have shown progressive enlargement at more than one imaging follow-up, and no imaging follow-up could be obtained for five tumors. Depending on the outcome of these last five tumors, we would classify our tumor control rate as 69 to 86%. The affected ear in 15 patients had measurable hearing before SRS and 14 patients were profoundly deaf in the affected ear. Six maintained their pretreatment hearing, seven progressed to class D hearing, and no audiometry follow-up could be obtained for two. Thus, our hearing preservation rate is 46%. Based on our experience and that reported in the literature, we would counsel the patient presented here that, if she elects to have SRS to treat the 2.5-cm vestibular schwannoma in her only hearing ear, there is an 80% chance that she will not require another intervention for that tumor 5 years after treatment. Furthermore, there is a 40% chance of maintaining useful hearing in that ear and a less than 5% risk of any permanent facial weakness or numbness. Stereotactic radiosurgery also offers another potential significant advantage to this patient. If she does lose hearing after treatment, there is still a very high chance that her hearing could be rehabilitated with a cochlear implant.38 We have implanted this device in three patients with NF2 after SRS for a vestibular schwannoma. The mean age of these patients was 68 years, and they had been profoundly deaf in the affected ear for 1 to 10 years before the cochlear implant. The mean tumor volume treated was 1 cm3. All patients experienced a significant restoration of hearing after receiving the cochlear implant. Fig. 5.1 The pretreatment audiogram reveals profound left-sided hearing loss after a prior translabyrinthine removal of a left vestibular schwannoma. There is also severe right-sided hearing loss with a pure tone average of 65 dB. The patient’s word recognition score was 20% at 40 dB. For example, a 64-year-old man had previously undergone translabyrinthine resection of a left vestibular schwannoma in 1989 without complication. He then began to develop significant right-sided hearing loss 10 years later, and by 2007 he had a pure tone average of 65 dB and only 10 to 20% word recognition in the right ear (Fig. 5.1). His MRI showed a 1.1-cm right vestibular schwannoma and postoperative changes from his left-sided surgery (Fig. 5.2). At the last follow-up, 2 years after undergoing SRS and receiving a cochlear implant, his tumor had decreased to 0.8 cm in the posterior fossa diameter (Fig. 5.3), and his cochlear implant was working very well. He was achieving 85 to 87% on the hearing-in-noise test (HINT), which uses sentence testing, and he achieved 42% correct on consonant-vowel-consonant (CNC) word testing. His pure tone average with the cochlear implant was 30 dB (Fig. 5.4). Fig. 5.2 The pretreatment magnetic resonance imaging shows postoperative fat packing from a prior left translabyrinthine surgery and a 1.1-cm right vestibular schwannoma. Fig. 5.3 An MRI 2 years after stereotactic radiosurgery. The tumor has decreased in size by 2 mm in the largest posterior fossa diameter. Our other patients have had similarly good clinical results following cochlear implant after SRS. One of our patients, however, had sustained growth of a tumor after SRS but still had good cochlear implant function despite the tumor growth. Ultimately, the tumor had to be resected and the cochlear implant was removed and converted to an auditory brainstem implant. This device gives the patient environmental sound awareness but does not provide nearly as good hearing as his cochlear implant did. There are three main concerns with treating vestibular schwannomas in NF2 patients with SRS. The first is that it will not be effective, and we have presented the results as reported in the literature with good evidence that NF2 tumors do not respond as well as sporadic ones, but still 80% of the tumors will be controlled at 5 years. Whether this is sufficient in a 45-year-old woman is a difficult decision. A related, valid concern is that, if the treatment does fail and the tumor requires surgical removal, it will be a more difficult operation due to scarring from the radiation. It has indeed been our limited experience that surgery after SRS is more challenging, and other groups have also reported this fact.39,40 A second concern is that hearing rehabilitation with either a cochlear implant or an auditory brainstem implant will be less effective after SRS. This assumption has not been borne out in our experience or in the literature.38,41 Both cochlear and auditory brainstem implants seem equally effective whether the tumor has been surgically removed or treated with SRS. In fact, the chance of getting a functioning cochlear implant, particularly in a patient with a tumor larger than 2.0 cm, is likely much higher after SRS compared with microsurgery because there is no surgical manipulation of the cochlear nerve. Finally, there has been concern that even single-fraction, conformal SRS could induce malignancy in NF2 patients who already have a mutation in a tumor-suppressor gene.44

Management of a Vestibular Schwannoma in a Single Hearing Ear of a Patient with Neurofibromatosis Type 2

Microsurgical Removal of Acoustic Tumors in a Single Hearing Ear of Patients with Neurofibromatosis Type 2

Stereotactic Radiosurgery for an Acoustic Neuroma in the Only Hearing Ear

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree