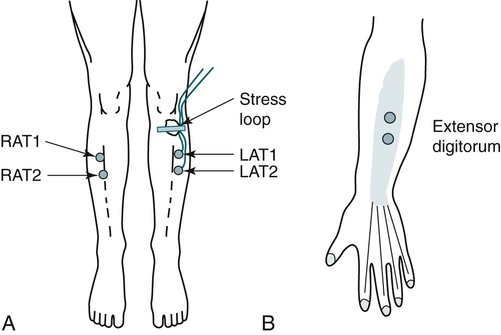

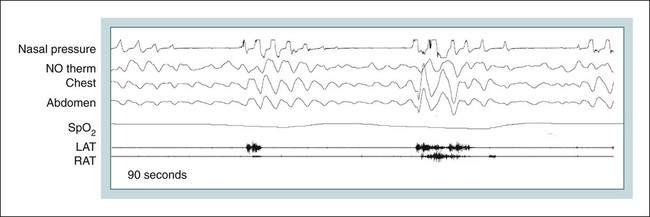

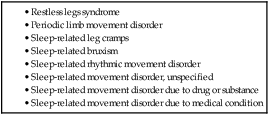

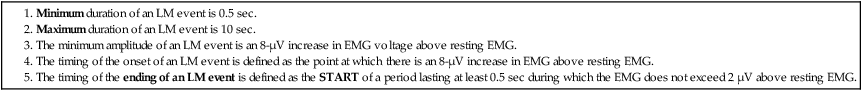

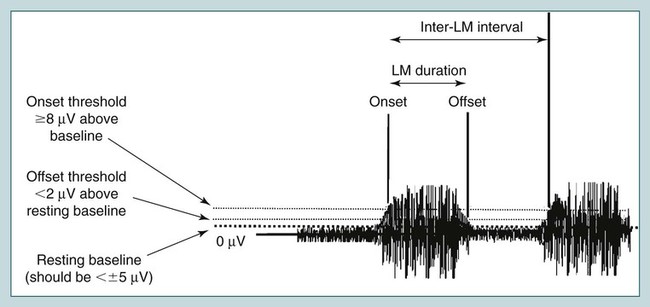

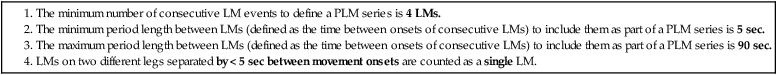

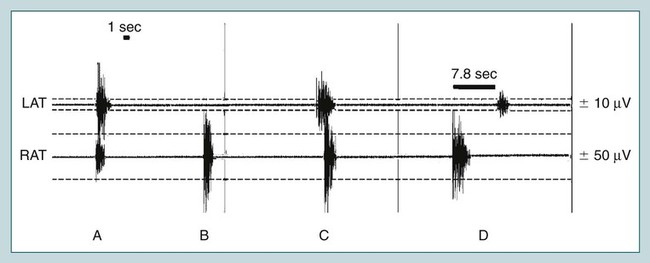

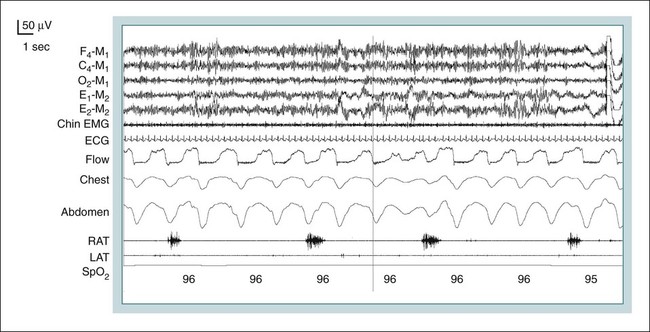

• A significant LM has a duration from 0.5 to 10 seconds and a minimum amplitude 8 µV above the baseline resting EMG. • The minimum number of LMs to define a PLM series (and, hence, LMs are PLMs) is four. The period length between LMs in a PLM series is 5 to 90 seconds (onset to onset). • If the onset of two LMs is separated by < 5 seconds, they are counted as 1 LM. • LMs are not considered part of a PLM series if they occur from 0.5 second before the start of a respiratory event to 0.5 second after the respiratory event. That is, LMs associated with respiratory events are not counted. • PLMD is diagnosed when PLMS is present, RLS is not present, and there is a clinical sleep disturbance or complaint of daytime fatigue, and PLMS and the sleep complaint are not better explained by another disorder. PLMS is common and usually asymptomatic. PLMD is uncommon. • ALMA and HFT occur at a faster rate than PLMs and often occur at sleep-wake transitions. They are felt to have no clinical significance. • The EMG changes associated with the RBD (REM sleep without atonia) can occur in the chin EMG, chin EMG and limb EMG, or limb EMG alone. The changes include a sustained elevation of the chin EMG activity and TMA in either the chin EMG, the limb EMG, or both. • The diagnosis of RBD requires BOTH finding REM without atonia AND either PSG documentation OR a history of dream-enacting behavior. In addition, absence of REM-related epileptiform activity (rare) is required to diagnose the RBD. • Bruxism can occur in any stage of sleep and wake and a rhythmic pattern may be seen in the EEG or chin EMG derivations. The diagnosis of bruxism requires at least two episodes of audible sound of teeth grinding—diagnosis not based on EEG/EMG findings alone. If no sounds are audible, one might simply comment that a pattern typical of bruxism was observed. • The frequency of rhythmic movement disorder movements is 0.5 to 2 Hz. The amplitude of movements must be at least twice the background. Video PSG is extremely helpful in making the diagnosis and documenting the type (e.g., head banging, body rocking). A number of movement disorders are classified in the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 2nd edition (ICSD-2), as sleep-related movement disorders1 (Table 12–1). The restless legs syndrome (RLS) and periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) are discussed in detail in Chapter 23. This chapter discusses monitoring of limb movements (LMs) and also the scoring rules for periodic limb movements in sleep (PLMS), bruxism, the rhythmic movement disorder (RMD), and the rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder (RBD). The chapter also covers three LM patterns considered to be benign conditions: alternating leg movement activity (ALMA), hypnagogic foot tremor (HFT), and excessive fragmentary myoclonus (EFM). These three LM patterns are listed in the ICSD-2 under “Isolated Symptoms and Apparently Normal Variants.” TABLE 12–1 Sleep-Related Movement Disorders (ICSD-2) ICSD-2 = International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 2nd ed. Data from American Academy of Sleep Medicine: ICSD-2 International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 2nd ed. Diagnostic and Coding Manual. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2005. Recording of limb muscle electromyogram (EMG) activity in polysomnography (PSG) is used to document the presence and frequency of LMs.2,3 The EMG activities of the right anterior tibialis (RAT) and left anterior tibialis (LAT) muscles are routinely monitored. However, in patients with suspected RBD, arm muscle EMG activity is also recorded because this disorder is associated with abnormal EMG activity during REM sleep in the arms and legs as well as the chin derivations. The classic periodic leg movement (PLM) consists of extension of the big toe, dorsiflexion at the ankle, and sometimes flexion at the knee and hip—similar to the movement associated with the Babinski reflex. The PSG finding of PLMs is a very common finding and usually not associated with symptoms. However, PLMs can result in sleep disturbance of the patient or bed partner. Leg EMG is recorded using bipolar AC amplifiers with surface electrodes using methods similar to those used to record chin EMG activity. The electrodes should have an impedance less than 10 KΩ (<5 KΩ is preferred). The recommended low- and high-frequency filter display settings are 10 Hz and 100 Hz, respectively. Use of a 60-Hz notch filter is discouraged. Having the patient move the left and right legs (wiggle toes) is part of the biocalibration series. In electroencephalogram (EEG) derivations that use a 35-Hz high-frequency filter, turning off the 60-Hz filter has relatively little effect. However, given the 100-Hz high-frequency filter setting used for leg EMG recording, turning off the 60-Hz filter will significantly increase signal amplitude if 60-Hz contamination is present. This can be minimized by low electrode impedance.2,3 Separate EMG electrodes are placed along the long axis of the belly of the anterior tibialis muscle around the middle of the muscle (Fig. 12–1). The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) scoring manual3 recommends that the electrodes be placed either 2 to 3 cm apart or one third the length of the anterior tibialis muscle, whichever is shorter. As discussed later, because voltage amplitude criteria are used to identify significant LMs, the relaxed leg EMG activity should be less than ± 5 µV. Both legs should be monitored for the presence of LMs. Using a separate channel (tracing) for each leg is strongly preferred. Combining electrodes from the two legs to give a single recorded channel may suffice for some clinical settings, though it should be recognized that this strategy may reduce the number of detected LMs. Movements of the upper limbs may be sampled if clinically indicated. The extensor digitorum is commonly monitored. The muscle is on the lateral/dorsal aspect of the forearm and is an extensor of the digits (see Fig. 12–1). Placement of the electrodes to monitor the extensor digitorum is along the long axis of the belly of the muscle separated by a few centimeters. The location of the muscle can be determined by having the patient extend the arm with the palm down and then make a fist (opening and closing the hand). During biocalibration, the patient is asked to extend the digits to check for signal adequacy. In the following discussion, individual leg (limb) movements are denoted by LM, individual periodic leg movements as PLMs, and the PSG finding of periodic limb movements in sleep by PLMS. Although leg movements (RAT, LAT EMG) are typically monitored, the term periodic limb movements is used to be more inclusive. Scoring criteria for PLMs proposed by Coleman2 were widely used and included in the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 1st edition4 (ICSD-1). Subsequently, a task force of the American Sleep Disorders Association published recommendations for recording and scoring LMs5 using similar scoring criteria and providing many illustrative tracings of LMs. The ICSD-2 used these criteria for defining PLMs.4 Significant LMs were 0.5 to 5 seconds in duration with an amplitude at least one quarter of the LM amplitude during biocalibration.1 Subsequently, the scoring criteria were revised by the World Association of Sleep Medicine (WASM) in collaboration with the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG).6 The major change was extending the maximum duration of LMs to 10 seconds and using voltage amplitude criteria. These criteria for scoring LMs and PLMs are identical with the recommendations of the recently published AASM scoring manual.3,7 Of note, the resting anterior tibialis EMG activity should be less than ± 5 µV. The current criteria for determining a significant LM event are listed in Table 12–2. In the new criteria, a significant LM has a duration from 0.5 to 10 seconds with a minimum amplitude 8 µV above the resting leg EMG. The time of onset is the time at which the amplitude increased to 8 µV above baseline resting activity, and the end of the LM (offset) is defined as the START of a period lasting at least 0.5 second during which the EMG does not exceed 2 µV above resting EMG (Fig. 12–2). Use of voltage criteria based on an absolute increase in microvolts above the resting baseline requires a stable resting EMG for the relaxed anterior tibialis muscle. The absolute signal should be no greater than 10 µV between negative and positive deflections (±5 µV). TABLE 12–2 Rules Defining a Significant Leg Movement Event EMG = electromyogram; LM = leg movement. From Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson A, Quan SF for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine: The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specification, 1st ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2007, pp. 41–42. The AASM scoring manual also provides rules for defining a PLM series (Table 12–3), that is, criteria for identifying a LM as a PLM. The minimum number of consecutive LMs to define a PLM series is 4 consecutive LMs. The time from onset of one LM to the onset of the next LM is 5 to 90 seconds. LMs on different legs separated by less than 5 seconds between LM onsets are counted as a single LM. Figure 12–3 presents a 90-second segment of left and right anterior tibial EMG tracings. TABLE 12–3 Rules Defining a Periodic Leg Movement Series* Note: It is understood that PLMS means that the LMs occur during sleep. LM = leg movement; PLM = periodic leg movement. *Criteria for LMs to be considered PLMs. From Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson A, Quan SF for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine: The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specification, 1st ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2007, pp. 41–42. An LM should not be scored if it occurs during a period from 0.5 second before an apnea or hypopnea to 0.5 second after an apnea or hypopnea (LMs associated with respiratory events are not scored).3 The scoring rules did not provide information about scoring LMs associated with respiratory effort–related arousals (RERAs). However, some clinicians would extend the previous rule to RERAs. It is not uncommon for LMs to be noted at apnea termination even if an associated cortical arousal is not present. In Figure 12–4, the leg EMG bursts associated with respiratory events are not scored as LMs or PLMs. According to the AASM scoring manual, an arousal and PLM should be considered associated with each other (Fig. 12–5) when there is less than 0.5 second between the END of one event and the ONSET of the other event, regardless of which is first. This recommendation differs from previous criteria, which required the arousal to follow the onset of the PLM by not more than 3 seconds. Of note, the term PLMS implies that PLMs occur during sleep. The AASM scoring manual3 recommends reporting the number of PLMS and the periodic limb movement in sleep index (PLMSI), which is the number of PLMs per hour of sleep. The number of PLMs associated with arousal and the periodic limb movement in sleep arousal index (PLMSAI) should also be reported. The AASM scoring manual did not recommend criteria for scoring periodic limb movements during wake (PLMW). The WASM in collaboration with the IRLSSG6 published recommendations for PLMW. The criteria for PLMW events is the same as for PLMS events except that the patient is awake (Fig. 12–6). The PLMW index is defined as the number of PLMW events divided by wake time (hr) from lights out to lights on while the patient is in bed. That is, time when the patient is out of bed or sitting on the side of the bed is not included. Of note, frequent PLMW events are highly suggestive of the RLS. If PLMW events are noted, the patient history should be reviewed to determine if RLS symptoms are reported. The Suggested Immobilization Test (SIT) was developed to help make the diagnosis of the RLS.8 The test detects and counts PLMW. The patient sits with the legs outstretched and attempts to keep the legs still for 30 minutes to an hour. EMG recording of the left and right anterior tibialis muscles is performed. The test is often administered in the evening. The combination of rest and monitoring in the evening worsens RLS. In one study of the SIT, patients with RLS had significantly more PLMW than controls (76.1/hr vs. 26.9/hr). In this study, using a PLMW index of 40/hr to diagnose RLS, the sensitivity and specificity were 81% and 81%, respectively (compared with RLS clinical criteria based on history). PLMS is discussed in more detail in Chapter 23. There are no widely accepted criteria for what constitutes a normal, mildly, moderately, or severely increased PLMSI. In the ICSD-1,4 the following severity scheme was recommended: PLMSI less than 5/hr normal, 5 to 25 mild, 25 to less than 50/hr moderate, and greater than 50/hr severe. A PLMSAI greater than 25/hr was identified as severe. It has been recognized that most patients with PLMS in the absence of the RLS are usually asymptomatic. Approximately 80% to 90% of patients with RLS will have PLMs on a given sleep study.9 The PLMD (clinical sleep disturbance or daytime fatigue due to PLMS without RLS) is thought to be rare. The new AASM scoring manual does not provide a scheme for grading severity of the PLM index. The ICSD-2 requires a PLM index of 15/hr in adults and 5/hr in children as criteria for the diagnosis of the PLMD (Table 12–4).1 TABLE 12–4 Periodic Leg Movement Disorder Diagnostic Criteria (ICSD-2)*

Monitoring of Limb Movements and Other Movements during Sleep

Limb Monitoring Techniques

Criteria for LMs and PLMs

LMs Associated with Respiratory Events Are Not Scored

Association of Arousals with PLM

Periodic Limb Movements in Sleep

Periodic Limb Movements in Wake

Suggested Immobilization Test

Clinical Significance of PLMS