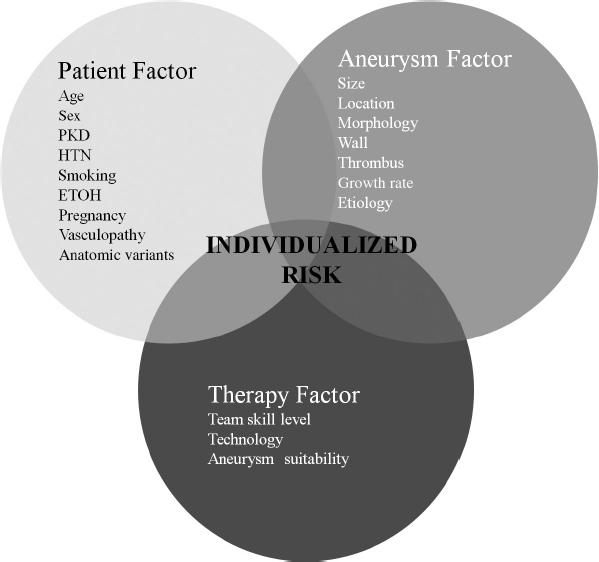

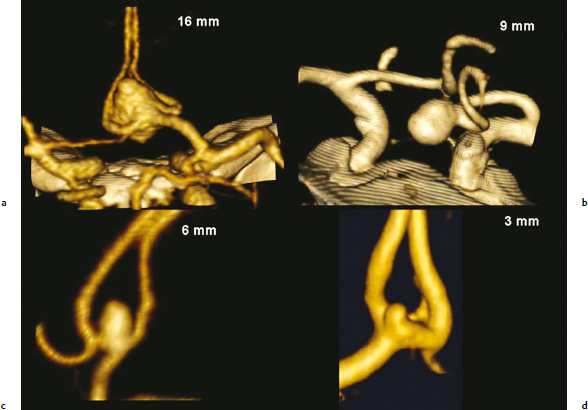

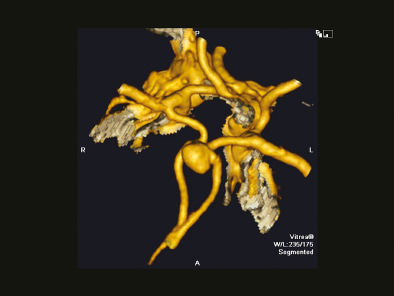

Chapter 13 Case A 40-year-old woman with no family history of intracranial aneurysms presents with an incidental 7-mm anterior communicating artery (ACoA) aneurysm. She has never smoked cigarettes. The treatment of this and other patients with incidental unruptured aneurysms is largely dependent on the natural history. This chapter discusses the controversies and the most current views on the natural history of intracranial aneurysms. Participants Endovascular Treatment of Unruptured Aneurysms: Aditya Bharatha, Timo Krings, and Karel terBrugge Surgical Clipping of Unruptured Anterior Communicating Artery Aneurysms: Ali F. Krisht Management of Unruptured Anterior Communicating Aneurysms: Natural History: Ning Lin and Rose Du Moderator: Management of Unruptured Anterior Communicating Aneurysms: Coiling vs. Clipping vs. the Natural History: Robert F. Spetzler The optimal treatment of patients with an asymptomatic saccular unruptured intracranial aneurysm (UIA) remains controversial. The most significant complication is rupture and subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) with its attendant morbidity and mortality. Hence, the goal of therapy is to identify those patients in whom the risks posed by the aneurysm itself outweigh the risks of possible treatment options and, where treatment is indicated, to identify the optimal strategy among the choices available. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms are not rare. Based on autopsy and angiographic series, estimates of their prevalence have ranged greatly—from less than 1% to more than 10% depending on the patient population and study methodology. As expected, retrospective autopsy series have yielded the lowest apparent prevalence, whereas prospective angiographic series show the highest. A large systematic review of available series estimates their prevalence in the general population at around 2%.1 Aneurysms are more common in women, patients with polycystic kidney disease, older patients, and those with a first-degree relative with an aneurysm or SAH. Other risk factors consistently associated with aneurysm formation are cigarette smoking, hypertension, and excessive alcohol use.2 When considering whether to treat a patient with a UIA, a crucial piece of information is the natural history of the lesion, specifically the likelihood of rupture. The International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms (ISUIA) investigators have published the largest retrospective and prospective studies of the natural history of UIAs: ISUIA-I, with 1,449 patients and > 12,000 patient-years of follow-up,3 and ISUIA-II, with 1,692 patients and > 6,500 patient-years of follow-up,4 respectively. Based on a mean follow-up of 8.3 years, the annual rate of rupture in patients in ISUIA-I was 0.3%, 1%, and 0.05% for aneurysms greater than, equal to, or less than 1 cm, respectively. Aneurysms in the posterior circulation and posterior communicating artery were associated with higher risk. In the group of patients who received conservative treatment in the prospective ISUIA-II, the mean rate of SAH per patient-year was 0.8% over a mean follow-up of 4.1 years. The cumulative 5-year risk of bleeding for anterior circulation aneurysms was 0% for aneurysms smaller than 7 mm (1.5% in those with previous fully treated aneurysmal SAH), 2.6% for aneurysms 7 to 12 mm, and 14.5 to 40% for larger aneurysms. For posterior circulation and posterior communicating artery aneurysms, the 5-year rupture rates ranged from 2.5% for aneurysms smaller than 7 mm to 50% for giant aneurysms. These data have supported a more conservative approach to small anterior circulation aneurysms in recent years, with the caveat that a 0% rate of rupture of aneurysms smaller than 7 mm in ISUIA-II is implausibly low given that, in clinical series of ruptured aneurysms, these make up 35 to 50%,5 pointing to possible selection bias. Wermer and colleagues6 have published a meta-analysis of 19 studies (including the ISUIA data) published between 1966 and 2005, with a total of 6,556 UIAs in 4,705 patients and a mean follow-up of 5.6 years. The overall risk of rupture per patient-year at risk was 1.2% in studies with a mean follow-up of less than 5 years, 0.6% in studies with a mean follow-up between 5 and 10 years, and 1.3% in studies with a greater than 10-year follow-up. Factors associated with greater risk were a size greater than 5 mm, symptomatic presentation, posterior circulation location, female sex, age greater than 60 years, and Japanese or Finnish descent. Smoking was also associated with greater risk, although this risk was not statistically significant. Undoubtedly, other factors also influence the rate of rupture. Likely candidates include patient-specific factors such as background vasculopathy, hypertension, alcohol use and family history, and aneurysm-specific factors such as morphology (lobulation, daughter sac, aspect ratio7), hemodynamics, aneurysm growth rate, and multiplicity. The presence of mural thrombus and calcification also likely affects the rupture risk. Although the data supporting these variables remain inconclusive, they must be kept in mind in the clinical decision-making process.8 Next, we must consider the treatment risks and benefits. A systematic review of the literature describing coil embolization of UIAs published between 1990 and 2002 (1,379 patients in 29 studies) indicated an overall procedure- related permanent morbidity and mortality rate of 7% and 0.6%, respectively, with a reduced morbidity rate of 4.5% in later studies.9 A large, retrospective, single-institution case series of all 173 UIA patients treated with endovascular means over a 12-year period from 1992 to 2004 indicated a procedure-related mortality rate of 0.5% and permanent morbidity rate of 2.5% (1% severe deficit).10 In a consecutive series of 146 unruptured aneurysms treated with Guglielmi detachable coils (GDCs), Holmin and colleagues11 report a mortality of 0% and permanent morbidity in 3.4%. Although these figures compare favorably to surgical series, no randomized clinical trial has directly compared the morbidity and mortality of endovascular versus surgical treatment in patients with UIAs. The International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) concluded that, in 2,143 patients with ruptured aneurysms in which surgical and endovascular treatment were judged to be in clinical equipoise, the rate of death or dependence at 1 year was significantly less in the endovascular group (24% versus 31%) with a lower cumulative mortality over 7 years.12 In ISUIA-II, the morbidity rates for surgical and endovascular therapy were prospectively compared in a nonrandomized group of patients, 1,917 of whom underwent surgery and 451 of whom had endovascular repair.4 The risk of death or disability at 1 year was significantly less in the endovascular cohort than in the surgical group (12.6% and 9.8%, respectively; 10.1% and 7.1% in the group with previously treated aneurysmal SAH). Overall, the patients in the endovascular group were older and had larger aneurysms and a greater proportion of basilar and cavernous aneurysms. These results suggest that, when both treatments are feasible, the up-front risk from endovascular procedures is lower than that from surgery. But what about efficacy? Considerations of treatment efficacy are limited by relatively small numbers of patients, the length of follow-up, and the mixing of ruptured and unruptured aneurysm data. It has been accepted that satisfactorily clipped aneurysms are effectively cured, and surgical series have indeed shown a very low re-rupture rate in follow-ups of patients with clipped aneurysms that have been completely excluded as shown by angiography. In one series of clipped ruptured aneurysms followed for a mean of 10 years, annual rates of 0.14% for recurrent SAH and 0.09% for asymptomatic regrowth were seen.13 There has been concern regarding the long-term durability of endovascular treatment. Published rates of residual or remnant aneurysm after endovascular treatment have been in the range of 5 to 20%, recanalization rates in the range of 15 to 35%, and retreatment rates of up to 13%. A lower degree of aneurysm occlusion and recanalization are thought to be risk factors for re-rupture, although the data have been conflicting.14,15 Despite these findings, the rates of rebleeding have been low. In a retrospective analysis of 173 patients with coiled unruptured aneurysms treated at a single institution between 1992 and 2004 for a mean of 3.7 years, three aneurysms ruptured (0.5% annual rupture rate), and all of these were giant posterior circulation aneurysms.10 In the series by Holmin and colleagues,11 the retreatment rate was 12% and rebleeding occurred in only one patient (0.68% of coiled UIAs) at a median follow-up of nearly 5 years. The Cerebral Aneurysm Rerupture After Treatment (CARAT) investigators identified all aneurysmal SAH patients treated at their institutions between 1996 and 1998 and reviewed the results in 1,010 patients treated with either surgery (711) or coils (299) who were followed for a mean of 4.4 years.16 The annual rates of retreatment were 13.3% for coiling and 2.6% for clipping in the first year, 4.5% and 0%, respectively, in the second year, and 1.1% and 0% thereafter. Although late retreatment was more common in the coil group, no late retreatment led to death or disability. Rates of rebleeding were low for both groups but were slightly lower in the surgical cohort; annual rates of re-rupture for coiling and surgery were 4.9% and 2%, respectively, in the first year and 0.11% and 0% in subsequent years. Combining these data with the re-rupture rates in the ISAT study shows that the early benefit of coiling would only be reversed after 70 years of follow-up. If we project this data onto the disability and death data from the ISUIA study, it appears that the impact of retreatment would not outweigh the early benefit of coiling even after 100 years of follow-up. Thus, the rate of aneurysm rupture after treatment and the need for repeated treatment is somewhat greater for endovascular therapy, but the difference appears to be small in comparison with the lower rates of procedure-related morbidity. From a health care system perspective, another question is whether the treatment of unruptured aneurysms is cost-effective in terms of its ability to reduce the costs of hospitalization and long-term care. An analysis using Dutch data showed that, for 50-year-old patients, treatment using both surgical and endovascular techniques was cost-effective for a wide range of rupture rate scenarios above 0.3% per year, and slightly more so in women.17 Finally, in applying this disparate information to specific clinical scenarios, it is important to consider the data from the literature in the context of patient-specific, aneurysm-specific, and treatment-specific factors to provide individualized recommendations regarding treatment (Fig. 13.1). Patient-specific factors relating to life expectancy are crucial parameters in determining the appropriateness of UIA treatment. In patients of advanced age or with significant comorbidities, the reduced life expectancy of the patient may result in the up-front risk of treatment exceeding the potential beneficial reduction in risk of SAH. Nonmodifiable risk factors for rupture, such as female sex and etio-logic factors, and modifiable risk factors that may increase the risk of rupture, such as smoking, alcohol use, and hypertension, should also be taken into account. Idiosyncratic factors, such as excessive or debilitating anxiety pertaining to a small unruptured aneurysm, may result in the need to consider treatment for patients who might otherwise be followed. Patient factors can also influence the choice of therapy. Excessive tortuosity of the extracranial vessels can render endovascular treatment difficult or impossible, favoring surgery in some cases. Some patients may reject the idea of follow-up and the possibility of recurrence that goes with endovascular treatment. On the other hand, significant comorbidity may render a patient unable to tolerate the stresses of conventional surgery, making endovascular treatment more attractive. Next, aneurysm-specific factors must be integrated. As discussed above, size plays an important but by no means exclusive role. In addition to influencing predictions about the risk of rupture, aneurysm size can influence the patient’s choice of therapy. Coiling of very small aneurysms (< 2–3 mm) has been associated with an increased risk of rupture, whereas coiling of giant aneurysms has been associated with coil compaction and recanalization. Morphological factors can influence whether coiling is possible and whether assistive techniques such as balloon remodeling or stent-assisted techniques are required. Important parameters that can predict immediate post-coiling occlusion rates include the absolute size of the neck, the dome-to-neck ratio, the aneurysm’s shape, and the incorporation of branch vessels.18 The aneurysm’s location is another important factor. The general rule of thumb is that basilar termination aneurysms, which are difficult to access through surgery, are often more suited for endovascular treatment. Aneurysms of the middle cerebral artery bifurcation often have an unfavorable geometry of branch vessels and are surgically accessible; hence, they are often (but not always) better suited to clipping. For aneurysms in other locations, both treatments are often possible. For example, for distal or peripheral aneurysms, both clipping and endovascular vessel sacrifice are possibilities. For anterior and posterior communicating artery aneurysms, both treatments can often be considered. In many cases, clinical, morphological, and local endovascular or surgical experience are the deciding factors. In other words, factors related to the patient and the aneurysm need to be considered in the context of the technology available and institutional expertise (therapy factors). With the advent of new technologies, the repertoire of both surgical and endovascular therapies will continue to expand. Examples include the recent advances in flow-diverting stents and cerebrovascular bypass procedures. With regard to the clinical case presented with this chapter, a presumably healthy 40-year-old woman with a greater than 30-year life expectancy and an anterior circulation aneurysm 7 mm in diameter, we would expect the cumulative risk of rupture to exceed 15 to 30%, which is much greater than the risk posed by endovascular or surgical treatment. In this location, both surgery and coiling are feasible, but we would want to offer the most effective treatment with the lowest risk. For patients in whom both options are equally feasible, we would advocate coiling given the lower up-front risks. However, in this case, based on the image provided, incorporating the A2s into the neck may increase the risks of coiling both in terms of thromboembolic complications and residual aneurysm, and this aneurysm is also quite suitable for surgery. Therefore, this case ultimately highlights how important it is that decisions regarding the choice of treatment be made in a systematic manner, based on careful analysis of the patient, the aneurysm, and all of the available therapeutic options. In the past, a patient diagnosed with a UIA was considered to be a person walking around with a ticking time bomb in his or her head. Recent reports and studies, however, suggest that the natural history of unruptured aneurysms may be more benign than what was previously thought.3,4,19–21 This is especially so when dealing with small aneurysms. Investigators from the ISUIA suggested that aneurysms arising from the posterior communicating artery or the basilar tip region are more prone to bleed than aneurysms arising from other locations in the anterior circulation.3,4 This assessment included aneurysms involving the ACoA complex. But as most neurosurgeons dealing with ruptured aneurysms on a routine basis know, lesions of the ACoA account for a large percentage of patients arriving in the emergency room with a ruptured aneurysm.1,22–25 In addition, the ISUIA study included a relatively smaller number of ACoA aneurysms when compared with most surgical series. This may very well suggest that the majority of ACoA aneurysms present with rupture and a smaller number present in a nonruptured state (Fig. 13.2). Most neurosurgeons who regularly treat patients with aneurysms have a problem with such conclusions, in part because the ISUIA has predominantly focused on size in drawing its conclusions. Although the size of the unruptured aneurysm is a factor to be considered in the decision-making process, it should not always be considered the primary factor. The majority of lesions in several reported series of ruptured aneurysms were small. In addition, there is a long list of factors that may play a role in the etiology of aneurysmal rupture7,26–55 (Table 13.1). For most of these factors, the extent of their influence on the rupture rate is not known. Defining how these various factors influence the activity within an aneurysm may one day help us differentiate between active and inactive aneurysms. With regard to ACoA aneurysms, several studies reached conclusions contrary to those of the ISUIA. In a meta-analysis of natural history studies, Mira and colleagues56 found that the risk of rupture for unruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysms was twice that of other locations (95% confidence interval, 1.29–3.12). Furthermore, in a study from Japan involving 13 hospitals, Yonekura57 reviewed the rupture rates of aneurysms less than 5 mm in size. This study included 329 patients with 380 aneurysms and a mean follow-up of 13.8 months. The author found that the annual rupture rate was 0.8%, but 18 of the aneurysms had enlarged (seven grew more than 20 mm) during the study period and were treated because of concern about their growth and the possibility of rupture. This approach obviously created a bias in the final annual rupture rate, which means the figure of 0.8% is probably an underestimate of the real rupture rate if those 18 aneurysms had been left untreated. The author also found that the risk of enlargement and rupture was influenced by the location at the ACoA complex in addition to other factors. To recommend treatment for any patient with an unruptured aneurysm, it is clear that the proposed treatment must have a much higher chance for a better outcome than the natural history. For this reason, when we evaluate a patient with a small aneurysm of the ACoA, we take into consideration the following factors for the following reasons: Table 13.1 Factors that May Influence Aneurysm Rupture

Management of Unruptured Anterior Communicating Aneurysms: Coiling vs. Clipping vs. the Natural History

Endovascular Treatment of Unruptured Aneurysms

Surgical Clipping of Unruptured Anterior Communicating Artery Aneurysms

The hemodynamics, shape, and growth rate of the aneurysm Multiple aneurysms The regional perfusion pressure The volume–pressure relationship Wall thickness The relationship of the aneurysm to the parent vessel The genetic makeup of the vessel wall The patient’s ability to repair The patient’s use of tobacco, alcohol, or both Elevated blood pressure |

Patients who are younger have a longer life expectancy and a higher cumulative risk of rupture during their lifetime. According to findings in studies by Juvela and colleagues40–42,58,59 in Helsinki, the 30-year rupture rate of aneurysms in general was 30.3%. Therefore, patients who are in their 40s have a greater than 30% chance of rupture during their lifetime. In other words, they have up to a 15% chance of dying or being severely disabled. This risk should be an indication for initiating treatment. Whether the treatment should be through microsurgical clipping or endovascular means is the subject of the moderator’s comments at the end of this chapter.

Other factors that have previously been noted to influence the rate of rupture include a history of heavy cigarette smoking, a family history of aneurysms, and untreated or uncontrolled hypertension. More recently, several studies suggested that the morphological features of the aneurysm, especially those related to size, may correlate with aneurysmal rupture.60

One of the most important factors yet to be evaluated for its influence on the rupture rate is the quality of the wall of the aneurysm. Until now, we have had no way to evaluate or assess this quality. In a pilot study at our institution, we reviewed the occurrence of a “blistering” type of change in 100 patients with UIAs treated through microsurgical clipping. In 90% of the cases examined, there was a significant weak spot in the aneurysmal wall that might later be the location for a potential rupture. This observation emphasizes our lack of knowledge about which aneurysms will bleed and which will not.

Because of the complexity of the facts described here, it continues to be very difficult for the treating neurosurgeon to decide whether a small UIA should be treated or left alone. Therefore, to help surgeons make a more educated decision, we evaluated our experience with surgical clipping of unruptured aneurysms as it compares with a 10-year survival for patients with unclipped aneurysms.61 This study was conducted in 116 consecutive patients with 148 aneurysms. These aneurysms were divided into the four groups defined by the ISUIA: small, medium, large, and giant aneurysms. We then statistically analyzed the severe morbidity and mortality expected to occur if our cohort of patients had been included in the ISUIA and were not operated on. These results were compared with the surgical outcomes in our patients. The analysis showed a statistically significant difference in the morbidity rate, but surgical intervention had a positive and significant impact on the mortality rate.

In conclusion, contrary to the ISUIA results, ACoA aneurysms are more common clinically and have a higher rate of rupture than what was reported in unruptured aneurysm studies. For this reason we should have a low threshold for treating them, especially in younger patients. We strongly advocate microsurgical clipping because nowadays, and in experienced hands, it has a very low rate of morbidity and mortality and it is superior to coiling in its durability and in providing patients with peace of mind, especially in terms of the future need for retreatment or the possibility of bleeding.

Management of Unruptured Anterior Communicating Aneurysms: Natural History

The prevalence of cerebral aneurysms is estimated to be 1 to 2% in the general population1,62,63 and could be higher in the elderly.64 The management of an incidentally discovered intracranial aneurysm remains one of the most controversial topics in neurosurgery. Therapeutic options such as microsurgical clipping or endovascular coiling are offered to eradicate the potential risk of aneurysm rupture, which results in SAH and can lead to devastating morbidity and mortality. These interventions, however, also carry certain risks, and in some situations may do more harm than good. Therefore, it is essential to understand the natural history of UIAs and carefully balance the risks and benefits of all treatment options offered to a patient.

Observational Study and Meta-Analysis

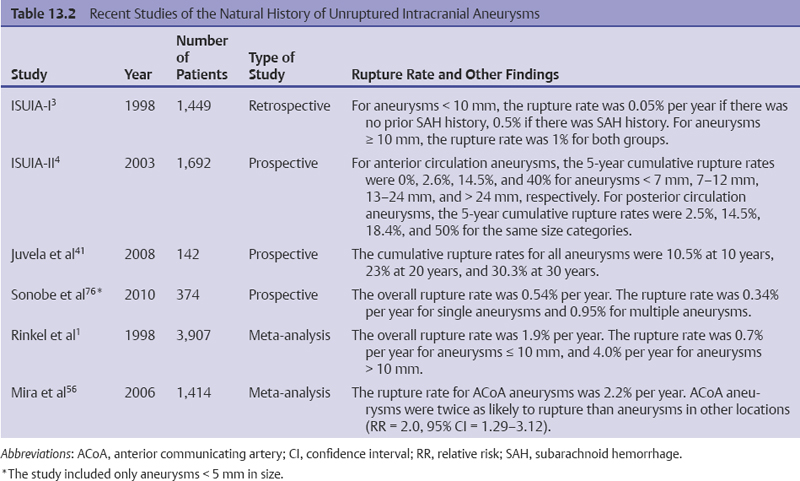

The natural history of a UIA can ideally be assessed by a prospective, randomized trial. Nevertheless, given the severe consequence of SAH and the generally low incidence of aneurysmal rupture, clinicians and surgeons have been reluctant to perform such a study.65 Instead, several observational cohort trials and meta-analyses have been conducted and published in the last decade; these represent our best knowledge in estimating the bleeding risk of UIAs (Table 13.2).

The most widely cited reports are probably the two seminal papers by the ISUIA investigators.3,4 The first study, ISUIA-I, consisted of a retrospective analysis of 1,449 patients harboring 1,937 unruptured aneurysms for a follow-up duration of 8.3 years.3 These patients were purposefully divided into two groups: group 1 contained 727 patients with no history of aneurysmal SAH, and group 2 contained 722 patients who had previous aneurysmal SAH but recovered well (Rankin scale 1–2). In group 1, the annual rupture rate was 0.05% for aneurysms smaller than 10 mm and 1% for aneurysms equal to or larger than 10 mm. In group 2, the annual rupture rate was 0.5% for smaller aneurysms and 1% for larger aneurysms. These results were drastically lower than the majority of those from previous, smaller-scale observational studies.26,59,66–68 After the study, many questions were raised regarding selection bias, censoring during the follow-up period, and the composition of aneurysms in different locations.19,64,69,70 Consequently, there was a strong demand for a larger, better designed study to further address the natural history of UIAs.

The second study (ISUIA-II) from the same group of investigators was published in 2003 and consisted of a prospective analysis of 1,692 patients with 2,686 aneurysms for a follow-up period of 4.1 years.4 The patients were again divided into two groups based on SAH history, and the bleeding risk was stratified according to the location and size of the aneurysm. For patients with no SAH history (group 1, n = 1,077), the 5-year cumulative rupture rate for anterior circulation aneurysms (excluding cavernous aneurysms of the internal carotid artery) smaller than 7 mm was essentially 0%, and for posterior circulation aneurysms (including posterior communicating artery aneurysms) smaller than 7 mm, the cumulative rupture rate was 2.5%. For patients with a history of SAH (group 2, n = 615), the 5-year cumulative rupture rates for small anterior and posterior circulation aneurysms were 1.5% and 3.4%, respectively. In addition, the cumulative rupture rates were 2.6%, 14.5%, and 40%, respectively, for anterior circulation aneurysms measuring 7 to 12 mm, 13 to 24 mm, and ≥ 25 mm, and were 14.5%, 18.4%, and 50%, respectively, for posterior circulation aneurysms in the same size categories. These results provided better estimates of the natural history of UIAs compared with the retrospective portion of the study; nevertheless, ISUIA-II was still plagued by significant selection bias and design flaws. Of particular concern was the large number of patients who were initially managed conservatively but received treatment during the follow-up period (534 patients, or 31.6%). Moreover, there was a disproportionately low percentage of ACoA aneurysms in the study population (10.3%), well below what was estimated in the general population. Finally, the percentage of ruptured aneurysms smaller than 7 mm was much less than would be expected based on the ISAT, in which more than 90% of ruptured aneurysms were smaller than 10 mm.12,71 This preponderance of small ruptured aneurysms is corroborated by other studies1,72,73 and is not explained by the proportion of small aneurysms in the ISUIA study. Hence, it is highly likely that the study underestimated the bleeding risk in some groups of UIAs, and caution should be taken when applying these results to evaluate a specific unruptured aneurysm.65,74,75

< div class='tao-gold-member'>