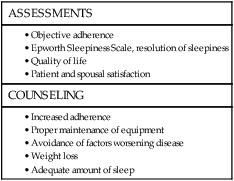

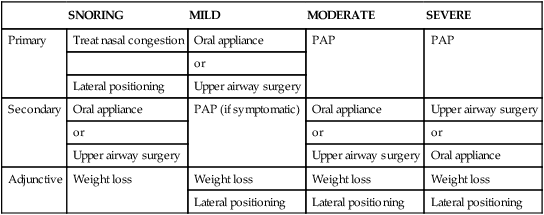

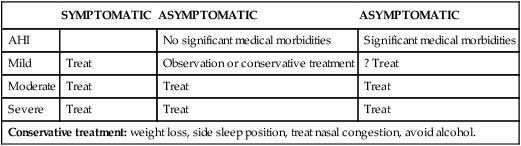

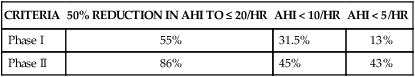

• The choice of treatment for OSA depends on OSA severity, symptoms, co-morbid medical conditions, patient preference, and sometimes economic issues. • Treatment options for snoring included the side sleep position, treatment of nasal congestion, weight loss (adjunctive), an OA, or upper airway surgery. • Treatment options for mild OSA include the side sleep position, treatment of nasal congestion, weight loss (adjunctive), an OA, or upper airway surgery. If the patient is symptomatic, PAP treatment can also be effective if the patient is motivated. • Treatment options for moderate OSA include PAP (treatment of choice), an OA, or upper airway surgery. Weight loss or the side sleep position is adjunctive. • Treatment options for severe OSA include PAP (treatment of choice), upper airway surgery such as the MMA (if anatomy is favorable and the patient is a good surgical candidate), or an OA (third option). • Mild to moderate weight loss can reduce the AHI, but weight loss takes time and is considered adjunctive therapy. • Bariatric surgery resulting in weight loss can reduce the AHI. However, a substantial fraction of patients with presurgery OSA continue to need treatment after weight loss stabilizes. In some patients, the required level of CPAP is lower. OSA can return even in the absence of weight gain. • Positional therapy can be effective in patients with positional OSA, but long-term studies of effectiveness are lacking. Sleep in the lateral position or with the head elevated can reduce the level of CPAP required to keep the airway open. • Modafinil (armodafinil) is indicated for treatment of residual excessive daytime sleepiness in patients with OSA on effective CPAP treatment (good adherence and effective pressure) when other sleep disorders have been ruled out. Continued monitoring of PAP adherence is essential. • The AASM practice parameters state that supplemental oxygen treatment is not indicated for treatment of OSA. However, individual patients may benefit if they do not tolerate or do refuse more effective treatment. Oxygen treatment can increase event duration. Significant worsening of nocturnal and daytime hypercapnia can occur in some patients with the use of supplemental oxygen. The severity of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), co-morbid conditions, patient preference, and financial considerations may all factor into the choice of treatment modality1–6 (Table 18–1). The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) has published practice parameters for medical,3 surgical,4 oral appliance (OA),5 and positive airway pressure (PAP)6 treatments for sleep apnea. Medical treatments for OSA are discussed in this chapter. Treatment of OSA with PAP is discussed in detail in Chapter 19 and OA and surgical treatment of OSA are covered in Chapter 20. Although treatment options for OSA are usually classified by apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) severity, symptoms do not correlate well with the AHI. Therefore, the goal should be “treat the patient, not the AHI.” Another concept to consider is efficacy versus effectiveness. For example, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is very efficacious, often lowering the AHI to less than 5 to 10/hr. However, the effectiveness of CPAP depends on adherence to treatment. If CPAP reduces the AHI from 55 to 5/hr but is used only 50% of the time during sleep, the effective average AHI is really 30/hr. The ideal OSA treatment goals include normalization of the AHI and nocturnal oxygenation and resolution of symptoms associated with OSA. TABLE 18–1 Treatment Alternatives for Obstructive Sleep Apnea (Adults)4–6 Whereas most clinicians recommend treatment of patients with an AHI of 15/hr or greater even if not symptomatic, treatment of mild OSA remains controversial.7,8 However, there can be night-to-night variability in the AHI and even patients with mild OSA can be symptomatic. In the Sleep Heart Health Study, 28% of individuals with an AHI greater than 5 but less than 15 had subjective sleepiness (Epworth Sleepiness Scale [ESS] ≥ 11).9 The Wisconsin cohort study found a 2.03 greater risk of incident hypertension in patients with an AHI in the range of 5 to 14.9 compared with individuals without sleep apnea (AHI = 0/hr).10 The fact that even mild OSA could have adverse consequences is supported by a recent finding that snoring alone can cause carotid atherosclerosis.11 Effective treatment of patients with mild OSA can improve symptoms. A meta-analysis of treatment studies of mild to moderate OSA found that CPAP significantly reduced subjective sleepiness (the ESS decreased by 1.2 points) and improved objective wakefulness (measure of wakefulness test [MWT] sleep latency increased by 2.1 min).12 Conversely, Barbé and coworkers13 found no benefit to CPAP treatment in a group of nonsleepy patients with mild to moderate OSA. Whereas suboptimal CPAP adherence has often been reported in studies of patients with mild OSA, several studies found 40% to 60% of patients had greater than 4 hours use for 70% of nights.7 At least four treatment considerations affect the decision to treat a patient with OSA. The first category is the severity of OSA as based on the AHI or extent of arterial oxygen desaturation. The second consideration is presence or absence of symptoms. Symptomatic OSA should always be treated but the choice of treatment may vary, as noted later. The third consideration is the impact of OSA on the sleep of the patient’s bed partner. Loud snoring and apnea may cause marital discord and impair the sleep of the patient’s bed partner.14 In some cases, sleeping in separate bedrooms is the most acceptable solution. However, if this is not acceptable, treatment of the OSA patient can significantly improve the sleep of the bed partner.14 The fourth category is the increased risk of adverse cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with untreated sleep apnea. The evidence that untreated sleep apnea is associated with an increased risk of death or adverse cardiovascular event is strongest for severe OSA (AHI > 30/hr) and in men who are 40 to 70 years of age.15,16 The evidence is less clear for moderate OSA and for women. However, the presence of certain co-morbid conditions such as coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, arrhythmias, or congestive heart failure may increase the risk even for milder degrees of sleep apnea.17 Given that PAP treatment is safe and effective, treatment of patients with moderate OSA is recommended even if patients are asymptomatic. Table 18–2 illustrates an approach to the decision of whom to treat. Symptomatic patients with all severities of OSA should be treated with an effective therapy. Asymptomatic patients with moderate to severe OSA should also be treated. For asymptomatic patients with mild OSA and no obvious significant medical co-morbidities, either observation or conservative treatment (weight loss/lateral positioning) is reasonable. The patient should be informed that even mild OSA carries some increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity. For asymptomatic patients with mild OSA and significant medical co-morbidities, treatment decisions should be individualized based on the patient’s motivation to undergo treatment. Treatment success in asymptomatic patients with mild OSA requires them to be motivated. TABLE 18–2 Treatment options for snoring, mild, moderate, and severe OSA are discussed in detail in the following sections. The options by category of AHI severity are listed in Table 18–1. For snoring patients for whom treatment is felt necessary, a number of therapies are available including weight loss, medical treatment of nasal congestion, the side (lateral) sleeping position, and avoidance of alcohol. If medical treatment does not improve nasal congestion, nasal surgery may address this problem, although improvement in snoring is variable.18,19 OAs or upper airway surgery involving the palate may improve snoring in many patients.6,20–25 The surgical procedures commonly used for snoring include laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty (LAUP), radiofrequency palatoplasty, and uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP).21–23 The Pillar procedure involves insertion of Teflon strips into the palate. The success of this procedure is variable, and sometimes additional strip insertion is needed.22 A controlled study comparing the Pillar procedure with a sham surgery found modest improvement in snoring without a significant improvement in the AHI.23 The LAUP procedure is not recommended for treatment of sleep apnea.24 The recently published American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) practice parameters for surgical treatment of OSA4 state “palatal implants may be effective in some patients with mild OSA who cannot tolerate or are unwilling to adhere to PAP therapy, or in whom oral appliances have been considered and found ineffective or undesirable.” However, the evidence to support this recommendation is not very convincing and it is not clear that palatal implants are any more effective for sleep apnea than the LAUP procedure. For mild OSA, one may again begin with conservative measures in (especially in asymptomatic patients) including treatment of nasal congestion, weight loss, or the lateral sleeping position. Weight loss takes time, and if the patient is symptomatic, weight loss should be considered a secondary (adjunctive) treatment.3 Both OAs and upper airway surgery are reasonably effective for mild OSA.4,5,20–25 PAP is very efficacious at reducing the AHI,1,2,6 but acceptance and adherence are typically lower than with more severe OSA. PAP treatment is not indicated in mild OSA if patients are asymptomatic and have no co-morbid cardiovascular disorders.2 In symptomatic patients with mild OSA, some patients may prefer a trial of PAP rather than an OA or upper airway surgery. PAP treatment is safe and it is often difficult to predict who will benefit. If the patient is motivated to try PAP, the dictum “when in doubt, pressurize the snout” should be considered.26 If PAP is not an acceptable option, the choice between upper airway surgery or an OA to treat mild OSA often depends upon financial considerations and patient preference. At the present time, many insurance plans will not pay for OA treatment for sleep apnea. However, OA treatment is now reimbursed by Medicare if certain conditions are met (see Chapter 20). Reimbursement by insurance or Medicare requires that patients with mild OSA be symptomatic. For moderate OSA, the treatment of choice is some form of PAP.1,2,5 For moderate OSA, OA treatment and upper airway surgery are less reliable than PAP at reducing the AHI to less than 10/hr. However, they may be more acceptable to some patients and more “effective” if patients do not have reasonable PAP adherence.1,5,20,21 Upper airway surgery obviates the need for treatment adherence. Treatment adherence is still an issue with OA treatment, and currently, there is no method to objectively monitor adherence to OA treatment. A recent AASM task force review concluded that OA was about 50% effective for moderate OSA (defined as a treatment AHI < 10/hr).20 A meta-analysis of surgery in OSA patients concluded that palatal surgery with or without genioglossus advancement was approximately 30% effective, using a strict outcome measure of reduction in the AHI to less than 10/hr.25 Therefore, for moderate OSA, PAP is the most reliably efficacious treatment. It is very effective if adherence is adequate. Most clinicians would recommend a trial of PAP therapy for patients with moderate OSA. If this treatment is not acceptable or the patient is not adherent to PAP treatment, upper airway surgery or an OA would be alternatives. The AASM practice parameters for the surgical treatment of OSA4 state “Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) as a sole procedure, with or without tonsillectomy, does not reliably normalize the AHI when treating moderate to severe OSA. Therefore, patients with severe OSA should initially be offered PAP therapy, while those with moderate OSA should initially be offered either PAP therapy or oral appliances.” However, economics or patient preference may favor surgery over OA treatment in some settings. If patients with moderate OSA pursue weight loss with bariatric surgery, an effective immediate treatment for OSA is indicated because weight loss takes time. For severe OSA, PAP is the treatment of choice because of its effectiveness and safety.1,2,6 Unfortunately, acceptance and adherence can be as low as 50% depending on the definition of adherence. The maxillary mandibular advancement (MMA) operation can result in acceptable residual AHIs in many patients with severe OSA.4,21 A recent meta-analysis found that up to 90% of patients undergoing MMA had improvement in symptoms and a postoperative AHI less than 20/hr (only 30% had a reduction in AHI to < 10/hr)25 (Table 18–3). Some surgeons perform MMA only after other surgical procedures have failed. However, in very obese patients with retrognathia, performing MMA as the first surgical procedure is recommended by some clinicians. Tracheostomy is effective when life-threatening OSA and respiratory failure are present and the patient is not compliant with PAP treatment.4 Surgical treatment options are discussed in more detail in Chapter 20. If neither PAP nor surgery is an acceptable treatment option, some patients with severe OSA will have significant improvement in the AHI with OA treatment. Although the AHI is usually not reduced below 10/hr, one could argue that a drop from 80/hr to 20/hr is worthwhile, especially if there is symptomatic improvement and an improvement in oxygenation. TABLE 18–3 Meta-Analysis Results for Upper Airway Surgery (% Success Rates) AHI = apnea-hypopnea index; MMA = maxillary-mandibular advancement. From Elshaug AG, Moss JR, Southcott A, et al: Redefining success in airway surgery for obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis and synthesis of the evidence. Sleep 2007;30:461–467. Following polysomnography (PSG) or portable monitoring (home sleep testing, limited-channel sleep testing), the physician ordering the study should discuss the findings and the consequences of untreated sleep apnea with the patient (Table 18–4).1 The factors that can exacerbate OSA, including weight gain, insufficient sleep, medications, and alcohol consumption, should also be addressed. The available treatment options and the pros and cons of each option should be discussed. Whereas most patients look to the physician for ultimate recommendations, involving the patient and spouse in decision making is essential to improve treatment outcomes. Drowsy driving counseling should be performed and documented. Many patients have co-morbid conditions such as depression, insomnia, restless legs syndrome (RLS), or chronic pain that will make compliance with PAP or other treatments more difficult. These should be evaluated and treated. TABLE 18–4 Patient Education and Co-morbid Disorders OSA = obstructive sleep apnea; RLS = restless legs syndrome. Following treatment initiation, careful follow-up is essential because OSA is a chronic disease. Table 18–5 lists some outcome assessments that were suggested in recent clinical guidelines.1 A follow-up sleep study is recommended after upper airway surgery for moderate to severe OSA1,4,5,27 and after final adjustment of an OA as treatment for all severities of OSA.5 Practice parameters have been published for use of “medical” treatments for OSA3 including weight loss, positioning, medications, oxygen, and alerting agents (Table 18–6). Documentation of the effectiveness of treatment and continued monitoring of adherence are important. TABLE 18–6 American Academy of Sleep Medicine Practice Parameter Recommendations for Medical Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea • Protriptyline, SSRIs, aminophylline, estrogen preparations with or without progesterone, and short-acting decongestants.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea Treatment Overview and Medical Treatments

Introduction

SNORING

MILD

MODERATE

SEVERE

Primary

Treat nasal congestion

Oral appliance

PAP

PAP

or

Lateral positioning

Upper airway surgery

Secondary

Oral appliance

PAP (if symptomatic)

Oral appliance

Upper airway surgery

or

or

or

Upper airway surgery

Upper airway surgery

Oral appliance

Adjunctive

Weight loss

Weight loss

Weight loss

Weight loss

Lateral positioning

Lateral positioning

Lateral positioning

Should Mild OSA Patients Be Treated?

Whom to Treat

SYMPTOMATIC

ASYMPTOMATIC

ASYMPTOMATIC

AHI

No significant medical morbidities

Significant medical morbidities

Mild

Treat

Observation or conservative treatment

? Treat

Moderate

Treat

Treat

Treat

Severe

Treat

Treat

Treat

Conservative treatment: weight loss, side sleep position, treat nasal congestion, avoid alcohol.

Treatment Selection

Snoring

Mild OSA

Moderate OSA

Severe OSA

CRITERIA

50% REDUCTION IN AHI TO ≤ 20/HR

AHI < 10/HR

AHI < 5/HR

Phase I

55%

31.5%

13%

Phase II

86%

45%

43%

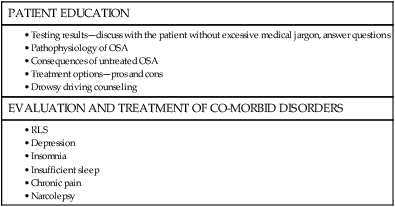

Patient Education Before Treatment

PATIENT EDUCATION

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT OF CO-MORBID DISORDERS

Follow-Up and Outcomes Assessment

Medical Treatments for OSA

WEIGHT REDUCTION

POSITIONAL THERAPIES

OXYGEN SUPPLEMENTATION

NASAL CORTICOSTEROIDS

MODAFINIL, ARMODAFINIL

OTHER TREATMENTS (NOT RECOMMENDED)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access