Management of Cerebral Aneurysms

Etiology

Cerebral aneurysms can occur at any age but are most common in the adult population and more common in females. Aneurysmal rupture occurs most commonly in the fifth decade and has an incidence of approximately 10 in 100,000 persons per year (approximately 27,000 individuals per year in the United States). Cerebral aneurysms arise most commonly in the anterior cerebral circulation. The formation, growth, and rupture of cerebral aneurysms are thought to be caused by multiple factors (Table 13.1), including environmental factors such as smoking and chemical stimulants (for example, cocaine), genetic predisposition and susceptibility factors, family history of aneurysm, systemic medical comorbidities (such as hypertension or hyperlipidemia), and collagen vascular disease, such as Marfan syndrome, adult polycystic kidney disease, and Loeys-Dietz syndrome.

Diagnosis

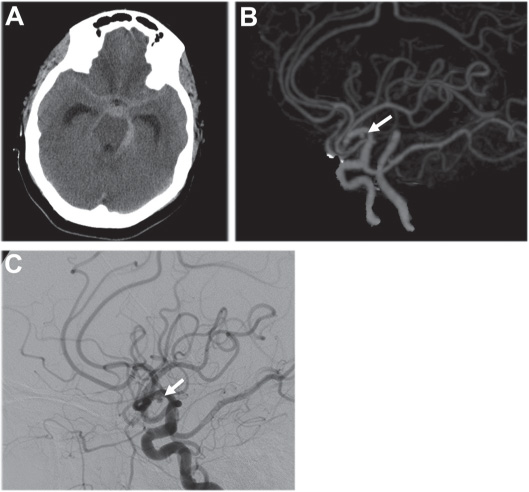

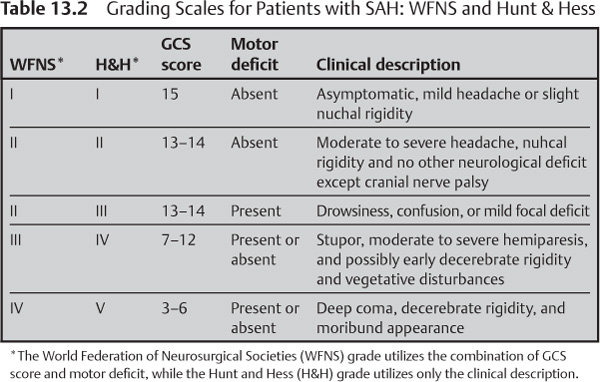

Unruptured cerebral aneurysms are frequently identified incidentally during an evaluation for chronic headaches, ill-defined neurological disorders, tumor, and trauma. Ruptured aneurysms often present with an acute onset of headache, meningismus, photophobia, and in severe cases, coma and death (Fig. 13.1, Table 13.2). Up to 30% of ruptured aneurysm patients are found to have complained of a headache days before, which may have been from a “sentinel” hemorrhage.

Evidence-Based Medicine

There has been a paucity of well-designed clinical studies that have examined cerebral aneurysms, both from a natural history and a treatment perspective. The following reports are the best currently available studies from the literature that examine both the natural history of unruptured aneurysms as well as some differences between microsurgical and endovascular management of cerebral aneurysms.

Table 13.1 Risk Factors for Aneurysm Formation

Smoking |

Hypertension |

Atherosclerosis |

Connective tissue disorders |

Alcohol |

Hemodynamic stresses |

Illicit drugs |

Genetics/family history |

Fig. 13.1 Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. (A) Admission head CT of a patient with sudden-onset headache, nausea, and vomiting demonstrating diffuse, thick subarachnoid hemorrhage, most prominent on the left, with hydrocephalus. (B) CT angiogram and (C) catheter angiogram demonstrating a small MCA aneurysm (arrows).

The International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms-1 (ISUIA-1)1

Purpose

The International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms-1 (ISUIA-1) was designed to establish the natural history of unruptured intracranial aneurysms (retrospective arm) and the risk of surgical clip ligation (prospective arm). There were two groups within each study arm: one (Group 1) had no history of previous subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) and the other (Group 2) did have a history of previous SAH from another aneurysm.

Eligibility

The inclusion criteria selected patients from the United States, Europe, and Canada with unruptured aneurysms and those with a history of SAH from another aneurysm, who presented with headache (HA), central nervous (CN) palsy, stroke, ill-defined spells, mass effect, seizure, brain tumor, or degenerative central nervous system (CNS) disease. Exclusion criteria included fusiform, mycotic, or traumatic aneurysms, aneurysms less than or equal to 2 mm, SAH or intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), no consent to follow-up, or malignant brain tumor.

Results

The average aneurysm size was 10.9 mm (Group 1) and 5.7 mm (Group 2). The rupture risk was predicted by location (for both Group 1 and Group 2) and size (Group 1). A higher rupture risk was observed for larger (Table 13.3), posterior circulation (Table 13.4) aneurysms and for older age (RR = 1.31).

Criticisms

(1) Posterior communicating artery (PCOM) aneurysms were categorized as “posterior circulation” despite originating from the internal carotid artery (ICA), (2) surgical morbidity and mortality were greater than that previously reported (Table 13.5), and (3) the average size of aneurysms in Group 1 was almost twice that of Group 2.

Table 13.3 ISUIA-1: Aneurysm Size and Annual Rupture Risk

| Annual rupture risk | |

Aneurysm size (mm) | Group 1 | Group 2 |

2–10 | 0.05 | 0.5 |

10–24 | <1 | <1 |

25 | 6 | —– |

Table 13.4 ISUIA-1: Relative Risk of Aneurysm Rupture, Based on Location

| Annual rupture risk | |

Location | Group 1 | Group 2 |

Basilar tip | 13.8 | 5.1 |

Vertebrobasilar artery | 13.6 | — |

Posterior communicating artery | 8 | — |

Table 13.5 ISUIA-1: Surgical Morbidity and Mortality

| Annual rupture risk | |

Time after surgery | Group 1 | Group 2 |

30 days | 17.5% | 13.6% |

1 year | 15.7% | 13.1% |

The International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms-2 (ISUIA-2)2

Purpose

The International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms-2 (ISUIA-2) was a prospectively randomized trial designed to assess further the natural history of unruptured intracranial aneurysms and to compare outcomes of surgical and endovascular repair. Enrolled patients were randomized to one of three study arms: (1) prospective observational, (2) surgical clip ligation, and (3) endovascular repair.

Eligibility

The criteria for ISUIA-2 were the same as those for ISUIA-1.

Results

There was increased rupture risk for larger and posterior circulation aneurysms (including PCOM) (Table 13.6), and those less than 7 mm with a previous SAH from another aneurysm (Table 13.7). Patient age greater than or equal to 50 years, posterior circulation, and aneurysm size greater than or equal to 12 mm were predictors of poor surgical outcome. Complete aneurysm obliteration rates were 55% for the endovascular arm (Table 13.8) and 264 aneurysms required additional treatments.

Criticisms

(1) Aneurysms less than 7 mm are reported as having a 0% rupture risk, which is misleading given that most ruptured aneurysms are between 6 and 9 mm; (2) morbidity and mortality were higher for surgical treatment, but the cumulative risk of subsequent procedures for failed initial treatment is not discussed.

Table 13.6 ISUIA-2: 5-year Aneurysm Rupture Risk

| Annual rupture risk | |

Size (mm) | Anterior circulation | Posterior circulation |

2–7 | 0 | 2.6 |

7–12 | 2.6 | 14.5 |

13–24 | 14.5 | 18.4 |

325 | 40 | 50 |

| Annual rupture risk | |

| No SAH history | SAH history |

Anterior | 0 | 1.5 |

Posterior | 2.6 | 3.4 |

Table 13.8 ISUIA-2: Endovascular Aneurysm Obliteration Rates

Obliteration type | Percent |

Complete | 55 |

Incomplete | 24 |

No obliteration | 18 |

The International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT)2

Purpose

The International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) was a prospectively randomized multicenter clinical trial designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of coil embolization versus surgical clip ligation for ruptured aneurysms.

Eligibility

Patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms eligible for either treatment modality were randomized to the surgical or endovascular arm. Those deemed better treated with surgery or coiling were not randomized in this study.

Results

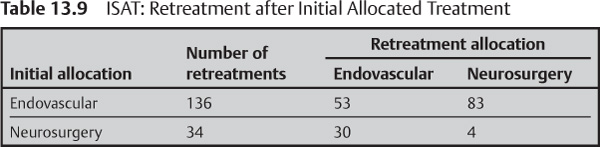

There was a 22.6% RRR (6.8% ARR) at one year in dependency and death after endovascular treatment. A second treatment was required for 136 endovascular and 34 surgical patients; a majority underwent a second treatment using the other modality (Table 13.9). There was statistically no difference in rebleed rates between the two groups, using an intent-to-treat analysis (Table 13.10A).

A | ||

Timing of rehemorrhage | Endovascular | Neurosurgery |

Before first procedure | 14 | 23 |

<30 days after procedure | 20 | 6 |

30 days–1 year | 6 | 4 |

>1 year | 2 | 0 |

TOTAL | 42 | 33 |

| ||

B | ||

Before first procedure | Excluded | Excluded |

<30 days after procedure | 20 | 6 |

30 days–1 year | 6 | 4 |

>1 year | 2 | 0 |

TOTAL | 28 | 10 |

Criticisms

(1) Only 25% of the patients met inclusion criteria for randomization; (2) 93% of aneurysms were less than or equal to 10 mm; (3) 89% were WFNS 1 (63%) or 2 (26%); (4) location was heavily weighted toward the anterior communicating artery (ACOM) and PCOM, limiting generalization of the results to other aneurysm locations (Table 13.11); (5) the number of basilar bifurcation aneurysms was small, suggesting that they were likely better treated with endovascular therapy; and (6) when the number of patients who bled again while waiting for treatment are removed, rebleed rates were actually higher for the endovascular group (Table 13.10B).

Table 13.11 ISAT Distribution of Aneurysm Location

ACOM | 973 |

PCOM | 536 |

MCA | 257 |

BA | 17 |

Abbreviations: ACOM, anterior communicating artery; BA, basilar artery; MCA, middle cerebral artery; PCOM, posterior communicating artery.

Preprocedural Preparation

Unruptured Aneurysms

During preparations for endovascular treatment of an unruptured aneurysm, conditions that predispose the patient to procedural risks must be elicited from the patient (Chapter 6). Pretreatment with antiplatelet agents, required when using vascular reconstruction devices (stents), must also be considered.

Ruptured Aneurysms

In addition to those preparations defined for unruptured aneurysms, aneurysmal SAH patients require additional preparation prior to endovascular treatment. The SAH patient is generally ill and neurologically impaired. Rerupture rates are typically 4% over the first 24 hours, 20% over two weeks, 50% over six months, and then 3% annually. Rerupture is generally lethal. Initial assessment of SAH patients should be done expeditiously (Table 13.12).

Equipment Check List

The nuances of the equipment and techniques can be found elsewhere in this handbook (Chapters 7 and 8). Here we will describe only those details pertinent to aneurysm coiling.

Table 13.12 ABCVs of SAH: Recommendations for Preprocedural Preparation

Assessment | Result | Action |

Airway | Unable to protect airway, GCS£8 | Intubation |

Breathing | Required intubation | Mechanical ventilation (pCO2 35–45) |

Circulation | Hypertension, cardiac ischemia, arrhythmia | Normotensive (SBP 90–130), cardiac enzymes |

Ventricles | Hydrocephalus |