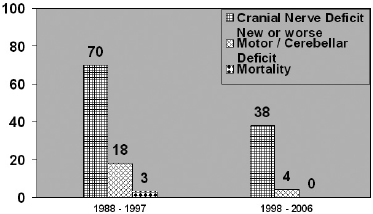

Chapter 3 Case A 50-year-old woman has mild diplopia and trigeminal neuralgia that responded well to medical treatment. Participants Management of Petroclival Meningiomas: The Role of Excision and Radiosurgery: Basant K. Misra Total Removal of Petroclival Meningiomas: Ian F. Dunn, Rami Almefty, and Ossama Al-Mefty Moderator: Management of Petroclival Meningiomas: Total Removal vs. Subtotal Resection and Radio surgery: Kadir Erkmen As meningiomas are potentially curable, their treatment is a gratifying surgical exercise when the tumor is avascular and occurs in the convexity. But when the tumor is firm and arising deep at the base of the skull, it presents one of the most formidable challenges in neurosurgery. Petroclival meningiomas fall in this latter category. For this discussion, clival and petroclival meningiomas are considered as one entity—those meningiomas arising from the upper two thirds of the clivus and those originating at the clivus and petroclival junction medial to the trigeminal nerve.1–3 Up to 1970, petroclival meningiomas were considered inoperable, as only 10 of the 26 patients reported in the literature survived surgery and only one had a total excision.3 Parallel advances in microneurosurgery and the introduction of innovative skull-base approaches in the late 1980s led to a renewed enthusiasm about radical excision of petroclival meningiomas, and several successful series were published.4–10 Many neurosurgeons practicing skull-base surgery (including this author) were carried away by the possibility of total excision with a very low mortality rate and a great postoperative scan, and accepted the accompanying morbidity as inevitable. Only a few wise men dared to question this approach lest they be frowned upon as incompetent.11 But the seeds of doubt were sown and led to soul-searching and rethinking at first by a few and then by the majority. Reports of the successful control of meningiomas through gamma knife radiosurgery further dampened enthusiasm for the high-risk radical surgery of petroclival meningiomas.12 There remains, however, a minority of brilliant neurosurgeons who achieve total excision in the majority of patients with petroclival meningiomas. I am a convert to radiosurgery, not one of the brilliant neurosurgeons who always achieve total excision. In this section of the chapter, I address two principal issues based on personal experience and evidence from the literature. The objective of surgery in patients with a meningioma is total removal of the tumor, including the dural attachment and involved bone. The completeness of surgical removal is the single most important prognostic factor for tumor recurrence. However, when total removal entails unacceptable risks of morbidity or mortality, it is prudent to be satisfied with subtotal excision. Sound judgment in choosing the best treatment depends on a high level of clinical acumen, for the best treatment is that which is best for the patient, not necessarily what is best for the tumor! Another related question to ask is, What constitutes total excision? Total excision, including the dural attachment and bone (Simpson grade I), is not always possible in patients with petroclival meningiomas. By the time patients present to the surgeon, most petroclival meningiomas have reached a large size with a wide attachment, and the tumor often invades the exit foramina of multiple cranial nerves. Total excision of the tumor with its dura and bony attachment is not possible in such cases without significant risks and unacceptable morbidity. In several cases, the difficulty of excision is further compounded by arterial and brainstem involvement.3,13–15 A review of the literature clearly demonstrates the trend toward less aggressive surgery and an emphasis on the functional outcome, as reported in various series (Table 3.1). The total excision rates dropped over the years from a high of 70 to 80% to less than 40%. The total excision rates in the earlier literature reported by Samii and colleagues,5 Al-Mefty and Smith,2 Misra and coworkers,8 Kawase and colleagues,7 and Bricolo and associates,9 were 71%, 83%, 82%, 70%, and 79%, respectively. The total excision rates for petroclival meningiomas in the recent reported series are much lower: 20% by Jung and colleagues,16 40% by Little and associates,14 and 41% by Mathiesen and coworkers.17 The total excision rate in the series of Sekhar and associates6,13 dropped from a high of 78% in 1990 to 32% in 2007. Similarly, the group from Barrow Neurological Institute reported a total excision rate of 91% in 1992 but only 43% in 2007.10,18 The trend toward a less radical approach in almost all recent series is aimed at a better quality of life for the patient. That this attempt is successful is proven by lower post-operative morbidity rates reported in the recent series. I have had a similar experience, operating on 81 patients with petroclival meningiomas, mostly large and giant, between 1988 and 2008. Of the 70 patients treated up to 2006, 58 underwent microsurgery; six of these had adjunct gamma knife radiosurgery, and primary gamma knife radiosurgery was the modality used for 12 patients. A comparison of postoperative function of patients in my series between those operated on before 1997 (radical excision) and those operated on in 1997 or later (safe excision with gamma knife radiosurgery) demonstrated that the morbidity was significantly lower in the latter group (Fig. 3.1). Table 3.1 Petroclival Meningiomas: Rate of Total Excision

Management of Petroclival Meningiomas: Subtotal Resection and Radiosurgery vs. Total Removal

Management of Petroclival Meningiomas: The Role of Excision and Radiosurgery

Total or Subtotal Excision of Petroclival Meningiomas

Authors (Year) | No. of Pts. | Gross Total Resection (%) |

Samii et al (1989)5 | 24 | 71 |

Sekhar et al (1990)6 | 41 | 78 |

Al-Mefty and Smith (1991)2 | 18 | 83 |

Misra et al (1991)8 | 11 | 82 |

Kawase et al (1991)7 | 10 | 70 |

Bricolo et al (1992)9 | 33 | 79 |

Spetzler et al (1992)10 | 46 | 91 |

Jung et al (2000)16 | 49 | 20 |

Little et al (2005)14 | 137 | 40 |

Mathiesen et al (2007)17 | 29 | 41 |

Natarajan et al (2007)13 | 150 | 32 |

Bambakidis et al (2007)18 | 46 | 43 |

What happens, then, to the patients with subtotally excised petroclival meningiomas? One needs to study the natural history of these lesions, both untreated and partially excised, before arriving at any conclusion, but there are conflicting data in the literature. The growth pattern of untreated petroclival meningiomas is unpredictable and variable, with a radiological progression of 58 to 76%.19,20 But radiological progression does not always correlate with clinical worsening. Moreover, the clinical progression, when it did occur, was often mild and not disabling.19 The growth rate of subtotally resected petroclival meningiomas without adjunct treatment seems to be low, and there is a suggestion that recurrence and growth rates are higher if a large residual tumor is left behind and in younger patients.13,14,16 The recurrence rate after complete and incomplete excision was almost the same, 4% and 5%, respectively, in the series of Natarajan and colleagues,13 although a large number of patients with incomplete resection had adjunct radiation. In summary, many committed skull-base surgeons have a significant number of patients with petroclival meningiomas in their series who undergo subtotal excision, resulting in reduced overall postoperative morbidity. The recurrence rate after near-total or subtotal excision is not alarming.

Another equally important question is, What constitutes near-total, subtotal, or partial excision and radical decompression? Although some authors have tried to quantify these terms, there is no consensus about the use of the terminology. One surgeon’s subtotal resection may be near-total for another. Although it is critical to have unambiguous definitions so that meaningful comparisons can be made across groups, unless these definitions are made based on the volume of the residual tumor, a fallacy remains. Dogmatic dictums are not going to work, as each surgeon must discover how far he or she can go without damaging the patient; hence, the concept of safe radical decompression. Each series, then, should be followed up with a mention of residual volume.

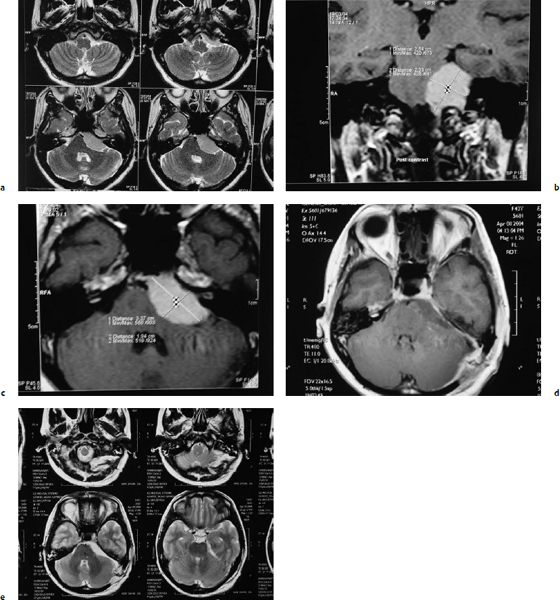

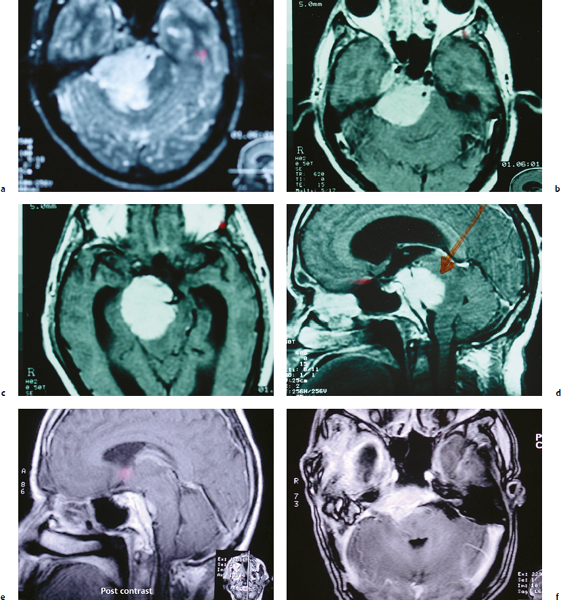

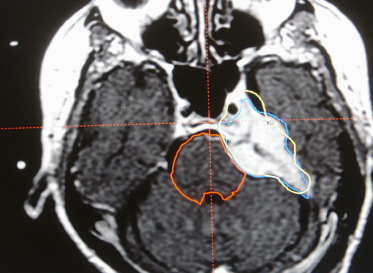

Is there a place for “total” excision of petroclival meningiomas then? Yes. An attempt at total excision can be made in less than 50% of patients. A moderate-sized petroclival meningioma with a good plane of cleavage from the adjacent neurovascular structures and without a wide attachment can be totally excised, as was done in the patient illustrated in Fig. 3.2. A planned subtotal excision is the way to go when the imaging findings suggest an excessive adhesiveness of neurovascular structures, a pial breach, brainstem edema, or a wide en plaque attachment of the tumor involving the exit foramina of multiple cranial nerves (Fig. 3.3). Similarly, the author recommends leaving an intracavernous extension of the tumor (Fig. 3.4). Despite all the recent advances in imaging, surprises during surgery are not uncommon. A seemingly difficult meningioma may occasionally be totally excised, whereas an “easy” tumor may be only subtotally excised, mainly because of excessive adhesiveness and infiltration of neurovascular structures.

The Role of Radiosurgery

Radiosurgery has become an accepted modality of treatment for patients with petroclival meningiomas, both as an adjunct to microsurgery and as a primary modality.13,16,17,21–27 Long-term follow-up data now confirm the tumor control rate of more than 90% reported in earlier series with shorter follow-up. Zachenhofer and associates26 reported a tumor control rate of 94% in patients with skull-base meningiomas treated with gamma knife radiosurgery after a mean follow-up of 103 months. Tumor shrinkage and clinical improvement continued during the longer follow-up period. Kreil and colleagues22 reported long-term follow-up of one of the largest series of benign skull-base meningiomas treated with gamma knife radiosurgery. In a series of 200 patients with a follow-up of 5 to 12 years, 99 were treated with a combination of microsurgery and gamma knife radiosurgery and 101 patients underwent primary gamma knife radiosurgery. The authors reported an actuarial progression-free survival rate of 98.5% at 5 years and 97.2% at 10 years.23 The neurologic status improved in 41.5%, remained unaltered in 54%, and deteriorated in 4.5% of patients, whereas only five patients (2.5%) required repeated microsurgical resection. Iwai and associates,24 reporting the long-term results of low-dose treatment in patients with skull-base meningiomas with gamma knife radiosurgery, reported a slightly lower actuarial progression-free survival rate of 93% at 5 years and 83% at 10 years.

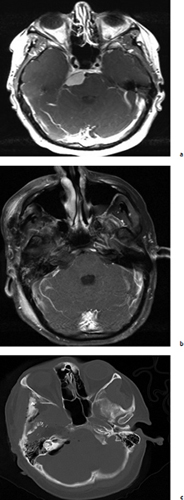

Fig. 3.2a–e Pre- and postoperative magnetic resonance imaging studies from a patient with a petroclival meningioma. (a) Pre-operative T2-weighted image. (b) Preoperative T1-weighted image with coronal contrast. (c) Preoperative T2-weighted axial image with contrast. (d) Postoperative T1-weighted axial image with contrast. (e) Postoperative T2-weighted axial image showing total excision. The patient had no neurologic deficits after surgery.

Some cynics ascribe the control rate of skull-base meningiomas after radiosurgery to a mere function of the natural history and low growth rate of many skull-base meningiomas. Yet the same surgeons do not hesitate to advocate early surgery for small skull-base meningiomas for better functional outcome. If a pathological entity has a 10-year progression-free survival rate of more than 95% as its natural history, it definitely needs no treatment! It is true that many petroclival meningiomas grow slowly and may remain static for long periods. I believe it is prudent to offer a period of observation to asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patients with petroclival meningiomas, especially elderly ones, and do neither microsurgery nor radiosurgery. However, a symptomatic patient with a large petroclival meningioma who has had a subtotal excision presents a completely different situation and is better treated up front with radiosurgery for the residual tumor.17 These patients were symptomatic enough to need surgery in the first place, and second, very importantly, poor follow-up in many referral centers led to patients again presenting with a large recurrence requiring a repeated microsurgery. For a minimal residual tumor after surgery and in elderly patients, a watchful-waiting policy rather than up-front radiosurgery is an equally acceptable option. Similarly, a patient who has had a petroclival meningioma for many years before requiring surgery, reflecting a slow growth rate, can be followed with a scan-and-watch policy after subtotal excision.

What about primary radiosurgery for petroclival meningiomas? I am not a great fan of this approach because there is the possibility of a wrong diagnosis and the inability to grade the meningioma. However, I do advise primary gamma knife radiosurgery in selected patients with a classic imaging morphology, especially in elderly or medically infirm patients with progressive cranial nerve deficits and a small-volume tumor based on the bone and dura or presenting en plaque (Fig. 3.5).

What are the risks of radiosurgery? The two main concerns are neurologic worsening and the risk of malignancy. Radiation-induced worsening is often delayed, requires active medication, and, hence, requires long-term follow-up. Tissue tolerance to radiosurgery is often dose dependent, and recent series show that lower dose treatment has reduced the complication rates significantly.17,22,25,28 There still remains a finite, though small, percentage of patients who develop neurologic deficits ascribable to radiosurgery. These instances range from 0 to 6% and occur mainly in the form of cranial nerve deficits.22–26 Thus, it is critical that the tumor volume is reduced through safe microsurgery, the brainstem is decompressed, and any small residual volume is treated with radiosurgery to achieve the optimal outcome.17,21

The other concern is that of malignancy after radiosurgery, but there is no evidence of this phenomenon other than what is seen in the general population.25,29

Conclusion

Not all patients with petroclival meningiomas need microsurgical or radiosurgical treatment. Many who come to the neurosurgeon, however, have advanced disease and need intervention, though not always without a period of observation. In fewer than half the patients, the meningioma can be excised totally without aggravating neurologic deficits. The rest are better managed through subtotal excision. A majority of patients who have had a subtotal excision are better treated through up-front adjunct radiosurgery (especially if they were operated on for a large symptomatic tumor). Some petroclival meningiomas may never need intervention, and a select group of patients with petroclival meningiomas is better treated with primary gamma knife radiosurgery. A flexible approach of individualizing the treatment protocol for a given patient goes a long way toward satisfying the patient and freeing the surgeon from guilt. I think I would be comfortable with this paradigm if I were the patient!

Total Removal of Petroclival Meningiomas

Case

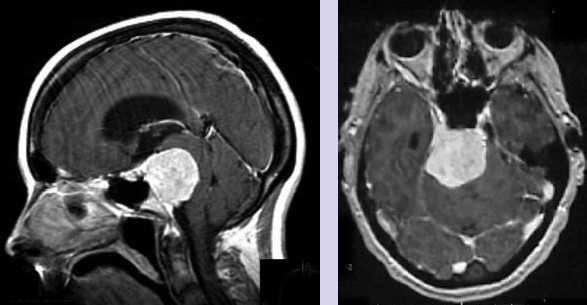

The contrast-enhanced axial and sagittal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of this patient show what appears to be a petroclival meningioma. There is typical displacement of the brainstem in the contralateral and posterior direction and posterior and contralateral displacement of the brainstem. There is also an extension into the posterior cavernous sinus. This patient’s ventricular system above the aqueduct appears enlarged on the sagittal view, and her right temporal horn is prominent. Her diplopia is likely from compression of the abducens nerve and her trigeminal neuralgia from lateral displacement of the fifth nerve, characteristics consistent with the known growth pattern of these tumors. Clinically, the status of the patient’s hearing in the ipsilateral ear is unknown, as is her handedness as a surrogate for hemispheric dominance. Radiographically, the patient’s venous architecture, an important consideration for selecting the approach, cannot be ascertained from these images, and the basilar artery is difficult to discern. Moreover, the tumor’s calcification and water content, features that help the physician infer the tumor’s consistency, are difficult to judge from the images provided.

The Case for Surgery

Petroclival meningiomas are rare, accounting for less than 0.5% of intracranial tumors30 and their surgical anatomy is also complex. They arise at the petroclival junction, medial to the trigeminal nerve, and compress the brainstem and the basilar artery and its perforators to the contralateral side. They displace the middle cranial nerves and often span the middle and posterior fossae, occasionally extending into the cavernous sinus. Consequently, the surgeon’s management of these technically challenging lesions is usually refined over time.

The first decision is whether or not to treat this likely menopausal patient, whose tumor growth may be slowed. Although mild diplopia and medically responsive facial pain are fairly benign and may be managed nonsurgically, a further clinical decline is inevitable; worsening cranial neuropathies, symptoms of brainstem compression, and manifestations of hydrocephalus will ensue. The patient is young and treatment of the tumor is most certainly indicated.

The tumor is too large for radiation therapy alone and as yet there are no meaningful chemotherapeutic treatments. Contemporary treatment options are radical surgical resection, or a more conservative decompression or debulking followed by radiation therapy to the residual tumor. Although early reports have shown the feasibility of surgically resecting these formidable tumors,4,31 an emerging body of literature has endorsed more conservative surgical approaches coupled with radiotherapy to preserve the patient’s quality of life. The strategy of using subtotal resection and radiosurgery rests upon the assumption that the immediate surgical risk and likelihood of cranial neuropathies are reduced and that radiosurgery is an equal surrogate for surgery in the long-term management of intentionally unresected tumors. Although some reports are sanguine about the results,13,14,16,18,32–34 this approach ultimately fails to recognize the serious issue of the long-term failure to control the tumor after radiosurgery and the potentially aggressive growth pattern of recurrent or residual tumors.35 The detection of a recurrence as late as 14 years after the initial radiation treatment highlights the need for extended long-term follow-up in these patients.35

Anecdotally, we are seeing a surge in recurrent tumors in patients from various centers around the world who were treated initially through planned subtotal resection followed by radiation and who may then have undergone additional surgery and radiation. In these patients, the surgical landscape is so treacherous, with scar tissue from previous surgery and radiation vasculopathy, that the chance of cure is essentially lost. Other centers may also be able to attest to the difficulty of managing tumor growth after subtotal surgery and radiation. A residual meningioma may remain stable for some time,36 but some reports suggest that radiation therapy for a residual meningioma offers inadequate long-term control, with a recurrence rate of up to 75% in one series.37

For this patient, we favor surgery with complete resection as the therapeutic goal, in accordance with Simpson’s ageless mandate that the likelihood of a meningioma recurrence is directly related to the extent of surgical resection.38

Surgery

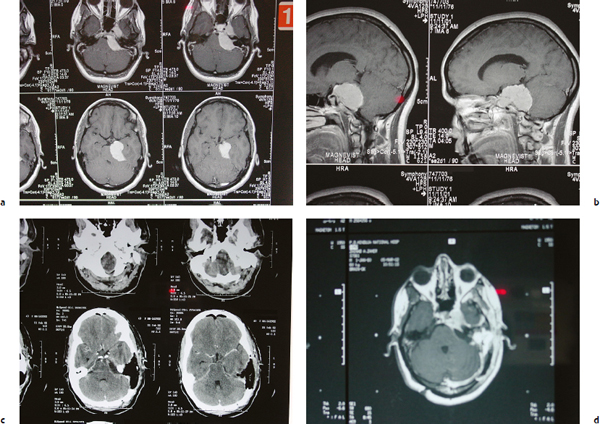

Multiple surgical approaches have been promoted to attack these formidable lesions. Essential to the safe and successful removal of these tumors in the petroclival region is the ability to visualize the tumor and the critical adjacent neural and vascular structures, direct access to which is obscured by the petrous temporal bone. General unfamiliarity with this bony anatomy among neurosurgeons has led to the use of the more traditional suboccipital and pterional approaches to petroclival tumors.18,39,40 However, lateral skull-base approaches through the petrous bone have among their advantages a decreased operative distance to the tumor and neurovascular structures, improved visualization and illumination, and decreased brain retraction.41 In addition, the access for dissection is improved because of the lateral and anterior projection to the brainstem. Specific approaches through the petrous bone include removing the petrous apex in the middle fossa approach, resecting the presigmoid retrolabyrinthine petrous bone in the posterior petrosal approach,4,31 and complete petrosectomy.

Fig. 3.6a–c A petroclival meningioma of the upper clivus. Use of the anterior petrosal approach facilitated its safe and total removal. (a) Preoperative MRI. (b) Postoperative MRI. (c) Postoperative computed tomography scan showing the bone removal.