Chapter 71 Movement Disorders

Movement Disorders and the Basal Ganglia

Basal Ganglia Anatomy

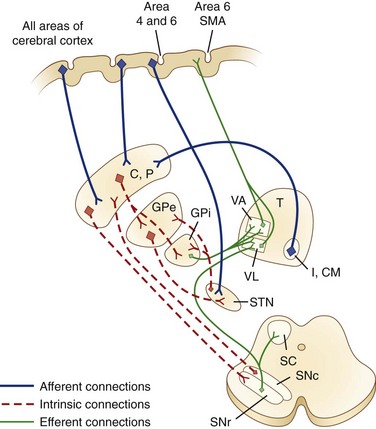

There is no clear consensus on which structures should be included in the basal ganglia. For the purposes of this discussion, we consider those structures in the striatopallidal circuits involved in modulation of the thalamocortical projection: the caudate nucleus, the putamen, the external segment of the GP (GPe), and the internal segment of the GP (GPi). In addition, the SNc, the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr), and the STN are included in the basal ganglia. The substantia nigra (SN), a melanin-containing (pigmented) nucleus, normally contains about 500,000 dopaminergic neurons. Several transcriptional regulators including Nurr1, Lmx1a, Lmx1b, Msx1, and Pitx3 are responsible for the development and maintenance of midbrain dopaminergic neurons (Le et al., 2009).

The caudate nucleus is a curved structure that traverses the deep hemisphere at the lateral edge of each lateral ventricle. Its diameter is largest at its head, tapering to a small tail. It is continuous with the putamen at the head and tail. The caudate and putamen together are called the striatum, and they form the major target for projections from the cerebral cortex and the SN. The putamen and the GP together form a wedge-shaped structure called the lenticular nucleus. The GP is divided into two parts, the GPe and the GPi. The GPi is structurally and functionally homologous with the SNr. The SNr and SNc extend the length of the midbrain ventral to the red nucleus and dorsal to the cerebral peduncles. The STN is a small lens-shaped structure at the border between the cerebrum and the brainstem. The basal ganglia and its relation to the thalamus and overlying cortex are illustrated in Fig. 71.1.

Functional Organization of the Basal Ganglia and Other Pathways

Afferent projections to the striatum arise from all areas of the cerebral cortex, the intralaminar nuclei of the thalamus, mesencephalic SN, and from the brainstem locus ceruleus and raphe nuclei. There is also a projection from the cerebral cortex to the STN. The major efferent projections are from the GPi and SNr to the thalamus and brainstem nuclei such as the pedunculopontine nucleus (PPN). The GPi and SNr project to ventral anterior and ventrolateral thalamic nuclei. The GPi also projects to the centromedian thalamic nuclei, and the SNr projects to the mediodorsal thalamic nuclei and superior colliculi. The ventral anterior and ventrolateral thalamic nuclei then project to the motor and premotor cortex. Throughout, these projections are somatotopically organized (Rodriguez-Oroz et al., 2009).

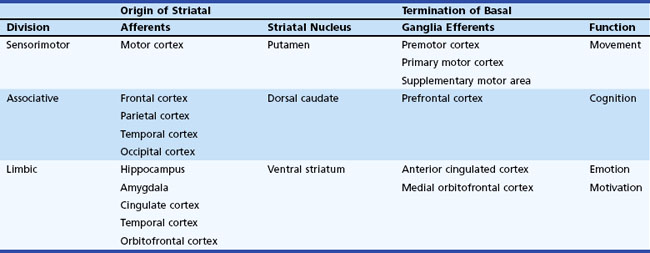

The basal ganglia has dense internuclear connections (see Fig. 71.1). Five parallel and separate closed circuits through the basal ganglia have been proposed. These are the motor, oculomotor, dorsolateral prefrontal, lateral orbitofrontal, and limbic loops (Rodriguez-Oroz et al., 2009). It is now generally agreed that these loops form three major divisions—sensorimotor, associative, and limbic—that are related to motor, cognitive, and emotional functions, respectively (Table 71.1). The functions of the sensorimotor striatum are subserved mainly by the putamen, which derives its afferent cortical inputs from both motor cortices. Sensorimotor pathways are somatotopically organized, and the pathway ultimately terminates in the premotor and primary motor cortices and the supplementary motor area. Cognitive functions are largely mediated by the associative striatum, particularly the dorsal caudate nucleus, which receives afferent input from the homolateral frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital cortices. Projections from this pathway ultimately terminate in the prefrontal cortex. The limbic striatum subserves emotional and motivational functions. Its input derives from the cingulate, temporal, and orbitofrontal cortices, the hippocampus, and the amygdala. It mainly comprises the ventral striatum, with ultimate projections to the anterior cingulate and medial orbitofrontal cortices (Rodriguez-Oroz et al., 2009). Whether these divisions are interconnected or organized in parallel remains a topic of debate.

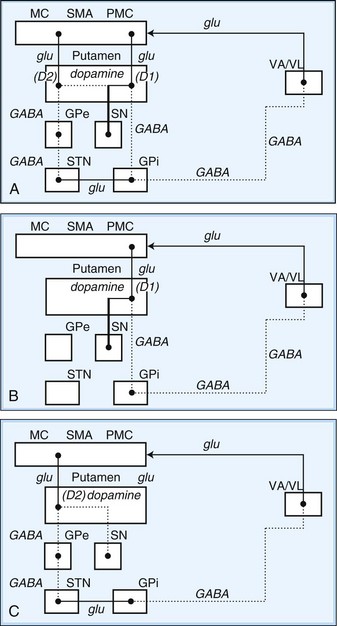

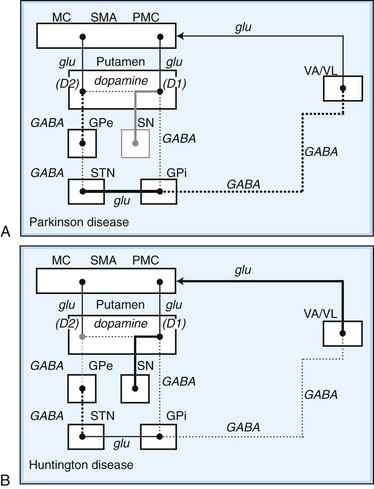

Within each basal ganglia circuit lies an additional level of complexity. Each circuit contains two pathways by which striatal activity is translated into pallidal output. These two pathways are named the direct and indirect pathways, depending on whether striatal outflow connects directly with the GPi or first traverses the GPe and STN before terminating in the GPi. The direct and indirect pathways have opposite effects on outflow neurons of the GPi and SNr (Fig. 71.2, A).

Fig. 71.2 Schematic drawing of internuclear connections of basal ganglia, including (A) direct and indirect pathways and (B) direct pathway. (See Fig. 71.3 for depiction of indirect pathway.) Excitatory pathways in solid lines, inhibitory pathways in dotted lines. D1, Dopamine D1 receptor; D2, dopamine D2 receptor; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; glu, glutamate; GPe, external segment of the globus pallidus; GPi, internal segment of the globus pallidus; MC, motor cortex; PMC, premotor cortex; SMA, supplementary motor area; SN, substantia nigra; STN, subthalamic nucleus; VA/VL, ventral anterior/ventrolateral thalamic nuclei.

In the motor direct pathway, excitatory neurons from the cerebral cortex synapse on putamenal neurons, which in turn send inhibitory projections to the GPi and its homolog, the SNr. The GPi/SNr sends an inhibitory outflow to the thalamus (see Fig. 71.2, B). Activity in the direct pathway disinhibits the thalamus, facilitating the excitatory thalamocortical pathway and enhancing activity in its target, the motor cortices. Thus, the direct pathway constitutes part of an excitatory cortical-cortical circuit that likely functions to maintain ongoing motor activity. In the indirect pathway, excitatory axons from the cerebral cortex synapse on putaminal neurons. These neurons send inhibitory projections to the GPe, and the GPe sends an inhibitory projection to the STN. The net effect of these projections is disinhibition of the STN. The STN in turn has an excitatory projection to the GPi (see Fig. 71.2, C). Activity in the indirect pathway thus excites the GPi/SNr, which in turn inhibits the thalamocortical pathway. Thus, the net effect of increased activity in the indirect pathway is cortical inhibition.

The striatum also receives robust afferent input from the SNc. This projection from the SNc, an important modifier of striatal activity, facilitates activity in the direct pathway, mediated via D1 dopamine receptors, and inhibits activity in the indirect pathway via D2 dopamine receptors (see Fig. 71.2, A).

Disorders of the basal ganglia result in prominent motor dysfunction, though not generally in frank weakness. The absence of direct primary or secondary sensory input and lack of a major descending pathway below the level of the brainstem suggest that the basal ganglia moderates rather than controls movement. The direct pathway is important in initiation and maintenance of movement, and the indirect pathway apparently plays a role in the suppression of extraneous movement. From this model of basal ganglia connectivity, hypotheses about the motor function of the basal ganglia have been proposed. One hypothesis is that the relative activities of the direct and indirect pathways serve to balance the facilitation and inhibition of the same population of thalamocortical neurons, thus controlling the scale of movement. A second hypothesis proposes that direct pathway-mediated facilitation and indirect pathway-mediated inhibition of different populations of thalamocortical neurons serve to focus movement in an organization reminiscent of center-surround inhibition. These hypotheses relate activity in the direct and indirect pathways mainly to rates of firing in the STN and GPi. Thus, death of neurons in the SNc, as in nigrostriatal degeneration associated with PD, decreases activity in the direct pathway and increases activity in the indirect pathway. These changes cause an increased rate of firing of subthalamic and GPi neurons, with excessive inhibition of thalamocortical pathways, and produce the behavioral manifestations of bradykinesia in PD (Fig. 71.3, A) (Hallett, 2011).

Fig. 71.3 Schematic drawing of functional activities in the direct and indirect pathways in Parkinson disease (PD) and Huntington disease (HD). A, In PD, reduced dopaminergic facilitation of direct pathway and inhibition of indirect pathway due to death of dopaminergic neurons causes increased firing and increased inhibition of thalamocortical pathways, producing bradykinesia. B, In HD, loss of striatal neurons leads to reduced activity in indirect pathway, causing reduced inhibition of thalamocortical pathways, with production of excessive or involuntary movements. (See Fig. 71.2 for explanations to abbreviations.)

On the other hand, predominant loss of indirect pathway neurons, as in HD, interferes with suppression of involuntary movements. Choreic involuntary movements are the usual result (see Fig. 71.3, B). Direct electrophysiological recordings of the STN and GP during stereotactic functional neurosurgical procedures confirm that the GPi and STN are overly active in patients with PD. The activity of these nuclei returns toward normal with effective pharmacotherapy, and chorea is associated with lower firing rates of neurons in these nuclei. Unfortunately, this model does not completely explain some important features of movement disorders. For example, bradykinesia and chorea coexist in HD and in patients with PD treated with levodopa (LD). Thalamic lesions that might be expected to worsen parkinsonism by reducing excitatory thalamocortical activity do not do so. Pallidal lesions that might be expected to worsen chorea by decreasing inhibition of thalamocortical pathways instead are dramatically effective at reducing chorea. The model is even more problematic when applied to dystonia. It has been suggested that in dystonia, there is overactivity of both the direct and indirect pathways. Yet, intraoperative recordings in dystonia have shown low rates and abnormal patterns of neuronal firing in the GPi. A simple change in firing rate of the STN or GPi is thus insufficient to explain the underlying physiology of dystonia. It is likely that disordered patterns and synchrony of pallidal firing, as well as changes in sensorimotor integration and the control of spinal and brainstem reflexes, are important. These factors are under investigation, but current models remain useful for understanding the rationale of pharmacological and ablative surgical procedures for certain movement disorders.

Biochemistry

The major neurotransmitters of the basal ganglia are outlined in Table 71.2 (see also Fig. 71.2). Most excitatory synapses of the basal ganglia and its connections—including those from the cerebral cortex to the striatum, the STN to the GPi, and the thalamocortical projections—use glutamate. Projections from the striatum to the GPe and GPi, from the GPe to the STN, and from the GPi to the thalamus are inhibitory and employ GABA. Medium spiny GABAergic neurons in the direct pathway co-localize substance P and dynorphin. GABAergic neurons in the indirect pathway co-localize enkephalin. Dopamine is the major neurotransmitter in the nigrostriatal dopamine system; it has excitatory or inhibitory actions depending on the properties of the stimulated receptor. Acetylcholine is found in large aspiny striatal interneurons and the PPN. Norepinephrine, important in the autonomic nervous system, is most concentrated in the lateral tegmentum and locus ceruleus. Serotonin is found in the dorsal raphe nucleus of the brainstem, hippocampus, cerebellum, and spinal cord.

Table 71.2 Pharmacology of the Basal Ganglia

| Pathway | Transmitter |

|---|---|

| STRIATAL AFFERENTS | |

| Cerebral cortex → striatum | Glutamate |

| Cerebral cortex → STN | Glutamate |

| Locus ceruleus → striatum | Norepinephrine |

| Locus ceruleus → SN | Norepinephrine |

| Raphe nuclei → striatum | Serotonin |

| Raphe nuclei → SN | Serotonin |

| Thalamus → striatum | Acetylcholine? |

| SNc → striatum | Glutamate? |

| Dopamine, cholecystokinin | |

| INTRINSIC CONNECTIONS | |

| Striatal interneurons | GABA, acetylcholine |

| Striatum → GPi | Somatostatin, neuropeptide Y |

| Striatum → SNr | Nitric acid, calretinin |

| Striatum → GPe | GABA, substance P |

| GPe → STN | GABA, dynorphin, substance P |

| STN → GPi, SNr, GPe | GABA, enkephalin, glutamate |

| STRIATAL EFFERENTS | |

| GPi → thalamus | GABA |

| SNr → thalamus | GABA |

GABA, γ-Aminobutyric acid; GPe, external segment of the globus pallidus; GPi, internal segment of the globus pallidus; SN, substantia nigra; SNc, substantia nigra pars compacta; SNr, substantia nigra pars reticulata; STN, subthalamic nucleus.

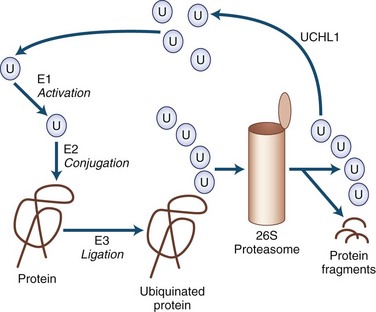

Mechanisms of Neurodegeneration

Many of the neurodegenerative movement disorders share the property of neuronal damage caused by the accumulation of aggregation-prone proteins that have toxic effects (Table 71.3). For a protein to function normally, it must be properly synthesized and folded into its normal three-dimensional structure. Nascent proteins are aided in folding by molecular chaperones. Proteins that are not properly folded, are otherwise damaged, or are beyond their useful lives are degraded by the ubiquitin-dependent proteasome protein degradation system (Gupta et al., 2008). In the ubiquitin-dependent proteasome system, proteins are first labeled for degradation by attachment of a polyubiquitin chain (Fig. 71.4). This three-step process involves activation, conjugation, and ligation steps catalyzed by three types of enzymes—E1, E2, and E3, respectively. Polyubiquinated protein enters the 26S proteasome, a cylindrical complex of peptidases. The end products of proteasome action are protein fragments and polyubiquitin. The polyubiquitin is then degraded and recycled to the cellular ubiquitin pool, a process requiring enzymatic action by ubiquitin carboxyterminal hydrolase 1.

Table 71.3 Toxic Proteins and Neurodegenerative Movement Disorders

| α-Synuclein | Tau | Polyglutamine Tract |

|---|---|---|

| Parkinson disease | Four-repeat tau | Huntington disease |

| Diffuse Lewy body disease | Progressive supranuclear palsy | Spinocerebellar ataxias |

| Multiple system atrophy | Corticobasal degeneration Frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism (chromosome 17) Parkinsonism dementia complex of Guam Postencephalitic parkinsonism | Dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy |

The cascade of pathogenic events linking abnormal protein aggregation to cell death is the subject of intense investigation. Although aggregates are the most striking physical change in surviving cells, the actual role of the aggregate remains a mystery. Indeed, many now believe that the formation of aggregates may be a protective mechanism sequestering the wayward protein from vulnerable cell processes. Misfolded proteins may produce the most mischief as they form protofibrils. A number of mechanisms have been described. In some cases, these are specifically related to the type of protein, but in many other cases, they are nonspecific mechanisms shared by all the misfolded protein diseases. Some potential mechanisms of neurodegeneration related to misfolded protein stress are listed in Box 71.1. The mutant protein may be unable to perform a vital function or may interfere with the function of the wild-type protein. Mutant protein, protofibrils, or aggregates might interfere with other proteins. Interference with transcription factors may be particularly important in this regard. Mutant proteins may activate caspases or in other ways activate the apoptotic cascade. They may interfere with intracellular transport or other vital processes. They may suppress activity of the proteasome, enhancing protein aggregation. They may interfere with mitochondrial function, making cells more vulnerable to excitotoxicity. In addition to the ubiquitin-proteasome system, lysosomes play an important role in degrading intracellular proteins by a process termed autophagy (Pan et al., 2008). When the function of the ubiquitin proteosome system is not sufficient to clear the accumulating cellular proteins, the autophagy lysosome pathway becomes the other important route for degradation of aggregated/misfolded proteins as well as sick or abnormal mitochondria. Accumulation of iron, increased oxidative stress, and microglial activation have also been thought to play important roles in the pathogenesis of various neurodegenerative disorders (Zhu et al., 2010).

Recent ultrastructural work has elucidated that many degenerative movement disorders can be linked to abnormal synthesis, folding, or degradation of specific proteins or protein families. Thus, a number of parkinsonian disorders are thought to result from neuronal accumulation of α-synuclein or tau proteins. Certain other disorders are linked to abnormalities in pathways involving proteins with expanded polyglutamine tracts (polyQ). Among these disorders, clinical and pathological differences depend on the distribution of protein aggregates or in the abnormal configuration they assume when they aggregate. The synucleinopathies include PD, Lewy body disease (LBD), and multiple system atrophy (MSA). The tauopathies include progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), corticobasal degeneration (CBD), familial frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism (FTDP), postencephalitic parkinsonism (PEP), posttraumatic parkinsonism, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)-PD of Guam. The polyQ disorders include HD, dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA), and many spinocerebellar ataxias (Ling et al., 2010; Williams and Lees, 2009).

Parkinsonian Syndromes

Parkinson Disease

Although the disease was described by others before him, James Parkinson is attributed with rendering the first cogent description of PD. In his monograph, The Shaking Palsy (1817), he identified the hallmark features of the illness through descriptions of cases observed in the streets of London as well as in his own patients. Over time, Parkinson disease or idiopathic PD has replaced the original term paralysis agitans as the name for the clinical syndrome of asymmetrical parkinsonism, usually with rest tremor, in association with the specific pathological findings of depigmentation of the SN due to loss of melanin-laden dopaminergic neurons containing eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions (Lewy bodies) (see Chapter 21). Dopamine deficiency in parkinsonian brain homogenates was described by Hornykiewicz in 1959, a discovery that ultimately led to highly effective pharmacotherapy with LD and direct-acting dopamine agonists (DAs). Recently, genetic forms of parkinsonism that are clinically indistinguishable from PD have been linked to mutations in several genes (Shulman et al., 2011). The discovery of different genetic forms of parkinsonism with variable penetrance has led to the current concept of PD as a syndrome with genetic and environmental etiologies, but overall, gene mutations are a rare cause of parkinsonism, particularly in those patients with late-onset disease (Gandhi and Wood, 2010).

Epidemiology and Clinical Features

In community-based series, PD accounted for more than 80% of all parkinsonism, with a prevalence of approximately 360 per 100,000 and an incidence of 18 per 100,000 per year (de Lau and Breteler, 2006). PD is an age-related disease, showing a gradual increase in prevalence beginning after age 50, with a steep increase in prevalence after age 60 (Driver et al., 2009). Disease before 30 years of age is rare and often suggests a hereditary form of parkinsonism. Prevalence rates in the United States are higher than those in Africa and China, but the role of race remains unclear. Within the United States, race-specific prevalence rates vary, with some studies suggesting a similar prevalence among whites and blacks. Unfortunately, blacks make up only a small fraction of most specialty clinic populations and thus are underrepresented in clinic-based studies and clinical trials. One study showed the world’s highest prevalence of PD may be among the Amish in the U.S. Northeast—nearly 6% of those 60 years of age or older, more than 3 times the prevalence for the rest of the country (Racette et al., 2009).

Typically, the onset and progression of PD are gradual. The most common presentation is with rest tremor in one hand, often associated with decreased arm swing and shoulder pain (Jankovic, 2008). Bradykinesia and rigidity are often detectable on the symptomatic side, and midline signs such as reduced facial expression or mild contralateral bradykinesia and rigidity may already be present. The presentation may be delayed if bradykinesia is the earliest symptom, particularly when the onset is on the nondominant side. The disorder usually remains asymmetrical throughout much of its course. With progression of the illness, generalized bradykinesia may cause difficulty arising from a chair or turning in bed. The gait and balance are progressively affected, and falls may occur. Sudden arrests in movement, also called freezing or motor blocks, soon follow, first with gait initiation, turning and traversing narrow or crowded environments, and then during walking. Bulbar functions deteriorate, impairing communication and nutrition. The tremor-dominant form of PD generally has a more favorable clinical course than PD dominated by gait disorder and postural instability (van Rooden et al., 2011).

The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) has been used to quantitate the various motor symptoms and signs of PD and to chart the course of the disease. This traditional scale, now known as the Movement Disorder Society (MDS)-UPDRS, has been revised to clarify some ambiguities in the original version and to capture early motor and also nonmotor symptoms associated with PD (www.movementdisorders.org). The Hoehn and Yahr stage, first described before effective dopaminergic treatment became available, outlines the milestones in progression of the illness from mild unilateral symptoms through the end-stage nonambulatory state. A modified version of the Hoehn and Yahr stage is commonly used in contemporary clinical trials (Table 71.4).

Table 71.4 Hoehn and Yahr Stage

| ORIGINAL SCALE | |

| Stage | Disease State |

| I | Unilateral involvement only, minimal or no functional impairment |

| II | Bilateral or midline involvement, without impairment of balance |

| III | First sign of impaired righting reflex, mild to moderate disability |

| IV | Fully developed, severely disabling disease; patient still able to walk and stand unassisted |

| V | Confinement to bed or wheelchair unless aided |

| MODIFIED SCALE | |

| Stage | Disease State |

| 0 | No signs of disease |

| 1 | Unilateral disease |

| 1.5 | Unilateral plus axial involvement |

| 2.0 | Bilateral disease without impairment of balance |

| 2.5 | Mild bilateral disease with recovery on pull test |

| 3.0 | Mild to moderate bilateral disease, some postural instability, physically independent |

| 4.0 | Severe disability, still able to walk or stand unassisted |

| 5.0 | Wheelchair bound or bedridden unless aided |

Nonmotor symptoms are increasingly recognized as a major cause of disability in PD and contribute prominently to declining quality of life, particularly in the more advanced stages of the disease (Lim et al., 2009). Autonomic symptoms include reduced gastrointestinal transit time with postprandial bloating and constipation, urinary frequency and urgency (sometimes with urge incontinence), impotence, disordered sweating, and orthostatic hypotension (Mostile and Jankovic, 2009). Cognitive and behavioral changes are also very common. Attention and concentration wane. Executive dysfunction with diminished working memory, planning, and organization is common. Global dementia occurs in approximately 30% of patients, increasing in frequency with the age of the patient. Those with prominent early executive dysfunction and more severe motor signs seem particularly at risk. Anxiety, depression, and other mood disorders are common in PD. Sleep disturbance is nearly universal in PD and is multifactorial.

Disordered sleep onset and maintenance lead to fragmentation of nocturnal sleep. A variety of motor movements including restless legs and periodic leg movements of sleep may be seen, and many patients have rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder (RBD) with active motor movements during REM sleep (Postuma et al., 2010). Some patients have sleep apnea. Vivid dreams and nightmares are very common, particularly in treated patients. Sleep disorders in PD variably relate to the pathological changes of the disease itself, arousals due to immobility, comorbid primary sleep disorders, and side effects of antiparkinsonian medications. Many patients with PD are excessively sleepy during the day, sometimes with serious consequences such as unintended sleep episodes while driving. In most cases, this excessive daytime drowsiness is related to dopaminergic drugs. Fatigue is a common and complex symptom of PD. The differentiation of fatigue from excessive daytime sleepiness, depression, apathy, and other conditions can be difficult, and there is not yet a useful body of literature on its assessment and treatment.

Clinicopathological studies have found that the clinical syndrome that best reflects the typical pathological changes of PD, in the absence of other diagnoses known to cause parkinsonism, is an asymmetrical illness with rest tremor along with rigidity or bradykinesia and marked improvement with LD. Misdiagnosed cases generally are found to have MSA, PSP, or subcortical vascular disease. When making the diagnosis of early PD, the clinician should be aware of a number of red flags (Box 71.2) (see Chapter 21). Cognitive impairment within the first year should raise the possibility of Alzheimer disease (AD), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), CBD, PSP, or FTDP. Symmetrical or prominent midline or bulbar signs suggest MSA or PSP. Early gait disorder with falls points to the diagnosis of PSP or to subcortical vascular disease. Dependence on a wheelchair within 5 years of onset is suggestive of PSP or MSA. Early orthostatic hypotension or incontinence points to the autonomic dysfunction of MSA. Severe sleep apnea, inspiratory stridor, or involuntary sighing also suggests MSA. Apraxia, alien limb, or cortical sensory loss is typically seen in CBD.

Box 71.2 “Red Flags” Suggesting a Diagnosis Other than Parkinson Disease

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree