55 Minimally Invasive Lateral Retroperitoneal Trans-Psoas Interbody Fusion (e.g., XLIF, DLIF)

I. Key Points

– Success with this technique relies heavily on1

• Careful patient positioning

• Gentle retroperitoneal dissection

• Meticulous psoas splitting with electromyographic (EMG) monitoring

• Fusion bed preparation with release of contralateral annulus

• Appropriate-size interbody implant placement

II. Indications2

– Axial low back pain caused by

• Degenerative disc disease

• Spinal stenosis (mild to moderate only) with significant back pain component

• Grade 1 to 2 spondylolisthesis

• Adjacent-segment disc degeneration

• Interbody fusion as stand-alone or adjunct in treatment of degenerative scoliosis

– Postdiscectomy space collapse with neuroforaminal stenosis (indirect decompression)

– Total disc replacement

– Thoracolumbar corpectomies

• Burst fractures

• Tumors

• Treatment of deformity with sagittal plane imbalance

III. Technique

– Patient positioning

• The patient is placed on a radiolucent bendable table in true 90 degree lateral decubitus position with the top of the crest just inferior to the table break.

• Usually the left side is up, unless the crest is higher on that side or there has been previous surgery on that side.

• Flex the table to increase the distance between the iliac crest and the ribs. This allows access to the disc space (important at L4-L5 to clear the crest and above L3 to clear the lower ribs).

• Localize the skin incision with lateral fluoroscopy by centering crossed K-wires over the disc’s mid-position. For multilevel approaches, a single longitudinal incision with individual transverse fascial openings for each level is adequate.

– Retroperitoneal access (single skin/fascia incision technique)

• Work perpendicular to the floor while dissecting through the muscle fibers to avoid entry into the peritoneal cavity, which is anteriorly displaced in the lateral position.

• Entry into the retroperitoneal cavity is confirmed by the appearance of bright yellow fat and a loss of resistance by the muscle tissues. Finger dissection is then performed so that the surgeon can feel the psoas muscle deep in the cavity and the transverse processes posteriorly.

– Trans-psoas approach and retractor placement

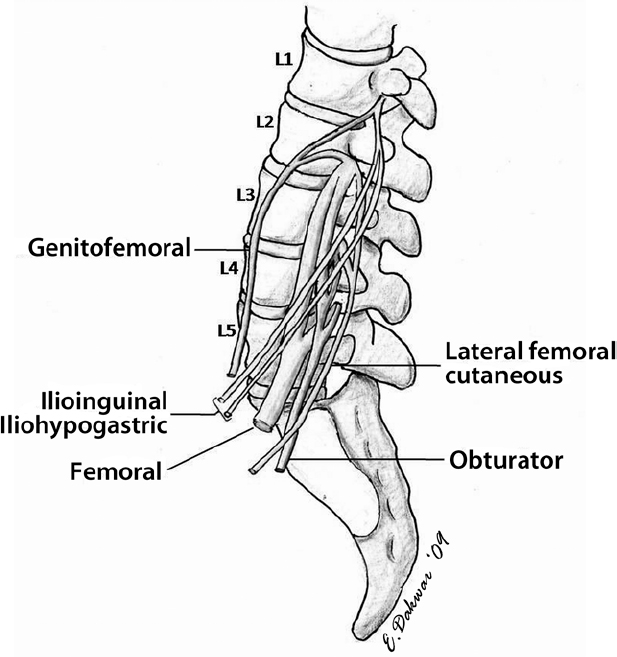

• A series of tubular dilators are placed with EMG monitoring. Directional EMG monitoring (Neurovision, NuVasive, San Diego, CA) allows not only proximity to motor nerves but also the location of these nerves in relation to the dilator (Fig. 55.1). It is essential to guide the dilators with the finger to the psoas muscle to avoid inadvertent entry into the peritoneal cavity.

• Lateral fluoroscopy will guide dilator placement into the middle (or just posterior to the middle) of the disc space while bluntly splitting the fibers of the psoas. A K-wire is placed through the initial dilator and into the disc space to hold it in place. EMG monitoring is performed with each dilator prior to the introduction of a larger dilator.

• The retractor is then placed and a shim needle is introduced to the disc space under AP fluoroscopy to secure it.

– Preparation of the disc space

• The disc space is incised with a knife just anterior to the shim, with a small rim of disc kept just in front of it to keep the retractor from sliding anteriorly.

• A Cobb elevator is passed along both end plates and through the contralateral annulus under fluoroscopic guidance.

• A series of instruments (curettes, pituitaries, rasps) are used to clean the space and prepare the end plates.

– Interbody spacer and instrumentation are then placed.

– The retractor is removed slowly in the open configuration to allow the psoas muscle to be inspected for bleeding.

– The external oblique fascia is closed with interrupted absorbable suture and the skin is closed in a subcuticular fashion.

Fig. 55.1 Lateral view of the lumbar plexus. Understanding this anatomy is critical for successful implementation of the lateral transpsoas approach. (From Uribe JS et al. Defining the safe working zones using the minimally invasive lateral retroperitoneal transpsoas approach: an anatomical study, Journal of Neurosurgery Spine, Aug 2010. Reprinted with permission.)

– Hip flexor weakness, thigh numbness, quadriceps weakness, genitofemoral neuralgia

– Abdominal viscera perforation

– Rupture of anterior longitudinal ligament

– Great vessel injury

– Kidney-ureteral injury

– Graft subsidence

– Psoas/retroperitoneal hematoma

– Abdominal wall paresis

– Rhabdomyolysis

V. Postoperative Care

– For single-level lumbar cases the patient is mobilized in the immediate post-op period without a brace. No drains are placed.

– The patient is usually discharged on postoperative day 1 for single-level cases.

– In case of significant leg weakness or a drop in hematocrit, a computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan is indicated to rule out a psoas hematoma.

VI. Outcomes

– If thigh numbness (12 to 75%) occurs (from retraction against the femoral nerve—anterior femoral cutaneous), it usually resolves by the time of the 3-month follow-up without treatment. This is more common at L4-L5 level due to the proximity of the femoral nerve to the surgical field.1

– Hip flexor weakness correlates with trauma to the psoas muscle. It is rarely a neurogenic injury. Gentle placement of the dilators and retractor limits the incidence of this.

– Quadriceps weakness is likely due to injury of the femoral nerve.

– Arthrodesis rates and clinical outcomes are similar to those for other interbody techniques1–4; however, since the technique is in its infancy, long-term outcomes are still uncertain.

VII. Surgical Pearls

– Do not proceed with surgery unless perfect AP and lateral projections of the disc space have been prepared. This is best accomplished by careful patient positioning, not by adjusting the fluoroscopy machines.

– Minimize the amount of lateral flexion of the patient and flex the ipsilateral hip during positioning. This may decrease the amount of tension on the lumbar plexus.

– Guide the initial dilator with finger dissection through the retroperitoneal space to prevent visceral injury.

– Ideally no nerves will be encountered during EMG stimulation. In other than ideal situations, place the nerve posterior to the retractor, where it can be safely retracted away from the surgical field without the risk of root avulsion or stretch injury.

Common Clinical Questions

1. Which nerve runs over the psoas muscle and is likely to be affected by a lateral approach at L2-L3?

2. What is the most likely explanation for post-op hip flexor weakness?

3. Retraction against which nerve at the L4-L5 level is responsible for post-op anterior thigh numbness?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree